Encounters with the Avant-Garde: Four Case Studies in the Reception History of Contemporary Flute Works (1971 to Present)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roger Smalley: a Case-Study of Post -50S Western Music

Research Report: Roger Smalley: A Case-Study of Post -50s Western Music Christopher Mark When I gave a seminar on Roger Smalley's Concerto for Piano and Orchestra at the University of Melbourne in April 1992, a number of people asked me 'Why Smalley?' I'm still not sure quite how to take this. The general reaction to the work, and to my presentation, was positive (at least, that was the impression I gained), and I don't think the question was of the 'why are you spending your time on this drivel' variety. I think it arose because very few people in the audience of staff and graduate students had heard the work-which is remarkable given its high prominence as winner of the Paris Rostrum, its relatively heathy number of broadcasts and its wide availability on an Australian Music Centre CD (Vox Australis, VAST 003-21988)- and were puzzled as to how I had heard of him. My answer, which I suspect they may have found naive, was simply that I had known of Smalley when he was still in the LJK, and had heard a few of the early Australian pieces (such as the Symphony and the Konzertstiidc for solo violin and orchestra) when they were broadcast on BBC radio. I had liked the music and wanted to get to know it better. I still hold that this is the most important impulse for the academic study of music. It drives all my research. And with Smalley I can be very precise about what drew me to his scores: the expressive range of both the Concerto and the other work on the CD I have mentioned, the Symphony, and the sense that every note has been fully considered. -

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

Claire Chase: Cerchio Tagliato Dei Suoni and Density

Claire Chase: Cerchio Tagliato dei Suoni and Density Sat, Apr 4 PART ONE Grazie Migranti! Royce Hall Marcos Balter (b. 1974): Alone (2014), 4pm for flute and wine glasses and ambient The Center would like to thank all the flute enthusiasts percussion who have joined us this week to bring Cutting the Circle WEST COAST PREMIERE of Sounds to vibrant life, both here today and earlier in rehearsals at the Hammer Museum. It has been a true Salvatore Sciarrino (b. 1947): Il cerchio migration, with performers traveling from San Diego and tagliato dei suoni (1977), for four flute RUNNING TIME: Santa Barbara and participants joining in where and when soloists and one hundred migrating flutists Approximately two and a WEST COAST PREMIERE they can. We were able to capture most of the names of the half hours; migrating flutists you will see here tonight in time for this One intermission Claire Chase Flutes printing. Each person on site today has our deep gratitude Michael Matsuno Flute for their generous contribution of time and energy to this Erin McKibben Flute unique project. Members of the migranti include: Christine Tavolacci Flute Levy Lorenzo Sound Engineer Robert Gonyo Production Aika Dan, Aileen Garcia, Ann Carlson, Amanda Vader, Amy Two, Arlette Flores, Barbara Gasior, Beth Ross CAP UCLA SPONSOR: Manager Supported in part by Intermission Buckley, Breanna Ohler, Catherine Marshall, Carlos The Andrew W. Mellon Cherish Zinn, Christine Buckley, Claire Hafteck, Daniel Foundation. PART TWO Valle, Dickson McMurray, Diego Monico, Elena Yarritu, Additional support Eloisa Perez, Emily Flores, Evan Caplinger, Eve Newton, Steve Reich (b. -

Teaching Electronic Music – Journeys Through a Changing Landscape

Revista Vórtex | Vortex Music Journal | ISSN 2317–9937 | http://vortex.unespar.edu.br/ D.O.I.: https://doi.org/10.33871/23179937.2020.8.1.12 Teaching electronic music – journeys through a changing landscape Simon Emmerson De Montfort University | United Kingdom Abstract: In this essay, electronic music composer Simon Emmerson examines the development of electronic music in the UK through his own experience as composer and teacher. Based on his lifetime experiences, Emmerson talks about the changing landscape of teaching electronic music composition: ‘learning by doing’ as a fundamental approach for a composer to find their own expressive voice; the importance of past technologies, such as analogue equipment and synthesizers; the current tendencies of what he calls the ‘age of the home studio’; the awareness of sonic perception, as opposed to the danger of visual distraction; questions of terminology in electronic music and the shift to the digital domain in studios; among other things. [note by editor]. Keywords: electronic music in UK, contemporary music, teaching composition today. Received on: 29/02/2020. Approved on: 05/03/2020. Available online on: 09/03/2020. Editor: Felipe de Almeida Ribeiro. EMMERSON, Simon. Teaching electronic music – journeys throuGh a chanGinG landscape. Revista Vórtex, Curitiba, v.8, n.1, p. 1-8, 2020. arly learning. The remark of Arnold Schoenberg (in the 1911 Preface to his Theory of Harmony) – “This book I have learned from my pupils” – is true for me, too. Teaching is E learning – without my students I would not keep up nearly so well with important changes in approaches to music making, and it would be more difficult to develop new ideas and skills. -

Bibliographie Stockhausen 1952-2013 Engl

Stockhausen-Bibliography 1952-2013 [June 2013] The following bibliography alphabetically lists the authors who have written secondary literature about Karlheinz Stockhausen’s oeuvre: monographs, articles in books, periodicals and dictionaries, comprehensive works in which Stockhausen’s oeuvre is examined in detail. Reviews, contributions to concert programmes and publications in daily and weekly newspapers are only mentioned if they are considered to have reference value. Stockhausen’s own texts are not included, and conversations and interviews are only partly listed. Several works by the same author are listed consecutively in chronological order. When the name of the author was not available, the titel was listed alphabetically. This list includes the bibliographies that were published in Texte zur Musik, Vol. 6 (compiled by Chr. von Blumröder and H. Henck) and Vol. 10 (Chr. von Blumröder, R. Sengstock, D. Schwerdtfeger), and was supplemented and up-dated until 2013 (M. Luckas, I. Misch). Abkürzungen und Siglen / Abbreviations and Sigla AfMw. Archiv für Musikwissenschaft / Archive for Musicology Aufl. Auflage / printing Ausg. Ausgabe / edition Bd., Bde Band, Bände / volume, volumes Beitr. Beitrag / contribution BzAfMw. Beihefte zum Archiv für Musikwissenschaft / Supplementary booklets for the Archive for Musicology ders., dies. derselbe, dieselbe / the same DMT Dansk musiktidsskrift dt. deutsch / German eng. englisch / English erw. erweitert / supplemented Ffm. Frankfurt am Main / Frankfurt FP Feedback Papers frz. französisch / French H. Heft / booklet, issue Hbg Hamburg hg. herausgegeben / edited HmT Handwörterbuch der musikalischen Terminologie, hg. v. H. H. Eggebrecht, Wiesbaden 1972–1983, Stuttgart 1984–2006 / Hand Dictionary of Musical Terminology Ins. Institut / Institute jap. japanisch / Japanese Ldn London 1 ML Music and Letters MR The Music Review MT The Musical Times MuB Musik und Bildung Mw. -

Rmc193chiprograml5.Pdf

SATURDAY APRIL 29, 2017 | 7:30 PM | ROCKEFELLER CHAPEL A TRIPTYCH: Earth, Moon, Peace Works of Augusta Read Thomas Played by Spektral Quartet and Third Coast Percussion ROCKEFELLER CHAPEL | UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OF UNIVERSITY 2 PROGRAM The program is performed without intermission, although there will be brief pauses for resetting the stage. You are warmly invited to a wine and cheese reception here in the Chapel after the concert, with refreshments served from the west transept. You will also find CDs on sale. RAINBOW BRIDGE TO PARADISE SELENE Moon Chariot Rituals 2016 2015 3 Russell Rolen CELLO Spektral Quartet Third Coast Percussion and CHI CHI | A TRIPTYCH: EARTH, MOON, PEACE CHI for string quartet RESOUNDING EARTH 2017 World première 2012 I CHI vital life force I INVOCATION pulse radiance II AURA atmospheres, colors, vibrations II PRAYER star dust orbits III MERIDIANS zeniths III MANTRA ceremonial time shapes IV CHAKRAS center of spiritual power in the body IV REVERIE CARILLON crystal lattice Spektral Quartet Third Coast Percussion Clara Lyon VIOLIN David Skidmore Maeve Feinberg VIOLIN Peter Martin Doyle Armbrust VIOLA Robert Dillon Russell Rolen CELLO Sean Connors ABOUT THIS CONCERT Like most works of art, tonight’s concert came into Enter Spektral Quartet (or re-enter, for this being through the confluence of flashes of desire, conversation also had begun, allegro con spirito, some snippets of conversation, and the sudden alignment of eons before). On March 7, 2015, the cosmic lights went energies sparked by the commissioning of a new work. green and we knew we had a program: Selene, to be The flash of desire came just over three years ago. -

Programmheft Und Die Konzerteinführung Gehören Zu Den Ergebnissen Dieser Arbeit

© Stockhausen-Archiv Ensemble Earquake Oboe..................................Margarita Souka Violoncello.........................Claudia Cecchinato Klarinette...........................Man-Chi Chan Fagott................................Berenike Mosler Violine.................................Anna Teigelack Tuba...................................Sandro Hartung Flöte...................................Samantha Arbogast Posaune.............................Daniil Gorokhov (a.G.) Viola...................................Tom Congdon Trompete...........................Jonas Heinzelmann Kontrabass.........................Marian Kushniryk Horn...................................Lukas Kuhn Schlagzeug........................Nadine Baert Klangregie.........................Selim M’rad Caspar Ernst Ernst-Lukas Kuhlmann Tutor...................................Orlando Boeck Musikalische Leitung.........Kathinka Pasveer Gesamtleitung...................Merve Kazokoğlu Was bedeutete „Neue Musik“ für Karlheinz Stockhausen? Ganz und gar optimistisch, neugierig und kosmopolitisch scheint Stockhausens Musik – und nicht mehr in den engen Grenzen europä- ischer Musikästhetik verstehbar. Zwar war Stockhausen selbst ein Teil der westdeutschen musikalischen Avantgarde nach 1945 und prägte daher zahlreiche Neuerungen der hiesigen damaligen Musikgeschich- te, – hier sind serielle Techniken ebenso wie die künstliche Tonerzeu- gung mit Studiotechnik erwähnenswert, – endgültig verpflichtet bliebt er jedoch keinem der dort erprobten Ansätze und verband die gewon- nenen Anregungen -

Eric Chasalow/Over the Edge New World Records 80440 in Art, One

Eric Chasalow/Over the Edge New World Records 80440 In art, one and one at times make three. In art for the ear, and particularly with acoustic in combination with electronically-created sounds, the listener tends to hear rather more than a lockstep summation of parts. And it's perhaps this phantom dimension that most intrigues the listener. Again perhaps, as in a difficult love affair, a resonance arises from the antipodal aspects of seeming incompatibility and obviously compelling attraction. One is therefore given to approach music so conceived as forever newly plowed ground. Odd, then, in terms of expectation, that the first electro-acoustic compositions incorporating magnetic tape appeared (as I write) just over forty years ago: New Grove cites Bruno Maderna's aptly titled Musica su due dimensione I, for flute and tape, and Edgard Varese's Deserts of 1950-54, for orchestra and tape, as among the earliest examples. Earlier still, in 1939, before the advent of magnetic tape, John Cage composed his Imaginary Landscape No. 1, for piano, Chinese cymbal, and two variable-speed turntables. Significant music marks the way as milestones, with regard particularly to this CD. Karlheinz Stockhausen's 1959-60 version of Kontakte, for tape, piano, and percussion; Milton Babbitt's 1963-64 Philomel, for soprano, recorded soprano, and synthesized tape; Babbitt's 1974 Reflections, for piano and synthesized tape; Roger Reynolds's Transfigured Wind IV from 1985, for flute, computer, and tape; and Mario Davidovsky's ten Synchronisms, for a variety of solo instruments, ensemble combinations, and tape. Eric Chasalow's choice to study with Davidovsky is significant. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

Prospective Encounters

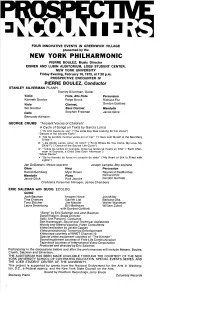

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews -

Sfkieherd Sc~Ol Ofmusic

GUEST ARTIST RECITAL JEFFREY JACOB, Piano Thursday, September 18, 2008 8:00 p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall sfkieherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic PROGRAM Makrokosmos II George Crumb Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac (b.1929) (for amplified piano) 1. Morning Music (Genesis II) 2. The Mystic Chord 3. Rain-Death Variations 4. Twin Suns (Doppelganger aus der Ewigkeit) 5. Ghost-Nocturne: For the Druids of Stonehenge 6. Gargoyles 7. Tora I Tora I Tora I ( Cadenza Apocalittica) 8. A Prophecy of Nostradamus 9. Cosmic Wind 10. Voices from "Corona Borealis" 11. Litany of the Galactic Bells 12. Agnus Dei The reverberative acoustics of Duncan Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use ofrecording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHY Described by the Warsaw Music Journal as "unquestionably one of the greatest performers of 20th-century music," and the New York Times as "an artist ofintense concentration and conviction," Jeffrey Jacob re ceived his education from the Juilliard School (Master of Music) and the Peabody Conservatory (Doctor ofMusical Arts) and counts as his prin cipal teachers Mieczyslaw Munz, Carlo Zecchi, and Leon Fleisher. Since his debut with the London Philharmonic in Royal Festival Hall, he has appeared as piano soloist with over twenty orchestras internationally including the Moscow, St. Petersburg, Seattle, Portland, Indianapolis, Charleston, Silo Paulo and Brazilian National Symphonies, and the Si lesian, Moravian , North Czech, and Royal Queenstown Philharmonics. A noted proponent ofcontemporary music, he has performed the world premieres of works written for him by George Crumb, Gunther Schuller, Vincent Persichetti, Samuel Adler, Francis Routh, and many others. -

A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a Study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and His Effect on the Trumpet

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet Michael Joseph Berthelot Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Berthelot, Michael Joseph, "A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3187. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SYMPHONIC POEM ON DANTE’S INFERNO AND A STUDY ON KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN AND HIS EFFECT ON THE TRUMPET A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Michael J Berthelot B.M., Louisiana State University, 2000 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 December 2008 Jackie ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dinos Constantinides most of all, because it was his constant support that made this dissertation possible. His patience in guiding me through this entire process was remarkable. It was Dr. Constantinides that taught great things to me about composition, music, and life.