Urban Conflagrations in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resource Advisor Guide

A publication of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group Resource Advisor Guide PMS 313 AUGUST 2017 Resource Advisor Guide August 2017 PMS 313 The Resource Advisor Guide establishes NWCG standards for Resource Advisors to enable interagency consistency among Resource Advisors, who provide professional knowledge and expertise toward the protection of natural, cultural, and other resources on wildland fires and all-hazard incidents. The guide provides detailed information on decision-making, authorities, safety, preparedness, and rehabilitation concerns for Resource Advisors as well as considerations for interacting with all levels of incident management. Additionally, the guide standardizes the forms, plans, and systems used by Resource Advisors for all land management agencies. The National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) provides national leadership to enable interoperable wildland fire operations among federal, state, tribal, territorial, and local partners. NWCG operations standards are interagency by design; they are developed with the intent of universal adoption by the member agencies. However, the decision to adopt and utilize them is made independently by the individual member agencies and communicated through their respective directives systems. Table of Contents Section One: Resource Advisor Defined ...................................................................................................................1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................1 -

The Art of Reading Smoke for Rapid Decision Making

The Art of Reading Smoke for Rapid Decision Making Dave Dodson teaches the art of reading smoke. This is an important skill since fighting fires in the year 2006 and beyond will be unlike the fires we fought in the 1900’s. Composites, lightweight construction, engineered structures, and unusual fuels will cause hostile fires to burn hotter, faster, and less predictable. Concept #1: “Smoke” is FUEL! Firefighters use the term “smoke” when addressing the solids, aerosols, and gases being produced by the hostile fire. Soot, dust, and fibers make up the solids. Aerosols are suspended liquids such as water, trace acids, and hydrocarbons (oil). Gases are numerous in smoke – mass quantities of Carbon Monoxide lead the list. Concept #2: The Fuels have changed: The contents and structural elements being burned are of LOWER MASS than previous decades. These materials are also more synthetic than ever. Concept #3: The Fuels have triggers There are “Triggers” for Hostile Fire Events. Flash point triggers a smoke explosion. Fire Point triggers rapid fire spread, ignition temperature triggers auto ignition, Backdraft, and Flashover. Hostile fire events (know the warning signs): Flashover: The classic American Version of a Flashover is the simultaneous ignition of fuels within a compartment due to reflective radiant heat – the “box” is heat saturated and can’t absorb any more. The British use the term Flashover to describe any ignition of the smoke cloud within a structure. Signs: Turbulent smoke, rollover, and auto-ignition outside the box. Backdraft: A “true” backdraft occurs when oxygen is introduced into an O2 deficient environment that is charged with gases (pressurized) at or above their ignition temperature. -

Fy 2017 Fy 2018

FY 2017 FY 2018 1 courtesy of Brent Schnupp FROM THE FIRE CHIEF On behalf of the men and women of the Fairfax County Fire and Rescue Department (FCFRD), we are proud to present the Fiscal Year 2017 and 2018 Annual Report. We are committed to providing all hazards emergency response and community risk reduction to over 1.1 million residents and visitors. As you read through the report, we hope you will learn more about how FCFRD can be a resource to help all members of our community. You will note that the volume and complexity of the emergency calls continue to increase. The mental and physical training required to ensure operational readiness in the form of rapid response, compassionate care, and professional service to the community is foremost on the department’s list of priorities. As Fairfax County continues to evolve and transform over time, your Fire and Rescue Department has undergone changes as well. There is an ongoing effort to improve both the effectiveness and ef ciency of our services through innovation and ongoing analysis of both our output and outcomes in all aspects of department operations. Our shared value is that the mission of service to the community always comes rst and our employees are our most important resource. Subsequently, our recruitment and retention programs focus on hiring those candidates who possess the attributes and qualities promulgated in our department’s mission statement and core values and who are the most quali ed candidates who re ect our diverse community. In 2014, the Fire and Rescue Department achieved Insurance Services Of ce (ISO) Class 1 status for re suppression capability. -

Smoke Alarms in US Home Fires Marty Ahrens February 2021

Smoke Alarms in US Home Fires Marty Ahrens February 2021 Copyright © 2021 National Fire Protection Association® (NFPA®) Key Findings Smoke alarms were present in three-quarters (74 percent) of the injuries from fires in homes with smoke alarms occurred in properties reported homei fires in 2014–2018. Almost three out of five home with battery-powered alarms. When present, hardwired smoke alarms fire deathsii were caused by fires in properties with no smoke alarms operated in 94 percent of the fires considered large enough to trigger a (41 percent) or smoke alarms that failed to operate (16 percent). smoke alarm. Battery-powered alarms operated 82 percent of the time. Missing or non-functional power sources, including missing or The death rate per 1,000 home structure fires is 55 percent lower in disconnected batteries, dead batteries, and disconnected hardwired homes with working smoke alarms than in homes with no alarms or alarms or other AC power issues, were the most common factors alarms that fail to operate. when smoke alarms failed to operate. Of the fire fatalities that occurred in homes with working smoke Compared to reported home fires with no smoke alarms or automatic alarms, 22 percent of those killed were alerted by the device but extinguishing systems (AES) present, the death rate per 1,000 reported failed to respond, while 11 percent were not alerted by the operating fires was as follows: alarm. • 35 percent lower when battery-powered smoke alarms were People who were fatally injured in home fires with working smoke present, but AES was not, alarms were more likely to have been in the area of origin and • 51 percent lower when smoke alarms with any power source involved in the ignition, to have a disability, to be at least 65 years were present but AES was not, old, to have acted irrationally, or to have tried to fight the fire themselves. -

List of Fire Departments

Fire Department Name County Address City ZIP Phone Y‐12 Fire Department Anderson P.O. Box 2009 Ms 8124 Oak Ridge 37831‐ (865) 576‐8098 8124 Clinton Fire Department ANDERSON 125 West Broad Street Clinton 37716 865‐457‐2131 City of Rocky Top Fire Department ANDERSON PO Box 66 Rocky Top 37769 865‐426‐8612 Norris Fire Department ANDERSON PO Box 1090 Norris 37828 865‐494‐0880 Marlow Volunteer Fire Department ANDERSON 1019 Oliver Springs Hwy Clinton 37716 865‐435‐1050 Claxton Volunteer Fire Department ANDERSON 2194 Clinton Hwy Powell 37849 865‐945‐1314 Briceville Volunteer Fire Department ANDERSON 1444 Briceville Hwy Briceville 37710‐ 865‐426‐4350 0238 Medford Volunteer Fire Department ANDERSON 3250 Lake City Hwy Rocky Top 37769 865‐426‐2621 City of Oak Ridge Fire Department ANDERSON PO Box 1 Oak Ridge 37831‐ 865‐425‐3520 0001 Andersonville Volunteer Fire Department ANDERSON PO Box 340 Andersonville 37705 865‐494‐0563 Bell Buckle Volunteer Fire Department BEDFORD PO Box 61 Bell Buckle 37020 931‐389‐6940 Wartrace Volunteer Fire Department BEDFORD P.O. Box 158 Wartrace 37183 931‐389‐6144 Shelbyville Fire Department BEDFORD 111 Lane Pkwy Shelbyville 37160 931‐684‐6241 Bedford County Fire Department BEDFORD 104 Prince St Shelbyville 37160 931‐684‐9223 Big Sandy Volunteer Fire Department BENTON P.O. Box 116 Big Sandy 38221 731‐593‐3213 Camden Fire Department BENTON P.O. Box 779 Camden 38320 731‐584‐4656 Holladay‐McIllwain Volunteer Fire Department BENTON PO Box 101 Holladay 38341 731‐584‐8402 Eva Volunteer Fire Department BENTON PO Box 9 Eva 38333 731‐441‐5295 Morris Chapel Volunteer Fire Department BENTON 925 Herrington Rd Camden 38320 731‐441‐8422 Chalk Level Volunteer Fire Department BENTON PO Box 1074 Camden 38320 7312258125 Sandy River Volunteer Fire Department BENTON 8505 Sandy River Rd Camden 38320 731‐249‐4791 South 40 Volunteer Fire Department BENTON 65 Redbud Cove Sugartree 38380 731‐220‐6083 Pikeville Volunteer Fire Department BLEDSOE P.O. -

PRESS RELEASE CITY of BENICIA City Manager’S Office 250 East L Street Benicia, California 94510

PRESS RELEASE CITY OF BENICIA City Manager’s Office 250 East L Street Benicia, California 94510 Contact: Josh Chadwick Acting Deputy Fire Chief (707) 746-4275 [email protected] Welcome Engine 12 in “Wet-Down, Push-In” Ceremony Thursday, August 31st – 9:30 a.m. Fire Station 11 – 150 Military West Benicia, CA (August 23, 2017) — The Benicia Fire Department welcomes Engine 12 to its service fleet in a traditional “wet-down, push-in” ceremony on Thursday, August 31st at 9:30 a.m. The community is invited to join firefighters, other City staff and the City Council in celebrating the arrival of this new piece of safety equipment. The new 2017 Seagrave Pumper fire engine, a state-of-the-art front line pumper, is replacing an existing engine, a 2008 Seagrave, at Fire Station 12. The 2008 engine will become a reserve engine in the department’s fleet. Industry standard for the life of a fire engine is 20 years, with 10 years as “first out” and 10 years in reserve status. “The purchase of this new engine is an investment in the City and its citizens’ safety in regards to fire response,” Acting Deputy Fire Chief Josh Chadwick stated. The 2017 Seagrave custom built pumper features a fully-enclosed stainless steel cab and a stainless-steel body that helps protect firefighters in any rollovers and other crashes. It is also equipped with 360 degree LED lighting “that turns night into day”, which is an important safety feature. It is equipped with a 500-horsepower engine, 1500 gallons per minute pump, a 500-gallon water tank. -

Respirator Usage by Wildland Firefighters

United States Department of Agriculture Fire Forest Service Management National Technology & Development Program March 2007 Tech Tips 5200 0751 1301—SDTDC Respirator Usage by Wildland Firefighters David V. Haston, P.E., Mechanical Engineer Tech Tip Highlights ß Based on a 7-year comprehensive study by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG), a 1997 consensus conference concluded that routine use of air purifying respirators (APRs) should not be required. ß APRs provide protection against some, but not all harmful components of wood smoke, and may expose firefighters to higher levels of unfiltered contaminants, such as carbon monoxide. In addition, APRs do not protect firefighters against superheated gases and do not supply oxygen. ß Firefighters may use APRs on a voluntary basis if certain conditions are met. Introduction All firefighters, fire management officers, and safety personnel should understand the issues related to using air purifying respirators (APRs) in the wildland firefighting environment. This Tech Tip is intended to provide information regarding the regulatory requirements for using APRs, how APRs function, and the benefits and risks associated with their use. Respirator Types and Approvals Respirators are tested and approved by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) in accordance with 42 CFR Part 84 (Approval of Respiratory Protection Devices). Respirators fall into two broad classifications: APRs that filter ambient air, and atmosphere-supplying respirators that supply clean air from another source, such as self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA). APRs include dust masks, mouthpiece respirators (used for escape only), half- and full-facepiece respirators, gas masks, and powered APRs. They use filters or cartridges that remove harmful contaminants when air is passed through the air-purifying element. -

FA-128, a Handbook on Women in Firefighting, January 1993

FA-128/January 1993 A Handbook on Women in Firefighting The Changing Face of the Fire Service Federal Emergency Management Agency United States Fire Administration This document was scanned from hard copy to portable document format (PDF) and edited to 99.5% accuracy. Some formatting errors not detected during the optical character recognition process may appear. The Changing Face of the Fire Service: A Handbook on Women in Firefighting Prepared by: Women in the Fire Service P.O. Box 5446 Madison, WI 53705 608/233-4768 Researchers/Writers: Dee S. Armstrong Brenda Berkman Terese M. Floren Linda F. Willing Disclaimer This publication was prepared for the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s U.S. Fire Administration under contract No. EMW-1-4761. Any points of view or opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the Federal Emergency Management Agency or the U.S. Fire Administration. In August of 1979, the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) convened a “Women in the Fire Service” seminar in College Park, Maryland. This seminar brought together a group of fire service leaders and others to discuss the relatively new phenomenon of women -- perhaps 300 nationwide -- employed as firefighters. Today, women in firefighting positions have increased to approximately 3,000. As a result of the symposium, the USFA in 1980 published a document called The Role of Women in the Fire Service. The publication summarized the issues discussed at the seminar, presented the participants’ recommendations and personal insights into many aspects of women’s work in the fire service, and described existing initiatives and resources in the area. -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

Wildlife Food Plot

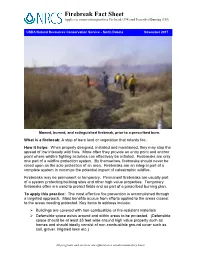

Firebreak Fact Sheet Applies to conservation practices Firebreak (394) and Prescribed Burning (338). USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service - North Dakota November 2017 Mowed, burned, and extinguished firebreak, prior to a prescribed burn. What is a firebreak: A strip of bare land or vegetation that retards fire. How it helps: When properly designed, installed and maintained, they may stop the spread of low intensity wild fires. More often they provide an entry point and anchor point where wildfire fighting activities can effectively be initiated. Firebreaks are only one part of a wildfire protection system. By themselves, firebreaks should never be relied upon as the sole protection of an area. Firebreaks are an integral part of a complete system to minimize the potential impact of catastrophic wildfire. Firebreaks may be permanent or temporary. Permanent firebreaks are usually part of a system protecting building sites and other high value properties. Temporary firebreaks often are used to protect fields and as part of a prescribed burning plan. To apply this practice: The most effective fire prevention is accomplished through a targeted approach. Most benefits accrue from efforts applied to the areas closest to the areas needing protected. Key items to address include: Buildings are covered with non-combustible or fire-resistant materials. Defensible space exists around and within areas to be protected. (Defensible space should be at least 35 feet wide around high value property such as homes and should ideally consist of non-combustible ground cover such as soil, gravel, irrigated lawn etc.) All programs and services are offered on a nondiscriminatory basis. -

Advisory U.S.Deportment of Transportution Fedeml Aviation Circular

Pc/ Advisory U.S.Deportment of Transportution Fedeml Aviation Circular Subject: POWERPLANT INSTALLATION AND Date: 2/6/W ACNo: 20- 135 PROPULSION SYSTEM COMPONENT FIRE Initiated by: ANM- 110 Change: PROTECTION TEST METHODS, STANDARDS, AND CRITERIA. 1 PURPOSE. This advisory circular (AC) provides guidance for use in demonstrating compliance with the powerplant fire protection requirements of the Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR). Included in this document are methods for fire testing of materials and components used in the propulsion engines and APU installations, and in areas adjacent to designated fire zones, as well as the rationale for these methods. Since the method of compliance presented in this AC is not mandatory, the terms "shall" and "must," as used in this AC, apply only to an applicant who chooses to follow this particular method without deviation. 2 RELATED FAR SECTIONS. The applicable FAR sections are listed in appendix 1 of this AC. 3 BACKGROUND. Although 5 1.1 of the FAR provides general definitions for the terms "fireproof" and "fire resistant," these definitions do not specify heat intensity, temperature levels, duration (exposure time), or an appropriate wall thickness or other dimensional characteristics for the purpose intended. With the advent of surface coatings (i.e., ablative/ intumescent), composites, and metal honeycomb for acoustically treated ducting, cowling, and other components which may form a part of the nacelle firewall, applicant confusion sometimes exists as to how compliance can be shown, particularly with respect to the definition of "fireproof" and "fire resistant" as defined in 5 1.1. 4 DEFINITIONS. For the purposes of this AC, the following definitions . -

Federal Funding for Wildfire Control and Management

Federal Funding for Wildfire Control and Management Ross W. Gorte Specialist in Natural Resources Policy July 5, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33990 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Federal Funding for Wildfire Control and Management Summary The Forest Service (FS) and the Department of the Interior (DOI) are responsible for protecting most federal lands from wildfires. Wildfire appropriations nearly doubled in FY2001, following a severe fire season in the summer of 2000, and have remained at relatively high levels. The acres burned annually have also increased over the past 50 years, with the six highest annual totals occurring since 2000. Many in Congress are concerned that wildfire costs are spiraling upward without a reduction in damages. With emergency supplemental funding, FY2008 wildfire funding was $4.46 billion, more than in any previous year. The vast majority (about 95%) of federal wildfire funds are spent to protect federal lands—for fire preparedness (equipment, baseline personnel, and training); fire suppression operations (including emergency funding); post-fire rehabilitation (to help sites recover after the wildfire); and fuel reduction (to reduce wildfire damages by reducing fuel levels). Since FY2001, FS fire appropriations have included funds for state fire assistance, volunteer fire assistance, and forest health management (to supplement other funds for these three programs), economic action and community assistance, fire research, and fire facilities. Four issues have dominated wildfire funding debates. One is the high cost of fire management and its effects on other agency programs. Several studies have recommended actions to try to control wildfire costs, and the agencies have taken various steps, but it is unclear whether these actions will be sufficient.