CARMACK-THESIS.Pdf (1.039Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2002 (PDF)

CIVILRIGHTS WINTER 2002 JOURNAL ALSO INSIDE: EQUATIONS: AN INTERVIEW WITH BOB MOSES FLYING HISTORY AS SENTIMENTAL EDUCATION WHILE WHERE ARE YOU REALLY FROM? ASIAN AMERICANS AND THE PERPETUAL FOREIGNER SYNDROME ARAB MANAGING THE DIVERSITY Lessons from the Racial REVOLUTION: BEST PRACTICES FOR 21ST CENTURY BUSINESS Profiling Controversy U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS CIVILRIGHTS WINTER 2002 JOURNAL The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, bipartisan agency first established by Congress in 1957. It is directed to: • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are being deprived of their right to Acting Chief vote by reason of their race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, Terri A. Dickerson or by reason of fraudulent practices; • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal Managing Editor protection of the laws under the Constitution because of race, color, religion, sex, David Aronson age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice; Copy Editor • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to discrimination or denial of equal Dawn Sweet protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice; Editorial Staff • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information in respect to discrimination or Monique Dennis-Elmore denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, Latrice Foshee disability, or national origin; Mireille Zieseniss • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress; • Issue public service announcements to discourage discrimination or denial of equal Interns protection of the laws. Megan Gustafson Anastasia Ludden In furtherance of its fact-finding duties, the Commission may hold hearings and issue Travis McClain subpoenas for the production of documents and the attendance of witnesses. -

Title of Book/Magazine/Newspaper Author/Issue Datepublisher Information Her Info

TiTle of Book/Magazine/newspaper auThor/issue DaTepuBlisher inforMaTion her info. faciliT Decision DaTe censoreD appealeD uphelD/DenieD appeal DaTe fY # American Curves Winter 2012 magazine LCF censored September 27, 2012 Rifts Game Master Guide Kevin Siembieda book LCF censored June 16, 2014 …and the Truth Shall Set You Free David Icke David Icke book LCF censored October 5, 2018 10 magazine angel's pleasure fluid issue magazine TCF censored May 15, 2017 100 No-Equipment Workout Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 of the Most Beautiful Women in Painting Ed Rebo book HCF censored February 18, 2011 100 Things You Will Never Find Daniel Smith Quercus book LCF censored October 19, 2018 100 Things You're Not Supposed To Know Russ Kick Hampton Roads book HCF censored June 15, 2018 100 Ways to Win a Ten-Spot Comics Buyers Guide book HCF censored May 30, 2014 1000 Tattoos Carlton Book book EDCF censored March 18, 2015 yes yes 4/7/2015 FY 15-106 1000 Tattoos Ed Henk Schiffmacher book LCF censored December 3, 2007 101 Contradictions in the Bible book HCF censored October 9, 2017 101 Cult Movies Steven Jay Schneider book EDCF censored September 17, 2014 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius Brad Graham & Kathy McGowan book HCF censored August 31, 2011 yes yes 9/27/2011 FY 12-009 110 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories & Stars: At this Theater Viagas & Botto Applause Theater & Cinema Books book LCF censored November 30, 2018 113 Minutes James Patterson Hachette books book -

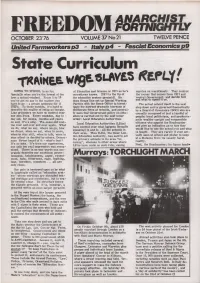

Scanned Image

R HI T OCTOBER 2376 VOLUME 37 No 21 TWELVE PENCE UnitedFarmworkersn3 ~ Italyn4 - FascistEconomics£9 Aiuse LN/£5 e. 1.! GOING TO SCHOOL is no fun. of Education and Science or DES as he's carries on mercilessly. They control Specially when you're the lowest of the sometimes known. (DES is the tip of the money that comes from DES and low: a school-student. From 5 to 16 the education system pyramid). He central Government. and decide how you've got no say in the matter: you does things like set up Special Working and what to spend it on. have to go - a prison sentence for ll Parties with the Home Office to invest- The actual school itself is the next years. To those outside, it's hard to igate the current dramatic increase of step down and is governed theoretically describe the reality of being an inmate. deliberate fires at schools, and general- by a Board of Governors (BOG) who are Like prisoners we have no control over ly sees that Government policy on educ- ususally composed of just a handful of our own lives. Every weekday, day in - ation is carried out by the next lower people; local politicians, and predomin- day out, for weeks, months and years order: Local Education Authorities. antly wealthy upright and responsible on end, it's a slog. The same old rout- Local Education Authorities (LEAs) citizens who appoint the Headmaster ine over and over and over again. What and give an indication as to how they we do, what we say, where we go, how " have control over what happens (broadly speaking) in and to - all the schools in would like to see the school run and what we dress, when we eat. -

Local Dimensions of the Colombian Conflict: Order and Security in Drug Trafficking

Working Paper Series Working Paper 15 Local Dimensions of the Colombian Conflict: Order and Security in Drug Trafficking Ingrid J. Bolívar Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Conflict Research Unit July 2003 Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague Phone number: # 31-70-3141950 Telefax: # 31-70-3141960 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/cru © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. © Clingendael Institute 3 Table of Contents Foreword 5 List of Abbreviations 7 Executive Summary 9 I. Introduction 11 II. The Local Dimension of the Political Economy of the Colombian Conflict 15 2.1. Territorial Rationalities of the Conflict’s Protagonists 15 2.2. Guerrilla Finance 16 2.3. Paramilitary Finance 19 2.4. The Nexus of Economy, Region and Politics 20 2.5. The Colombian Economy and the Emergence of the Guerrillas 20 2.5.1. Guerrillas and Coca 22 2.5.2. Guerrillas and Legitimacy 25 2.6. ‘Plan Colombia’ 27 2.7. Developments in Urabá 28 2.8. The ELN and Oil 29 2.9. The United States and Oil 30 2.10. Control over Local Governments and Taxes 31 Bibliography 36 © Clingendael Institute 5 Foreword This paper is part of a larger research project, 'Coping with Internal Conflict' (CICP), which was executed by the Conflict Research Unit of the Netherlands Institute of International Relations 'Clingendael' for the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

Cia-Rdp90-00845R000100150006-5

Approved For Release 2010/06/03 : CIA-RDP90-00845R000100150006-5 :}i .. ,.,. 1,.,: .. ; . "' ' The Magazine For People Who Need To Know ( Volume 4, Number 1 $2 NOTES ON: PRINCETON-CIA➔ MIDDLE EAST .. p. 3 JOAN BAEZ-TOM DOOLEY OF THE '80's .......... p. 4 TRANSAFRICA??? p.5 US INTERVF"NTION IN AFGHANISTAN ................................. p. 8 CIA: PLO'lVSHARES INTO SWORDS? .................................. p. 19 · CIA IN INDONESIA: 1965 .................................................... p. 23 US INTELLIGENCE IN NORWAY ......................................... p. 33 US INTELLIGENCE: GUATEMALA .................................................................... p. 42 HAITI ...................................................... · _ ......................... p. 43 FRANCE ..................................................................... ...· · .. p. 43 JAPAN : ..... •···········:······: ............... ;·•·······--····:··················.··· p. 44 ENGLAND ............ : .._ .............................................· ........... p. 45 Approved For Release 2010/06/03 : CIA-RDP90-00845R000100150006-5 For Release 2010/06/03 : CIA-RDP90-00845R000100150006-5 Approved •,It . ,,. Unique, indeed. Obviously, this depot could serve as a secret staging EDITORIAL area for the Bhah. loyalists led by the Shah's son who trained with these same The response to our "alert and plea" officers in Texas and who i�- also in the for public suppo_rt has given us the US. The American and Iranian peoples courage and strength to continue and have a right -

Toward a Libertarian Society 2014.Indb

TÊóÙ L®ÙãÙ®Ä SÊ®ãù Th e Mises Institute dedicates this volume to all of its generous donors and wishes to thank these Patrons, in particular: top dogTM ~ Anonymous, Michael G. Keller, DO ~ Anonymous (3), Wesley and Terri Alexander, Harvey Allison, Th omas Balmer, Steven R. Berger, Bob and Rita Bost, Mary E. Braum, Wayne Chapeskie, Andrew S. Cofrin, Mike Fox, Kevin R. Griffi n, Jeff rey Harding, Dr. Ronald J. Legere II, Robert A. Moore, Gregory and Joy Morin, Nelson and Mary Nash, Mr. and Mrs. William C. Newton, Paul F. Peppard, Rafael A. Perez-Mera, MD, Daniel J. Rozeboom, Chris Rufer, William P. Sarubbi, Donald E. Siemers, Henri Etel Skinner, Hubert John Strecker, John Tubridy, Joseph Vierra, Dr. Th omas L. Wenck, Brian Wilton, Tom Winn, Mr. and Mrs. Walter Woodul III, Guillermo M. Yeatts TÊóÙ L®ÙãÙ®Ä SÊ®ãù W½ãÙ B½Ê» M ISESI NSTITUTE Published 2014 by the Mises Institute. Th is work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Mises Institute 518 West Magnolia Avenue Auburn, Alabama 36832 mises.org ISBN: 978-1-61016-595-2 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-61016-631-7 (large print edition) eISBN: 978-1-61016-629-4 (digital) To the Memory of a Great Man, Murray N. Rothbard CÊÄãÄãÝ Preface . 11 Introduction . 15 I. Foreign Policy . 19 1. Libertarian Warmongers: A Contradiction in Terms . .21 2. Bloodthirsty “Libertarians”: Why Warmongers Can’t Be Pro-Liberty . .24 3. Th irteenth Floors . .27 4. -

Egalitarianism As a Revolt Against Nature and Other Essays

EGALITARIANISM AS A REVOLT AGAINST NATURE AND OTHER ESSAYS SECOND EDITION MURRAY N. ROTHBARD EGALITARIANISM AS A REVOLT AGAINST NATURE AND OTHER ESSAYS SECOND EDITION MURRAY N. ROTHBARD LUDWIG VON MISES INSTITUTE AUBURN, ALABAMA Second Edition Copyright © 2000 by The Ludwig von Mises Institute. Index prepared by Richard Perry. First Edition Copyright © 1974 (Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature, R.A. Childs, Jr., ed., Washington: Libertarian Review Press). Cover illustration by Deanne Hollinger. Copyright © Same Day Poster Service. All rights reserved. Written permission must be secured from the pub- lisher to use or reproduce any part of this book, except for brief quota- tions in critical reviews or articles. Published by The Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832-4528, www.mises.org. ISBN: 0-945466-23-4 CONTENTS Introduction to the Second Edition......................................................v Introduction to the First Edition........................................................xv Foreword to the 1974 Edition (R.A. Childs, Jr.)................................xxi Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature...........................................1 Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty.........................................21 The Anatomy of the State...................................................................55 Justice and Property Rights................................................................89 War, Peace, and the State..................................................................115 -

The Ku Klux Klan and Freemasonry in 1920S America

FIGHTING FRATERNITIES: THE KU KLUX KLAN AND FREEMASONRY IN 1920S AMERICA Submitted by Miguel Hernandez, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, September 2014. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signed …………………………………………………………………………. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout this project, I have been supported and assisted by a number of people and institutions without whom this thesis could not have been completed. I would struggle to mention all the people who have helped me over the years, but I would like to thank a few key individuals and institutions. First, I would like to express my gratitude to the Arts and Humanities Research Council of the UK for financing my studies over the past three years. I hope that they consider my work a worthwhile investment. I would also like to thank the AHRC for funding my placement at the Library of Congress, it proved to be an invaluable experience. Several historians have also offered me valuable advice throughout my studies. I am indebted to Jeffrey Tyssens, Bob James, Cecile Revauger, Andrew Pink, and Mark N. Morris for all their help. Librarians and archivists are truly some of the most overlooked members of the historical community, but their work proved vital for the completion of this thesis. -

Covery and Stillness, of Tremors Appropriate Agencies

CivilizationCivilization isis thethe amputationamputation ofof everythingeverything thatthat everever happenedhappened toto us.us. AnAn experimentexperiment createdcreated byby aliensaliens unableunable toto havehave sex.sex. CivilizationCivilization isis thethe molestationmolestation GREENGREEN ANARCHYANARCHY anan anti-civilizationanti-civilization journaljournal ofof theorytheory andand actionaction ofof everythingeverything wewe couldcould be.be. AA giantgiant repressionrepression meltingmelting intointo suppressionsuppression ISSUE #13 So that YOU never say what YOU mean. So that YOU never say what YOU mean. SUMMER 2003 Civilization is breathing down our necks Civilization is breathing down our necks $3 USA $4 CAN $5 WORLD SplittingSplitting usus apart.apart. FREE TO PRISONERS WeWe areare wreckagewreckage withwith beatingbeating hearts.hearts. CivilizationCivilization isis aa cancan ofof hairsprayhairspray SprayingSpraying forfor thethe senselesssenseless vainvain IntoInto aa hairnethairnet ...... OnlyOnly everever meantmeant toto bebe waves.waves. Civilization,Civilization, genocidegenocide beliefs,beliefs, MoralisticMoralistic See-throughSee-through lacelace blousesblouses Missiles,Missiles, ballisticballistic LackadaisicalLackadaisical MelancholyMelancholy redred lipsticklipstick WhenWhen oneone feelsfeels nauseous,nauseous, ButBut doesndoesn’’tt feelfeel sick.sick. CivilizationCivilization knewknew whowho youyou werewere beforebefore youyou werewere eveneven bornborn ForgaveForgave YouYou whenwhen youyou thoughtthought YouYou neededneeded -

Acker Chapbook 2016.Indd

ACKER RECIPIENTS 2016 Arturo Vega............................................05 Kate Simon.............................................22 Anthony Haden-Guest.............................06 Robert Butcher.......................................23 John Holmstrom.....................................07 Penny Arcade..........................................24 Carolyn Ratcliffe.....................................08 Eliot Katz...............................................25 Dr. David Ores, M.D. ..............................09 Michael McCabe.....................................26 Alice Torbush..........................................10 Nick Bubash...........................................27 Chris Flash.............................................11 Puma Perl..............................................28 Leonard Abrams......................................12 Dick Zigun..............................................29 Brian “Hattie” Butterick...........................13 Rev. Richard Ryler..................................30 Sara Driver.............................................14 Shiv Mirabito..........................................31 Steve Zeitlin............................................15 Zia Ziprin................................................32 Chris Rael..............................................16 Pat Ivers & Emily Armstrong....................33 Samoa Moriki.........................................17 Antony Zito.............................................34 David Godlis...........................................18 Curt -

Museum of the Moving Image Presents a Panorama of Public Access Television in New York City

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE PRESENTS A PANORAMA OF PUBLIC ACCESS TELEVISION IN NEW YORK CITY Series, running February 11 through 20, opens with a reunion of 20 pioneers and producers including George Stoney, Anton Perich, Paul Tschinkel, Jaime Davidovich, Lisa Yapp, Scott Lewis, Gary Winter and “Rapid T. Rabbit” Long before YouTube, public access cable television was an electronic hotline between amateur creators and the masses. From February 11 through 20, 2011, Museum of the Moving Image presents the first museum retrospective devoted to public access cable. The series, “ TV Party: A Panorama of Public Access Television in New York City ” will commemorate the 40th anniversary of cable access in this city, featuring dispatches from the fringe spanning four decades of “user generated,” do-it-yourself television. Guest-curated by Leah Churner and Nicolas Rapold, the series begins on Friday, February 11, with a live event featuring luminaries of the medium, including veteran filmmaker and “godfather of public access” George Stoney along with the producers of “ Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party ,” “ Anton Perich Presents ,” “ Paul Tschinkel’s Inner- Tube ,” “ The Live! Show ,” “ The Rapid T. Rabbit Show ,” “ Tomorrow’s Television Tonight ,” “ The Scott & Gary Show ” and “ Wild Record Collection ” and more. TV Party continues on February 12, 13, 19 and 20 with screening programs devoted to the “genres” of public access: “interactive” call-in talk shows, rock ‘n’ roll showcases, avant-garde variety programs, plain old teenage anarchy, and late-night “blue” fare that skirted FCC decency regulations. “New York’s public access channels harnessed mysteries of human nature never before seen on television,” said Ms. -

Mycelium Is the Message: Open Science, Ecological Values, and Alternative Futures with Do-It-Yourself Mycologists

University of California Santa Barbara Mycelium is the Message: open science, ecological values, and alternative futures with do-it-yourself mycologists A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Joanna Beth Steinhardt Committee in charge: Professor Mary Hancock, Chair Professor Casey Walsh Professor Ann Taves September 2018 The Dissertation of Joanna Steinhardt is approved. ______________________________________ Professor Casey Walsh ______________________________________ Professor Ann Taves ______________________________________ Professor Mary Hancock, Committee Chair September 2018 Mycelium is the Message: open science, ecological values, and alternative futures with do-it-yourself mycologists Copyright © 2018 by Joanna Beth Steinhardt !iii To my parents !iv Acknowledgements Thank you to everyone who made this undertaking possible: first and foremost, my advisor Mary Hancock, for supporting me even as my project wandered into unplanned territory; my committee members, Casey Walsh and Ann Taves for helpful advice and feedback along the way; to my mother, who jumped wholeheartedly onto the mushroom train and even promised to read my dissertation; my sister, who gave me a place to crash in Portland and shared her Cascadian local knowledge with me; Larry and Louise, who hosted us in Eugene and shared their love of mushrooms and medicinal herbs; and all of my friends in Santa Barbara and the Bay Area that made the life of a toiling graduate student a little more tolerable, especially Miriam and Tak (who have fed me more times than I can count), the Blanket Fort buddies (whose love of shrombies kept me inspired), Mark Deutsch, Mia Bruch, Leslie Outhier, Francis Melange, Shayla Monroe, Patricia Kubala, Phil Ross, as well as many others whom I met in the last few years through the shared acquaintance of Kingdom Fungi and fascination with interspecies relationships.