Local Dimensions of the Colombian Conflict: Order and Security in Drug Trafficking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Economic and Political Implications

Order Code RL34470 The U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Economic and Political Implications May 1, 2008 M. Angeles Villarreal Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division The U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement: Economic and Political Implications Summary Implementing legislation for a U.S.-Colombia Free Trade Agreement (CFTA) (H.R. 5724/S. 2830) was introduced in the 110th Congress on April 8, 2008 under Title XXI (Bipartisan Trade Promotion Authority Act of 2002) of the Trade Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-210). The House leadership considered that the President had submitted the implementing legislation without sufficient coordination with the Congress, and on April 10 the House voted 224-195 to make certain provisions in § 151 of the Trade Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-618), the provisions establishing expedited procedures, inapplicable to the CFTA implementing legislation (H.Res 1092). The CFTA is highly controversial and it is currently unclear whether or how Congress will consider implementing legislation in the future. The agreement would immediately eliminate duties on 80% of U.S. exports of consumer and industrial products to Colombia. An additional 7% of U.S. exports would receive duty-free treatment within five years of implementation and all remaining tariffs would be eliminated within ten years after implementation. The agreement also contains provisions for market access to U.S. firms in most services sectors; protection of U.S. foreign direct investment in Colombia; intellectual property rights protections for U.S. companies; and enforceable labor and environmental provisions. The United States is Colombia’s leading trade partner. -

World Bank Document

APPENDIX III No. E llla RESTRICTED Public Disclosure Authorized This report is restricted to use within the Bank. INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT •Public Disclosure Authorized RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE ECONOMY OF COLOMBIA October 19, 1950 •Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Economic Department Prepared by: Jacques Torfs COLOMBIA ESSEa~IAL STATISTICS Area: 450. 000 square mile s. Populat_ion (1949): 10.5 million. Rate of increase: 2.1% per annum. Currency: Unit: Peso. furfty: 1 .. 95 pesos equals US$. (51.3 cents equals peso). Trade: I Impo rt s 1948: ( c • i . f • ) US$ 346.0 million. Imports 1949: (c.i.f.) uS$ 252.0 million. E&Ports 1948: (f.o.b.) uS$ 286.0 million. Exports 1949: (f.o.b.) US$ 303.0 million • Budget: • --TOtal expendi tures 1948: Ps.$ 427 million. Total expenditures 1949: Ps.$ 449 million Total revenues 1948: Ps.$ 339 million~ Total reV'enues f949": PS.$ 403 million. External Debt: (IJec. 31, 1949) (including undi sbursed commitment) Principal, National Bonded Debt: .. : - US$ 47.9 million. (of '~hich Sterling bonds US$ 6.2 million) Prlncipal, otnel' National: US$ 56.1 million. (including Exim-IBRD) llipartmental and 1:".nicipal, ~ong-term debt: US$ 42.2 million. E.xport-Impo;·~ Bank Debt: (Sept. 30, 1950) Authorized (not including past operat ions) : uS$ 54.1 million. • Disbursed: US$ 36.9 million. "OUtstanding: US$ 2203 million. Balance not yet di sbursed: US$ 17.2 million, Co st-of-L1 vinE; I ndex: (Raga ta) (FeD. 1937 equals 100) December, 1948~ 285 Y December, 191.~9: 304 July, 1950: 386 Tot a1 Gol d and Exchange Be serve s: December, 1948: US$ 88 million. -

Winter 2002 (PDF)

CIVILRIGHTS WINTER 2002 JOURNAL ALSO INSIDE: EQUATIONS: AN INTERVIEW WITH BOB MOSES FLYING HISTORY AS SENTIMENTAL EDUCATION WHILE WHERE ARE YOU REALLY FROM? ASIAN AMERICANS AND THE PERPETUAL FOREIGNER SYNDROME ARAB MANAGING THE DIVERSITY Lessons from the Racial REVOLUTION: BEST PRACTICES FOR 21ST CENTURY BUSINESS Profiling Controversy U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS CIVILRIGHTS WINTER 2002 JOURNAL The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, bipartisan agency first established by Congress in 1957. It is directed to: • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are being deprived of their right to Acting Chief vote by reason of their race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, Terri A. Dickerson or by reason of fraudulent practices; • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal Managing Editor protection of the laws under the Constitution because of race, color, religion, sex, David Aronson age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice; Copy Editor • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to discrimination or denial of equal Dawn Sweet protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice; Editorial Staff • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information in respect to discrimination or Monique Dennis-Elmore denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, Latrice Foshee disability, or national origin; Mireille Zieseniss • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress; • Issue public service announcements to discourage discrimination or denial of equal Interns protection of the laws. Megan Gustafson Anastasia Ludden In furtherance of its fact-finding duties, the Commission may hold hearings and issue Travis McClain subpoenas for the production of documents and the attendance of witnesses. -

2003-08 the Interface Between Domestic and International Factors in Colombia's War System.Pdf

Working Paper Series Working Paper 22 The Interface Between Domestic and International Factors in Colombia’s War System Nazih Richani Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Conflict Research Unit August 2003 Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ Clingendael 7 2597 VH The Hague P.O. Box 93080 2509 AB The Hague Phone number: # 31-70-3141950 Telefax: # 31-70-3141960 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.clingendael.nl/cru © Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingendael. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holders. Clingendael Institute, P.O. Box 93080, 2509 AB The Hague, The Netherlands. ã Clingendael Institute 3 Table of Contents Foreword 5 Abbreviations 7 I. Introduction 9 II. Multinational Corporations and the War System’s Economy 11 2.1. Multinationals and the Guerrillas 13 2.2. Multinational Corporations and the State 14 2.3. Multinationals and the Paramilitaries: Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC, the United Self-Defences of Colombia) 14 III. International-Regional Networks and Commodities Fuelling the Internal Conflict 17 3.1. Narcotrafficking 17 3.2. The State Hegemonic Crisis and Narcotrafficking 20 3.3. Ransom/Kidnapping, Gold, Emeralds and the Arms’ Trade 22 3.4. Colombia’s Conflict and the Regional Nexus 25 3.5. The United States’ Policy: ‘Plan Colombia’ and the ‘War on Terrorism’ 27 IV. International Trade Regimes and Colombia’s War System 29 4.1. The Drug Prohibition Regime and Money Laundering 29 4.2. -

Essays on the Political Economy of Development

The London School of Economics and Political Science Essays on the Political Economy of Development Luis Roberto Mart´ınezArmas A thesis submitted to the Department of Economics of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2016. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of approximately 47,301 words. Statement of Conjoint Work I confirm that Chapter 2 was jointly co-authored with Juan Camilo C´ardenas, Nicol´asDe Roux and Christian Jaramillo. I contributed 25 % of this work. 2 Abstract The present collection of essays studies some of the ways in which the interaction of economic and political forces affects a country's development path. The focus of the thesis is on Colombia, which is a fertile setting for the study of the political economy of development given its long-lasting internal conflict, the multiple reforms to the functioning of the state that have taken place in the last decades and the availability of high quality sub-national data. -

Plan Colombia: Illegal Drugs, Economic Development, and Counterinsurgency – an Econometric Analysis of Colombia’S Failed War

This is the accepted manuscript of an article published by Wiley in Development Policy Review available online: https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12161 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/31771/ Plan Colombia: Illegal Drugs, Economic Development, and Counterinsurgency – An Econometric Analysis of Colombia’s Failed War Abstract: This article examines the socioeconomic effects of the illegal drug industry on economic and social development in Colombia. It shows that illegal drugs have fostered violence and have had a negative effect on economic development. This article also shows that the anti-drug policy Plan Colombia has been a rather ineffective strategy to decrease drug production, generate economic development, and reduce violence. Since this study includes both, a statistical analysis of the effects violence and illegal drugs have on the economic growth of Colombia, as well as an enhanced evaluation of the policy programme Plan Colombia, it fills the gap between existing empirical studies about the Colombian illegal drug industry and analyses of Plan Colombia. 1. Introduction In many Latin American countries there is an on-going discussion on how to tackle the economic, social and political problems that are caused not only by the illegal drug industry itself but much more by the policies that focus on repressing production and trafficking of illegal drugs. The need to reform international drug policy and change the strategy in the war on drugs was publicly emphasised by a report of the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy (2009). Led by three former Latin American presidents and the Global Commission on Drugs and Democracy, the report recognised that the war on drugs in many Latin American countries has failed (Campero et al., 2013). -

THE IMPACT of COFFEE PRODUCTION on the ECONOMY of COLOMBIA By

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College 5-5-2017 The mpI act of Coffee rP oduction on the Economy of Colombia Luke Alexander Ferguson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the International Business Commons Recommended Citation Ferguson, Luke Alexander, "The mpI act of Coffee Production on the Economy of Colombia" (2017). Senior Theses. 153. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/153 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF COFFEE PRODUCTION ON THE ECONOMY OF COLOMBIA By Luke Alexander Ferguson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors from the South Carolina Honors College May 2017 Approved: Dr. Robert Gozalez Director of Thesis Dr. Hildy Teegen Second Reader Steve Lynn, Dean For South Carolina Honors College FERGUSON: THE IMPACT OF COFFEE IN COLOMBIA 2 I. ABSTRACT This senior thesis seeks to determine the impact that the level of coffee production in Colombia has on economic wellbeing in the country. As a proxy for economic wellbeing in different arenas, I look at the income, health, and education variables of GDP, infant mortality rate, and secondary education enrollment. I use a Two-Stage Least Squares regression model to estimate this impact, with lagged international coffee prices and the occurrence of the fungal plant disease coffee leaf rust as instruments to account for endogeneity. The data which I use in this project include country-level indicators from the World Bank and monthly coffee production quantities from Colombia’s National Federation of Coffee Growers. -

Redalyc.Emerging Markets Integration in Latin America (MILA)

Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science ISSN: 2077-1886 [email protected] Universidad ESAN Perú Lizarzaburu Bolaños, Edmundo R.; Burneo, Kurt; Galindo, Hamilton; Berggrun, Luis Emerging Markets Integration in Latin America (MILA) Stock market indicators: Chile, Colombia, and Peru Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science, vol. 20, núm. 39, diciembre, 2015, pp. 74-83 Universidad ESAN Surco, Perú Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=360743432002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science 20 (2015) 74–83 Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Science www.elsevier.es/jefas Article Emerging Markets Integration in Latin America (MILA) Stock market indicators: Chile, Colombia, and Peru a,∗ b c d Edmundo R. Lizarzaburu Bolanos˜ , Kurt Burneo , Hamilton Galindo , Luis Berggrun a Universidad ESAN, Lima, Peru b Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Lima, Peru c Universidad del Pacífico, Lima, Peru d Universidad Icesi, Cali, Colombia a b s t r a c t a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: This study aims to determine the impact of the Latin American Integrated Market (MILA) start-up in Received 7 May 2015 the main indicators of the stock markets of the countries that conform it (Chile, Colombia, and Peru). Accepted 18 August 2015 At the end, several indicators were reviewed to measure the impact on profitability, risk, correlation, and trading volume between markets, using indicators such as: annual profitability, standard deviation, JEL classification: correlation coefficient, and trading volume. -

The Political Economy of Resource Conflicts and Forced Migration

Societies Without Borders Volume 12 Article 16 Issue 1 Human Rights Attitudes 2017 The olitP ical Economy of Resource Conflicts and Forced Migration: Why Afghanistan, Colombia and Sudan Are the World's Longest Forced Migration Tarique Niazi PhD University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, [email protected] Jeremy Hein PhD University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Niazi, Tarique & Jeremy Hein. 2017. "The oP litical Economy of Resource Conflicts and Forced Migration: Why Afghanistan, Colombia and Sudan Are the World's Longest Forced Migration." Societies Without Borders 12 (1). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb/vol12/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cross Disciplinary Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Societies Without Borders by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Niazi and Hein: The Political Economy of Resource Conflicts and Forced Migration: The Political Economy of Resource Conflicts and Forced Migration: Why Afghanistan, Colombia and Sudan Are the World’s Longest Forced Migration Crises Tarique Niazi, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Jeremy Hein, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire ABSTRACT Afghanistan, Colombia, and Sudan are the world’s three longest producers of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs). Why? To answer this question, we evaluate the conventional and dominant geopolitical model of forced migration, as well as alternative models that focus on resource-based conflicts and political economy. -

Title of Book/Magazine/Newspaper Author/Issue Datepublisher Information Her Info

TiTle of Book/Magazine/newspaper auThor/issue DaTepuBlisher inforMaTion her info. faciliT Decision DaTe censoreD appealeD uphelD/DenieD appeal DaTe fY # American Curves Winter 2012 magazine LCF censored September 27, 2012 Rifts Game Master Guide Kevin Siembieda book LCF censored June 16, 2014 …and the Truth Shall Set You Free David Icke David Icke book LCF censored October 5, 2018 10 magazine angel's pleasure fluid issue magazine TCF censored May 15, 2017 100 No-Equipment Workout Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 No-Equipment Workouts Neila Rey book LCF censored February 19,2016 100 of the Most Beautiful Women in Painting Ed Rebo book HCF censored February 18, 2011 100 Things You Will Never Find Daniel Smith Quercus book LCF censored October 19, 2018 100 Things You're Not Supposed To Know Russ Kick Hampton Roads book HCF censored June 15, 2018 100 Ways to Win a Ten-Spot Comics Buyers Guide book HCF censored May 30, 2014 1000 Tattoos Carlton Book book EDCF censored March 18, 2015 yes yes 4/7/2015 FY 15-106 1000 Tattoos Ed Henk Schiffmacher book LCF censored December 3, 2007 101 Contradictions in the Bible book HCF censored October 9, 2017 101 Cult Movies Steven Jay Schneider book EDCF censored September 17, 2014 101 Spy Gadgets for the Evil Genius Brad Graham & Kathy McGowan book HCF censored August 31, 2011 yes yes 9/27/2011 FY 12-009 110 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories & Stars: At this Theater Viagas & Botto Applause Theater & Cinema Books book LCF censored November 30, 2018 113 Minutes James Patterson Hachette books book -

Scanned Image

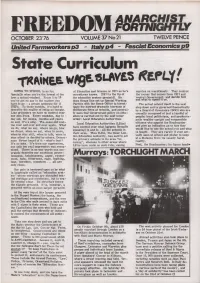

R HI T OCTOBER 2376 VOLUME 37 No 21 TWELVE PENCE UnitedFarmworkersn3 ~ Italyn4 - FascistEconomics£9 Aiuse LN/£5 e. 1.! GOING TO SCHOOL is no fun. of Education and Science or DES as he's carries on mercilessly. They control Specially when you're the lowest of the sometimes known. (DES is the tip of the money that comes from DES and low: a school-student. From 5 to 16 the education system pyramid). He central Government. and decide how you've got no say in the matter: you does things like set up Special Working and what to spend it on. have to go - a prison sentence for ll Parties with the Home Office to invest- The actual school itself is the next years. To those outside, it's hard to igate the current dramatic increase of step down and is governed theoretically describe the reality of being an inmate. deliberate fires at schools, and general- by a Board of Governors (BOG) who are Like prisoners we have no control over ly sees that Government policy on educ- ususally composed of just a handful of our own lives. Every weekday, day in - ation is carried out by the next lower people; local politicians, and predomin- day out, for weeks, months and years order: Local Education Authorities. antly wealthy upright and responsible on end, it's a slog. The same old rout- Local Education Authorities (LEAs) citizens who appoint the Headmaster ine over and over and over again. What and give an indication as to how they we do, what we say, where we go, how " have control over what happens (broadly speaking) in and to - all the schools in would like to see the school run and what we dress, when we eat. -

CARMACK-THESIS.Pdf (1.039Mb)

Copyright by Kara Elizabeth Carmack 2010 The Thesis Committee for Kara Elizabeth Carmack Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Anton Perich Presents and TV Party: Queering Television on Manhattan Public Access Channels, 1973-1982 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Ann Reynolds Roberto Tejada Anton Perich Presents and TV Party: Queering Television via Manhattan Public Access Channels, 1973-1982 by Kara Elizabeth Carmack, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2010 Acknowledgements I first want to extend my gratitude to my advisor, Ann Reynolds, for supporting and encouraging my pursuit of this rather obscure topic, and to Roberto Tejada for his invaluable comments and suggestions. I also want to thank Ann Cvetkovich for her influential seminar, which greatly informed this thesis. I would also like to thank my fellow classmates, Emily Bierman and Alexia Rostow, for their words of encouragement and for keeping me company during the many long evenings in Austin‟s coffee shops. Finally, I am especially grateful for a family willing to answer my phone calls at all hours of the day and for always urging me forward. I owe most of this thesis to my mom for her unflagging support over the past two years. 27 July 2010 iv Abstract Anton Perich Presents and TV Party: Queering Television via Manhattan Public Access Channels, 1973-1982 Kara Elizabeth Carmack, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2010 Supervisor: Ann Reynolds Though largely overlooked in academia, Manhattan public access television became a forum that allowed a variety of behaviors, sexualities, and genders to invade a highly controlled hegemonic apparatus in the 1970s and early 1980s.