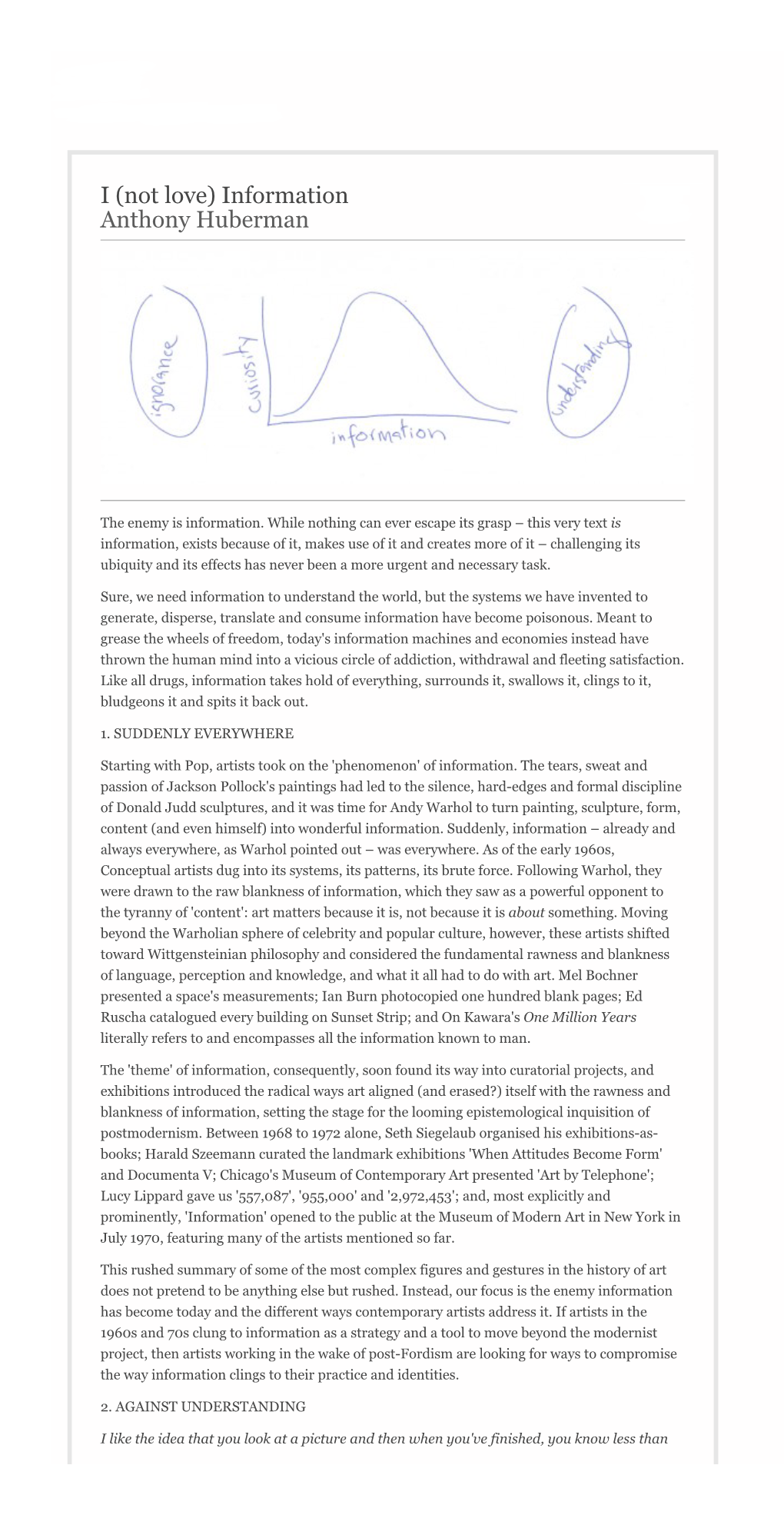

I (Not Love) Information 16 – Autumn/Winter 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Highland Games. Kilts Galore. Help: Graduating

THEFriday, October 10, 2014 - Volume 61.5 14049 Scenic Highway,BAGPIPE Lookout Mountain, Georgia, 30750 www.bagpipeonline.com Burning at Help: Graduating and the Stage Highland Games. Kilts Galore. Headed into Law BY KRISITE JAYA BY MARK MAKKAR Burning at the Stage took place Life after Covenant can either be on Thursday (10/3) night. The exciting or foreboding, but hear- Overlook was crowded with music ing from people who are already performances, friends huddling there always helps in lighting the around straw-bales, and marshmal- path that is to come. During the lows roasting atop fire pits. Alumni Law Career Panel, organized by who happened to be in town for the Center for Calling & Career, Homecoming contributed to the students listened to three Covenant festivities, exchanging squeals and alumni who have pursued work in hugs with familiar faces. The event, the field of law since graduating. according to the Senior Class Dr. Richard R. Follet introduced Cabinet member Sam Moreland, the meeting by stating that “Cov- “has taken different forms over the enant has a list of 60 graduates that years, but tends to have the ele- have gone into some kind of law ments of music, the Overlook, fire after graduating from Covenant.” and s’mores, and relaxed fellowship Three of them were able to make as commonalities.” it to the Panel. Josh Reif, John Many have long associated the Huisman, and Pete Johnson shared event with the Homecoming tradi- stories about when they were at tion, but Burning at the Stage is an BYGARRET SISSON Around 150 people attended was featured as the announcer. -

Physicality of the Analogue by Duncan Robinson BFA(Hons)

Physicality of the Analogue by Duncan Robinson BFA(Hons) Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. 2 Signed statement of originality This Thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, it incorporates no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. Duncan Robinson 3 Signed statement of authority of access to copying This Thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Duncan Robinson 4 Abstract: Inside the video player, spools spin, sensors read and heads rotate, generating an analogue signal from the videotape running through the system to the monitor. Within this electro mechanical space there is opportunity for intervention. Its accessibility allows direct manipulation to take place, creating imagery on the tape as pre-recorded signal of black burst1 without sound rolls through its mechanisms. The actual physical contact, manipulation of the tape, the moving mechanisms and the resulting images are the essence of the variable electrical space within which the analogue video signal is generated. In a way similar to the methods of the Musique Concrete pioneers, or EISENSTEIN's refinement of montage, I have explored the physical possibilities of machine intervention. I am working with what could be considered the last traces of analogue - audiotape was superseded by the compact disc and the videotape shall eventually be replaced by 2 digital video • For me, analogue is the space inside the video player. -

Press 1 April 2021 the Famous Artists Behind History's Greatest Album

CNN Style The famous artists behind history's greatest album covers Leah Dolan 1 April 2021 The famous artists behind history's greatest album covers Throughout the 20th-century record sleeves regularly served as canvases for some of the world's most famous artists. From Andy Warhol's electric yellow banana on the cover of The Velvet Underground & Nico's 1967's debut album, to the custom-sprayed Banksy street art that fronted Blur's 2003 "Think Tank," art has long been used to round out the listening experience. A new book, "Art Sleeves," explores some of the most influential, groundbreaking and controversial covers from the past forty years. "This is not a 'history of album art' type book," said the book's author, DJ and arts writer DB Burkeman over email. Instead, he says the book is a "love letter" to visual art and music culture. For the 45th anniversary of "The Velvet Underground & Nico" in 2012, British artist David Shrigley illustrated a special edition reissue cover for Castle Face Records. Image: David Shrigley/Rizzoli Featured records span genres and decades. Among them are Warhol's cover for The Rolling Stones' 1971 album "Sticky Fingers," featuring the now-famous close-up of a man's crotch (often assumed, incorrectly, to be frontman Mick Jagger in tight jeans) as well as an array of seminal covers designed by graphic designer Peter Saville, co-founder of influential Manchester-based indie label Factory Records. Despite having relatively little art direction experience under his belt, Saville was behind iconic covers such as Joy Division's "Unknown Pleasures" (1979), depicting the radio waves emitted by a rotating star, and the brimming basket of wilting roses -- a muted reproduction of a 1890 painting by French artist Henri Fantin-Latour -- that fronted New Order's "Power, Corruption & Lies" (1983). -

2006 TRASH Regionals Round 07 Tossups

2006 TRASH Regionals Round 07 Tossups 1. It appears twice in the e.e. cummings poem “little ladies more”. It also appears in the Tennessee Williams play A Streetcar Named Desire when Blanche DuBois asks it of Mitch. Seemingly awkward because of its use of the formal pronoun, it means, “Do you want to sleep with me (tonight)?” For ten points, give this phrase re-introduced to a new generation by Mya, Lil’ Kim, Pink, and Christina Aguilera in their 2001 version of “Lady Marmalade”. Answer: Voulez-vous coucher avec moi (ce soir)? 2. In Need for Speed: Most Wanted it’s called “Speed Breaker”, and is most often used to dodge roadblocks. In GUN, it’s called “Quick Draw.” The earliest example of it is probably in the 1980 Epyx game Rescue at Rigel. In Star Wars: Jedi Academy, you can get it using “Force Speed,” by killing Reborn Jedis, or typing the cheat code “there is no spoon.” For ten points, give the common name for the ability in video games to move at normal speed while the rest of the game is slowed down, most famously used in the Max Payne and, predictably, Matrix videogames. Answer: bullet time (Prompt on “slow motion” or equivalents. Note for itinerant cheaters: the cheat code is really “thereisnospoon”) 3. His favorite movie may be Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood, while he cried a lot when he paid to see Godfather III. His first name may be Marion, but his full name has also been reported to be William Williams. -

Rock of Ages Part 3 751 曲、合計時間:2:09:29:58 、3.16 GB

Rock of Ages part 3 751 曲、合計時間:2:09:29:58 、3.16 GB アーティスト アルバム 曲数 合計時間 21st Century Schizoid Band Live In Italy 1 7:06 808 State 24 Hour Party People 1 3:53 Adam F Colours 2 13:47 Future Soul 3 1 7:44 Afrika Bambaataa Dark Matter Moving At The Speed Of Light 1 5:02 Afrika Bambaataa Feat. Gary Numan & MC Chatt… Dark Matter Moving At The Speed Of Light 1 4:58 AFX Hangable Auto Bulb 2 9:57 Alan Parsons Project Eye In The Sky 1 7:18 Alice aLICE PERSONaL JUKE BOX 1 3:57 Viaggio in Italia 2 9:19 Amon Tobin (Cujo) Adventures In Foam 1 6:09 Andrea Bocelli Romanza 1 4:06 Sogno 1 4:44 Viaggio Italiano 1 3:13 Andrea Parker Kiss My Arp 2 11:13 Anekdoten From Within 3 15:36 Gravity 4 25:28 Nucleus (Remastered) 3 25:21 Vemod 4 30:34 Angela Aki Home 6 28:21 Kiss Me Good-Bye 2 10:03 Annie Haslam Annie Haslam 1 3:35 Annie Lennox Medusa 1 5:16 Anti Pop Consortium Tragic Epilogue 1 4:13 Aphex Twin ...I Care Because You Do 1 6:07 51/13 1 7:57 Classics 1 7:11 drukqs 3 5:17 drukqs (disc two) 3 4:58 Selected Ambient Works, Vol. II (Disc 1) 1 4:39 Apocalyptica Reflections 1 3:23 Apollo 440 Electro Glide in Blue 1 4:30 Aqualung Deep Blue 2 8:16 Arti E Mestieri Estrazioni 1 5:35 Asia Asia 2 8:39 Astor Piazzolla Piazzolla Original Soundtracks 1 4:49 The Balanescu Quartet Possessed 2 7:33 Band Aid 20 Do They Know It's Christmas? 1 5:07 Barratt Waugh I Love you, Goodbye 4 14:16 BEAT CRUSADERS SEXCITE 1 3:54 Beck Guero 1 3:22 Odelay 2 9:09 BEN FOLDS FIVE Reinhold Messner 1 3:23 Bice Cloudy Sky 1 4:00 Björk Homogenic 2 9:28 iTunes Originals - Björk 1 4:11 Bjork Selmasongs -

Connecting Time and Timbre Computational Methods for Generative Rhythmic Loops Insymbolic and Signal Domainspdfauthor

Connecting Time and Timbre: Computational Methods for Generative Rhythmic Loops in Symbolic and Signal Domains Cárthach Ó Nuanáin TESI DOCTORAL UPF / 2017 Thesis Director: Dr. Sergi Jordà Music Technology Group Dept. of Information and Communication Technologies Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Dissertation submitted to the Department of Information and Communication Tech- nologies of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR PER LA UNIVERSITAT POMPEU FABRA Copyright c 2017 by Cárthach Ó Nuanáin Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Music Technology Group (http://mtg.upf.edu), Department of Information and Communication Tech- nologies (http://www.upf.edu/dtic), Universitat Pompeu Fabra (http://www.upf.edu), Barcelona, Spain. III Do mo mháthair, Marian. V This thesis was conducted carried out at the Music Technology Group (MTG) of Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain, from Oct. 2013 to Nov. 2017. It was supervised by Dr. Sergi Jordà and Mr. Perfecto Herrera. Work in several parts of this thesis was carried out in collaboration with the GiantSteps team at the Music Technology Group in UPF as well as other members of the project consortium. Our work has been gratefully supported by the Department of Information and Com- munication Technologies (DTIC) PhD fellowship (2013-17), Universitat Pompeu Fabra, and the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program, as part of the GiantSteps project ((FP7-ICT-2013-10 Grant agreement no. 610591). Acknowledgments First and foremost I wish to thank my advisors and mentors Sergi Jordà and Perfecto Herrera. Thanks to Sergi for meeting me in Belfast many moons ago and bringing me to Barcelona. -

Music in His Own Image: the Aphex Twin Face

Nebula 1.1, June 2004 Music in His Own Image: The Aphex Twin Face. By Peter David Mathews Beyond the dark, intense vision of his music, a further disturbing dimension of Aphex Twin’s project is illuminated by his video clips. In particular, his two most famous videos, “Come to Daddy” and “Windowlicker,” are the fruit of collaborations with director Chris Cunningham; awards for “Come to Daddy” first brought both these artists into the mainstream eye in 1997. The outstanding feature of these clips is undoubtedly the face of Richard D. James. James, the man behind the Aphex Twin pseudonym, stares mockingly at the viewer, inevitably flashing his trademark leer. The unsettling characteristic of this smile is how the lips are stretched to the point of exaggeration. The initial impression of a broad, cheerful smile is quickly replaced by a feeling of incipient unease. Figure 1: Cover of Aphex Twin’s Richard D. James Album James’s grin becomes an inverted grimace, the tension of which is clearly visible in the creases around his eyes, nose and forehead. The look imbues these images with an intensity embellished by the fact that James’s expression never changes. Mathews: Music in His Own Image. 65 Nebula 1.1, June 2004 The initial impact of this look is augmented and intensified in several ways. The most obvious is through a process of multiplication. In each Aphex Twin clip, the secondary actors take on the face of their Creator. “Come to Daddy,” for instance, opens with an old woman walking her dog in a grimy, industrial setting. -

Social Spatialisation EXPLORING LINKS WITHIN CONTEMPORARY SONIC ART by Ben Ramsay

Social spatialisation EXPLORING LINKS WITHIN CONTEMPORARY SONIC ART by Ben Ramsay This article aims to briefly explore some the compositional links that exist between Intelligent Dance Music (IDM) and acousmatic music. Whilst the central theme of this article will focus on compositional links it will suggest some ways in which we might use these links to enhance pedagogic practice and widen access to acousmatic music. In particular, the article is concerned with documenting artists within Intelligent Dance Music (IDM), and how their practices relate to acousmatic music composition. The article will include a hand full of examples of music which highlight this musical exchange and will offer some ways to use current academic thinking to explain how IDM and acousmatics are related, at least from a theoretical point of view. There is a growing body of compositional work and theoretical research that draws from both acousmatics and various forms of electronic dance music. Much of this work blurs the boundaries of electronic music composition, often with vastly different aesthetic and cultural outcomes. Elements of acousmatic composition can be found scattered throughout Intelligent Dance Music (IDM) and on the other side of the divide there are a number of composers who are entering the world of acousmatics from a dance music background. This dynamic exchange of ideas and compositional processes is resulting in an interesting blend of music which is able to sit quite comfortably inside an academic framework as well as inside a more commercial one. Whilst there are a number of genres of dance music that could be described in terms of the theories that would normally relate to acousmatic music composition practices, the focus of this article lies particularly with Intelligent Dance Music. -

Byetone Raster-Noton Alemania

SÁBADO 2 DE MAYO Aphex Twin Rephlex / Warp Records UK Aphex Twin, AFX, The Tuss, Polygon Window, Caustic Window, The Dice Man…. múltiples nombres para un sólo hombre: Richard D. James, una de las figuras más influyentes e innovadoras de los últimos 25 años. Creció en Cornwall (Inglaterra) donde ya desde muy pequeño comenzó a demostrar sus capacidades con experimentos electrónicos llegando a ganar un premio escolar por tocar una melodía con un Spectrum y un televisor alterado. En 1991 fundó Rephlex Records y lanzó su primer trabajo, se mudó a Londres y comenzó una imparable carrera ascendente publicando material bajo sus innumerables alias tanto en Warp Records como Rephlex. Desde Selected Ambient Works hasta Druqks pasando por clásicos como Ventolin, Come to Daddy o la serie Analord. Un artista excéntrico y controvertido, un personaje influyente que ha trascendido en innumerables ocasiones los límites del underground electrónico a base de trabajo y genialidades. Sus colaboraciones con el también genial Chris Cuningham nos han brindado algunos de los mejores trabajos audiovisuales hasta la fecha: Windowlicker, Come To Daddy o Rubber Johnny son algunas de las obras donde se ponen al descubierto sus locuras y cualidades. Acid, IDM, techno, ambient…. son algunos de los géneros que Aphex Twin domina a la perfección y en los que ha jugado y juega un papel fundamental como evolucionador y visionario. Rodeado por multitud de leyendas, con una perfección milimétrica en el dominio de viejos sintetizadores y la creación de nuevos sonidos y dotado de una de las mentes más inquietas y creativas que existen en la escena musical, Aphex Twin sigue creando, a día de hoy, registros en las fronteras de las normas aceptadas de la música. -

Exploring Compositional Relationships Between Acousmatic Music and Electronica

Exploring compositional relationships between acousmatic music and electronica Ben Ramsay Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University Leicester 2 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 5 DVD contents ........................................................................................................................ 6 CHAPTER 1 ......................................................................................................................... 8 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 8 1.0.1 Research imperatives .......................................................................................... 11 1.0.2 High art vs. popular art ........................................................................................ 14 1.0.3 The emergence of electronica ............................................................................. 16 1.1 Literature Review ......................................................................................................... 18 1.1.1 Materials .............................................................................................................. 18 1.1.2 Spaces ................................................................................................................. -

Experiencing the Films of Chris Cunningham

I Want Your Soul: Experiencing The Films Of Chris Cunningham William Hughes – 26/06/2017 Student Number: 11312882 Media Studies: Film Studies MA Supervisor: Tarja Laine Second Reader: Emiel Martens 1 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................................... 6 The Visceral ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 24 The Uncanny and The Sublime ........................................................................................................ 25 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 44 Black Humour and the Absurd ......................................................................................................... 45 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................... 59 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................ 60 Bibliography .................................................................................................................................... -

Aphex Twin ...I Care Because You Do Mp3, Flac, Wma

Aphex Twin ...I Care Because You Do mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: ...I Care Because You Do Country: US Released: 1995 Style: Techno, IDM, Acid, Experimental, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1546 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1278 mb WMA version RAR size: 1694 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 543 Other Formats: MP3 MOD WMA AHX MP4 ASF AAC Tracklist 1 Acrid Avid Jam Shred 7:38 2 The Waxen Pith 4:49 3 Wax The Nip 4:18 4 Icct Hedral (Edit) 6:07 5 Ventolin (Video Version) 4:29 6 Come On You Slags! 5:44 7 Start As You Mean To Go On 6:05 8 Wet Tip Hen Ax 5:17 9 Mookid 3:51 10 Alberto Balsalm 5:10 11 Cow Cud Is A Twin 5:33 12 Next Heap With 4:43 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sire Records Company Phonographic Copyright (p) – WEA International Inc. Copyright (c) – Sire Records Company Copyright (c) – WEA International Inc. Distributed By – Elektra Entertainment Group Pressed By – Specialty Records Corporation Manufactured By – WEA Manufacturing Credits Producer, Written-By, Artwork [Self Portrait By Me] – Richard D. James Notes ℗© 1995 Sire Records Company, for the United States and WEA International for the world outside of the United States, excluding Europe. Track title anagrams (not mentioned on the release): 1. Acrid Avid Jam Shred = Richard David James 2. The Waxen Pith = The Aphex Twin 3. Wax The Nip = Aphex Twin 11. Cow Cud Is A Twin = Caustic Window 12. Next Heap With = The Aphex Twin Comes in a Warner Bros.