Byzantine Studies Conference 2015 New York, October 22-25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visualizing the Byzantine City the Art of Memory

Abstracts Visualizing the Byzantine City Charalambos Bakirtzis Depictions of cities: in the icon “Allegory of Jerusalem on High,” two cities are depicted, one in the foothills and the other at the edge of a rocky mountain. The lengthy inscription of the icon is of interest from a town-planning and architectural standpoint. The imperial Christian city: in the mosaics of the Rotunda in Thessalonike, the city is not shown with walls, but with palaces and other splendid public buildings, declaring the emperor’s authority as the sole ruler and guarantor of the unity of the state and the well-being of cities, which was replaced by the authority of Christ. The appearance of the walled city: all the events shown in the mosaics (seventh century) of the basilica of St. Demetrios are taking place outside the walls of the city, probably beside the roads that lead to it. The city’s chora not only protected the city; it was also protected by it. A description of the city/kastron: John Kameniates lived through the capture of Thessalonike by the Arabs in the summer of 904. At the beginning of the narrative, he prefixes a lengthy description/encomium of Thessalonike. The means of approaching the place indicate that the way the city is described by Kameniates suits a visual description. Visualizing the Late Byzantine city: A. In an icon St. Demetrios is shown astride a horse. In the background, Thessalonike is depicted from above. A fitting comment on this depiction of Thessalonike is offered by John Staurakios because he renders the admiration called forth by the large Late Byzantine capitals in connection with the abandoned countryside. -

1 Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1St

Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1st January 2020 Holy Name of Jesus Circumcision of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea of Palestine, Father of the Church (379) Beoc of Lough Derg, Donegal (5th or 6th c.) Connat, Abbess of St. Brigid’s convent at Kildare, Ireland (590) Ossene of Clonmore, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 3:10-19 Eph 3:1-7 Lk 6:5-11 Holy Name of Jesus: ♦ Vespers: Ps 8 and 19 ♦ 1st Nocturn: Ps 64 1Tm 2:1-6 Lk 6:16-22 ♦ 3rd Nocturn: Ps 71 and 134 Phil 2:6-11 ♦ Matins: Jn 10:9-16 ♦ Liturgy: Gn 17:1-14 Ps 112 Col 2:8-12 Lk 2:20-21 ♦ Sext: Ps 53 ♦ None: Ps 148 1 Thursday 2 January 2020 Seraphim, priest-monk of Sarov (1833) Adalard, Abbot of Corbie, Founder of New Corbie (827) John of Kronstadt, priest and confessor (1908) Seiriol, Welsh monk and hermit at Anglesey, off the coast of north Wales (early 6th c.) Munchin, monk, Patron of Limerick, Ireland (7th c.) The thousand Lichfield Christians martyred during the reign of Diocletian (c. 333) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:1-6 Eph 3:8-13 Lk 8:24-36 Friday 3 January 2020 Genevieve, virgin, Patroness of Paris (502) Blimont, monk of Luxeuil, 3rd Abbot of Leuconay (673) Malachi, prophet (c. 515 BC) Finlugh, Abbot of Derry (6th c.) Fintan, Abbot and Patron Saint of Doon, Limerick, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:7-14a Eph 3:14-21 Lk 6:46-49 Saturday 4 January 2020 70 Disciples of Our Lord Jesus Christ Gregory, Bishop of Langres (540) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:14b-20 Eph 4:1-16 Lk 7:1-10 70 Disciples: Lk 10:1-5 2 Sunday 5 January 2020 (Forefeast of the Epiphany) Syncletica, hermit in Egypt (c. -

Russian Orthodoxy and Women's Spirituality In

RUSSIAN ORTHODOXY AND WOMEN’S SPIRITUALITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA* Christine D. Worobec On 8 November 1885, the feast day of Archangel Michael, the Abbess Taisiia had a mystical experience in the midst of a church service dedicated to the tonsuring of sisters at Leushino. The women’s religious community of Leushino had recently been ele vated to the status of a monastery.1 Conducting an all-women’s choir on that special day, the abbess became exhilarated by the beautiful refrain of the Cherubikon hymn, “Let us lay aside all earthly cares,” and envisioned Christ surrounded by angels above the iconostasis. She later wrote, “Something was happening, but what it was I am unable to tell, although I saw and heard every thing. It was not something of this world. From the beginning of the vision, I seemed to fall into ecstatic rapture Tears were stream ing down my face. I realized that everyone was looking at me in astonishment, and even fear....”2 Five years later, a newspaper columnistwitnessedasceneinachurch in the Smolensk village of Egor'-Bunakovo in which a woman began to scream in the midst of the singing of the Cherubikon. He described “a horrible in *This book chapter is dedicated to the memory of Brenda Meehan, who pioneered the study of Russian Orthodox women religious in the modern period. 1 The Russian language does not have a separate word such as “convent” or nunnery” to distinguish women’s from men’s monastic institutions. 2 Abbess Thaisia, 194; quoted in Meehan, Holy Women o f Russia, 126. Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture. -

TYPIKON (Arranged by Rev

TYPIKON (Arranged by Rev. Taras Chaparin) March 2016 Sunday, March 26 4th Sunday of Great Lent Commemoration of Saint John of the Ladder (Climacus). Synaxis of the Holy Archangel Gabriel. Tone 4. Matins Gospel I. Liturgy of St. Basil the Great. Bright vestments. Resurrection Tropar (Tone 4); Tropar of the Annunciation; Tropar of St. John (4th Sunday); Glory/Now: Kondak of the Annunciation; Prokimen, Alleluia Verses of Resurrection (Tone 4) and of the Annunciation. Irmos, “In You, O Full of Grace…” Communion Hymn of Resurrection and of the Annunciation. Scripture readings for the 4th Sunday of Lent: Epistle: Hebrew §314 [6:13-20]. Gospel: Mark §40 [9:17-31]. In the evening: Lenten Vespers. Monday, March 27 Our Holy Mother Matrona of Thessalonica. Tuesday, March 28 Our Venerable Father Hilarion the New; the Holy Stephen, the Wonderworker (464). Wednesday, March 29 Our Venerable Father Mark, Bishop of Arethusa; the Deacon Cyril and Others Martyred during the Reign of Julian the Apostate (360-63). Dark vestments. Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. Scripture readings for the 5th Wednesday of Lent: Genesis 17:1-9; Proverbs 15:20-16:9. Thursday, March 30 Our Venerable Father John Climacus, Author of The Ladder of Divine Ascent (c. 649). Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete. Friday, March 31 Our Venerable Father Hypatius, Bishop of Gangra (312-37). Dark vestments. Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. Scripture readings for the 5th Friday of Lent: Genesis 22:1-18; Proverbs 17:17-18:5. April 2016 Saturday, April 1 5th Saturday of Lent – Saturday of the Akathist Hymn Our Venerable Mother Mary of Egypt (527-65). -

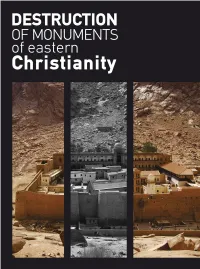

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

9781107404748 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-40474-8 - John Skylitzes: A Synopsis of Byzantine History, 811–1057 John Wortley Index More information Index Aaron, brother-in-law of Isaac I Komnenos , A n a t o l i a , Aaron, son of John Vladisthlav , A n a t o l i k o n , , , , , , , , , , , , A b e l b a k e s , , , , , , , , , , , A b o u l c h a r e , , , , , , , A b o u z a c h a r , Andrew the Scyth , A b r a m , , , Andrew the stratelates , , A b r a m i t e s , m o n a s t e r y o f t h e , A n d r o n i k o s D o u k a s , , A b u H a f s , , , , A n e m a s , , , A b y d o s , , , , , , , , , , A n i , , , , , , , , , , , A n n a , s i s t e r o f B a s i l I I , x i , x x x i , , , , , A d r i a n , , , , , , , , , , , A d r i a n o p l e , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , A n t h e m i o s , m o n a s t e r y a t , , , , Anthony Kauleas, patriarch , , A e t i o s , Anthony the Stoudite, patriarch , A f r i c a , , , , , , , , , , A n t i g o n u s , d o m e s t i c o f t h e s c h o l a i , , , , , A n t i g o n o s , s o n o f B a r d a s , , A g r o s , m o n a s t e r y , A n z e s , , A i k a t e r i n a d a u g h t e r o f V l a d i s t h l a v , Aplesphares, ruler of Tivion -

Constructing the Underground Community: the Letters of Theodore the Studite and the Letter of Emperors Michael Ii and Theophilos to Louis the Pious

Vladimir Baranov Novosibirsk, Russia [email protected] CONSTRUCTING THE UNDERGROUND COMMUNITY: THE LETTERS OF THEODORE THE STUDITE AND THE LETTER OF EMPERORS MICHAEL II AND THEOPHILOS TO LOUIS THE PIOUS The Le er of the Iconoclastic Emperors Michael II and Theophilos to Louis the Pious1 (dated to 824) contains a list of off ences that were allegedly commi ed by the Iconodules against what they considered the right practices of the Church. Their list includes the substitution of images in churches for crosses, taking images as godparents, using images to perform the cu ing of children’s hair and monastic habit, scraping paint of images to be added to the Eucharist or distributing the Eucharistic bread from the hands of images, as well as using panel images as altars for serving the Liturgy in ordinary houses and church- es.2 Of course, these might have been easily treated as fi ction and pro- (1) Emperor Theophilus (b. 812/813) was crowned co-Emperor in 821 by his Father Michael II (820–829), and this is why his name appears on the Let- ter. However, since in 824 he was only a 12-year old boy, for the Le er I will use the short title “Le er of Michael II.” (2) The Le er is preserved in the MGH, Leg. Sect. III, Concilia, tomus II, pars 2, Concilia aevi Karolini I (Hannover—Leipzig, 1908, repr. 1979) 475–480; Mansi, XIV, 417–422; the pertinent passage is translated in C. Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312–1453: Sources and Documents (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986) 157–158. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Bourbouhakis Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Emmanuel C. Bourbouhakis Assistant Professor Department of Classics Princeton University 141 East Pyne Princeton, NJ 08544 Tel: 609-258-3951 Email: [email protected] Current Position 2011- Assistant Professor, Department of Classics, Princeton University Previous Employment 2008-2010 DFG Teaching–Research Fellow, Department of History, Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg 2007-2008 Lecturer, Department of the Classics, Harvard University Education 09/1999-10/2006 PhD in Classical and Byzantine Philology, Harvard University 09/1997-06/1999 MA in Classical Philology, University of Western Ontario 09/1989-06/1993 BA in History, McGill University; Liberal Arts College, Concordia University Ancient Languages Latin, Greek (classical & medieval) Modern Languages Greek (modern), English, French, German, Italian Awards, Honours, Fellowships 2010 Gerda Henkel Stiftung Fellowship 2008 Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Forschungsstipendium (German National Research Foundation Fellowship) at the Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg 2005 Harvard University Humanities Dissertation Fellowship 2004 Dumbarton Oaks Junior Fellowship 2003 DAAD Doctoral Fellowship at the Byzantinisch-Neugriechisches Institut, Freie Universität Berlin 2 2002 Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Grant Academic Service Princeton University 2011-2012 Search Committee, Byzantine Art and Archaeology 2012-2013 Forbes College Academic Advisor 2012-2013 Department of Classics Seniors Adviser 2012-2013 Department of Classics Undergraduate -

A Byzantine Christmas

VOCAL ENSEMBLE 26th Annual Season October 2017 Tchaikovsky: All-Night Vigil October 2017 CR Presents: The Byrd Ensemble November 2017 Arctic Light II: Northern Exposure December 2017 A Byzantine Christmas January 2018 The 12 Days of Christmas in the East February 2018 Machaut Mass with Marcel Pérès March 2018 CR Presents: The Tudor Choir March 2018 Ivan Moody: The Akáthistos Hymn April 2018 Venice in the East A Byzantine Christmas: Sun of Justice 1 What a city! Here are just some of the classical music performances you can find around Portland, coming up soon! JAN 11 | 12 FEB 10 | 11 A FAMILY AFFAIR SOLO: LUKÁŠ VONDRÁCˇEK, pianist Spotlight on cellist Marilyn de Oliveira Chopin, Smetana, Brahms, Scriabin, Liszt with special family guests! PORTLANDPIANO.ORG | 503-228-1388 THIRDANGLE.ORG | 503-331-0301 FEB 16 | 17 | 18 JAN 13 | 14 IL FAVORITO SOLO: SUNWOOK KIM, pianist Violinist Ricardo Minasi directs a We Love Our Volunteers! Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, Schubert program of Italy’s finest composers. n tns to our lol volunteers o serve s users ste re o oe ersonnel osts PORTLANDPIANO.ORG | 503-228-1388 PBO.ORG | 503-222-6000 or our usns or n ottee eers n oe ssstnts Weter ou re ne to JAN 15 | 16 FEB 21 us or ou ve een nvolve sne te ennn tn ou or our otent n nness TAKÁCS QUARTET MIRÓ QUARTET WITH JEFFREY KAHANE “The consummate artistry of the Takács is Co-presented by Chamber Music Northwest ou re vlue rt o te O l n e re rteul simply breathtaking” The Guardian and Portland’5 Centers for the Arts FOCM.ORG | 503-224-9842 CMNW.ORG | 503-294-6400 JAN 26-29 FEB 21 WINTER FESTIVAL: CONCERTOS MOZART WITH MONICA Celebrating Mozart’s 262nd birthday, Baroque Mozart and Michael Haydn string quartets DEC 20 concertos, and modern concertos performed by Monica Huggett and other PDX VIVALDI’S MAGNIFICAT AND GLORIA CMNW.ORG | 503-294-6400 favorites. -

HYMNS of KASSIANÍ on April 16Th Cappella Records Is Proud to Present the Release of Hymns of Kassianí Performed by Cappella Romana, Alexander Lingas, Music Director

New release by Cappella Romana The earliest music by a female composer HYMNS OF KASSIANÍ On April 16th Cappella Records is proud to present the release of Hymns of Kassianí performed by Cappella Romana, Alexander Lingas, music director. Discover the world’s earliest music by a female composer: 9th-century nun, poet, and hymnographer Kassianí (Kassía). The same men and women of Cappella Romana who brought you the Naxos of America -‐ New Release Submission Handbook V1.0 9 Lost Voices of Hagia Sophia bestseller (43 weeks on Billboard), now sing the earliest music we have by a female composer, including long- suppressed hymns recorded here for the first time. They close with two medieval versions of her beloved hymn for Orthodox Holy Week (Orthodox Easter in 2021 is May 2nd). Cappella Romana is the world’s leading ensemble in the field of medieval Byzantine chant. Building on its extensive catalogue of this repertoire, Hymns of Kassianí is its 25th release. This is the first of a planned series to record all of Kassianí’s surviving works. SALES POINTS • The earliest music by a female composer, three centuries before THIS IS AN EXAMPLE OF A TYPICAL ONE SHEET. Hildegard von Bingen. Label You do not need to follow this exact layout, but please include as much of Logo this information as possible in your sales sheet and submit it to • Ecstatic, never-before recorded works for Christmas and Lent Naxos of America. • Illuminated by the latest research on historically informed RELEASE DATE: 4/16/2021 performance of medieval Byzantine chant. • In high-res for downloads, multi-channel surround sound, produced by multi-GRAMMY® Award winner Blanton Alspaugh and the team at Soundmirror (100+ GRAMMY® nominations and awards). -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Methodios I patriarch of Constantinople: churchman, politician and confessor for the faith Bithos, George P. How to cite: Bithos, George P. (2001) Methodios I patriarch of Constantinople: churchman, politician and confessor for the faith, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4239/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 METHODIOS I PATRIARCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE Churchman, Politician and Confessor for the Faith Submitted by George P. Bithos BS DDS University of Durham Department of Theology A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Orthodox Theology and Byzantine History 2001 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including' Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent All information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately.