Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kejriwal-Ki-Kahani-Chitron-Ki-Zabani

केजरवाल के कम से परेशां कसी आम आदमी ने उनके ीमखु पर याह फेकं. आम आदमी पाट क सभाओं म# काय$कता$ओं से &यादा 'ेस वाले होते ह). क*मीर +वरोधी और भारत देश को खं.डत करने वाले संगठन2 का साथ इनको श5ु से 6मलता रहा है. Shimrit lee वो म8हला है िजसके ऊपर शक है क वो सी आई ए एज#ट है. इस म8हला ने केजरवाल क एन जी ओ म# कु छ 8दन रह कर भारत के लोकतं> पर शोध कया था. िजंदल ?पु के असल मा6लक एस िजंदल के साथ अAना और केजरवाल. िजंदल ?पु कोयला घोटाले म# शा6मल है. ये है इनके सेकु लCर&म का असल 5प. Dया कभी इAह# साध ू संत2 के साथ भी देखा गया है. मिलमु वोट2 के 6लए ये कु छ भी कर#गे. दंगे के आरो+पय2 तक को गले लगाय#गे. योगेAF यादव पहले कां?ेस के 6लए काम कया करते थे. ये पहले (एन ए सी ) िजसक अIयJ सोKनया गाँधी ह) के 6लए भी काम कया करते थे. भारत के लोकसभा चनावु म# +वदे6शय2 का आम आदमी पाट के Nवारा दखल. ये कोई भी सकते ह). सी आई ए एज#ट भी. केजरवाल मलायमु 6संह के भी बाप ह). उAह# कु छ 6सरफरे 8हAदओंु का वोट पDका है और बाक का 8हसाब मिलमु वोट से चल जायेगा. -

Telangana State Election Commission

TELANGANA STATE ELECTION COMMISSION Recognized National Political Parties Sl. Symbols in Symbols Name of the Political Party No. English / Telugu Reserved Elephant 1 Bahujan Samaj Party ఏనుగు Lotus 2 Bharatiya Janata Party కమలం Ears of Corn & Sickle 3 Communist Party of India కంకి కొడవ젿 Hammer, Sickle & Star 4 Communist Party of India (Marxist) సుత్తి కొడవ젿 నక్షత్రం Hand 5 Indian National Congress చెయ్యి Clock 6 Nationalist Congress Party గడియారము Recognized State Parties in the State of Telangana Sl. Symbols in Name of the Party Symbols Reserved No. English / Telugu All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul- Kite 1 Muslimeen గా젿 పటం Car 2 Telangana Rastra Samithi కారు Bicycle 3 Telugu Desam Party స ైకిలు Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Ceiling Fan 4 Congress Party పంఖా Recognised State Parties in other States Sl. Symbols in Symbols Name of the Political Party No. English / Telugu Reserved Two Leaves All India Anna Dravida Munnetra 1 Kazhagam ర ండు ఆకులు Lion 2 All India Forward Bloc స ంహము A Lady Farmer 3 Janata Dal (Secular) Carrying Paddy వరి 롋పుతో ఉనన మహిళ Arrow 4 Janata Dal (United) బాణము Hand Pump 5 Rastriya Lok Dal చేత్త పంపు Banyan Tree 6 Samajwadi Party మరిి చెటటు Registered Political Parties with reserved symbol - NIL - TELANGANA STATE ELECTION COMMISSION Registered Political Parties without Reserved Symbol Sl. No. Name of the Political Party 1 All India Stree Shakthi Party 2 Ambedkar National Congress 3 Bahujan Samj Party (Ambedkar – Phule) 4 BC United Front Party 5 Bharateeya Bhahujana Prajarajyam 6 Bharat Labour Party 7 Bharat Janalok Party 8 -

Secrets of RSS

Secrets of RSS DEMYSTIFYING THE SANGH (The Largest Indian NGO in the World) by Ratan Sharda © Ratan Sharda E-book of second edition released May, 2015 Ratan Sharda, Mumbai, India Email:[email protected]; [email protected] License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-soldor given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person,please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and didnot purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to yourfavorite ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hardwork of this author. About the Book Narendra Modi, the present Prime Minister of India, is a true blue RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteers Organization) swayamsevak or volunteer. More importantly, he is a product of prachaarak system, a unique institution of RSS. More than his election campaigns, his conduct after becoming the Prime Minister really tells us how a responsible RSS worker and prachaarak responds to any responsibility he is entrusted with. His rise is also illustrative example of submission by author in this book that RSS has been able to design a system that can create ‘extraordinary achievers out of ordinary people’. When the first edition of Secrets of RSS was released, air was thick with motivated propaganda about ‘Saffron terror’ and RSS was the favourite whipping boy as the face of ‘Hindu fascism’. Now as the second edition is ready for release, environment has transformed radically. -

Groundwater Quality Assessment for Irrigation Use in Vadodara District, Gujarat, India S

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Vol:7, No:7, 2013 Groundwater Quality Assessment for Irrigation Use in Vadodara District, Gujarat, India S. M. Shah and N. J. Mistry Savli taluka of Vadodara district. People of this district are the Abstract—This study was conducted to evaluate factors pioneer users of shallow and deep tube wells for drinking and regulating groundwater quality in an area with agriculture as main irrigation Purpose. use. Under this study twelve groundwater samples have been collected from Padra taluka, Dabhoi taluka and Savli taluka of Vadodara district. Groundwater samples were chemically analyzed II. STUDY AREA for major physicochemical parameter in order to understand the Vadodara is located at 22°18'N 73°11'E / 22.30°N 73.19°E different geochemical processes affecting the groundwater quality. in western India at an elevation of 39 meters (123 feet). It has The analytical results shows higher concentration of total dissolved the area of 148.95 km² and a population of 4.1 million solids (16.67%), electrical conductivity (25%) and magnesium (8.33%) for pre monsoon and total dissolved solids (16.67%), according to the 2010-11 censuses. The city sites on the banks electrical conductivity (33.3%) and magnesium (8.33%) for post of the River Vishwamitri, in central Gujarat. Vadodara is the monsoon which indicates signs of deterioration as per WHO and BIS third most populated city in the Indian, State of Gujarat after standards. On the other hand, 50% groundwater sample is unsuitable Ahmadabad and Surat. -

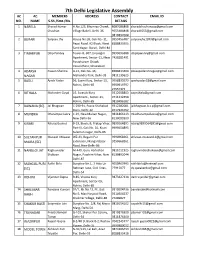

List of MLA Contact Details

7th Delhi Legislative Assembly AC AC MEMBERS ADDRESS CONTACT EMAIL ID NO. NAME S.Sh./Smt./Ms. DETAILS 1 NARELA Sharad Kumar H.No.123, Bhumiya Chowk, 8687686868 [email protected] Chauhan Village Bakoli, Delhi-36 9555484848 [email protected] 9818892004 2 BURARI Sanjeev Jha House No.09, Gali No.-11, 9953456787 [email protected] Pepsi Road, A2 Block, West 8588833505 Sant Nagar, Burari, Delhi-84 3 TIMARPUR Dilip Pandey Tower-B, 607, Dronagiri 9999696388 [email protected] Apartment, Sector-11, Near 7428281491 Parashuram Chowk Vasundhara, Ghaziabad 4 ADARSH Pawan Sharma A-13, Gali No.-36, 8588833404 [email protected] NAGAR Mahendra Park, Delhi-33 9811139625 5 BADLI Ajesh Yadav 56, Laxmi Kunj, Sector-13, 9958833979 [email protected] Rohini, Delhi-85 9990919797 27557375 6 RITHALA Mohinder Goyal 19, Swastik Kunj 9312658803 [email protected] Apartment., Sector-13, 9711332458 Rohini, Delhi-85 9810496182 7 BAWANA (SC) Jai Bhagwan C-290-91, Pucca Shahabad 9312282081 [email protected] Dairy, Delhi-42 9717921052 8 MUNDKA Dharampal Lakra C-29, New Multan Nagar, 9811866113 [email protected] New Delhi-56 8130099300 9 KIRARI Rituraj Govind B-19, Block,-B, Pratap Vihar, 9899564895 [email protected] Part-III, Gali No. 10, Kirari 9999654895 Suleman nagar, Delhi-86 10 SULTANPUR Mukesh Ahlawat WZ-43, Begum Pur 9990968261 [email protected] MAJRA (SC) Extension, Mangal Bazar 9250668261 Road, New Delhi-86 11 NANGLOI JAT Raghuvinder M-449, Guru Harkishan 9811011925 [email protected] -

Madhya Gujarat Vij Company Limited Name Designation Department Email-Id Contact No Mr

Madhya Gujarat Vij Company Limited Name Designation Department email-id Contact No Mr. Rajesh Manjhu,IAS Managing Director Corporate Office [email protected] 0265-2356824 Mr. K R Shah Sr. Chief General Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200651 Mr. THAKORPRASAD CHANDULAL CHOKSHI Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9879202415 Mr. K N Parikh Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200737 Mr. Mayank G Pandya General Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200689 Mr. KETAN M ANTANI Company Secretary Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200693 Mr. H R Shah Additional Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208253 Mr. M T Sanghada Additional Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208277 Mr. P R RANPARA Additional General Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9825083901 Mr. V B Gandhi Additional Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208141 Mr. BHARAT J UPADHYAY Additional Chief Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208224 Mr. S J Shukla Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200911 Mr. M M Acharya Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208282 Mr. Chandrakant N Pendor Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208799 Mr. Jatin Jayantilal Parikh Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200639 Mr. BIHAG C MAJMUDAR Superintending Engineer Corporate Office [email protected] 9925209512 Mr. Paresh Narendraray Shah Chief Finance Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9825603164 Mr. Harsad Maganbhai Patel Controller of Accounts Corporate Office [email protected] 9925208189 Mr. H. I. PATEL Deputy General Manager Corporate Office [email protected] 9879200749 Mr. -

Sub-Basalt Imaging in Padra Field, South Cambay Basin, India Through Sub-Surface Angle Domain Processing Abhinandan Ghosh1*, Debkumar Chatterjee1 and C.P.S

Sub-basalt imaging in Padra Field, South Cambay Basin, India through sub-surface angle domain processing Abhinandan Ghosh1*, Debkumar Chatterjee1 and C.P.S. Rana1 1SPIC, GPS, WOB, ONGC, Mumbai *[email protected] Abstract Penetration of seismic energy below basalt and generation of sub-basalt imaging has always been a challenging task for seismic exploration. Strong inter-bed multiples always mask the weak reflections coming from sub-basalt formations. Severe scattering of seismic energy due to heterogeneity of basalt layer further complicates the problem which results in the lowering of frequency content of the data and also velocity model building for imaging becomes highly challenging. Padra Field in South Cambay Basin, India is no different, where basaltic Deccan Trap is the technical basement. Conventional PSTM vintages of this area imaged shallow sedimentary part only without much success in imaging the sub-basalt part. These challenges have been addressed and successful sub-basalt imaging is being achieved through full azimuth sub- surface angle domain processing. In this paper we describe a workflow designed to better image the basement, and fine scale features within the basement, at Padra Field. Introduction Sub-basalt imaging continues to provide a challenge in the Padra area. The ability to image seismically the subsurface below the basalts is limited by the fact that basaltic layers are characterized by the poor penetration because of high reflectivity contrasts at the top of the basalt and also due to intra basalt discontinuities, attenuation and strong internal scattering of seismic energy due to heterogeneity of basalt layer resulting lowering of the frequency content of the seismic data. -

Ambedkar and the Dalit Buddhist Movement in India (1950- 2000)

International Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 2 Issue 6 ǁ July 2017. www.ijahss.com Ambedkar and The Dalit Buddhist Movement in India (1950- 2000) Dr. Shaji. A Faculty Member, Department of History School of Distance Education University of Kerala, Palayam, Thiruvananthapuram Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar was one of the most remarkable men of his time, and the story of his life is the story of his exceptional talent and outstanding force of character which helped him to succeed in overcoming some of the most formidable obstacles that an unjust and oppressive society has ever placed in the way of an individual. His contribution to the cause of Dalits has undoubtedly been the most significant event in 20th century India. Ambedkar was a man whose genius extended over diverse issues of human affairs. Born to Mahar parents, he would have been one of the many untouchables of his times, condemned to a life of suffering and misery, had he not doggedly overcome the oppressive circumstances of his birth to rise to pre-eminence in India‘s public life. The centre of life of Ambedkar was his devotion to the liberation of the backward classes and he struggled to find a satisfactory ideological expression for that liberation. He won the confidence of the- untouchables and became their supreme leader. To mobilise his followers he established organisations such as the Bahishkrit Hitkarni Sabha, Independent Labour Party and later All India Scheduled Caste Federation. He led a number of temple-entry Satyagrahas, organized the untouchables, established many educational institutions and propagated his views through newspapers like the 'Mooknayak', 'Bahishkrit Bharat' and 'Janata'. -

Political Parties in India

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Political Parties in India India has very diverse multi party political system. There are three types of political parties in Indiai.e. national parties (7), state recognized party (48) and unrecognized parties (1706). All the political parties which wish to contest local, state or national elections are required to be registered by the Election Commission of India (ECI). A recognized party enjoys privileges like reserved party symbol, free broadcast time on state run television and radio in the favour of party. Election commission asks to these national parties regarding the date of elections and receives inputs for the conduct of free and fair polls National Party: A registered party is recognised as a National Party only if it fulfils any one of the following three conditions: 1. If a party wins 2% of seats in the Lok Sabha (as of 2014, 11 seats) from at least 3 different States. 2. At a General Election to Lok Sabha or Legislative Assembly, the party polls 6% of votes in four States in addition to 4 Lok Sabha seats. 3. A party is recognised as a State Party in four or more States. The Indian political parties are categorized into two main types. National level parties and state level parties. National parties are political parties which, participate in different elections all over India. For example, Indian National Congress, Bhartiya Janata Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Samajwadi Party, Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist) and some other parties. State parties or regional parties are political parties which, participate in different elections but only within one 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE state. -

Emplacing and Excavating the City: Art, Ecology, and Public Space in New Delhi

Transcultural Studies 2015.1 75 Emplacing and Excavating the City: Art, Ecology, and Public Space in New Delhi Christiane Brosius, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Every claim on public space is a claim on the public imagination. It is a response to the questions: What can we imagine together?… Are we, in fact, a collective; is the collective a site for the testing of alternatives, or a ground for mobilising conformity? (Adajania 2008) Introduction Contemporary art production can facilitate the study of a city’s urban fabric, its societal change, and its cultural meaning production; this is particularly the case when examining exhibition practices and questions of how, why, when, where, and by whom artworks came to be emplaced and connected to certain themes and concepts.* Emplacement here refers to the process of constructing space for certain events or activities that involve sensory and affective aspects (Burrell and Dale 2014, 685). Emplacing art thus concerns a particular and temporary articulation of and in space within a relational set of connections (rather than binaries). In South Asia, where contemporary “fine art”1 is still largely confined to enclosed spaces like the museum or the gallery, which seek to cultivate a “learned” and experienced audience, the idea of conceptualising art for and in rapidly expanding and changing cities like Delhi challenges our notions of place, publicness, and urban development. The particular case discussed here, the public art festival, promises—and sets out—to explore an alternative vision of the city, alternative aspirations towards “belonging to and participating in” it.2 Nancy Adajania’s question “What can we imagine together” indirectly addresses which repositories and languages are available and can be used for such a joint effort, and who should be included in the undertaking. -

Revista Humania Diciembre 2017 FINAL.Indd

Humania del Sur. Año 12, Nº 23. Julio-Diciembre, 2017. Santosh I. Raut Liberating India: Contextualising nationalism, democracy, and Dr. Ambedkar... pp. 65-91. Liberating India: Contextualising nationalism, democracy, and Dr. Ambedkar Santosh I. Raut EFL University, Hyderabad, India. santoshrautefl @gmail.com Abstract Dr. B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956) the principal architect of the Indian constitution, and one of the most visionary leaders of India. He is the father of Indian democracy and a nation-builder that shaped modern India. His views on religion, how it aff ects socio-political behaviour, and therefore what needs to build an egalitarian society are unique. Th erefore, this paper attempts to analyse Ambedkar’s vision of nation and democracy. What role does religion play in society and politics? Th is article also envisages to studies how caste-system is the major barrier to bring about a true nation and a harmonious society. Keywords: India, B. R. Ambedkar, national constructor, nationalism and democracy, caste system, egalitarian society. Liberación de la India: Contextualizando el nacionalismo, la democracia y el Dr. Ambedkar Resumen Dr. B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956), el principal arquitecto de la constitución india, y uno de los líderes más visionarios de la India. Él es el padre de la democracia india y el constructor de la nación que dio forma a la India moderna. Su punto de vista sobre la religión, cómo afecta el comportamiento sociopolítico y, por lo tanto, lo que necesita construir una sociedad igualitaria son únicos. Este documento intenta analizar la visión de nación y democracia de Ambedkar. ¿Qué papel juega la religión en la sociedad y en la política?. -

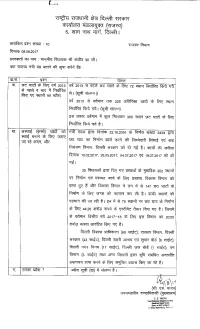

Afltt 7J^^ (71) If 713F3 T 1 ^)' Ihhath Pooja Ghat Before 2Q13

^T "HiisiJT : 10 08.08.2017 cf5t 337*. 13^R 3>. ^^^ ^t <^^ f^^J cnt 2013 ^ 2013 i< ^^ ^^ ni^t ^ f^nj 72 wr ^^rt^^^ ft^^r l^t •fT TT^^ cT ^K ^f pt^[Ra ?^ 1 ( i q^t ^ra7^ I) cf^ 2013 ^1 c^^M ^Tc^ 228 3l[riRtk1 ^^t 3> f^^ ^^^ ^^T M!R <JcfHH ^t tgcR ^^dl*< 300 ^tFT 133 W^t <^ f^P^ ^rfR^r fcF^^r ^^f ^1 71. 3WJi^ (tffEet) ^i^t <St ^T^Ft ^^cT ^T^T f^ftcf^ 22.10.2016 3^ RiuliJ ^^^T 2439 s^TCT \5TT ^t^ ch<1H, 3f^ ^^ ^T3 tUT ^RtT cprf tpf^t cf?T R5i^^l^l Rr^^ ^3 313 ^4^ul fcl'HMI, Rie^l ^TWT^ ^pT ^t ^^ ^ 1 3331 cjft ^T^STT ^TR5 10.02.2017. 25.05.2017, 04.07.2017 T^i 19.07.2017 7^t ifil 25 f(1t||ijc5i ^T7T fc^ "T^^ TR^TTcff ^^ ^dlRl^ 202 ^^F^ft ^7 f^^W 33 H^Hd ciTYTf ^ fc^^ H^diq, f^tcHTTT f^^TO ^il OT^T Jt; t 3ik ^^tPRT f^^T^ ^ ^^ if 7t 147 S3 ^13t ^1 \^\h\v\ ^> fi33 313^ c(?t Otr^TO 3ri e^^ 11 ^RtF T^TTOT ^^t OF^T0 e^^0TT7^ttl^O^t7t75 ^Ht 07 S3 ^T3 c^^ Rh^| 7f> fel^ 44.26 c67)^ 75071 c^ T^7^3 ft7fT7 f^T^ ^^ f i R^^^ 7F c|^HH Rril^ e^^ 2017-18 ^1 f^H^ ^7T ^^^FT ^il 20.00 c57i3 75O3T 3113^3 f^^ 3^ 11 ^^^ft 1^*1^ Ulltl*^3 (68 73^3), 7I3I73 15313.