Ambedkar and the Dalit Buddhist Movement in India (1950- 2000)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage ew Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISB: 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San First Printing, 2002 – 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 – 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety , for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma , is allowed after prior notification to the author. ew Cover Design Inset photo shows the famous Reclining Buddha image at Kusinara. Its unique facial expression evokes the bliss of peace ( santisukha ) of the final liberation as the Buddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the Great Stupa of Sanchi located near Bhopal, an important Buddhist shrine where relics of the Chief Disciples and the Arahants of the Third Buddhist Council were discovered. Printed in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia by: Majujaya Indah Sdn. Bhd., 68, Jalan 14E, Ampang New Village, 68000 Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Tel: 03-42916001, 42916002, Fax: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATIO This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to India from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in Buddhism, have made those journeys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

Buddhism, Democracy and Dr. Ambedkar: the Building of Indian National Identity Milind Kantilal Solanki, Pratap B

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-4, Issue-4, Jul – Aug 2019 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.4448 ISSN: 2456-7620 Buddhism, Democracy and Dr. Ambedkar: The Building of Indian National Identity Milind Kantilal Solanki, Pratap B. Ratad Assistant Professor, Department of English, KSKV Kachchh University, Bhuj, Gujrat, India Research Scholar, Department of English, KSKV Kachchh University, Bhuj, Gujrat, India Abstract— Today, people feel that democratic values are in danger and so is the nation under threat. Across nations we find different systems of government which fundamentally take care of what lies in their geographical boundaries and the human lives living within it. The question is not about what the common-man feels and how they survive, but it is about their liberty and representation. There are various forms of government such as Monarchy, Republic, Unitary State, Tribalism, Feudalism, Communism, Totalitarianism, Theocracy, Presidential, Socialism, Plutocracy, Oligarchy, Dictatorship, Meritocracy, Federal Republic, Republican Democracy, Despotism, Aristocracy and Democracy. The history of India is about ten thousand years and India is one of the oldest civilizations. The democratic system establishes the fundamental rights of human beings. Democracy also takes care of their representation and their voice. The rise of Buddhism in India paved the way for human liberty and their suppression from monarchs and monarchy. The teachings of Buddha directly and indirectly strengthen the democratic values in Indian subcontinent. The rise of Dr. Ambedkar on the socio-political stage of this nation ignited the suppressed minds and gave a new hope to them for equality and equity. -

Revista Humania Diciembre 2017 FINAL.Indd

Humania del Sur. Año 12, Nº 23. Julio-Diciembre, 2017. Santosh I. Raut Liberating India: Contextualising nationalism, democracy, and Dr. Ambedkar... pp. 65-91. Liberating India: Contextualising nationalism, democracy, and Dr. Ambedkar Santosh I. Raut EFL University, Hyderabad, India. santoshrautefl @gmail.com Abstract Dr. B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956) the principal architect of the Indian constitution, and one of the most visionary leaders of India. He is the father of Indian democracy and a nation-builder that shaped modern India. His views on religion, how it aff ects socio-political behaviour, and therefore what needs to build an egalitarian society are unique. Th erefore, this paper attempts to analyse Ambedkar’s vision of nation and democracy. What role does religion play in society and politics? Th is article also envisages to studies how caste-system is the major barrier to bring about a true nation and a harmonious society. Keywords: India, B. R. Ambedkar, national constructor, nationalism and democracy, caste system, egalitarian society. Liberación de la India: Contextualizando el nacionalismo, la democracia y el Dr. Ambedkar Resumen Dr. B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956), el principal arquitecto de la constitución india, y uno de los líderes más visionarios de la India. Él es el padre de la democracia india y el constructor de la nación que dio forma a la India moderna. Su punto de vista sobre la religión, cómo afecta el comportamiento sociopolítico y, por lo tanto, lo que necesita construir una sociedad igualitaria son únicos. Este documento intenta analizar la visión de nación y democracia de Ambedkar. ¿Qué papel juega la religión en la sociedad y en la política?. -

Ambedkar's Vision

Ambedkar’s Vision The Buddhist revival in India ignited by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar more than fifty years ago has brought millions of the country’s most impoverished and marginalized people to the Buddhist path. There is much we can learn from them, says Alan Senauke. buddhadharma: the practitioner’s quarterly SPRING 2011 62 PHOTO PHIL CLEVENGER (Facing page) Dr. B.R. Ambedkar painted on a wall in Bangalore, India With justice on our side, I do not see how we can lose our HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT, a modern Buddhist revolution is battle. The battle to me is a matter of joy… For ours is a gaining ground in the homeland of Shakyamuni. It’s being led battle not for wealth or for power. It is a battle for freedom. by Indian Buddhists from the untouchable castes, the poorest It is a battle for the reclamation of the human personality. of the poor, who go by various names: neo-Buddhists, Dalit Buddhists, Navayanists, Ambedkarites. But like so much in — Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, their lives, these names carry a subtle odor of condescension All-India Depressed Classes Conference, 1942 that suggests their kind of Buddhism is something less than the real thing. In the children’s hostels and schools of Nagpur or modest viharas in Mumbai’s Bandra East slums and the impoverished Dapodi neighborhood in Pune, one finds people singing simple PHOTOS ALAN SENAUKE H63 SPRING 2011 buddhadharma: the practitioner’s quarterly When Ambedkar returned to India to practice law, he was one of the best-educated men in the country, but, as an untouchable, he was unable to find housing and prohibited from dining with his colleagues. -

Dzogchen Forum in Moscow

No. 109 March, April 2011 Upcoming Retreats with Chögyal Namkhai Norbu Photo: G. Horner 2011 Ukraine May 14–20 Crimea retreat May 21–25 Photo: D. Ibragimov SMS Base Level exam May 26–June 6 SMS First Level Training Romania June 10–16 Merigar East Retreat Evolution Is Now Italy Dzogchen Forum in Moscow June 24–30 “The Union of Manamudra and Andrei Besedin Dzogchen” by the great Master Araga July 15–18 Thirtieth Anniversary of Merigar West n 26th–30th of April something tional Affairs, which is one of the leading in the mandala zone master-classes were unique happened in Moscow: the Moscow Universities. Rinpoche explained held. And almost half of the pavilion was August 5–12 Ofi rst Dzogchen Forum “Open tra- the meaning of Evolution, and the way in fi lled with stands of the partners, like in a Initiation and Instructions of Garuda dition – to the Open World” was held. A which all of us can enter this condition. business exposition. The central and the from Rigdzin Changchub Dorje’s Terma Forum is a format that is quite different During the next days, Rinpoche’s semi- biggest was the stand of the Dzogchen August 19–23 from a regular retreat, as it implies the nar on “Essence, Nature and Energy” was community, with bigger zones for Chögyal A special Teaching: “Dzogchen Yangti” possibility to meet and share knowledge the main event of each day. On the 29th he Namkhai Norbu and Khyentse Yeshe, and in an appropriate place, and a good chance particularly presented “Dra thal drel” – his smaller zones for North and South Kun- UK of inner development. -

Witchcraft, Religious Transformation, and Hindu Nationalism in Rural Central India

University of London The London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Anthropology Witchcraft, Religious Transformation, and Hindu Nationalism in Rural Central India Amit A. Desai Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 UMI Number: U615660 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615660 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis is an anthropological exploration of the connections between witchcraft, religious transformation, and Hindu nationalism in a village in an Adivasi (or ‘tribal’) area of eastern Maharashtra, India. It argues that the appeal of Hindu nationalism in India today cannot be understood without reference to processes of religious and social transformation that are also taking place at the local level. The thesis demonstrates how changing village composition in terms of caste, together with an increased State presence and particular view of modernity, have led to difficulties in satisfactorily curing attacks of witchcraft and magic. Consequently, many people in the village and wider area have begun to look for lasting solutions to these problems in new ways. -

AN EGALITARIAN EQUATION in INDIA TODAY (Engaged Buddhism

Volume: III, Issue: I ISSN: 2581-5828 An International Peer-Reviewed Open GAP INTERDISCIPLINARITIES - Access Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies ENGAGED DHAMMA AND TRANSFORMATION OF DALITS- AN EGALITARIAN EQUATION IN INDIA TODAY (Engaged Buddhism And The Impact Of Buddhist Philosophy In Transforming Our Social World In Terms Of Egalitarianism And Social Justice) Dr. Preeti Oza St. Andrew‟s College University of Mumbai Abstract Engaged Buddhism refers to Buddhists who are seeking ways to apply the insights from meditation practice and dharma teachings to situations of social, political, environmental, and economic suffering and injustice. The Non-duality of Personal and Social Practice is making such engagement possible even today. Buddhist teachings themselves as the restrictive social conditions within which Asian Buddhism has had to function. To survive in the often ruthless world of kings and emperors, Buddhism needed to emphasize its otherworldliness. This encouraged Buddhist institutions and Buddhist teachings (especially regarding karma and merit) to develop in ways that did not question the social order. In India today, Modern democracy and respect for human rights, however imperfectly realized, offer new opportunities for understanding the broader implications of Buddhist teachings. Furthermore, while it is true that the post/modern world is quite different from the Buddha‟s, Buddhism is thriving today because its basic principles remain just as true as when the Buddha taught them. A classic case of engaged Buddhism in India is discussed in this paper which deliberates on the Dalit- Buddhist equation in modern India. For Dalits, whose material circumstances were completely different from the higher castes, the motivation continually remained: to find out concerning suffering and to achieve its finish, in every person‟s life and in society. -

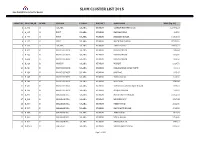

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

DECLINE and FALL of BUDDHISM (A Tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface

1 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Dr. K. Jamanadas 2 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface “In every country there are two catogories of peoples one ‘EXPLOITER’ who is winner hence rule that country and other one are ‘EXPLOITED’ or defeated oppressed commoners.If you want to know true history of any country then listen to oppressed commoners. In most of cases they just know only what exploiter wants to listen from them, but there always remains some philosophers, historians and leaders among them who know true history.They do not tell edited version of history like Exploiters because they have nothing to gain from those Editions.”…. SAMAYBUDDHA DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) By Dr. K. Jamanadas e- Publish by SAMAYBUDDHA MISHAN, Delhi DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM A tragedy in Ancient India By Dr. K. Jamanadas Published by BLUEMOON BOOKS S 201, Essel Mansion, 2286 87, Arya Samaj Road, Karol Baug, New Delhi 110 005 Rs. 400/ 3 | DECLINE AND FALL OF BUDDHISM (A tragedy in Ancient India) Author's Preface Table of Contents 00 Author's Preface 01 Introduction: Various aspects of decline of Buddhism and its ultimate fall, are discussed in details, specially the Effects rather than Causes, from the "massical" view rather than "classical" view. 02 Techniques: of brahminic control of masses to impose Brahminism over the Buddhist masses. 03 Foreign Invasions: How decline of Buddhism caused the various foreign Invasions is explained right from Alexander to Md. -

Athawale Flags Off Samanta E

PRESS RELEASE - FLAGGING OF SAMANTA EXPRESS TRAIN ON 14.2.2019 Hon’ble Minister of Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India, Shri. Ramdas Athwale has flagged off the “Samanata Express” Bharat Darshan Tourist Train at Nagpur today in the August presence of Dr. Milind Mane, MLA of East Nagpur & Hon’ble MLC Shri. Girish Vyas, and other dignitaries. Shri Somesh Kumar Divisional Railway Manager, Nagpur & Shri. Arvind Malkhede GGM/WZ/IRCTC attended the function which was held at Nagpur Railway station today morning. Indian Railways and IRCTC is jointly running the Samanata Express in memory of the Architect of our constitution and revered political leader Bharat Ratna Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. The train left Nagpur station at 11.40 hrs and will stop at Wardha, Badnera, Akola, Bhusaval, Jalgaon, Chalisgaon, Manmad, Nasik, CSMT- Mumbai for boarding of passengers. Samanata Express passengers are being taken to important places associated with Babasaheb and Gautam Buddha including Lumbini in Nepal. The train will go to Mumbai, Mhow, Gaya, Varanasi Nautanawa, Gorakhpur, and return to Nagpur. According to the programme tourists will first visit Chaityabhoomi in Mumbai following which the train will proceed to Indore and tourist will be taken to Mhow the birth place of Babasaheb by road to visit Ambedkar memorial. The train will depart to Gaya and from here proceed to Bodhgaya for overnight stay. Next day tourist will be taken to Mahabodhi temple and other tourist places including Nalanda. The train will further proceed to Varanasi to visit Saranath. On February 20, the train will arrive at Nautanwa station and tourist will be taken to Lumbini in Nepal to visit the birth place of Gautam Buddha and other Buddhist temples. -

Sacralizing the Secular. the Ethno-Fundamentalist Movements Enzo Pace1

http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-7984.2017v16n36p403 Sacralizing the Secular. The Ethno-fundamentalist movements Enzo Pace1 Abstract Religious fundamentalist movements regard the secular state as an enemy because it claims to codify its power as if God did not exist. Those movements consider their religion the repository of absolute truth, the ultimate source legitimizing human laws. Therefore, although they are post- secular, at the same time they endeavor to transform religious principles into political agendas. Indeed, militants often act in accordance with political objectives in the attempt to assert the primacy of their own faith over that of others. They move within contemporary societies in the name of a radical political theology. The main arguments based on two case studies: Bodu Bala Sena in Sri Lanka and the movements for the Hindutva in India. Keywords: Fundamentalism. Ethno-nationalism. Secular state. Introduction This article contains some reflections on the links between secularization, the secular state and fundamentalism. Religious fundamentalist movements, which act on behalf and in defense of an absolute transcendent truth, regard the secular state as an enemy because it claims to codify its power etsi Deus non daretur2, that is, independently of any religious legitimation. Those movements consider their religion the repository of absolute truth, the ultimate source legitimizing human laws. Hence the paradox of their beliefs 1 Professor de Sociologia e Sociologia da Religião na Universidade de Pádua (Itália), onde dirige o departamento de sociologia (DELETE). Professor visitante na École des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (Paris) e antigo presidente da Sociedade Internacional para a Sociologia das Religiões (ISSR/SISR). -

New Buddhism for New Aspirations

New Buddhism for New Aspirations Navayana Buddhism of Ambedkar and His Followers Virginia Hancock This article begins with an overview of Navayana Buddhism from two perspectives, that of Ambedkar himself, based on his “Buddhist gospel” The Buddha and His Dhamma, and that of practioners in Maharashtra, based available academic scholarship. In the case of Ambedkar’s understanding of Buddhism, I will focus mostly on the changes he made to more traditional presentations of Buddhism. In the case of Maharashtran practitioners, I will attempt to draw some broad conclusions about their relationship to this relatively new religion. The centrality of the figure of Ambedkar in Navayana Buddhism, as well as Navayana Buddhist’s lack of conformity with Ambedkar’s understanding of Buddhist principles as articulated in The Buddha and His Dhamma, will guide me in my conclusions about the ways outside observers might want to move forward in the study of this relatively new religion. mbedkar wrote The Buddha entirely of suffering then there is and His Dhamma with the no incentive for change. Aintent of creating a single The doctrines of no-soul, karma, text for new Buddhists to read and rebirth are incongruous. It is and follow. His introduction outlines illogical to believe that there can be four ways in which previous karma and rebirth without a soul. understandings of Buddhist doctrine The monk’s purpose has not are lacking: been presented clearly. Is he The Buddha could not have had supposed to be a “perfect man” his first great realization simply or a “social servant”? because he encountered an old As these rather sweeping man, a sick man, and a dying man.