The Trouble with Well Intended Polypharmacy in the Elderly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pharmacology of Amiodarone and Digoxin As Antiarrhythmic Agents

Part I Anaesthesia Refresher Course – 2017 University of Cape Town The Pharmacology of Amiodarone and Digoxin as Antiarrhythmic Agents Dr Adri Vorster UCT Department of Anaesthesia & Perioperative Medicine The heart contains pacemaker, conduction and contractile tissue. Cardiac arrhythmias are caused by either enhancement or depression of cardiac action potential generation by pacemaker cells, or by abnormal conduction of the action potential. The pharmacological treatment of arrhythmias aims to achieve restoration of a normal rhythm and rate. The resting membrane potential of myocytes is around -90 mV, with the inside of the membrane more negative than the outside. The main extracellular ions are Na+ and Cl−, with K+ the main intracellular ion. The cardiac action potential involves a change in voltage across the cell membrane of myocytes, caused by movement of charged ions across the membrane. This voltage change is triggered by pacemaker cells. The action potential is divided into 5 phases (figure 1). Phase 0: Rapid depolarisation Duration < 2ms Threshold potential must be reached (-70 mV) for propagation to occur Rapid positive charge achieved as a result of increased Na+ conductance through voltage-gated Na+ channels in the cell membrane Phase 1: Partial repolarisation Closure of Na+ channels K+ channels open and close, resulting in brief outflow of K+ and a more negative membrane potential Phase 2: Plateau Duration up to 150 ms Absolute refractory period – prevents further depolarisation and myocardial tetany Result of Ca++ influx -

Dabigatran Amoxicillin Clavulanate IV Treatment in the Community

BEST PRACTICE 38 SEPTEMBER 2011 Dabigatran Amoxicillin clavulanate bpac nz IV treatment in the community better medicin e Editor-in-chief We would like to acknowledge the following people for Professor Murray Tilyard their guidance and expertise in developing this edition: Professor Carl Burgess, Wellington Editor Dr Gerry Devlin, Hamilton Rebecca Harris Dr John Fink, Christchurch Dr Lisa Houghton, Dunedin Programme Development Dr Rosemary Ikram, Christchurch Mark Caswell Dr Sisira Jayathissa, Wellington Rachael Clarke Kate Laidlow, Rotorua Peter Ellison Dr Hywel Lloyd, GP Reviewer, Dunedin Julie Knight Associate Professor Stewart Mann, Wellington Noni Richards Dr Richard Medlicott, Wellington Dr AnneMarie Tangney Dr Alan Panting, Nelson Dr Sharyn Willis Dr Helen Patterson, Dunedin Dave Woods David Rankin, Wellington Report Development Dr Ralph Stewart, Auckland Justine Broadley Dr Neil Whittaker, GP Reviewer, Nelson Tim Powell Dr Howard Wilson, Akaroa Design Michael Crawford Best Practice Journal (BPJ) ISSN 1177-5645 Web BPJ, Issue 38, September 2011 Gordon Smith BPJ is published and owned by bpacnz Ltd Management and Administration Level 8, 10 George Street, Dunedin, New Zealand. Jaala Baldwin Bpacnz Ltd is an independent organisation that promotes health Kaye Baldwin care interventions which meet patients’ needs and are evidence Tony Fraser based, cost effective and suitable for the New Zealand context. Kyla Letman We develop and distribute evidence based resources which describe, facilitate and help overcome the barriers to best Clinical Advisory Group practice. Clive Cannons nz Michele Cray Bpac Ltd is currently funded through contracts with PHARMAC and DHBNZ. Margaret Gibbs nz Dr Rosemary Ikram Bpac Ltd has five shareholders: Procare Health, South Link Health, General Practice NZ, the University of Otago and Pegasus Dr Cam Kyle Health. -

Polypharmacy and the Senior Citizen: the Influence of Direct-To-Consumer Advertising

2021;69:19-25 CLINICAL GETRIATRICS - ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION doi: 10.36150/2499-6564-447 Polypharmacy and the senior citizen: the influence of direct-to-consumer advertising Linda Sperling, DHA, MSN, RN1, Martine B. Fairbanks, Ed.D, MA, BS2 1 College of nursing, University of Phoenix, Arizona, USA; 2 College of doctoral studies, University of Phoenix, Arizona, USA Background. Polypharmacy, or taking five or more medications dai- ly, can lead to poor medication compliance and an increased risk for adverse drug-to-drug interactions that may eventually lead to death. The study was designed to explore the questions of how age, the re- lationship between the physician and patient, and television, radio, magazines and modern electronic technology, such as the Internet, affect patients’ understanding of their medical care. Two main areas addressed in this research study included the pharmaceutical indus- try’s influence on consumer decisions to ask a physician for a particular medication, and the prescribing practices of the physician. Methods. This qualitative phenomenological study began with pre- screening volunteer residents in a nursing home to discover poten- tial participants who met the criteria of using five or more medicines daily. We then interviewed 24 participants who met the criteria, using semi-structured interview questions. Results. Four core themes emerged from this study: professional trust, professional knowledge, communication deficit, and direct-to-consum- Received: April 30, 2020 er advertising. Participants reported trusting their doctors and taking Accepted: November 2, 2020 medications without question, but most knew why they were taking the Correspondence medications. Participants also reported seeing ads for medications, but Linda Sperling DHA, MSN, RN only one reported asking a physician to prescribe the medication. -

Opioid Weaning Guidance Document Primary Care GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS: 1

Opioid Weaning Guidance Document Primary Care GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS: 1. Determine if the goal is a dose reduction or complete discontinuation of agent(s). 2. Weans should occur gradually to minimize the risk of withdrawal symptoms. Weaning opioids may take 6 months or more depending on the total opioid dose and the individual patient’s response to the opioid wean. There is no need to rush this process as this may only cause more distress for the patient. 3. Optimize non-opioid pain management strategies. This link provides options for non-opioid strategies: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/alternative_treatments-a.pdf a. Recommend implementing one non-opioid agent at a time b. Evaluate and discontinue any agents that are ineffective c. Do not exceed maximum recommended doses or combine multiple agents from the same medication class d. Avoid use of benzodiazepines or any sedative hypnotic agents 4. Set expectations and functional goals with patient prior to initiation of the opioid wean. 5. Educate patient on the change in opioid tolerance over time during the opioid wean and risk for overdose if they resume their starting dose or a previously stable higher dose. Discuss/prescribe naloxone to minimize the risk of overdose. 6. Screen for and treat any untreated/under-treated depression. Depression may make the weaning process more challenging. MORPHINE EQUIVALENT DOSE CALCULATOR: 1. Link to calculator: http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Calculator/DoseCalculator.htm 2. This calculator can be utilized to determine the current morphine equivalent dose your patient is receiving at baseline. If the goal is for opioid dose reduction, this calculator can also be used to determine your goal “ending” dose. -

Full Prescribing Information Warning: Suicidal Thoughts

tablets (SR) BUPROPION hydrochloride extended-release HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION anxiety, and panic, as well as suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and completed suicide. Observe hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR) was reported. However, the symptoms persisted in some Table 3. Adverse Reactions Reported by at Least 1% of Subjects on Active Treatment and at a tablets (SR) may be necessary when coadministered with ritonavir, lopinavir, or efavirenz [see Clinical These highlights do not include all the information needed to use bupropion hydrochloride patients attempting to quit smoking with Bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets, USP cases; therefore, ongoing monitoring and supportive care should be provided until symptoms resolve. Greater Frequency than Placebo in the Comparator Trial Pharmacology (12.3)] but should not exceed the maximum recommended dose. extended-release tablets (SR) safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for (SR) for the occurrence of such symptoms and instruct them to discontinue Bupropion hydrochloride Carbamazepine, Phenobarbital, Phenytoin: While not systematically studied, these drugs extended-release tablets, USP (SR) and contact a healthcare provider if they experience such adverse The neuropsychiatric safety of Bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR) was evaluated in Bupropion Bupropion may induce the metabolism of bupropion and may decrease bupropion exposure [see Clinical bupropion hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR). Nicotine events. (5.2) a randomized, double-blind, active-and placebo-controlled study that included patients without a history Hydrochloride Hydrochloride Pharmacology (12.3)]. If bupropion is used concomitantly with a CYP inducer, it may be necessary Transdermal BUPROPION hydrochloride extended-release tablets (SR), for oral use • Seizure risk: The risk is dose-related. -

Spectrum of Digoxin-Induced Ocular Toxicity: a Case Report and Literature Review Delphine Renard1*, Eve Rubli2, Nathalie Voide3, François‑Xavier Borruat3 and Laura E

Renard et al. BMC Res Notes (2015) 8:368 DOI 10.1186/s13104-015-1367-6 CASE REPORT Open Access Spectrum of digoxin-induced ocular toxicity: a case report and literature review Delphine Renard1*, Eve Rubli2, Nathalie Voide3, François‑Xavier Borruat3 and Laura E. Rothuizen1 Abstract Background: Digoxin intoxication results in predominantly digestive, cardiac and neurological symptoms. This case is outstanding in that the intoxication occurred in a nonagenarian and induced severe, extensively documented visual symptoms as well as dysphagia and proprioceptive illusions. Moreover, it went undiagnosed for a whole month despite close medical follow-up, illustrating the difficulty in recognizing drug-induced effects in a polymorbid patient. Case presentation: Digoxin 0.25 mg qd for atrial fibrillation was prescribed to a 91-year-old woman with an esti‑ mated creatinine clearance of 18 ml/min. Over the following 2–3 weeks she developed nausea, vomiting and dyspha‑ gia, snowy and blurry vision, photopsia, dyschromatopsia, aggravated pre-existing formed visual hallucinations and proprioceptive illusions. She saw her family doctor twice and visited the eye clinic once until, 1 month after starting digoxin, she was admitted to the emergency room. Intoxication was confirmed by a serum digoxin level of 5.7 ng/ml (reference range 0.8–2 ng/ml). After stopping digoxin, general symptoms resolved in a few days, but visual complaints persisted. Examination by the ophthalmologist revealed decreased visual acuity in both eyes, 4/10 in the right eye (OD) and 5/10 in the left eye (OS), decreased color vision as demonstrated by a score of 1/13 in both eyes (OU) on Ishihara pseudoisochromatic plates, OS cataract, and dry age-related macular degeneration (ARMD). -

Qato Et Al, “Changes in Prescription and Over-The-Counter Medi

Polypharmacy: time to get beyond numbers Invited commentary on: Qato et al, “Changes in prescription and over-the-counter medication and dietary supplement use among older adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011” and Jou et al, “Non-disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use to usual care providers: Findings from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey” Michael A. Steinman, MD Division of Geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco VA Health Care System Word count: 1023 References: 7 Support: Supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (K24-AG049057-01 and P30- AG044281) Acknowledgement / Disclosure: Dr. Steinman is a consultant for iodine.com, an internet start-up company. Corresponding author: Michael A. Steinman, MD 4150 Clement St, VA Box 181G San Francisco, CA 94121 [email protected] When I tell someone that I am a geriatrician, I often get the same response. I am told half- jokingly that the person needs my services. Then, I am regaled with a story of how the person’s older parent, grandparent, or spouse is prescribed an enormous number of medications, thinks they might be causing problems, and doesn’t know what to do about it. It is this view of polypharmacy that often dominates patients’, and increasingly clinicians’, experience of medication use. This skeptical perspective is largely justified. The number of medications a person uses is by far the strongest risk factor for medication-related problems. As the number of medications rises, adverse drug reactions become more common. Adherence worsens. Out-of-pocket costs rise. -

Polypharmacy in the Elderly Educational Format Faculty Expertise Required Expertise in the Field of Study

2019 AAFP FMX Needs Assessment Body System: Geriatrics Session Topic: Polypharmacy in the Elderly Educational Format Faculty Expertise Required Expertise in the field of study. Experience teaching in the field of study is desired. Preferred experience with audience Interactive REQUIRED response systems (ARS). Utilizing polling questions and Lecture engaging the learners in Q&A during the final 15 minutes of the session are required. Expertise teaching highly interactive, small group learning environments. Case-based, with experience developing and Problem- teaching case scenarios for simulation labs preferred. Other Based workshop-oriented designs may be accommodated. A typical OPTIONAL Learning PBL room is set for 50-100 participants, with 7-8 each per (PBL) round table. Please describe your interest and plan for teaching a PBL on your proposal form. Learning Objective(s) that will close Outcome Being Professional Practice Gap the gap and meet the need Measured Family physicians have 1. Use evidence-based criteria (e.g. Learners will gaps in knowledge and BEERS, STOPP, START) to submit written performance in evaluating evaluate for potentially adverse drug commitment to for potentially adverse drug events, among elderly patients change statements events, among elderly receiving multiple medications. on the session patients receiving multiple 2. Develop a systematic approach, evaluation, medications. including applicable REMS, to indicating how Family physicians have managing elderly patients with they plan to gaps in knowledge and -

Polypharmacy & Deprescribing

Lauren W. Mazzurco, DO Polypharmacy & Eastern Virginia Medical School Deprescribing [email protected] • I have no conflicts of interest to disclose Objectives • Describe the concept and impact of polypharmacy in older adults • Review the benefits of and potential barriers to deprescribing • Describe the process of rational deprescribing and demonstrate practical strategies of application to clinical scenarios https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/Downloads/2012Chartbook.pdf Scope of the problem • 30% of patients >65 are prescribed >5 medications • ~1 in 5 medications in older adults may be inappropriate • Single most predictor of harm is # of medications 1. QatoDM,AlexanderGC,ContiRM,JohnsonM, Schumm P, Lindau ST. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2867-2878. 2. RougheadEE,AndersonB,GilbertAL. Potentially inappropriate prescribing among Australian veterans and war widows/widowers. Intern Med J. 2007;37(6):402-405 3. SteinmanMA,MiaoY,BoscardinWJ,Komaiko KD, Schwartz JB. Prescribing quality in older veterans: a multifocal approach. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(10):1379-1386 4. BudnitzDS,LovegroveMC,ShehabN,Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365 (21):2002-2012. Quality Value = Cost http://ihpi.umich.edu/news/older-americans-don’t-get-–-or-seek-–-enough-help-doctors-pharmacists-drug-costs- poll-finds. Accessed -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

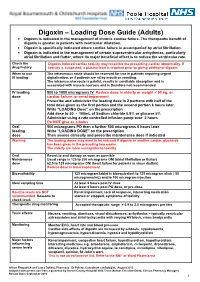

Digoxin – Loading Dose Guide (Adults) Digoxin Is Indicated in the Management of Chronic Cardiac Failure

Digoxin – Loading Dose Guide (Adults) Digoxin is indicated in the management of chronic cardiac failure. The therapeutic benefit of digoxin is greater in patients with ventricular dilatation. Digoxin is specifically indicated where cardiac failure is accompanied by atrial fibrillation. Digoxin is indicated in the management of certain supraventricular arrhythmias, particularly atrial fibrillation and flutter, where its major beneficial effect is to reduce the ventricular rate. Check the Digoxin-induced cardiac toxicity may resemble the presenting cardiac abnormality. If drug history toxicity is suspected, a plasma level is required prior to giving additional digoxin. When to use The intravenous route should be reserved for use in patients requiring urgent IV loading digitalisation, or if patients are nil by mouth or vomiting. The intramuscular route is painful, results in unreliable absorption and is associated with muscle necrosis and is therefore not recommended. IV loading 500 to 1000 micrograms IV Reduce dose in elderly or weight < 50 kg, or dose cardiac failure, or renal impairment Prescribe and administer the loading dose in 2 portions with half of the total dose given as the first portion and the second portion 6 hours later. Write “LOADING Dose” on the prescription Add dose to 50 - 100mL of Sodium chloride 0.9% or glucose 5% Administer using a rate controlled infusion pump over 2 hours Do NOT give as a bolus Oral 500 micrograms PO then a further 500 micrograms 6 hours later loading Write “LOADING DOSE” on the prescription dose Then assess clinically and prescribe maintenance dose if indicated Warning The loading doses may need to be reduced if digoxin or another cardiac glycoside has been given in the preceding two weeks. -

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH Pr WELLBUTRIN XL Bupropion

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH Pr WELLBUTRIN XL Bupropion Hydrochloride Extended-Release Tablets, USP 150 mg and 300 mg Antidepressant Name: Date of Revision: Valeant Canada LP March 20, 2017 Address: 2150 St-Elzear Blvd. West Laval, QC, H7L 4A8 Control Number: 200959 Table of Contents Page PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION .............................................................. 2 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ................................................................................. 2 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ....................................................................................... 2 CONTRAINDICATIONS ............................................................................................................ 3 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ........................................................................................... 3 ADVERSE REACTIONS ............................................................................................................. 9 DRUG INTERACTIONS ........................................................................................................... 19 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ....................................................................................... 22 OVERDOSAGE ......................................................................................................................... 24 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ..................................................................... 25 STORAGE AND STABILITY ..................................................................................................