The Essential Role of Charge-Shift Bonding in Hypervalent Prototype Xef2 Benoît Braïda, Philippe C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Courses of Study for Generic Elective 'B

COURSES OF STUDY FOR GENERIC ELECTIVE 'B. Sc, HODs' PROGRAMME IN "CHEMISTRY" GENERIC ELECTIVE All Four Generic Papers (One paper to be studied in each semester) of Chemistry to be studied by the Students of Other than Chemistry Honours. SEM- I Generic Elective Papers (GE-l) (Minor-Chemistry) (any four) for other Departments/ Disciplines: (Credit: 06 each) GE: ATOMIC STRUCTURE, BONDING, GENERAL ORGANIC CHEMISTRY & ALIPHATIC HYDROCARBONS (Credits: Theory-04, Practicals-02) Theory: 60 Lectures Section A: Inorganic Chemistry-I (30 Periods) Atomic Structure: Review of Bohr's theory and its limitations, dual behaviour of matter and radiation, de Broglie's relation, Heisenberg Uncertainty principle. Hydrogen atom spectra. Need of a new approach to Atomic structure. What is Quantum mechanics? Time independent Schrodinger equation and meaning of various terms in it. Significance of !fl and !fl2, Schrodinger equation for hydrogen atom. Radial and angular parts of the hydogenic wavefunctions (atomic orbitals) and their variations for Is, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p and 3d orbitals (Only graphical representation). Radial and angular nodes and their significance. Radial distribution functions and the concept of the most probable distance with special reference to Is and 2s atomic orbitals. Significance of quantum numbers, orbital angular momentum and quantum numbers m I and m«. Shapes of s, p and d atomic orbitals, nodal planes. Discovery of spin, spin quantum number (s) and magnetic spin quantum number (ms). Rules for filling electrons in various orbitals, Electronic configurations of the atoms. Stability of half-filled and completely filled orbitals, concept of exchange energy. Relative energies of atomic orbitals, Anomalous electronic configurations. -

Topological Analysis of the Metal-Metal Bond: a Tutorial Review Christine Lepetit, Pierre Fau, Katia Fajerwerg, Myrtil L

Topological analysis of the metal-metal bond: A tutorial review Christine Lepetit, Pierre Fau, Katia Fajerwerg, Myrtil L. Kahn, Bernard Silvi To cite this version: Christine Lepetit, Pierre Fau, Katia Fajerwerg, Myrtil L. Kahn, Bernard Silvi. Topological analysis of the metal-metal bond: A tutorial review. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, Elsevier, 2017, 345, pp.150-181. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.04.009. hal-01540328 HAL Id: hal-01540328 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01540328 Submitted on 16 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Topological analysis of the metal-metal bond: a tutorial review Christine Lepetita,b, Pierre Faua,b, Katia Fajerwerga,b, MyrtilL. Kahn a,b, Bernard Silvic,∗ aCNRS, LCC (Laboratoire de Chimie de Coordination), 205, route de Narbonne, BP 44099, F-31077 Toulouse Cedex 4, France. bUniversité de Toulouse, UPS, INPT, F-31077 Toulouse Cedex 4, i France cSorbonne Universités, UPMC, Univ Paris 06, UMR 7616, Laboratoire de Chimie Théorique, case courrier 137, 4 place Jussieu, F-75005 Paris, France Abstract This contribution explains how the topological methods of analysis of the electron density and related functions such as the electron localization function (ELF) and the electron localizability indicator (ELI-D) enable the theoretical characterization of various metal-metal (M-M) bonds (multiple M-M bonds, dative M-M bonds). -

Chapter 4, Lesson 5: Energy Levels, Electrons, and Ionic Bonding

Chapter 4, Lesson 5: Energy Levels, Electrons, and Ionic Bonding Key Concepts • The attractions between the protons and electrons of atoms can cause an electron to move completely from one atom to the other. • When an atom loses or gains an electron, it is called an ion. • The atom that loses an electron becomes a positive ion. • The atom that gains an electron becomes a negative ion. • A positive and negative ion attract each other and form an ionic bond. Summary Students will look at animations and make drawings of the ionic bonding of sodium chloride (NaCl). Students will see that both ionic and covalent bonding start with the attractions of pro- tons and electrons between different atoms. But in ionic bonding, electrons are transferred from one atom to the other and not shared like in covalent bonding. Students will use Styrofoam balls to make models of the ionic bonding in sodium chloride (salt). Objective Students will be able to explain the process of the formation of ions and ionic bonds. Evaluation The activity sheet will serve as the “Evaluate” component of each 5-E lesson plan. The activity sheets are formative assessments of student progress and understanding. A more formal summa- tive assessment is included at the end of each chapter. Safety Be sure you and the students wear properly fitting goggles. Materials for Each Group • Black paper • Salt • Cup with salt from evaporated saltwater • Magnifier • Permanent marker Materials for Each Student • 2 small Styrofoam balls • 2 large Styrofoam balls • 2 toothpicks ©2016 American Chemical Society Middle School Chemistry - www.middleschoolchemistry.com 337 Note: In an ionically bonded substance such as NaCl, the smallest ratio of positive and negative ions bonded together is called a “formula unit” rather than a “molecule.” Technically speaking, the term “molecule” refers to two or more atoms that are bonded together covalently, not ioni- cally. -

Chemical Forces Understanding the Relative Melting/Boiling Points of Two

Chapter 8 – Chemical Forces Understanding the relative melting/boiling points of two substances requires an understanding of the forces acting between molecules of those substances. These intermolecular forces are important for many additional reasons. For example, solubility and vapor pressure are governed by intermolecular forces. The same factors that give rise to intermolecular forces (e.g. bond polarity) can also have a profound impact on chemical reactivity. Chemical Forces Internuclear Distances and Atomic Radii There are four general methods of discussing interatomic distances: van der Waal’s, ionic, covalent, and metallic radii. We will discuss the first three in this section. Each has a unique perspective of the nature of the interaction between interacting atoms/ions. Van der Waal's Radii - half the distance between two nuclei of the same element in the solid state not chemically bonded together (e.g. solid noble gases). In general, the distance of separation between adjacent atoms (not bound together) in the solid state should be the sum of their van der Waal’s radii. F F van der Waal's radii F F Ionic Radii – Ionic radii were discussed in Chapter 4 and you should go back and review that now. One further thing is worth mentioning here. Evidence that bonding really exists and is attractive can be seen in ionic radii. For all simple ionic compounds, the ions attain noble gas configurations (e.g. in NaCl the Na+ ion is isoelectronic to neon and the Cl- ion is isoelectronic to argon). For the sodium chloride example just given, van der Waal’s radii would predict (Table 8.1, p. -

Starter for Ten 3

Learn Chemistry Starter for Ten 3. Bonding Developed by Dr Kristy Turner, RSC School Teacher Fellow 2011-2012 at the University of Manchester, and Dr Catherine Smith, RSC School Teacher Fellow 2011-2012 at the University of Leicester This resource was produced as part of the National HE STEM Programme www.rsc.org/learn-chemistry Registered Charity Number 207890 3. BONDING 3.1. The nature of chemical bonds 3.1.1. Covalent dot and cross 3.1.2. Ionic dot and cross 3.1.3. Which type of chemical bond 3.1.4. Bonding summary 3.2. Covalent bonding 3.2.1. Co-ordinate bonding 3.2.2. Electronegativity and polarity 3.2.3. Intermolecular forces 3.2.4. Shapes of molecules 3.3. Properties and bonding Bonding answers 3.1.1. Covalent dot and cross Draw dot and cross diagrams to illustrate the bonding in the following covalent compounds. If you wish you need only draw the outer shell electrons; (2 marks for each correct diagram) 1. Water, H2O 2. Carbon dioxide, CO2 3. Ethyne, C2H2 4. Phosphoryl chloride, POCl3 5. Sulfuric acid, H2SO4 Bonding 3.1.1. 3.1.2. Ionic dot and cross Draw dot and cross diagrams to illustrate the bonding in the following ionic compounds. (2 marks for each correct diagram) 1. Lithium fluoride, LiF 2. Magnesium chloride, MgCl2 3. Magnesium oxide, MgO 4. Lithium hydroxide, LiOH 5. Sodium cyanide, NaCN Bonding 3.1.2. 3.1.3. Which type of chemical bond There are three types of strong chemical bonds; ionic, covalent and metallic. -

Identification of a Simplest Hypervalent Hydrogen Fluoride

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Identification of a Simplest Hypervalent Hydrogen Fluoride Anion in Solid Argon Received: 19 December 2016 Meng-Chen Liu1, Hui-Fen Chen2, Chih-Hao Chin1, Tzu-Ping Huang1, Yu-Jung Chen3 & Yu-Jong Accepted: 18 April 2017 Wu1,4 Published: xx xx xxxx Hypervalent molecules are one of the exceptions to the octet rule. Bonding in most hypervalent molecules is well rationalized by the Rundle–Pimentel model (three-center four-electron bond), and high ionic bonding between the ligands and the central atom is essential for stabilizing hypervalent molecules. Here, we produced one of the simplest hypervalent anions, HF−, which is known to deviate from the Rundle–Pimentel model, and identified its ro-vibrational features. High-levelab inito calculations reveal that its bond dissociation energy is comparable to that of dihalides, as supported by secondary photolysis experiments with irradiation at various wavelengths. The charge distribution analysis suggested that the F atom of HF− is negative and hypervalent and the bonding is more covalent than ionic. The octet rule indicates that atoms of the main group elements tend to gain or lose electrons in order to have eight electrons in their valence shells1, 2, similar to the electronic configuration of the noble gases. Therefore, to attain this fully filled electronic configuration, atoms combine to form molecules by sharing their valence electrons to form chemical bonds. This rule is especially applicable to the period 2 and 3 elements. Most molecules are formed by following this rule and the bonding structure of molecules can be easily recognized by using Lewis electron dot diagrams. -

The Different Types of Bonds Atoms Form Bonds with Other Atoms in Order to Have a Full Outer Shell of Electrons Like the Noble Gases

Reading- The Different Types of Bonds Atoms form bonds with other atoms in order to have a full outer shell of electrons like the noble gases. If an atom has too few or too many valence electrons it will have to gain, lose, or share those outer electrons with another atom in order to become “happy” or in chemistry terms, more stable. There are many types of chemical bonds that can form, however the 3 main types are: ionic, covalent, and metallic bonds. You must become familiar with how they work and the differences between the 3 types. I. Ionic bonding: Model 1 is a description of what chemists call ionic bonding. Ionic bonding occurs strictly between metal and nonmetal atoms. In ionic bonding some of the valence electrons of a metal atom are transferred to a nonmetal atom so that each atom ends up with a noble gas configuration. Usually one, two, or three electrons are transferred from one atom to another. This transfer of an electron causes the metal atom to have a net positive charge (+) and the nonmetal atom to have a net negative charge (-). The individual atoms in ionic solids are referred to as ions because of their charges. These opposite charges are attracted to one another. On the right is a drawing of a chunk of salt, NaCl, a very common ionic substance. Notice how the sodium and chloride ions alternate throughout the structure. The positive and negative ions alternating in three dimensions make the solid quite strong because of their strong attractions to one another. -

13 Intermolecular Forces, Liquids, and Solids

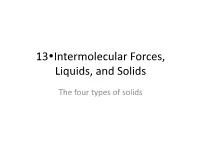

13Intermolecular Forces, Liquids, and Solids The four types of solids Intermolecular Forces of Attraction • Ch 12 was all about gases… particles that don’t attract each other. Intermolecular Forces of Attraction • Ch 13 is about liquids and solids… where the attraction between particles allows the formation of solids and liquids. Intermolecular Forces of Attraction • These attractions are called “intermolcular forces of attractions” or IMF’s for short. • Intermolcular forces vs intramolecular forces Four Solids – Overview • Molecular Solids (particles with IMF’s) • Metals (metallic bonding) • Ionic Solids (ionic bonding) • Covalent Network Solids (covalent bonding) Molecular Solids • Molecules or noble gases (individual particles) Molecular Solid Examples • H O 2 • C2H5OH • CO2 • C6H12O6 • CH 4 • The alkanes, alkenes, etc. • NH 3 • The diatomic molecules • NO 2 • The noble gases • CO • C2H6 Metals • A lattice of positive ions in a “sea of electrons” • Metal atoms have low electronegativity Metal Examples • Pb • Brass (Cu + Zn) • Ag • Bronze (Cu + Sn) • Au • Stainless Steel (Fe/Cr/C) • Cu • Zn • Fe Ionic Solids • A lattice of positive and negative ions Ionic Solid Examples • NaCl • CaCl2 • KCl • MgSO4 • KI • Fe2O3 • FeCl3 • AgNO3 • CaCO3 • + ion & - ion Covalent Network Solids • Crystal held together with covalent bonds Covalent Network Solid Examples • C(diamond) • C(graphite) • SiO2 (quartz, sand, glass) • SiC • Si • WC • BN Properties of Metals Metals are good conductors of heat and electricity. They are shiny and lustrous. Metals can be pounded into thin sheets (malleable) and drawn into wires (ductile). Metals do not hold onto their valence electrons very well. They have low electronegativity. Properties of Ionic Solids • Brittle • High MP & BP • Dissolves in H2O • Conducts as (l), (aq), (g) Electrical Conductivity Intermolecular Forces (IMFs) • Each intermolecular force involves + and – attractions. -

Pushing 3C–4E Bonds to the Limit: a Coupled Cluster Study of Stepwise

Article Cite This: Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 14777−14789 pubs.acs.org/IC Pushing 3c−4e Bonds to the Limit: A Coupled Cluster Study of Stepwise Fluorination of First-Row Atoms Vytor P. Oliveira,† Elfi Kraka,‡ and Francisco B. C. Machado*,† † Instituto Tecnologicó de Aeronauticá (ITA), Departamento de Química, Saõ Josédos Campos, 12228-900 Saõ Paulo, Brazil ‡ Department of Chemistry, Southern Methodist University, 3215 Daniel Avenue, Dallas, Texas 75275-0314, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: To better understand why hypervalent F, O, N, C, and B compounds are rarely stable, we carried out a systematic study of 28 systems, including anionic, cationic, and neutral molecules, held together by covalent, hypervalent, and noncovalent bonds. Molecular geometries, frequencies, atomic charges, electrostatic potentials, energy and electron densities, Mayer bond orders, local stretching force constants, and bond strength orders (BSOs) were derived from high accuracy CCSD(T) calculations and utilized to compare the strength and nature of hypervalent bonds with other types of bonds. All hypervalent molecules studied in this work were found to be either first-order transition states or unstable to dissociation, − − with F3 and OF3 as the only exceptions. For several systems, we found that a weak noncovalent bonded complex is more stable than a hypervalent one, due to the high energetic cost to accommodate an extra ligand, which can surpass the stability gained by 3c−4e bonding. 29−31 ■ INTRODUCTION (SN2). A better understanding of the bonding mechanism There are significant differences between the chemistry of first in these TS structures could help to improve the selectivity 1,2 and/or to reduce the activation energy of these reactions. -

Bio 12 Chapter 2 Test Review 1.Know the Difference Between Ionic And

Bio 12 Chapter 2 Test Review 1.Know the difference between ionic and covalent bonds In order to complete outer shells in electrons bonds can be Ionic; one atom donates or receives electrons Covalent; atoms share electrons 2. Know what a polar covalent bond is: bond that has UNEQUAL sharing of electrons 3. Be able to explain why water is a polar molecule *Polar bonds have charges on either end and often attract to each other *Atoms ‘hogging’ the electrons have an electronegative charge, and atoms ‘lacking’ electrons have an electropositive charge 4. Explain what a hydrogen bond is and why it is important Electronegative atoms on one molecule are attracted to electropositive atoms on a different molecule. Form Hydrogen bonds. 5. Explain the unique characteristics of water and explain how they are useful to organisms (poster you made) *Water molecules are attracted to other polar molecules cohesion – when one water molecule is attracted to another water molecule adhesion – when polar molecules other than water stick to a water molecule (Steady column of water) *Water warms up and cools down slowly (high heat capacity) *Water has a high heat of vaporization because so many hydrogen bonds must be broken for water to evaporate *A solution consists of a solute dissolved into a solvent *Water’s hydrogen bonds help it dissolve other polar molecules *Frozen Water is Less Dense than Liquid Water and floats on liquid water 6. Explain the difference between an acid and a base and what pH is. pH is the Measurement of Acidity (acid) or Alkalinity (base) of a Solution. -

Chemical Bonding

CHEMICAL BONDING 1 18 1A 8A 1 2 13 14 15 16 17 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A 2 1+ 2+ 3- 2- 1- 3 1+ 2+ 2- 1- 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 1+ 2+ 3+ 4+ 5+ 3+ 2+ 3+ 2+ 2+ 2+ 2+ 3+ 2- 1- 5 1+ 2+ 3+ 4+ 5+ 2- 1- 6 1+ 2+ 3+ 7 2+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ 3+ Neutral Atom Positive Ion by Negative Ion DR. STEPHEN THOMPSON MR. JOE STALEY The contents of this module were developed under grant award # P116B-001338 from the Fund for the Improve- ment of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), United States Department of Education. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of FIPSE and the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal government. CHEMICAL BONDING CONTENTS 2 Electronegativity 3 Road Map 4 Types Of Bonding 5 Properties Controlled By Chemical Bond 6 Polar Bonds 7 Metallic Bonding 8 Intermolecular Forces 9 Ions: Counting Electrons And Protons 10 Ionic And Atomic Radii 11 Ions And Energy 12 Lithium Fluoride 13 Crystal Packing 14 Crystal Packing 15 Crystal Packing 16 Covalent H2 17 Quantization 18 Bond Length And Strength 19 Strong And Weak Bonds 20 Strong And Weak Bonds 21 Covalent To Metallic 22 Electron Delocalization CHEMICAL BONDING ELECTRONEGATIVITY Hydrogen 1 Metals 18 Electronegativity 1A Metalloids 8A 2.1 2 Nonmetals 13 14 15 16 17 0 H 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A He Group 18 0.98 1.57 2.04 2.55 3.04 3.44 3.98 0 Li Be B C N O F Ne 0.93 1.31 1.61 1.9 2.19 2.58 3.16 0 Na Mg 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Al Si P S Cl Ar 0.82 1 1.36 1.54 1.63 1.66 1.55 1.83 1.88 1.91 -

Intramolecular & Intermolecular Forces

TutorTube: Intramolecular & Intermolecular Forces Spring 2020 Introduction Hello and welcome to TutorTube, where The Learning Center’s Lead Tutors help you understand challenging course concepts with easy to understand videos. My name is Manal, Lead Tutor for sciences. In today’s video, we will explore different intramolecular and intermolecular forces. We will define, visualize, and compare all of these forces: covalent, ionic, metallic, London dispersion, dipole- dipole, hydrogen bonding, and ion-dipole. Let’s get started! Definitions To start, let’s define intramolecular and intermolecular. ‘Intra’ means within, so intramolecular forces occur within a molecule. ‘Inter’ means between, so intermolecular forces occur between molecules. The difference can be seen in this image. Image 1 (“Intramolecular and Intermolecular Forces”) Covalent Bonds The three types of intramolecular forces are covalent, ionic, and metallic bonding. Covalent bonds occur between two nonmetals. In this type of bond, the atoms share electrons. There are two types of covalent bonds: polar and nonpolar. Polar covalent bonds are between two atoms that have a difference in electronegativity. This difference in electronegativity causes unequal sharing of electrons, resulting in the more electronegative atom to have a partial negative charge, and the other atom to have a partial positive charge. In this image, the intramolecular attraction is a polar bond. Contact Us – Sage Hall 170 – (940) 369-7006 [email protected] - @UNTLearningCenter 2 Image 2 (“Intramolecular and Intermolecular Forces”) Nonpolar covalent bonds are between two atoms that have equal electronegativity, which is typically two of the same atoms, or between a carbon and a hydrogen. Electrons are shared equally, so no partial charges occur.