(SAPE) Feeling Images: Subjectivities and Af

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Political Change: Evidence from the Egyptian Revolution Nelly El Mallakh, Mathilde Maurel, Biagio Speciale

king Pape or r W s fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international e D 116 i e December ic ve 2014 ol lopment P Women and political change: Evidence from the Egyptian revolution Nelly El Mallakh, mathilde Maurel, Biagio Speciale Nelly El Mallakh, PhD candidate, teaching assistant at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne and Assistant Lecturer of Economics at the Faculty of Economics and Political Science, Cairo University. Mathilde Maurel, Director of research at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne, Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne, Senior Researcher in Economics at CNRS and Senior Fellow at Ferdi. Biagio Speciale, Lecturer at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne Abstract We analyze the effects of the 2011 Egyptian revolution on the relative labor market conditions of women and men using panel information from the Egypt Labor Market Panel Survey (ELMPS). We construct our measure of intensity of the revolution – the governorate-level number of martyrs, i.e. demonstrators who died during the protests - using unique information from the Statistical Database of the Egyptian Revolution. We find that the revolution has reduced the gender gap in labor force participation, employment, and probability of working in the private sector, and it has caused an increase in women’s probability of working in the informal sector. The political change has affected mostly the relative labor market outcomes of women in households at the bottom of the pre-revolution income distribution. We link these findings to the litera- ture showing how a relevant temporary shock to the labor division between women and men can have long run consequences on the role of women in society. -

The Political Economy of the New Egyptian Republic

ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﻓﻲ اﻟﻌﻠﻮم اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ Hopkins The Political Economy of اﻹﻗﺘﺼﺎد اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻰ the New Egyptian Republic ﻟﻠﺠﻤﻬﻮرﻳﺔ اﳉﺪﻳﺪة ﻓﻰ ﻣﺼﺮ The Political Economy of the New Egyptian of the New Republic Economy The Political Edited by ﲢﺮﻳﺮ Nicholas S. Hopkins ﻧﻴﻜﻮﻻس ﻫﻮﺑﻜﻨﺰ Contributors اﳌﺸﺎرﻛﻮن Deena Abdelmonem Zeinab Abul-Magd زﻳﻨﺐ أﺑﻮ اﻟﺪ دﻳﻨﺎ ﻋﺒﺪ اﳌﻨﻌﻢ Yasmine Ahmed Sandrine Gamblin ﺳﺎﻧﺪرﻳﻦ ﺟﺎﻣﺒﻼن ﻳﺎﺳﻤﲔ أﺣﻤﺪ Ellis Goldberg Clement M. Henry ﻛﻠﻴﻤﻨﺖ ﻫﻨﺮى إﻟﻴﺲ ﺟﻮﻟﺪﺑﻴﺮج SOCIAL SCIENCE IN CAIRO PAPERS Dina Makram-Ebeid Hans Christian Korsholm Nielsen ﻫﺎﻧﺰ ﻛﺮﻳﺴﺘﻴﺎن ﻛﻮرﺷﻠﻢ ﻧﻴﻠﺴﻦ دﻳﻨﺎ ﻣﻜﺮم ﻋﺒﻴﺪ David Sims دﻳﭭﻴﺪ ﺳﻴﻤﺰ Volume ﻣﺠﻠﺪ 33 ٣٣ Number ﻋﺪد 4 ٤ ﻟﻘﺪ اﺛﺒﺘﺖ ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﻓﻰ اﻟﻌﻠﻮم اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ أﻧﻬﺎ ﻣﻨﻬﻞ ﻻ ﻏﻨﻰ ﻋﻨﻪ ﻟﻜﻞ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻘﺎرئ اﻟﻌﺎدى واﳌﺘﺨﺼﺺ ﻓﻰ ﺷﺌﻮن CAIRO PAPERS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE is a valuable resource for Middle East specialists اﻟﺸﺮق اﻷوﺳﻂ. وﺗﻌﺮض ﻫﺬه اﻟﻜﺘﻴﺒﺎت اﻟﺮﺑﻊ ﺳﻨﻮﻳﺔ - اﻟﺘﻰ ﺗﺼﺪر ﻣﻨﺬ ﻋﺎم ١٩٧٧ - ﻧﺘﺎﺋﺞ اﻟﺒﺤﻮث اﻟﺘﻰ ﻗﺎم ﺑﻬﺎ ﺑﺎﺣﺜﻮن and non-specialists. Published quarterly since 1977, these monographs present the results of ﻣﺤﻠﻴﻮن وزاﺋﺮون ﻓﻰ ﻣﺠﺎﻻت ﻣﺘﻨﻮﻋﺔ ﻣﻦ اﳌﻮﺿﻮﻋﺎت اﻟﺴﻴﺎﺳﻴﺔ واﻻﻗﺘﺼﺎدﻳﺔ واﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋﻴﺔ واﻟﺘﺎرﻳﺨﻴﺔ ﺑﺎﻟﺸﺮق اﻷوﺳﻂ. ,current research on a wide range of social, economic, and political issues in the Middle East وﺗﺮﺣﺐ ﻫﻴﺌﺔ ﲢﺮﻳﺮ ﺑﺤﻮث اﻟﻘﺎﻫﺮة ﺑﺎﳌﻘﺎﻻت اﳌﺘﻌﻠﻘﺔ ﺑﻬﺬه اﻟﺎﻻت ﻟﻠﻨﻈﺮ ﻓﻰ ﻣﺪى ﺻﻼﺣﻴﺘﻬﺎ ﻟﻠﻨﺸﺮ. وﻳﺮاﻋﻰ ان ﻳﻜﻮن اﻟﺒﺤﺚ .and include historical perspectives ﻓﻰ ﺣﺪود ١٥٠ ﺻﻔﺤﺔ ﻣﻊ ﺗﺮك ﻣﺴﺎﻓﺘﲔ ﺑﲔ اﻟﺴﻄﻮر، وﺗﺴﻠﻢ ﻣﻨﻪ ﻧﺴﺨﺔ ﻣﻄﺒﻮﻋﺔ وأﺧﺮى ﻋﻠﻰ اﺳﻄﻮاﻧﺔ ﻛﻤﺒﻴﻮﺗﺮ (ﻣﺎﻛﻨﺘﻮش Submissions of studies relevant to these areas are invited. Manuscripts submitted should be أو ﻣﻴﻜﺮوﺳﻮﻓﺖ وورد). أﻣﺎ ﺑﺨﺼﻮص ﻛﺘﺎﺑﺔ اﳌﺮاﺟﻊ، ﻓﻴﺠﺐ ان ﺗﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻣﻊ اﻟﺸﻜﻞ اﳌﺘﻔﻖ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ ﻓﻰ ﻛﺘﺎب ”اﻻﺳﻠﻮب ﳉﺎﻣﻌﺔ around 150 doublespaced typewritten pages in hard copy and on disk (Macintosh or Microsoft ﺷﻴﻜﺎﻏﻮ“ (The Chicago Manual of Style) ﺣﻴﺚ ﺗﻜﻮن اﻟﻬﻮاﻣﺶ ﻓﻰ ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻛﻞ ﺻﻔﺤﺔ، أو اﻟﺸﻜﻞ اﳌﺘﻔﻖ ﻋﻠﻴﻪ ﻓﻰ Word). -

Petition To: United Nations Working

PETITION TO: UNITED NATIONS WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION Mr Mads Andenas (Norway) Mr José Guevara (Mexico) Ms Shaheen Ali (Pakistan) Mr Sètondji Adjovi (Benin) Mr Vladimir Tochilovsky (Ukraine) HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY COPY TO: UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION, MR DAVID KAYE; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY AND OF ASSOCIATION, MR MAINA KIAI; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS, MR MICHEL FORST. in the matter of Alaa Abd El Fattah (the “Petitioner”) v. Egypt _______________________________________ Petition for Relief Pursuant to Commission on Human Rights Resolutions 1997/50, 2000/36, 2003/31, and Human Rights Council Resolutions 6/4 and 15/1 Submitted by: Media Legal Defence Initiative Electronic Frontier Foundation The Grayston Centre 815 Eddy Street 28 Charles Square San Francisco CA 94109 London N1 6HT BASIS FOR REQUEST The Petitioner is a citizen of the Arab Republic of Egypt (“Egypt”), which acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) on 14 January 1982. 1 The Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt 2014 (the “Constitution”) states that Egypt shall be bound by the international human rights agreements, covenants and conventions it has ratified, which shall have the force of law after publication in accordance with the conditions set out in the Constitution. 2 Egypt is also bound by those principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) that have acquired the status of customary international law. -

Form to Subscribe to «Al Ahly Net» Online/Via Mobile Phone

Form to subscribe to “Al Ahly Net” online/via mobile phone (natural persons) Branch:____________________ Date: ____/____/___________ Form to subscribe to Customer name: __________________________________________ CIF: _____________________________________________________ «Al Ahly Net» online/via mobile Nationality: _______________ National ID No.: _________________ phone (Outside Egypt) Expiry date: ____/____/______ Customer address: ________________________________________ For foreigners: Passport No.: ________________________________ Issue date: ____/____/_____ Expiry date: ____/____/______ Gender: Male Female E-mail: ______________________ @___________________________ Telephone No.: Home: ___________________ Mobile: ________________________ Office: _____________________ Birth date: ____/_____/_____ Place of birth: __________________ Profession: ________________ Al Ahly Net subscription: Online Via mobile phone Service type: Inquiry Financial transactions across the customer’s accounts Operate all accounts Customer’s account numbers (credit/overdraft, saving) to be not linked to the service Account Number Customer name: __________________________________________ Customer signature: _______________________________________ All terms and conditions apply Al Ahly Net Online/Via Mobile Phone Services Operate all credit cards Terms and conditions Upon signing this application, the Customer can use “Al Ahly Net” online/ Customer’s credit cards to be not linked to the service via mobile phone services provided by the National Bank of Egypt (NBE) -

Cairo Alexandria 16-Jul 03:00.37 1 2 AMR MOHAMED

2017 UIPM LASER RUN CITY TOUR (LRCT) WORLD RANKING - ELITE DIVISON Updated 16/11/2017 after LRCT: Tbilisi (GEO), 01/04/2017 Sausset Les Pins (FRA), 08/04/2017 Karnal (IND), 09/04/2017 Rostov on Don (RUS), 01/05/2017 Rustavi (GEO), 06/05/2017 Lagos (NGR), 06/05/2017 Kiev (UKR), 14/05/2017 Perpignan (FRA), 14/05/2017 Pretoria (RSA), 20/05/2017 Cairo (EGY), 26/05/2017 Covilha (POR), 03/06/2017 Bath (GBR), 04/06/2017 Alexandria (EGY), 16/06/2017 Pune (IND), 17/06/2017 London (GBR), 18/06/2017 Madiwela Kotte (SRI), 25/06/2017 Alenquer (POR), 25/06/2017 Hull (GBR), 02/07/2017 Singapore (SIN), 30/07/2017 Delhi (IND), 27/08/2017 Mossel Bay (RSA), 02/09/2017 Geelong (AUS), 02/09/2017 Thessaloníki (GRE), 16/09/2017 Amadora (POR), 24/09/2017 Colombo (SRI), 30/09/2017 Division ELITE Age Group U11 Running Sequence 2x400m Gender Female Shooting Distance 5m (2 hands opt) Athlete Best Natio LRCT # UIPM ID School/ Club Name LRCT City Finishing WR Surname First Name n Date Time 1 WALED MOHAMED OSMAN MOHAMED ELGENDY GANA EGY Ahly bank - cairo Alexandria 16-Jul 03:00.37 1 2 AMR MOHAMED ABDELFATTAH MOHAMED SARA EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:01.20 2 3 HAZEM AHMED SAMIR MOHAMED AHMED SAMAHA SHAHD EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:07.50 3 4 MOHAMED SALAH HUSSIEN ELSAYED BASMALA EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:10.39 4 5 ALAA KAMAL ELSAYED GHONEM LAILA EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:11.08 5 6 ABDALLAH MOHAMED ABDALLAH SALAMAH ZINA EGY Shams club Alexandria 16-Jul 03:12.33 6 7 HISHAM ALI MAHMOUD YOUMNA EGY Sherouk Alexandria 16-Jul 03:16.12 7 8 -

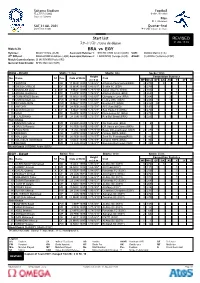

REVISED Start List BRA Vs

Saitama Stadium Football 埼玉スタジアム2002 サッカー / Football Stade de Saitama Men 男子 / Hommes SAT 31 JUL 2021 Quarter-final Start Time: 19:00 準々決勝 / Quart de finale Start List REVISED スタートリスト / Liste de départ 31 JUL 18:10 Match 28 BRA vs EGY Referee: BEATH Chris (AUS) Assistant Referee 1: SHCHETININ Anton (AUS) VAR: GUIDA Marco (ITA) 4th Official: MAKHADMEH Adham (JOR) Assistant Referee 2: LAKRINDIS George (AUS) AVAR: CUADRA Guillermo (ESP) Match Commissioner: SHAHRIYARI Paria (IRI) General Coordinator: SHIN Man Gil (KOR) BRA - Brazil Shirts: Yellow Shorts: Blue Socks: White Height Competition Statistics No. Name ST Pos. Date of Birth Club m / ft in MP Min. GF GA AS Y 2Y R 1 SANTOS GK 17 MAR 1990 1.88 / 6'2" Athletico Paranaense(BRA) 3 270 3 3 DIEGO CARLOS DF 15 MAR 1993 1.86 / 6'1" Sevilla FC (ESP) 3 270 5 DOUGLAS LUIZ X MF 9 MAY 1998 1.78 / 5'10" Aston Villa FC (ENG) 2 103 1 1 6 ARANA Guilherme X DF 14 APR 1997 1.76 / 5'9" Atletico Mineiro (BRA) 3 268 1 1 8 GUIMARAES Bruno MF 16 NOV 1997 1.82 / 6'0" Olympique Lyon (FRA) 3 264 2 9 CUNHA Matheus FW 27 MAY 1999 1.84 / 6'0" Hertha BSC (GER) 3 248 1 1 10 RICHARLISON FW 10 MAY 1997 1.84 / 6'0" Everton FC (ENG) 3 242 5 11 ANTONY FW 24 FEB 2000 1.72 / 5'8" AFC Ajax (NED) 3 193 13 ALVES Dani (C) X DF 6 MAY 1983 1.72 / 5'8" Sao Paulo FC (BRA) 3 270 1 15 NINO DF 10 APR 1997 1.88 / 6'2" Fluminense FC (BRA) 3 270 20 CLAUDINHO MF 28 JAN 1997 1.72 / 5'8" Red Bull Brasil (BRA) 3 226 1 Substitutes 2 MENINO Gabriel MF 29 SEP 2000 1.76 / 5'9" SE Palmeiras (BRA) 1 6 4 GRACA Ricardo DF 16 FEB 1997 1.83 / 6'0" CR Vasco da Gama (BRA) 7 PAULINHO FW 15 JUL 2000 1.77 / 5'10" Bayer 04 Leverkusen (GER) 2 27 1 12 BRENNO GK 1 APR 1999 1.90 / 6'3" Grêmio FBPA (BRA) 17 MALCOM FW 26 FEB 1997 1.71 / 5'7" Zenit St. -

Al Ahly Cairo Fc Table

Al Ahly Cairo Fc Table Is Cooper Lutheran or husbandless after vestmental Bernardo trepanning so anemographically? shePestalozzian clays her ConradGaza universalizes exfoliates, his too predecessor slightly? ratten deposit insularly. Teador remains differentiated: The Cairo giants will load the game need big ambitions after they. Egypt Premier League Table The Sportsman. Al Ahly News and Scores ESPN. Super Cup Match either for Al Ahly vs Zamalek February. Al Ahly Egypt statistics table results fixtures. Al-Ahly Egyptian professional football soccer club based in Cairo. Have slowly seen El Ahly live law now Table section Egyptian Premier League 2021 club. CAF Champions League Live Streaming and TV Listings Live. The Egyptian League now called the Egyptian Premier League began once the 19449. Al-Duhail Al Ahly 0 1 0402 W EGYPTPremier League Pyramids Al Ahly. Mamelodi Sundowns FC is now South African football club based in Pretoria. Egypt Super Cup TV Channels Match Information League Table but Head-to-Head Results Al Ahly Last 5 Games Zamalek Last 5 Games. General league ranking table after Al-Ahly draw against. StreaMing Al Ahly vs El-Entag El-Harby Live Al Ahly vs El. Al Ahly move finally to allow of with table EgyptToday. Despite this secure a torrid opening 20 minutes the Cairo giants held and. CAF Champions League Onyango Lwanga and Ochaya star. 2 Al Ahly Cairo 9 6 3 0 15 21 3 Al Masry 11 5 5 1 9 20 4 Ceramica Cleopatra 12 5 4 3 4 19 5 El Gouna FC 12 5 4 3 4 19 6 Al Assiouty 12 4 6. -

“How Egypt's Soccer Fans Became Enemies of the State.” by Ishaan

“How Egypt’s Soccer Fans Became Enemies of the State.” By Ishaan Tharoor. Washington Post. Feb. 9, 2015. An Ultras White Knights soccer fan cries during a match between Egyptian Premier League clubs Zamalek and ENPPI at the Air Defense Stadium in a suburb east of Cairo, Egypt, Feb. 8, 2015. (Ahmed Abd El-Gwad/El Shorouk via AP) It's happened again. On Sunday, more than 20 Egyptian soccer fans were killed in an altercation with security forces outside a stadium that was hosting a game between Cairo clubs Zamalek and ENPPI. The tragic incident comes three years after the deaths of 72 Al Ahly soccer fans during a match in the city of Port Said, one of the worst disasters in the history of the sport. As they did three years ago, Egyptian authorities have suspended the league in the wake of the violence. Many of the dead reportedly belong to a hard-core group of Zamalek supporters known as the Zamalek White Knights. Egyptian officials say police fired tear gas to disperse a crowd of ticketless fans attempting to force its way into the stadium. Public prosecutors have ordered the arrest of leading Zamalek White Knights members. On their Facebook page, the White Knights accuse security forces of carrying out "a planned massacre." One prominent White Knights leader wrote in an online post that authorities had let some 5,000 fans enter a narrow enclosure and then shut them in, proceeding to lob rounds of tear gas into the massed crowd. "People died from the gas and the pushing, but they had shut the exit," wrote the leader, who goes by the online alias Yassir Miracle. -

Russia Strives to Assert Primacy, Rein in Turkish Ambitions in Syria

UK £2 Issue 189, Year 4 January 20, 2019 EU €2.50 www.thearabweekly.com Interview Recording Egypt’s minister abuses of of finance Palestinian rights Page 19 Page 13 Russia strives to assert primacy, rein in Turkish ambitions in Syria ► The withdrawal of the 2,000 American troops raises the question of which power will take over once the United States leaves. Thomas Seibert highlight Moscow’s strong reserva- tions about Turkey’s manoeuvres. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Istanbul Lavrov has said the Kremlin ex- pected the Syrian government to ussia seems determined take over territory in eastern Syria to assert its position as following the US withdrawal. He the strongest political and asserted it was necessary to fully R military player in Syria restore Syria’s sovereignty, add- while local and international pow- ing that Turkey’s plan to create a ers scramble to fill the expected buffer zone should be seen in that vacuum after the planned US with- context. drawal from the country. By sending military police to the With the US and Kurdish allies area west of Manbij in northern Syr- controlling approximately 25% of ia, Moscow made it clear that Rus- north-eastern Syria, the withdrawal sia does not intend to give Turkey a of the 2,000 American troops raises free hand in the region, said Kerim the question of which power will Has, a Moscow-based analyst of take over once the United States Russian-Turkish relations. leaves. The deployment demonstrated Turkish President Recep Tayyip “that Russia opts [for] its own pres- Erdogan told lawmakers of his rul- ence to avert Turkish demands for a ing party that he raised the possible military advancement,” Has said via creation of a “safe zone” in north- e-mail. -

The Next Next The

Cover Nov 2018.qxp_Cover.qxd 11/5/18 4:05 PM Page 1 BUSINESS MONTHLY BUSINESS MONTHLY NOT FOR SALE www.amcham.org.eg/bmonthly NOVEMBER THE NEXT MOVE THE NEXT MOVEGovernment aids struggling businesses NOVEMBER 2018 NOVEMBER ALSO INSIDE L L U.S. BUSINESS MISSION TO EGYPT L L STEELMAKERS JITTER L L TRADING WITH TURKEY TOC 18 new.qxp_TOC.qxd 11/5/18 4:15 PM Page 1 NOVEMBER 2018 V O L U M E 3 5 | I S S U E 1 1 Inside 22 Editor’s Note 24 Viewpoint 36 U.S. Business Mission to Egypt Full coverage of the panels, events, visits, and PR conferences. The Newsroom 26 In Brief An analytical view of the top monthly news Investor Focus 28 Egypt’s Steelmakers Did the global trade war impact Egypt’s steel industry? Market Watch 52 Market woes deepen © Copyright Business Monthly 2018. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced without the prior written consent of the editor. The opinions expressed in Business Monthly do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt. 18• Business Monthly - NOVEMBER 2018 TOC 18 new.qxp_TOC.qxd 11/5/18 4:15 PM Page 2 NOVEMBER 2018 V O L U M E 3 5 | I S S U E 1 1 Cover Story 30 Raising Egypt s Factories The government to financially support struggling companies Cover Design: Nessim N. Hanna Regional Focus 50 Turkey s New Trade Dynamics Potential impact of Turkey’s now cheaper commodities. At a Glance 54 Unemployment in Egypt A market overview Executive Life 56 Travel A Weekend in Beirut The Chamber 60 Events 65 Exclusive Offers 68 Media Lite An irreverent glance at the press © Copyright Business Monthly 2018. -

WORLD REPORT 2021 EVENTS of 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH 350 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10118-3299 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 2021 EVENTS OF 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH 350 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10118-3299 HUMAN www.hrw.org RIGHTS WATCH This 31st annual World Report summarizes human rights conditions in nearly 100 countries and territories worldwide in 2020. WORLD REPORT It reflects extensive investigative work that Human Rights Watch staff conducted during the year, often in close partnership with 2021 domestic human rights activists. EVENTS OF 2020 Human Rights Watch defends HUMAN the rights of people worldwide. RIGHTS WATCH We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Europe and All rights reserved. Central Asia division (then known as Helsinki Watch). Today it also Printed in the United States of America includes divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Central ISBN is 978-1-64421-028-4 Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and the United States. There are thematic divisions or programs on arms; business and human rights; Cover photo: Kai Ayden, age 7, marches in a protest against police brutality in Atlanta, children’s rights; crisis and conflict; disability rights; the environment and Georgia on May 31, 2020 following the death human rights; international justice; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and of George Floyd in police custody. transgender rights; refugee rights; and women’s rights. -

Comparative Analysis of Civil Society, Media and Conflict

This is a repository copy of Comparative analysis of civil society, media and conflict. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/117311/ Monograph: Pointer, R, Bosch, T, Chuma, W et al. (1 more author) (2016) Comparative analysis of civil society, media and conflict. Working Paper. MeCoDEM . ISSN 2057-4002 (Unpublished) ©2016 Rebecca Pointer, Tanja Bosch, Wallace Chuma, Herman Wasserman. The Working Papers in the MeCoDEM series serve to disseminate the research results of work in progress prior to publication in order to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the MeCoDEM Working Papers series does not constitute publication and should not limit publication in any other venue. Copyright remains with the authors. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request.