The New Testament Was Originally Written in Greek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

The Poetry of the Damascus Document

The Poetry of the Damascus Document by Mark Boyce Ph.D. University of Edinburgh 1988 For Carole. I hereby declare that the research undertaken in this thesis is the result of my own investigation and that it has been composed by myself. No part of it has been previously published in any other work. ýzýa Get Acknowledgements I should begin by thanking my financial benefactors without whom I would not have been able to produce this thesis - firstly Edinburgh University who initially awarded me a one year postgraduate scholarship, and secondly the British Academy who awarded me a further two full year's scholarship and in addition have covered my expenses for important study trips. I should like to thank the Geniza Unit of the Cambridge University Library who gave me access to the original Cairo Document fragments: T-S 10 K6 and T-S 16-311. On the academic side I must first and foremost acknowledge the great assistance and time given to me by my supervisor Prof. J. C.L. Gibson. In addition I would like to thank two other members of the Divinity Faculty, Dr. B.Capper who acted for a time as my second supervisor, and Dr. P.Hayman, who allowed me to consult him on several matters. I would also like to thank those scholars who have replied to my letters. Sa.. Finally I must acknowledge the use of the IM"IF-LinSual 10r package which is responsible for the interleaved pages of Hebrew, and I would also like to thank the Edinburgh Regional Computing Centre who have answered all my computing queries over the last three years and so helped in the word-processing of this thesis. -

High Priests

High Priests The Chronology of the High Priests power. He died, and his brother Alexander was his heir. 1st high priest – Aaron Alexander was high priest and king for 27 years, 2nd – one of Aaron’s sons and just before he died, he gave his wife, Alexan- At this time, high priests served for life, and the dra, the authority to appoint the next high priest. position was usually passed from father to son. Alexandra gave the high priesthood to Hyrcanus, From the time of Aaron until Solomon the King but she kept the throne for herself, ruled for nine was 612 years. During this time there were 13 high years, and died. priests. Average term – 47 years. After her death, Hyrcanus’ brother, another Aristo- From Solomon until the Babylonian captivity bulus, fought against him and took over both the kingship and high priesthood. But after a little 466 years and 6 months; 18 high priests; average more than three years, the Roman legions under term 26 years. Pompey took Jerusalem by force, put Aristobulus Josadek was high priest when the captivity began, and his children in bondage and sent them to Rome. and he was high priest during part of the captiv- Pompey restored the high priesthood to Hyrcanus ity. His son Jesus, was high priest when the people and appointed him governor. However, he was not were allowed to go back to the land. allowed to call himself king. From the captivity until Antiochus Eupator So Hyrcanus ruled, in addition to his first nine years, another 24 years. -

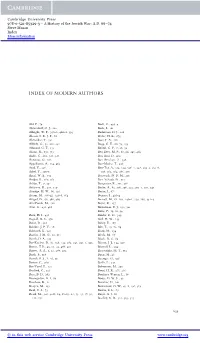

Index of Modern Authors

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85329-3 - A History of the Jewish War: A.D. 66–74 Steve Mason Index More information INDEX OF MODERN AUTHORS Ahl, F., 74 Beck, C., 493–4 Ahrensdorf, O. J., 221 Beck, I., 101 Albright, W. F., 396–8, 400–1, 593 Bederman, D. J., 220 Alcock, S. E., J. F., 60 Beebe, H. K., 274 Alexandre, Y., 341 Beer, F. A., 218 Alföldy, G., 35, 216, 241 Begg, C. T., 60, 74, 133 Allmand, C. T., 171 Bellori, G. P., 8, 26, 30 Alston, R., 139, 313 Ben Zeev, M. P., 68, 90, 248, 460 Ando, C., 260, 326, 328 Ben-Ami, D., 460 Antonius, G., 262 Ben-Avraham, Z., 398 Appelbaum, A., 154, 462 Ben-Moshe, T., 336 Arad, Y., 538 Ben-Tor, A., 514, 524, 526–7, 548, 550–3, 555–6, Arbel, Y., 350–1 558, 562, 564, 566, 571 Arnal, W. E., 339 Bentwich, N. D. M., 201 Arubas, B., 560, 565 Ben-Yehuda, N., 514 Ashby, T., 7, 39 Bergmeier, R., 131, 458 Atkinson, K., 279, 570 Berlin, A., 65, 136, 206, 225, 230–1, 339, 349 Attridge, H. W., 60, 339 Berlin, I., 67 Aviam, M., 338–41, 345–8, 364 Bernays, J., 491–4 Avigad, N., 68, 466, 469 Bernett, M., 61, 203, 240–1, 259, 266, 342–3 Avi-Yonah, M., 526 Beyer, K., 157 Avni, G., 458, 466 Bickerman, E. J., 232, 301 Bilde, P., 19, 60, 94 Bach, H. I., 491 Binder, D. D., 349 Bagnall, R. S., 470 Bird, H. W., 244 Bahat, D., 468 Birley, E., 167 Balsdon, J. -

Sample PDF Volumes

Copyright © 2013 by John Argubright Bible Believer’s Archaeology Volume 1 Historical Evidence That Proves the Bible by John Argubright Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-0-9792148-0-6 (3rd Edition) (Previously 1rst edition ISBN 1-57502-502-7) 1997 (Previously 2nd edition ISBN 1-591604-05-2) 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher. Unless otherwise indicated, Bible quotations are taken from The Holy Bible, New King James Version. Copyright © 1962 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Also quoted: New International Version Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Copyright © 1986 Zondervan Publishing House This book is copyrighted to protect its misuse and to safeguard the rights of any author, publisher, or individual whose data may have been used in research for this book and to preserve the integrity of quotes from historical sources. The majority of the historical quotes used in this book were re- translated by the author in an effort to not infringe upon the copyright of others and to protect the authors and publishers of the original source translations. This book as well as our second and third volumes in the series may be ordered at “BibleHistory.net” as well as from other major online book distributors. FOUR THINGS GOD WANTS YOU TO KNOW 1. You are a sinner and cannot save yourself. For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. Romans 3:23 2. God loves and values you so much, He made a way for you to be saved. -

Philo of Alexandria Studies in Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria Studies in Philo of Alexandria Edited by Francesca Calabi and Robert Berchman Editorial Board Kevin Corrigan (Emory University) Louis H. Feldman (Yeshiva University, New York) Mireille Hadas-Lebel (La Sorbonne, Paris) Carlos Lévy (La Sorbonne, Paris) Maren Niehoff (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Tessa Rajak (University of Reading) Roberto Radice (Università Cattolica, Milano) Esther Starobinski-Safran (Université de Genève) Lucio Troiani (Universita’ di Pavia) VOLUME 7 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/philo Philo of Alexandria A Thinker in the Jewish Diaspora By Mireille Hadas-Lebel Translated by Robyn Fréchet LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Originally published as Philon d’Alexandrie un penseur en diaspora by Mireille Hadas-Lebel ©Librarie Arthème Fayard, 2003. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hadas-Lebel, Mireille. [Philon d’Alexandrie. English] Philo of Alexandria : a thinker in the Jewish diaspora / by Mireille Hadas-Lebel ; translated by Robyn Frechet. p. cm. — (Studies in Philo of Alexandria ; 7) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20948-0 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-23237-2 (e-book) (print) 1. Philo, of Alexandria. 2. Alexandria (Egypt)—Civilization. 3. Judaism and philosophy. 4. Hellenism. I. Fr?chet, Robyn, translator. II. Title. B689.Z7H3413 2012 181’.06—dc23 2012017637 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.nl/brill-typeface. ISSN 1543-995x ISBN 9789004209480 (hardback) ISBN 9789004232372 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

King Herod: a Persecuted Persecutor

KING HEROD: A PERSECUTED PERSECUTOR A CASE STUDY IN PSYCHOHISTORY AND PSYCHOBIOGRAPHY BY ARYEH KASHER IN COLLABORATION WITH ELIEZER WITZTUM TRANSLATED BY KAREN GOLD WALTER DE GRUYTER • BERLIN • NEW YORK Table of Contents Foreword xi Preface xvii Acknowledgements xix Introduction Methodology 1 Psychopathological Aspects of Herod 12 Chapter 1 Residues of Childhood in the Late Hasmonaean Period (73/72-63 BCE) Herod's Origins and Their Impact on His Personality 18 Political Ambitions since Childhood 24 Chapter 2 Adolescence in the Shadow of the Roman Conquest (63-42 BCE) Consolidation of Power in the House of Antipater 34 Appointment as Strategos of Galilee, and Trial before San- hedrin (47-46 BCE) 39 Political Acrobatics Following the Murder of Julius Caesar 45 Betrothal to Mariamme the Hasmonaean (42 BCE) 51 Chapter 3 From the Utmost Depths to the Conquest of Jerusalem (41-37 BCE) In the Shadow of the Parthian Invasion 57 The Rift between Herod and the Nabateans 64 Herod is Crowned in Rome as King of Judaea 65 The War against Mattathias Antigonus 72 vi Table of Contents Chapter 4 Herod in the First Year of His Reign (37 BCE) Conquest of Jerusalem 84 Execution of Mattathias Antigonus 86 Marriage to Mariamme the Hasmonaean 92 New Arrangements in Conquered Jerusalem 99 Chapter 5 Roots and Ramifications of the Hasmonaean Trauma (37-34 BCE) The Problem of John Hyrcanus II 101 The Murder of Aristobulus III 104 Alexandra and Cleopatra's Influence on Antony Regarding the Laodicea Meeting 113 Construction of Masada as a Palace-Fortress 116 The First -

Simon Peter's Names in Jewish Sources

journal of jewish studies, vol. lv, no. 1, spring 2004 Simon Peter’s Names in Jewish Sources Markus Bockmuehl Faculty of Divinity, University of Cambridge imon, Bar Yonah,Peter, Cephas: what, if anything, might St Peter’s names S have meant to Palestinian Jews in late antiquity? On a casual approach, the pickings appear very slim indeed.1 A second look, however, suggests there may still be some interesting mileage in tracing the significance of those names during the late Second Temple and early rabbinic periods. The Talmud, to be sure, does not hold out much hope to anyone looking for knowledge of Simon Peter. While it is widely agreed to hint at Jesus and Jewish Christianity on a number of occasions, there is really only one passage that explicitly discusses the immediate disciples of Jesus.2 This is the famous censored baraita in b. Sanhedrin 43a, missing from standard early printed edi- tions but widely accepted as part of the definitive text: ‘Our Rabbis taught: Yeshu had five disciples, Mattai, Nakai, Nezer, Buni and Todah.’ The text continues by offering an extended midrashic word play on why all five deserve tobeexecuted....3 We cannot be certain that this tradition of five disciples is of Tannaitic origin, or indeed whether this number derives from a desire either to legitimate or to undermine Jesus. It appears to be stylised in keeping with a similar traditional number of five disciples for both Yoh. anan ben Zakkai and 1 Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Durham meeting of the Society for New Testament Studies (2002) and to the senior New Testament Seminar at the University of Oxford (2003). -

Josephus' Jewish War and the Causes of the Jewish Revolt: Re-Examining Inevitability

JOSEPHUS’ JEWISH WAR AND THE C AUSES OF THE JEWISH REVOLT: RE-EXAMINING INEVITABILITY Javier Lopez, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2013 APPROVED: Christopher J. Fuhrmann, Major Professor Ken Johnson, Committee Member Walt Roberts, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Lopez, Javier. Josephus’ Jewish War and the Causes of the Jewish Revolt: Re-Examining Inevitability. Master of Arts (History), December 2013, 85 pp., 3 tables, 3 illustrations, bibliography, 60 titles. The Jewish revolt against the Romans in 66 CE can be seen as the culmination of years of oppression at the hands of their Roman overlords. The first-century historian Josephus narrates the developments of the war and the events prior. A member of the priestly class and a general in the war, Josephus provides us a detailed account that has long troubled historians. This book was an attempt by Josephus to explain the nature of the war to his primary audience of predominantly angry and grieving Jews. The causes of the war are explained in different terms, ranging from Roman provincial administration, Jewish apocalypticism, and Jewish internal struggles. The Jews eventually reached a tipping point and engaged the Romans in open revolt. Josephus was adamant that the origin of the revolt remained with a few, youthful individuals who were able to persuade the country to rebel. This thesis emphasizes the causes of the war as Josephus saw them and how they are reflected both within The Jewish War and the later work Jewish Antiquities. -

Flavius Josephus Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism

Flavius Josephus Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism Editor Benjamin G. Wright, III Department of Religion Studies, Lehigh University Associate Editors Florentino García Martínez Qumran Institute, University of Groningen Hindy Najman Department and Centre for the Study of Religion, University of Toronto Advisory Board g. bohak – j.j. collins – j. duhaime – p.w. van der horst – a.k. petersen – m. popoviĆ – j.t.a.g.m. van ruiten – j. sievers – g. stemberger – e.j.c. tigchelaar – j. magliano-tromp VOLUME 146 Flavius Josephus Interpretation and History Edited by Jack Pastor, Pnina Stern, and Menahem Mor LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flavius Josephus : interpretation and history / edited by Jack Pastor, Pnina Stern, and Menahem Mor. p. cm. — (Supplements to the Journal for the study of Judaism ; v. 146) “This volume was born of an international conference entitled ‘Making history: Josephus and historical method’ held at the University of Haifa from 2–6 July, 2006”—Introd. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-19126-6 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Josephus, Flavius—Congresses. 2. Jews—History—168 B.C.–135 A.D.—Historiography—Congresses. I. Pastor, Jack, 1947– II. Stern, Pnina. III. Mor, Menahem. DS115.9.J6F54 2011 933.0072’02—dc22 2010049093 ISSN 1384-2161 ISBN 978 90 04 19126 6 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Cline Family and Beyond

The Family Volume II Appendices ii Contents Volume 11 Appendix A - Ancient Branches, 1 Britons, Franks, Hebrews, Scandinavian, Scythian, Sicambrian Appendix B - Direct Ancestral Links to the Ancient Past, 19 Norman-English, Celtic-French, Anglo-Saxon, Mayflower, Hohenstauffen-English, Hebrew Appendix C - Virginia Ligons, 51 Documents, Extended Families, “From Jackson to Vicksburg 1861-1865 - Memories of the War Between the States” Appendix D - Scottish Clan Connections, 85 Member Clans of the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs: Bruce, Campbell, Drummond, Dunbar, Gordon, Graham, Hamilton, Hanna, Hay, Home, Keith, Ker, Leslie, Lindsay, Lyon, MacDonald, Montgomery, Murray, Ross,, Scott, Sempill, Sinclair, Stuart of Bute, Sutherland, Wallace. The Armigerous Clans and Families of Sc otland: Armstrong, Baillie, Douglas, Fleming, Hepburn, Livingston, Lundin, Muir, Seton, Somerville, Stewart (Royal), Stewart of Appin, Stewart of Atholl. Other Clan/Sept Connec tions: Angus, Barclay, Galloway, Haye, Knights Templar (Dress/Huntimg), Roslyn Chaple, Royal Stewart Appendix E - Magna Charta Barons, 131 The Baronage of the Magna Charta & Biographies: William d’Albini (Aubigny), Roger Bigod, Hugh Bigod, Henry de Bohun, Richard de Clare, Gilbert de Clare, John FitzRobert, Robert FitzWalter, William de Fortibus, William de Hardell (Mayor of London), William de Huntingfield, William de Lanvallei, John de Lacie, William Malet, Geoffrey de Mandeville, William Marshall Jr., Roger de Montbegon, Richard de Montifichet, Roger de Mobray, William de Mowbray, Saire -

The Temple and Early Christian Identity

Continuity and Discontinuity: The Temple and Early Christian Identity by Timothy Scott Wardle Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Joel Marcus, Supervisor ___________________________ Eric Meyers ___________________________ Lucas Van Rompay ___________________________ Christopher Rowe Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 ABSTRACT Continuity and Discontinuity: The Temple and Early Christian Identity by Timothy Scott Wardle Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Joel Marcus, Supervisor ___________________________ Eric Meyers ___________________________ Lucas Van Rompay ___________________________ Christopher Rowe An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2008 Copyright by Timothy Scott Wardle 2008 Abstract In Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, he asks the readers this question: “Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s spirit dwells in you?” (1 Cor 3:16). Although Paul is the earliest Christian writer to explicitly identify the Christian community with the temple of God, this correlation is not a Pauline innovation. Indeed, this association between the community and the temple first appears in pre-Pauline Christianity (see Gal 2:9) and is found in many layers of first-century Christian tradition. Some effects of this identification are readily apparent, as the equation of the Christian community with a temple (1) conveyed the belief that the presence of God was now present in this community in a special way, (2) underlined the importance of holy living, and (3) provided for the metaphorical assimilation of Gentiles into the people of God.