The Poetry of the Damascus Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank Moore Cross's Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Classics and Religious Studies Department 2014 Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Crawford, Sidnie White, "Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls" (2014). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 127. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Frank Moore Cross’s Contribution to the Study of the Dead Sea Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford This paper examines the impact of Frank Moore Cross on the study of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Since Cross was a member of the original editorial team responsible for publishing the Cave 4 materials, his influence on the field was vast. The article is limited to those areas of Scrolls study not covered in other articles; the reader is referred especially to the articles on palaeography and textual criticism for further discussion of Cross’s work on the Scrolls. t is difficult to overestimate the impact the discovery They icturedp two columns of a manuscript, columns of of the Dead Sea Scrolls had on the life and career of the Book of Isaiah . -

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

Worthy of Another Look: the Great Isaiah Scroll and the Book of Mormon

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 20 Number 2 Article 7 2011 Worthy of Another Look: The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Book of Mormon Donald W. Perry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Perry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D. (2011) "Worthy of Another Look: The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Book of Mormon," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 20 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol20/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Worthy of Another Look: The Great Isaiah Scroll and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Donald W. Parry and Stephen D. Ricks Reference Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20/2 (2011): 78–80. ISSN 1948-7487 (print), 2167-7565 (online) Abstract Numerous differences exist between the Isaiah pas- sages in the Book of Mormon and the corresponding passages in the King James Version of the Bible. The Great Isaiah Scroll supports several of these differences found in the Book of Mormon. Five parallel passages in the Isaiah scroll, the Book of Mormon, and the King James Version of the Bible are compared to illus- trate the Book of Mormon’s agreement with the Isaiah scroll. WORTHY OF ANOTHER LOOK THE GREAT ISAIAH SCROLL AND THE BOOK OF MORMON DONALD W. -

The Concept of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate Faculty Publications and Presentations School 2010 The onceptC of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant Jintae Kim Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Jintae, "The oncC ept of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant" (2010). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 374. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/374 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate School at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [JGRChJ 7 (2010) 98-111] THE CONCEPT OF ATONEMENT IN THE QUMRAN LITERatURE AND THE NEW COVENANT Jintae Kim Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, Lynchburg, VA Since their first discovery in 1947, the Qumran Scrolls have drawn tremendous scholarly attention. One of the centers of the early discussion was whether one could find clues to the origin of Christianity in the Qumran literature.1 Among the areas of discussion were the possible connections between the Qumran literature and the New Testament con- cept of atonement.2 No overall consensus has yet been reached among scholars concerning this issue. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2000 The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints Donald W. Parry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Parry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D., "The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints" (2000). Maxwell Institute Publications. 25. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface What is the Copper Scroll? Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contain lost books of the Bible? Did John the Baptist study with the people of Qumran? What is the Temple Scroll? What about DNA research and the scrolls? We have responded to scores of such questions on many occasions—while teaching graduate seminars and Hebrew courses at Brigham Young University, presenting papers at professional symposia, and speaking to various lay audiences. These settings are always positive experiences for us, particularly because they reveal that the general membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a deep interest in the scrolls and other writings from the ancient world. The nonbiblical Dead Sea Scrolls are of great import because they shed much light on the cultural, religious, and political position of some of the Jews who lived shortly before and during the time of Jesus Christ. -

Pesher and Hypomnema

Pesher and Hypomnema Pieter B. Hartog - 978-90-04-35420-3 Downloaded from Brill.com12/17/2020 07:36:03PM via free access Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah Edited by George J. Brooke Associate Editors Eibert J.C. Tigchelaar Jonathan Ben-Dov Alison Schofield VOLUME 121 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/stdj Pieter B. Hartog - 978-90-04-35420-3 Downloaded from Brill.com12/17/2020 07:36:03PM via free access Pesher and Hypomnema A Comparison of Two Commentary Traditions from the Hellenistic-Roman Period By Pieter B. Hartog LEIDEN | BOSTON Pieter B. Hartog - 978-90-04-35420-3 Downloaded from Brill.com12/17/2020 07:36:03PM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hartog, Pieter B, author. Title: Pesher and hypomnema : a comparison of two commentary traditions from the Hellenistic-Roman period / by Pieter B. Hartog. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2017] | Series: Studies on the texts of the Desert of Judah ; volume 121 | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Midrash and Pesher-Their Significance to T

Midrash and Pesher: Their Significance to the Intertextuality Debate By Dan Fabricatore INTRODUCTION The discovery of the Qumran scrolls has shed much light as to how the scholars of the 1st century viewed the Old Testament Scriptures. In these scrolls we find hermeneutical techniques common to that day that some hold may have influenced the New Testament authors as they themselves used Old Testament passages for their own purposes. This presentation will attempt to look at concepts of midrash and pesher, their use in the New Testament, and their relevance to New Testament study today. TERMINOLOGY Trying to define midrash and pesher is akin to a maze. Just when you think you have a handle on the thing, you are afforded several new ways in which to go.1 Midrash The term midrash is a Hebrew noun (midrāš; pl. midrāšîm) derived from the verb dāraš which means “to search” (i.e. for an answer). Therefore midrash means “inquiry,” “examination” or “commentary.”2 Ezra 7:10 is the first use where a written text is the object of dāraš. 10 For Ezra had set his heart to study the law of the LORD, and to practice it, and to teach His statutes and ordinances in Israel. 10 T#o(jlaw; hwFhy: trawTo-t)e $wrod;li wbobFl; 4ykihe )rFz;(e yKi S .+PF$;miW qxo l)erF#;yiB; dMelal;W Midrash has a variety of meanings and uses in the Qumran literature. It is used to refer to “judicial investigation, study of the law, and interpretation.”3 However the main use at Qumran 1 This first presentation is somewhat purposely vague. -

High Priests

High Priests The Chronology of the High Priests power. He died, and his brother Alexander was his heir. 1st high priest – Aaron Alexander was high priest and king for 27 years, 2nd – one of Aaron’s sons and just before he died, he gave his wife, Alexan- At this time, high priests served for life, and the dra, the authority to appoint the next high priest. position was usually passed from father to son. Alexandra gave the high priesthood to Hyrcanus, From the time of Aaron until Solomon the King but she kept the throne for herself, ruled for nine was 612 years. During this time there were 13 high years, and died. priests. Average term – 47 years. After her death, Hyrcanus’ brother, another Aristo- From Solomon until the Babylonian captivity bulus, fought against him and took over both the kingship and high priesthood. But after a little 466 years and 6 months; 18 high priests; average more than three years, the Roman legions under term 26 years. Pompey took Jerusalem by force, put Aristobulus Josadek was high priest when the captivity began, and his children in bondage and sent them to Rome. and he was high priest during part of the captiv- Pompey restored the high priesthood to Hyrcanus ity. His son Jesus, was high priest when the people and appointed him governor. However, he was not were allowed to go back to the land. allowed to call himself king. From the captivity until Antiochus Eupator So Hyrcanus ruled, in addition to his first nine years, another 24 years. -

Preliminary Studies in the Judaean Desert Isaiah Scrolls and Fragments

INCORPORATING SYNTAX INTO THEORIES OF TEXTUAL TRANSMISSION: PRELIMINARY STUDIES IN THE JUDAEAN DESERT ISAIAH SCROLLS AND FRAGMENTS by JAMES M. TUCKER A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Biblical Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Martin G. Abegg Jr., Ph.D.; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Dirk Büchner, Ph.D.; Second Reader TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY Date (August, 2014) © James M. Tucker TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations and Sigla i Abstract iv Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.0. Introduction: A Statement of the Problem 1 1.1. The Goal and Scope of the Thesis 5 Chapter 2: Methodological Issues in the Transmission Theories of the Hebrew Bible: The Need for Historical Linguistics 7 2.0. The Use of the Dead Sea Scrolls Evidence for Understanding The History of ! 7 2.1. A Survey and Assessment of Transmission Theories 8 2.1.1. Frank Moore Cross and the Local Text Theory 10 2.1.1.1. The Central Premises of the Local Text Theory 11 2.1.1.2. Assessment of the Local Text Theory 14 2.1.2. Shemaryahu Talmon and The Multiple Text Theory 16 2.1.2.1. The Central Premises of the Multiple Texts Theory 17 2.1.2.2. Assessment of Multiple Text Theory 20 2.1.3. Emanuel Tov and The Non-Aligned Theory 22 2.1.3.1 The Central Premises of the Non-Aligned Theory 22 2.1.3.2. Assessment of the Non-Aligned Theory 24 2.1.4. -

Index of Modern Authors

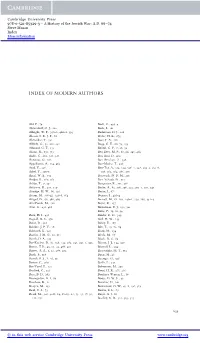

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85329-3 - A History of the Jewish War: A.D. 66–74 Steve Mason Index More information INDEX OF MODERN AUTHORS Ahl, F., 74 Beck, C., 493–4 Ahrensdorf, O. J., 221 Beck, I., 101 Albright, W. F., 396–8, 400–1, 593 Bederman, D. J., 220 Alcock, S. E., J. F., 60 Beebe, H. K., 274 Alexandre, Y., 341 Beer, F. A., 218 Alföldy, G., 35, 216, 241 Begg, C. T., 60, 74, 133 Allmand, C. T., 171 Bellori, G. P., 8, 26, 30 Alston, R., 139, 313 Ben Zeev, M. P., 68, 90, 248, 460 Ando, C., 260, 326, 328 Ben-Ami, D., 460 Antonius, G., 262 Ben-Avraham, Z., 398 Appelbaum, A., 154, 462 Ben-Moshe, T., 336 Arad, Y., 538 Ben-Tor, A., 514, 524, 526–7, 548, 550–3, 555–6, Arbel, Y., 350–1 558, 562, 564, 566, 571 Arnal, W. E., 339 Bentwich, N. D. M., 201 Arubas, B., 560, 565 Ben-Yehuda, N., 514 Ashby, T., 7, 39 Bergmeier, R., 131, 458 Atkinson, K., 279, 570 Berlin, A., 65, 136, 206, 225, 230–1, 339, 349 Attridge, H. W., 60, 339 Berlin, I., 67 Aviam, M., 338–41, 345–8, 364 Bernays, J., 491–4 Avigad, N., 68, 466, 469 Bernett, M., 61, 203, 240–1, 259, 266, 342–3 Avi-Yonah, M., 526 Beyer, K., 157 Avni, G., 458, 466 Bickerman, E. J., 232, 301 Bilde, P., 19, 60, 94 Bach, H. I., 491 Binder, D. D., 349 Bagnall, R. S., 470 Bird, H. W., 244 Bahat, D., 468 Birley, E., 167 Balsdon, J. -

Sample PDF Volumes

Copyright © 2013 by John Argubright Bible Believer’s Archaeology Volume 1 Historical Evidence That Proves the Bible by John Argubright Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-0-9792148-0-6 (3rd Edition) (Previously 1rst edition ISBN 1-57502-502-7) 1997 (Previously 2nd edition ISBN 1-591604-05-2) 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher. Unless otherwise indicated, Bible quotations are taken from The Holy Bible, New King James Version. Copyright © 1962 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Also quoted: New International Version Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Copyright © 1986 Zondervan Publishing House This book is copyrighted to protect its misuse and to safeguard the rights of any author, publisher, or individual whose data may have been used in research for this book and to preserve the integrity of quotes from historical sources. The majority of the historical quotes used in this book were re- translated by the author in an effort to not infringe upon the copyright of others and to protect the authors and publishers of the original source translations. This book as well as our second and third volumes in the series may be ordered at “BibleHistory.net” as well as from other major online book distributors. FOUR THINGS GOD WANTS YOU TO KNOW 1. You are a sinner and cannot save yourself. For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. Romans 3:23 2. God loves and values you so much, He made a way for you to be saved. -

Philo of Alexandria Studies in Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria Studies in Philo of Alexandria Edited by Francesca Calabi and Robert Berchman Editorial Board Kevin Corrigan (Emory University) Louis H. Feldman (Yeshiva University, New York) Mireille Hadas-Lebel (La Sorbonne, Paris) Carlos Lévy (La Sorbonne, Paris) Maren Niehoff (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem) Tessa Rajak (University of Reading) Roberto Radice (Università Cattolica, Milano) Esther Starobinski-Safran (Université de Genève) Lucio Troiani (Universita’ di Pavia) VOLUME 7 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/philo Philo of Alexandria A Thinker in the Jewish Diaspora By Mireille Hadas-Lebel Translated by Robyn Fréchet LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Originally published as Philon d’Alexandrie un penseur en diaspora by Mireille Hadas-Lebel ©Librarie Arthème Fayard, 2003. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hadas-Lebel, Mireille. [Philon d’Alexandrie. English] Philo of Alexandria : a thinker in the Jewish diaspora / by Mireille Hadas-Lebel ; translated by Robyn Frechet. p. cm. — (Studies in Philo of Alexandria ; 7) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20948-0 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-23237-2 (e-book) (print) 1. Philo, of Alexandria. 2. Alexandria (Egypt)—Civilization. 3. Judaism and philosophy. 4. Hellenism. I. Fr?chet, Robyn, translator. II. Title. B689.Z7H3413 2012 181’.06—dc23 2012017637 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.nl/brill-typeface. ISSN 1543-995x ISBN 9789004209480 (hardback) ISBN 9789004232372 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands.