Herod the Great Additional Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

Outlines of Bible Study

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Stone-Campbell Books Stone-Campbell Resources 1950 Outlines of Bible Study G. Dallas Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Smith, G. Dallas, "Outlines of Bible Study" (1950). Stone-Campbell Books. 439. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books/439 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Stone-Campbell Resources at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stone-Campbell Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. G. Dallas Smith Outlines of Bible Study FOR USE IN QIBLE DRILLS, BIBLE READINGS, BIBLE CLASSES, PRAYER MEETINGS, AND HOME STUDY (Revbed and Enl al"ll'ed) BY G. DALLAS SMITH Murfree sboro, Teaa. * * * Order From : A. C. C. Students' Exchang e Statio n A Abil ene, Texas PREFACE Outlines of Bible Study is not a commentary in any sense of the word. It contains but few comments. It is not " literature" in the sense in which many object to literature. It docs not study the lessons for you, but rather guides you in an intelligent study of the Bible itself. It is just what its name implie s-outlin es of Bible study. It simply outlines your Bible study, making it possible for you to study it sys tematically and profitabl y. The questions following e!lch outline direct the student, with but few exceptions~ to the Bible itself for his answers. This forces him to "search the Scriptures" diligently to find answers to the questions, and leaves him free to frame his answers in his own language. -

The Poetry of the Damascus Document

The Poetry of the Damascus Document by Mark Boyce Ph.D. University of Edinburgh 1988 For Carole. I hereby declare that the research undertaken in this thesis is the result of my own investigation and that it has been composed by myself. No part of it has been previously published in any other work. ýzýa Get Acknowledgements I should begin by thanking my financial benefactors without whom I would not have been able to produce this thesis - firstly Edinburgh University who initially awarded me a one year postgraduate scholarship, and secondly the British Academy who awarded me a further two full year's scholarship and in addition have covered my expenses for important study trips. I should like to thank the Geniza Unit of the Cambridge University Library who gave me access to the original Cairo Document fragments: T-S 10 K6 and T-S 16-311. On the academic side I must first and foremost acknowledge the great assistance and time given to me by my supervisor Prof. J. C.L. Gibson. In addition I would like to thank two other members of the Divinity Faculty, Dr. B.Capper who acted for a time as my second supervisor, and Dr. P.Hayman, who allowed me to consult him on several matters. I would also like to thank those scholars who have replied to my letters. Sa.. Finally I must acknowledge the use of the IM"IF-LinSual 10r package which is responsible for the interleaved pages of Hebrew, and I would also like to thank the Edinburgh Regional Computing Centre who have answered all my computing queries over the last three years and so helped in the word-processing of this thesis. -

Political, Ethno-Religious, and Theological

The Collective Designation of Christ-Followers as Ekkl ēsiai BEFORE ‘CHURCH’: POLITICAL, ETHNO-RELIGIOUS, AND THEOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE COLLECTIVE DESIGNATION OF PAULINE CHRIST- FOLLOWERS AS EKKL ĒSIAI By RALPH JOHN KORNER, M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Ralph John Korner, January 2014 Ph.D. Thesis – R. J. Korner; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2014) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Before ‘Church’: Political, Ethno-Religious, and Theological Implications of the Collective Designation of Pauline Christ-Followers as Ekkl ēsiai AUTHOR: Ralph John Korner SUPERVISOR: Anders Runesson NUMBER OF PAGES: xiv, 394. ii Ph.D. Thesis – R. J. Korner; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Before ‘Church’: Political, Ethno-Religious, and Theological Implications of the Collective Designation of Pauline Christ-Followers as Ekkl ēsiai In this study I situate socio-historically the adoption of the term ekkl ēsia as a permanent identity by some groups of early Christ-followers. Given pre-existing usages of the word ekkl ēsia in Greco-Roman and Jewish circles, I focus on three investigative priorities: What source(s) lie(s) behind the permanent self-designation of some Christ- followers as an ekkl ēsia ? What theological need(s) did that collective identity meet? What political and ethno-religious ideological end(s) did the appropriation of ekkl ēsia as a sub-group identity serve? In addressing these questions, particularly in relation to Paul’s use of the word ekkl ēsia , I contribute to at least three areas of ekkl ēsia research. -

Josephus Writings Outline

THE WARS OF THE JEWS OR THE HISTORY OF THE DESTRUCTION OF JERUSALEM – BOOK I CONTAINING FROM THE TAKING OF JERUSALEM BY ANTIOCHUS EPIPHANES TO THE DEATH OF HEROD THE GREAT. (THE INTERVAL OF 177 YEARS) CHAPTER 1: HOW THE CITY JERUSALEM WAS TAKEN, AND THE TEMPLE PILLAGED [BY ANTIOCHUS EPIPHANES]; AS ALSO CONCERNING THE ACTIONS OF THE MACCABEES, MATTHIAS AND JUDAS; AND CONCERNING THE DEATH OF JUDAS. CHAPTER 2: CONCERNING THE SUCCESSORS OF JUDAS; WHO WERE JONATHAN AND SIMON, AND JOHN HYRCANUS? CHAPTER 3: HOW ARISTOBULUS WAS THE FIRST THAT PUT A DIADEM ABOUT HIS HEAD; AND AFTER HE HAD PUT HIS MOTHER AND BROTHER TO DEATH, DIED HIMSELF, WHEN HE HAD REIGNED NO MORE THAN A YEAR. CHAPTER 4: WHAT ACTIONS WERE DONE BY ALEXANDER JANNEUS, WHO REIGNED TWENTY- SEVEN YEARS. CHAPTER 5: ALEXANDRA REIGNS NINE YEARS, DURING WHICH TIME THE PHARISEES WERE THE REAL RULERS OF THE NATION. CHAPTER 6: WHEN HYRCANUS WHO WAS ALEXANDER'S HEIR, RECEDED FROM HIS CLAIM TO THE CROWN ARISTOBULUS IS MADE KING; AND AFTERWARD THE SAME HYRCANUS BY THE MEANS OF ANTIPATER; IS BROUGHT BACK BY ABETAS. AT LAST POMPEY IS MADE THE ARBITRATOR OF THE DISPUTE BETWEEN THE BROTHERS. CHAPTER 7: HOW POMPEY HAD THE CITY OF JERUSALEM DELIVERED UP TO HIM BUT TOOK THE TEMPLE BY FORCE. HOW HE WENT INTO THE HOLY OF HOLIES; AS ALSO WHAT WERE HIS OTHER EXPLOITS IN JUDEA. CHAPTER 8: ALEXANDER, THE SON OF ARISTOBULUS, WHO RAN AWAY FROM POMPEY, MAKES AN EXPEDITION AGAINST HYRCANUS; BUT BEING OVERCOME BY GABINIUS HE DELIVERS UP THE FORTRESSES TO HIM. -

High Priests

High Priests The Chronology of the High Priests power. He died, and his brother Alexander was his heir. 1st high priest – Aaron Alexander was high priest and king for 27 years, 2nd – one of Aaron’s sons and just before he died, he gave his wife, Alexan- At this time, high priests served for life, and the dra, the authority to appoint the next high priest. position was usually passed from father to son. Alexandra gave the high priesthood to Hyrcanus, From the time of Aaron until Solomon the King but she kept the throne for herself, ruled for nine was 612 years. During this time there were 13 high years, and died. priests. Average term – 47 years. After her death, Hyrcanus’ brother, another Aristo- From Solomon until the Babylonian captivity bulus, fought against him and took over both the kingship and high priesthood. But after a little 466 years and 6 months; 18 high priests; average more than three years, the Roman legions under term 26 years. Pompey took Jerusalem by force, put Aristobulus Josadek was high priest when the captivity began, and his children in bondage and sent them to Rome. and he was high priest during part of the captiv- Pompey restored the high priesthood to Hyrcanus ity. His son Jesus, was high priest when the people and appointed him governor. However, he was not were allowed to go back to the land. allowed to call himself king. From the captivity until Antiochus Eupator So Hyrcanus ruled, in addition to his first nine years, another 24 years. -

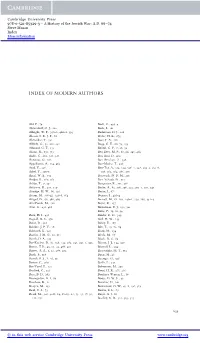

Index of Modern Authors

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85329-3 - A History of the Jewish War: A.D. 66–74 Steve Mason Index More information INDEX OF MODERN AUTHORS Ahl, F., 74 Beck, C., 493–4 Ahrensdorf, O. J., 221 Beck, I., 101 Albright, W. F., 396–8, 400–1, 593 Bederman, D. J., 220 Alcock, S. E., J. F., 60 Beebe, H. K., 274 Alexandre, Y., 341 Beer, F. A., 218 Alföldy, G., 35, 216, 241 Begg, C. T., 60, 74, 133 Allmand, C. T., 171 Bellori, G. P., 8, 26, 30 Alston, R., 139, 313 Ben Zeev, M. P., 68, 90, 248, 460 Ando, C., 260, 326, 328 Ben-Ami, D., 460 Antonius, G., 262 Ben-Avraham, Z., 398 Appelbaum, A., 154, 462 Ben-Moshe, T., 336 Arad, Y., 538 Ben-Tor, A., 514, 524, 526–7, 548, 550–3, 555–6, Arbel, Y., 350–1 558, 562, 564, 566, 571 Arnal, W. E., 339 Bentwich, N. D. M., 201 Arubas, B., 560, 565 Ben-Yehuda, N., 514 Ashby, T., 7, 39 Bergmeier, R., 131, 458 Atkinson, K., 279, 570 Berlin, A., 65, 136, 206, 225, 230–1, 339, 349 Attridge, H. W., 60, 339 Berlin, I., 67 Aviam, M., 338–41, 345–8, 364 Bernays, J., 491–4 Avigad, N., 68, 466, 469 Bernett, M., 61, 203, 240–1, 259, 266, 342–3 Avi-Yonah, M., 526 Beyer, K., 157 Avni, G., 458, 466 Bickerman, E. J., 232, 301 Bilde, P., 19, 60, 94 Bach, H. I., 491 Binder, D. D., 349 Bagnall, R. S., 470 Bird, H. W., 244 Bahat, D., 468 Birley, E., 167 Balsdon, J. -

Nickelsburg Final.Indd

1 Sects, Parties, and Tendencies Judaism of the last two centuries b.c.e. and the first century c.e. saw the devel- opment of a rich, variegated array of groups, sects, and parties. In this chapter we shall present certain of these groupings, both as they saw themselves and as others saw them. Samaritans, Hasideans, Pharisees and Sadducees, Essenes, and Therapeutae will come to our attention, as will a brief consideration of the hellenization of Judaism and appearance of an apocalyptic form of Judaism. The diversity—which is not in name only, but also in belief and practice, order of life and customary conduct, and the cultural and intellectual forms in which it was expressed—raises several questions: How did this diversity originate? What were the predominating characteristics of Judaism of that age or, indeed, were there such? Was there a Judaism or were there many Judaisms? How do rabbinic Juda- ism and early Christianity emerge from it or them? The question of origins takes us back into the unknown. The religious and social history of Judaism in the latter part of the Persian era and in the Ptolemaic age (the fourth and third centuries b.c.e.) is little documented. The Persian prov- ince of Judah was a temple state ruled by a high-priestly aristocracy. Although some of the later parts of the Bible were written then and others edited at that time, and despite some new information from the Dead Sea manuscripts, the age itself remains largely unknown. Some scholars have tried to reconstruct the history of this period by work- ing back from the conflict between Hellenism and Judaism that broke into open revolt in the early second century.1 With the conquests of Alexander the Great in 334–323 b.c.e.—and indeed, somewhat earlier—the vital and powerful culture of the Greeks and the age-old cultures of the Near East entered upon a process of contact and conflict and generated varied forms of religious synthesis and self- definition. -

Sample PDF Volumes

Copyright © 2013 by John Argubright Bible Believer’s Archaeology Volume 1 Historical Evidence That Proves the Bible by John Argubright Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-0-9792148-0-6 (3rd Edition) (Previously 1rst edition ISBN 1-57502-502-7) 1997 (Previously 2nd edition ISBN 1-591604-05-2) 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher. Unless otherwise indicated, Bible quotations are taken from The Holy Bible, New King James Version. Copyright © 1962 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Also quoted: New International Version Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Copyright © 1986 Zondervan Publishing House This book is copyrighted to protect its misuse and to safeguard the rights of any author, publisher, or individual whose data may have been used in research for this book and to preserve the integrity of quotes from historical sources. The majority of the historical quotes used in this book were re- translated by the author in an effort to not infringe upon the copyright of others and to protect the authors and publishers of the original source translations. This book as well as our second and third volumes in the series may be ordered at “BibleHistory.net” as well as from other major online book distributors. FOUR THINGS GOD WANTS YOU TO KNOW 1. You are a sinner and cannot save yourself. For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God. Romans 3:23 2. God loves and values you so much, He made a way for you to be saved. -

Judea/Israel Under the Greek Empires." Israel and Empire: a Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism

"Judea/Israel under the Greek Empires." Israel and Empire: A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism. Perdue, Leo G., and Warren Carter.Baker, Coleman A., eds. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. 129–216. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567669797.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 15:32 UTC. Copyright © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Judea/Israel under the Greek Empires* In 33130 BCE, by military victory, the Macedonian Alexander ended the Persian Empire. He defeated the Persian king Darius at Gaugamela, advanced to a welcoming Babylon, and progressed to Persepolis where he burned Xerxes palace supposedly in retaliation for Persias invasions of Greece some 150 years previously (Diodorus 17.72.1-6). Thus one empire gave way to another by a different name. So began the Greek empires that dominated Judea/Israel for the next two hundred or so years, the focus of this chapter. Is a postcolonial discussion of these empires possible and what might it highlight? Considerable dif�culties stand in the way. One is the weight of conventional analyses and disciplinary practices which have framed the discourse with emphases on the various roles of the great men, the ruling state, military battles, and Greek settlers, and have paid relatively little regard to the dynamics of imperial power from the perspectives of native inhabitants, the impact on peasants and land, and poverty among non-elites, let alone any reciprocal impact between colonizers and colon- ized. -

Mattathias Antigonus Coins - the Last Kings of the Hasmonean [email protected]

Mattathias Antigonus coins - the last kings of the Hasmonean [email protected] Zlotnik yehoshua 10.10.10 Abstract Mattathias Antigonus was the last king of the Hasmonean-Maccabean Dynasty (37-40 BC' all dates BC). Struggles and uprisings preceded his reign of the Hasmonean state, by his father Aristobulus II and his brother Alexander II for control of the Hasmonean kingdom. The three years of his reign were a turbulent time of constant war with his rival king Herod. This period applies to monetary upheaval. Mattathias' activities in the field of Numismatics has been significant and impressive. His minting Authority minted unique coins, while Herod also minted unique coins. Numismatic background before Mattathias Antigonus of the Hasmonean minting; The 3 Hasmonean kings prior to Mattathias Antigonus minted an abundance of unique coins. The first was John Hyrcanus I 135-104, who minted several series of coins, including a coin, possibly, together with Antiochus VII Sidetes minted in Jerusalem. On one side of the coin appears an inscription for Alexander Sidetes with the icon of the royal anchor. On the other side of the coin a model of the lily, the symbol of the Hasmonean priesthood. Another coin bearing the Greek letter alpha above a Paleo Hebrew legend "Yehohanan (John) the High priest and the Council of the Jews." The Alpha letter probably represents the first letter in the name of Antiochus VII Sidetes, and validates the Hebrew inscription underneath it. There are, however, researchers who believe otherwise. The other side of the coin bears the symbol of the cornucopia commonly shown on Hasmonean coins, including the pomegranate icon, which may symbolize the priesthood adopted by the Hasmonean dynasty. -

Sacrificial Cult at Qumran? an Evaluation of the Evidence in the Context of Other Alternate Jewish Practices in the Late Second Temple Period

SACRIFICIAL CULT AT QUMRAN? AN EVALUATION OF THE EVIDENCE IN THE CONTEXT OF OTHER ALTERNATE JEWISH PRACTICES IN THE LATE SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD Claudia E. Epley A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Classics Department in the College of Arts & Sciences. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Donald C. Haggis Jennifer E. Gates-Foster Hérica N. Valladares © 2020 Claudia E. Epley ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Claudia E. Epley: Sacrificial Cult at Qumran? An Evaluation of the Evidence in the Context of Other Alternate JeWish Practices in the Late Second Temple Period (Under the direction of Donald C. Haggis) This thesis reexamines the evidence for JeWish sacrificial cult at the site of Khirbet Qumran, the site of the Dead Sea Scrolls, in the first centuries BCE and CE. The interpretation of the animal remains discovered at the site during the excavations conducted by Roland de Vaux and subsequent projects has long been that these bones are refuse from the “pure” meals eaten by the sect, as documented in various documents among the Dead Sea Scrolls. However, recent scholarship has revisited the possibility that the sect residing at Qumran conducted their own animal sacrifices separate from the Jerusalem temple. This thesis argues for the likelihood of a sacrificial cult at Qumran as evidenced by the animal remains, comparable sacrificial practices throughout the Mediterranean, contemporary literary Works, and the existence of the JeWish temple at Leontopolis in lower Egypt that existed at the same time that the sect resided at Qumran.