2008 Bitterroot Mountains Bear DNA Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

6800-Year Vegetation and Fire History in the Bitterroot Mountain Range Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1995 6800-year vegetation and fire history in the Bitterroot Mountain Range Montana Anne Elizabeth Karsian The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Karsian, Anne Elizabeth, "6800-year vegetation and fire history in the Bitterroot Mountain Range Montana" (1995). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6683. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6683 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anne- K a r s j a n i Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY TheM University ontana of Permission is granted by tlie author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that tliis material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and repoits. * * Please check "Yes'' or “No “ and provide signature Yes, I grant permission ..\1 No, I do not grant permission ----- Author’s Signature Date; ' n 1 Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with ^he author’s explicit consent. ■ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A 6800-YEAR VEGETATION AND FIRE HISTORY IN THE BITTERROOT MOUNTAIN RANGE, MONTANA By ANNE ELIZABETH KARSIAN Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSHY OF MONTANA Department of Forestry 1995 Approved by: t' z o Chairperson 7 ^ ^ ^ /. -

Birding in the Missoula and Bitterroot Valleys

Birding in the Missoula and Bitterroot Valleys Five Valleys and Bitterroot Audubon Society Chapters are grassroots volunteer organizations of Montana Audubon and the National Audubon Society. We promote understanding, respect, and enjoyment of birds and the natural world through education, habitat protection, and environmental advocacy. Five Valleys Bitterroot Audubon Society Audubon Society P.O. Box 8425 P.O. Box 326 Missoula, MT 59807 Hamilton, MT 59840 www.fvaudubon.org/ www.bitterrootaudubonorg/ Montana Audubon P.O. Box 595 Helena, MT 59624 406-443-3949 www.mtaudubon.org Status W Sp Su F Bird Species of West-central Montana (most vagrants excluded) _ Harlequin Duck B r r r Relative abundance in suitable habitat by season are: _ Long-tailed Duck t r r c - common to abundant, usually found on every visit in _ Surf Scoter t r r r moderate to large numbers _ White-winged Scoter t r r r u - uncommon, usually present in low numbers but may be _ Common Goldeneye B c c c c _ missed Barrow’s Goldeneye B u c c c _ o - occasional, seen only a few times during the season, not Bufflehead B o c u c _ Hooded Merganser B o c c c present in all suitable habitat _ Common Merganser B c c c c r - rare, one to low numbers occur but not every year _ Red-breasted Merganser t o o _ Status: Ruddy Duck B c c c _ Osprey B c c c B - Direct evidence of breeding _ Bald Eagle B c c c c b - Indirect evidence of breeding _ Northern Harrier B u c c c t - No evidence of breeding _ Sharp-shinned Hawk B u u u u _ Cooper’s Hawk B u u u u Season of occurrence: _ Northern Goshawk B u u u u W - Winter, mid-November to mid-February _ Swainson’s Hawk B u u u Sp - Spring, mid-February to mid-May _ Red-tailed Hawk B c c c c Su - Summer, mid-May to mid-August _ Ferruginous Hawk t r r r F - Fall, mid-August to mid-November _ Rough-legged Hawk t c c c _ Golden Eagle B u u u u This list follows the seventh edition of the AOU check-list. -

Level IV Ecoregions of Montana

DRAFT 2 Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and ecosystem components. By recognizing the spatial differences in the capacities and potentials of ecosystems, ecoregions stratify the environment by its Ecoregions of Montana probable response to disturbance (Bryce and others, 1999). These general purpose regions are critical for Second Edition structuring and implementing ecosystem management strategies across federal agencies, state agencies, and nongovernment organizations that are responsible for different types of resources within the same 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° 108° 107° 106° 105° 104° geographical areas (Omernik and others, 2000). ° 49° The approach used to compile this map is based on the premise that ecological regions can be identified 49 BRITISH COLUMBIA 42d through the analysis of the spatial patterns and the composition of biotic and abiotic phenomena that affect ALBERTA SASKATCHEWAN 42k or reflect differences in ecosystem quality and integrity (Wiken, 1986; Omernik, 1987, 1995). These 15d CANADA 15h 41b 42q 42n sa 17r ATE S phenomena include geology, physiography, vegetation, climate, soils, land use, wildlife, and hydrology. u F 41a 42l UNITED ST n l Plentywood a a 42n 42r 42m Scobey c th 42r o e The relative importance of each characteristic varies from one ecological region to another regardless of o a 42r K d R e i 42r 17r the hierarchical level. A Roman numeral hierarchical scheme has been adopted for different levels of k v a 41c e r Fresno 15h L 42i 42b 42d ecological regions. -

Geological Survey

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BULLETIN OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 17O t, WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1900 UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SUKVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR SURVEY OF THE BOUNDARY LINE BETWEEN IDAHO AND MONTANA FROM THE INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARY TO THE CREST OF THE BITTERROOT MOUNTAINS BY RICHARD TJRQUHART GOODE WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1900 CONTENTS. Page. Letter of transmittal - _. .... _..._......_....--..,.. ........... 9 Instructions ...............................1...^.......................... 11 Boundary lines.-. ....--..........---.-.--..-.-..-............-.-.-..---- 15 Account of operations ...........................-._._........... .--. 18 Latitude, longitude, base line, azimuth, and triangulation _...__.._.._..___ 21 Latitude _...-. .--.---.-... -.....-..-..........._................ 21 Longitude.........---.-..-..-..-.....-..--.. ............. ....-.-. 23 Spokane base line................J......................__._._.. 25 Azimuth .__.---.--.-.-.....___.. _..--...__.__.__.. ._._........--. 25 Triangulation ................... __........._.'......._._._.....-- 29 Transit and stadia work.................................................. 40 Monuments _. ..;......____.._._.,_._._._....__,, ._.....__. ..-..... 47 The international boundary west of the summit of the Eocky Mountains, and the Mooyie Trail monument..............................._..... 58 Financial statement ................... °........................_.i........ 63 Index ..............J..................................................... -

Abandoned-Inactive Mines on Bitterroot National Forest-Administered Land

Abandoned-Inactive Mines on Bitterroot National Forest-Administered Land Map of the Curlew Mine by Rick Schmidt in MBMG mineral property files Open-File Report MBMG 484 Phyllis A. Hargrave Catherine McDonald Michael D. Kerschen John J. Metesh Robert Wintergerst Prepared for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service-Region 1 Abandoned-Inactive Mines on Bitterroot National Forest-Administered Land Open-File Report MBMG 484 October 2003 Phyllis A. Hargrave Catherine McDonald Michael D. Kerschen John J. Metesh Robert Wintergerst Prepared for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service-Region 1 CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................ iii 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................1 1.1 Project Objectives ....................................................1 1.2 Abandoned and Inactive Mines Defined . 2 1.3 Health and Environmental Problems at Mines . 2 1.3.1 Acid Mine Drainage ...........................................3 1.3.2 Solubilities of Selected Metals ...................................3 1.3.3 The Use of pH and SC to Identify Problems . 5 1.4 Methodology ........................................................5 1.4.1 Data Sources .................................................5 1.4.2 Pre-Field Screening............................................6 1.4.3 Field Screening ...............................................7 1.4.4 Field Methods ................................................8 -

Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Geologic Resources Division Denver, Colorado Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Report Glacier National Park Geologic Resource Evaluation Geologic Resources Division Denver, Colorado U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................. iv Executive Summary ...................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose of the Geologic Resource Evaluation Program ............................................................................................3 Geologic Setting .........................................................................................................................................................3 Glacial Setting ............................................................................................................................................................4 Geologic Issues............................................................................................................. 9 Economic Resources..................................................................................................................................................9 Mining Issues..............................................................................................................................................................9 -

Experience the Nez Perce Trail

Lolo, Montana, to the Big Hole National Battlefield, Montana, through the Bitterroot Valley Experience the Nez Perce Trail Bitterroot River © Jerry Bauer 1 The Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Designated by Congress in 1986, the entire Nez Perce National Historic Trail stretches 1,170 miles from the Wallowa Valley of eastern Oregon to the plains of north-central Montana. This segment of the Nez Perce National Historic Trail from Lolo, Montana, to the Big Hole Battlefield, Montana through the Bitterroot Valley is one of eight available tours (complete list on page 35). These are available at Forest Service offices and other federal and local visitor centers along the route. As you travel this historic trail, you will see highway signs marking the official Auto Tour route. Each Mainstream Auto Tour route stays on all-weather roads passable for all types of vehicles. Adventurous and Rugged Routes are an alternative for those seeking the most authentic historic route. They are often on gravel or dirt roads, so plan ahead. Check weather and road conditions before embarking on your journey. Call 511 for road condition reports on major routes. For road condition information on Adventurous and Rugged routes inquire locally. 3 Experience the Nez Perce Trail How do I get there? Mainstream Traveler (Passable for all types of vehicles.) This Auto Tour begins at Fort Fizzle, 4.6 miles west of Lolo Montana. Lolo is located approximately 7 miles south For most travelers this will be the appropriate route. of Missoula, Montana. The roads are generally paved and won’t pose a challenge for typical cars, campers with trailers, and RVs. -

Descriptions of the Level IV Ecoregions of Montana Second Edition

DRAFT 2 Descriptions of the Level IV Ecoregions of Montana Second Edition 15. Northern Rockies 17. Middle Rockies (continued) 18. Wyoming Basin 15a The Grave Creek Range-Nine Mile Divide ecoregion is composed of northwest- open, wind-blown stands of nonmarketable subalpine fir, Engelmann spruce, and whitebark pine The Bitterroot-Frenchtown Valley ecoregion is sheltered from high winds and severe The Rattlesnake-Blackfoot-South Swan-Northern Garnet-Sapphire Mountains The Bighorn Basin lies in the rainshadow of the Beartooth Plateau. It includes some of sedimentary rock and are often alkaline and/or gypsiferous. The potential natural vegetation is southeast trending, forested mountains that are partially mantled by volcanic ash and occur. Subalpine fir, whitebark pine, mountain hemlock, and alpine larch forests are found in 17s weather by surrounding mountains. It is composed of floodplains, terraces, hills, fans, 17x ecoregion is forested and lies west of the Continental Divide. Ecoregion 17x is underlain 18b the driest places in Montana, and parts receive an average of only six inches of mostly sagebrush steppe and is distinct from that of the surrounding ecoregions. Most land is underlain by Precambrian argillite, argillaceous rocks, and quartzite. It is more rugged than the glacial cirques. Elevations range from about 6,000 to just over 10,600 feet and are sufficient to wildlife-rich wetlands, and riparian forests. Thick alluvial and lacustrine deposits are common; primarily by a heterogeneous mixture of Precambrian Belt formations but Tertiary-Cretaceous precipitation per year. Unleached, nearly white soils commonly occur. These were derived from used for grazing but some irrigated agriculture occurs, especially near the Yellowstone River. -

Forests, Fuels and Fire in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, Idaho

Forests, Fuels and Fire in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, Idaho JAMES R. HABECK Department of Botany, University of Montana, Missoula INTRODUCTION THE Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness (SBW) is a 1.2 million-acre (486,000 ha) forested tract located in northern Idaho and portions of adjacent western Montana (46°00' N, 1150 W, Fig. 1). This wilderness represents the largest roadless area' in conterminous United States classified under the Wilderness Act of 1964. It lies within portions of the Nez Perce, Bitterroot, Clearwater and Lolo National Forests (Northern Region, USDA Forest Service) which collectively provide control and management for this wilder ness. Two of the current wilderness management objectives in the Sel way-Bitterroot Wilderness are (1) the determination of the natural role of wildfires within the varied forest communities composing the wilderness, and (2) the determination of suitable means of returning to wildfire at least some of these natural functions (Habeck and Mutch, 1973). The successful pursuit of these management ob jectives requires the development of a detailed description of forest compositions and distributions as well as an assessment of organic fuel production and accumulations within different forest types. Wildfire is believed to have played a critical ecological role as a decomposer of organic matter in many of the northern Rocky Moun tain coniferous forests (Habeck, 1972, 1973; Habeck and Mutch, 305 JAMES R. HABECK 1150 00' Vi,. 1 M"p of 'he p,,,Ii, Northwe" ,nil loc."on 01 >he Selw,,·Bi"""'" Wild"fie" in northern Idaho and adjacent ,,·estern Montana. 306 FORESTS. FUELS. FIRE IN WILDERNESS 1973), and consequently an integral and natural process in these ecosystems. -

Regional Overview -- Wildlife Subcommittee Report

1 Northern Regional Overview Wildlife Species: Status, Risk, Opportunities, and References Fred Samson Wildlife Ecologist Northern Region Ecosystems Ecosystem Status National Review In 1999, a group of scientists representing major conservation organization conducted a detailed review of the conservation status of each North American ecosystem in order to develop priorities to conserve biodiversity including wildlife species (Ricketts et al. 1999). Each major ecosystem was placed within the Ecological hierarchy developed by Bailey (1996), and is essential the same as the ecological hierarchy the Forest Service is encouraged to use in the Draft Directives that implement the 2005 Planning Rule. The review conducted Ricketts et al. (1999) placed each North American Ecoregion into one of five categories. Category Description I. Globally outstanding Ecoregion requiring immediate protection of remaining habitat and extensive restoration. II. Regionally outstanding Ecoregion requiring immediate protection of Remaining habitat and extensive restoration. III. Globally or regionally outstanding Ecoregion that present rare Opportunities to conserve large blocks of habitat. IV. Bioregionally and nationally important ecoregions requiring protection of Remaining habitat and extensive restoration. V. Bioregionally and national important ecoregions requiring protection or representative habitat blocks and proper management elsewhere for biodiversity conservation. In addition, each ecoregions was identified in terms of condition as Critical, Endangered, Vulnerable, 2 Relatively Stable, and Relatively Intact. Within the Northern Region, ecoregions were identified by Ricketts et al. (1999) to fall into the following categories. I. Globally Outstanding/Critical Tallgrass prairie (North Dakota) II Regionally Outstanding/Endangered Shortgrass prairie (South Dakota) IV Bioregionally outstanding/Endangered Snake/Columbia Shrub steppe (Idaho) IV Bioregionally outstanding/Vulnerable North Central and South Central Rocky Mountain Forests (Montana and Idaho) V. -

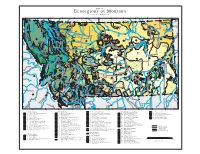

Ecoregions of Montana Second Edition

DRAFT 2 Ecoregions of Montana Second Edition 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° 108° 107° 106° 105° 104° 49° 49° BRITISH COLUMBIA 42d 42k ALBERTA CANADA SASKATCHEWAN 15d 41b 42q 42n 15h a s 17r NITED STATES u F 41a 42l U n l Plentywood a a 42n 42r 42m c t Scobey o h 42r e o a 42r K d R e i 42r 17r k v a 41c e r Fresno 15h L 42i 42b 42d K Reservoir o o Cut Bank N t e O n 41b 41b a S R i Rive a T r g Medicine 15t e Lake H Libby Shelby C Chinook D re Milk R 15q Havre ive A 42q ek r 42i Ma K r O 15l ias k R e i T ve e r A Lake r Malta 41a C Elwell y 15c d 15h n a 42j Kalispell S 42r g Glasgow i i uri R ver B o Conrad Wolf Point iss 43c 17r M ° 48° 15h 48 41d 43n e k 42r r 42r a 15l ive 43n L R 15o ri d 41b 42o ou 43c a ss e Teton River i 42r h 41e M t e 17r k a a l L Sidney F k Choteau ec 15k 15e 41b P 41c rt Fort Benton F o 15h Clar Polson 15o Thompson k F Mi or 43l ssour Falls k 15c 41d i River 42q r 43c e 15b iv R e 43l n Great Falls 42r to 17r s 15e i River w ur lo Fla o l thead Rive 41b s e r 41b is Jordan 43a Y 41b M M Superior 42q 43o 43n u s 15a s 15p e l 15a s 43n Glendive I h D 15c e A 43s l 15h l ° H R 47° 47 O i 43c 17r v 17r e 17x r 17p Lewistown Missoula 17aj 43s 43n 43a 43u 17t 43u 17al 17q 17q 16b 17x 17h 17w 43c 17al Helena White 17ak C Sulphur la 43e 43b rk 17v r Springs 43m e 17s 17x F v o i r Canyon Miles 43c R k t 17aj Ferry City 16e o 17q Harlowton Baker o 17h r Lake 43p r Roundup e t t 17ak Deer i ne River B wsto Lodge Yello Townsend 43p Hamilton 17am Musselshell River Forsyth 43t 17f Anaconda Boulder 17y 43p 43p