Experience the Nez Perce Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photo Guide for Appraising Downed Woody Fuels in Montana Forests

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. USDA FOREST SERVICE GENERAL TECHNICAL REPORT INT-96 NOVEMBER 1981 PHOTO GUIDE FOR APPRAISING DOWNED WOODY FUELS IN MONTANA FORESTS: Grand Fir- Larch-Douglas-Fir, Western Hemlock, Western Hemlock-Western Redcedar, and Western Redcedar Cover Types William C. Fischer INTERMOUNTAIN FOREST AND RANGE EXPERIMENT STATION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE OGDEN, UTAH 84401 THE AUTHOR WILLIAM C. FISCHER is a research forester for the Fire Effects and Use Research and Development Program, at the Northern Forest Fire Laboratory. His current assignment is to develop techniques and procedures for applying existing research knowledge to the task of producing improved operational fire management plans, with special emphasis on fire use, fuel treatment, and fuel management plans. Mr. Fischer received his bachelor's degree in forestry from the University of Michigan in 1956. From 1956 to 1966, he did Ranger District and forest staff work in timber management and fire control on the Boise National Forest. RESEARCH SUMMARY Four series of color photographs show different levels of ,downed woody material resulting from natural processes in four forest cover types in Montana. Each photo is supplemented by inventory data describing the size, weight, volume, and condition of the debris pictured. A subjective evaluation of potential fire behavior under an average bad fire weather situation is given. I nstructions are provided for using the photos to describe fuels and to evaluate potential fire hazard. USDA FOREST SERVICE GENERAL TECHNICAL REPORT INT-96 NOVEM,BER 1981 PHOTO GUIDE FOR APPRAISING DOWNED WOODY FUELS IN MONTANA FORESTS: Grand Fir- Larch-Douglas-Fir, Western Hemlock, We~tern Hemlock-Western Redcedar, and Western Redcedar Cover Types Will iam C. -

Big Hole River Fluvial Arctic Grayling

FLUVIAL ARCTIC GRAYLING MONITORING REPORT 2003 James Magee and Peter Lamothe Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks Dillon, Montana Submitted To: Fluvial Arctic Grayling Workgroup And Beaverhead National Forest Bureau of Land Management Montana Chapter, American Fisheries Society Montana Council, Trout Unlimited Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service June 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The following individuals and organizations contributed valuable assistance to the project in 2003. Scott Lula, Greg Gibbons, Zachary Byram, Tracy Elam, Tim Mosolf, and Dick Oswald of Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks (FWP), provided able field assistance. Ken Staigmiller (FWP) collected samples for disease testing. Ken McDonald (FWP), provided administrative support, chaired the Fluvial Arctic Grayling Workgroup, reviewed progress reports and assisted funding efforts. Bob Snyder provided support as Native Species Coordinator. Dick Oswald (FWP) provided technical advice and expertise. Bruce Rich (FWP) provided direction as regional fisheries supervisor. Jim Brammer, Dennis Havig, Dan Downing, and Chris Riley (USFS) assisted with funding, provided housing for FWP technicians, and assisted with fieldwork. Bill Krise, and Ron Zitzow, Matt Toner, and the staff of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Bozeman Fish Technology Center maintained the brood reserve stock and transported grayling to the upper Ruby River. Jack Boyce, Mark Kornick and Jim Drissell, and crew of Big Springs Hatchery assisted with egg takes at Axolotl and Green Hollow II brood lakes, and transported eyed grayling eggs for RSI use in the upper Ruby River and to Bluewater State Fish Hatchery for rearing reaches. Gary Shaver, Bob Braund, and Dave Ellis from Bluewater State Hatchery raised and transported grayling to the Ruby River and the Missouri Headwaters restoration reaches. -

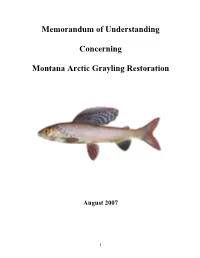

Memorandum of Understanding Concerning Montana Arctic

Memorandum of Understanding Concerning Montana Arctic Grayling Restoration August 2007 1 MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING among: MONTANA FISH, WILDLIFE & PARKS (FWP) U.S. BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT (BLM) U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE (USFWS) U.S. FOREST SERVICE (USFS) MONTANA COUNCIL TROUT UNLIMITED (TU) MONTANA CHAPTER AMERICAN FISHERIES SOCIETY (AFS) YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK (YNP) MONTANA ARCTIC GRAYLING RECOVERY PROGRAM (AGRP) USDA NATURAL RESOURCE CONSERVATION SERVICE (NRCS) MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES AND CONSERVATION (DNRC) concerning MONTANA ARCTIC GRAYLING RESTORATION BACKGROUND Montana’s Arctic grayling Thymallus arcticus is a unique native species that comprises an important component of Montana’s history and natural heritage. Fluvial (river dwelling) Arctic grayling were once widespread in the Missouri River drainage, but currently wild grayling persist only in the Big Hole River, representing approximately 4% of their native range in Montana. Native lacustrine/adfluvial populations historically distributed in the Red Rock drainage and possibly the Big Hole drainage have also been reduced in abundance and distribution. Arctic grayling have a long history of being petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Most recently (in April 2007) the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) determined that listing of Arctic grayling in Montana under ESA was not warranted because it does not constitute a distinct population segment as defined by the ESA. On May 15th 2007, the Center for Biological Diversity announced its 60-day Intent to Sue the USFWS regarding the recent grayling decision. The Montana Arctic Grayling Recovery Program (AGRP) was formed in 1987 following declines in the Big Hole River Arctic grayling population, and over concerns for the Red Rock population. -

IMBCR Report

Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR): 2015 Field Season Report June 2016 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies 14500 Lark Bunting Lane Brighton, CO 80603 303-659-4348 www.birdconservancy.org Tech. Report # SC-IMBCR-06 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies Connecting people, birds and land Mission: Conserving birds and their habitats through science, education and land stewardship Vision: Native bird populations are sustained in healthy ecosystems Bird Conservancy of the Rockies conserves birds and their habitats through an integrated approach of science, education and land stewardship. Our work radiates from the Rockies to the Great Plains, Mexico and beyond. Our mission is advanced through sound science, achieved through empowering people, realized through stewardship and sustained through partnerships. Together, we are improving native bird populations, the land and the lives of people. Core Values: 1. Science provides the foundation for effective bird conservation. 2. Education is critical to the success of bird conservation. 3. Stewardship of birds and their habitats is a shared responsibility. Goals: 1. Guide conservation action where it is needed most by conducting scientifically rigorous monitoring and research on birds and their habitats within the context of their full annual cycle. 2. Inspire conservation action in people by developing relationships through community outreach and science-based, experiential education programs. 3. Contribute to bird population viability and help sustain working lands by partnering with landowners and managers to enhance wildlife habitat. 4. Promote conservation and inform land management decisions by disseminating scientific knowledge and developing tools and recommendations. Suggested Citation: White, C. M., M. F. McLaren, N. J. -

Ruby River Access Sites Secured by Bruce Farling Hen the Topic of Stream Access Families, There Would Be No Formal Fishing Ago

SPRING TROUT LINE 2016 Newsletter from the Montana Council of Trout Unlimited Ruby River access sites secured by Bruce Farling hen the topic of stream access families, there would be no formal fishing ago. Because of budget constraints, and the Ruby River is raised access sites for 40-plus river miles below some caused by limits imposed by Win Montana it’s often related the Vigilante Fishing Access Site a couple the Legislature, as well as demands at to absentee landowner James Cox miles downstream of the Ruby River Dam. some of the other 330 sites in FWP’s Kennedy from Atlanta and his 15-year Three county bridge popular fishing access legal and political efforts to prevent the rights-of-way provide site program, the public from accessing this great fishery. the only other points department didn’t However, not all stories about stream of access on the lower have adequate funding access coming from the Ruby Valley river. But the bridges to renew the leases for are as distressing as the Kennedy tale. have limited parking. the previous agreed Recently we can thank some civic-minded Plus, Mr. Kennedy upon price. The ranchers and, in part, Montana TU and has contested bridge Doornbos, Barnosky three of its chapters for a bit of good access in court and and Guillame families, news about the Ruby. made getting to the however, graciously Since the mid-1990s, three long- river at those spots agreed to lease the time ranching families in the valley have physically difficult access sites at a much- been leasing portions of their properties with his fencing schemes. -

Through the Bitterroot Valley -1877

Th^ Flight of the NezFexce ...through the Bitterroot Valley -1877 United States Forest Bitterroot Department of Service National Agriculture Forest 1877 Flight of the Nez Perce ...through the Bitterroot Valley July 24 - Two companies of the 7th Infantry with Captain Rawn, sup ported by over 150 citizen volunteers, construct log barricade across Lolo Creek (Fort Fizzle). Many Bitterroot Valley women and children were sent to Fort Owen, MT, or the two hastily constructed forts near Corvallis and Skalkaho (Grantsdale). July 28 - Nez Perce by-pass Fort Fizzle, camp on McClain Ranch north of Carlton Creek. July 29 - Nez Perce camp near Silverthorn Creek, west of Stevensville, MT. July 30 - Nez Perce trade in Stevensville. August 1 - Nez Perce at Corvallis, MT. August 3 - Colonel Gibbon and 7th Infantry reach Fort Missoula. August 4 - Nez Perce camp near junction of East and West Forks of the Bitterroot River. Gibbon camp north of Pine Hollow, southwest of Stevensville. August 5 - Nez Perce camp above Ross' Hole (near Indian Trees Camp ground). Gibbon at Sleeping Child Creek. Catlin and volunteers agree to join him. August 6 - Nez Perce camp on Trail Creek. Gibbon makes "dry camp" south of Rye Creek on way up the hills leading to Ross' Hole. General Howard at Lolo Hot Springs. August 7 - Nez Perce camp along Big Hole River. Gibbon at foot of Conti nental Divide. Lieutenant Bradley sent ahead with volunteers to scout. Howard 22 miles east of Lolo Hot Springs. August 8 - Nez Perce in camp at Big Hole. Gibbon crosses crest of Continen tal Divide parks wagons and deploys his command, just a few miles from the Nez Perce camp. -

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2015

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2015 Administrator’s Corner Greetings, Trail Fit? Are you up for the challenge? A trail hike or run can provide unique health results that cannot be achieved indoors on a treadmill while staring at a wall or television screen. Many people know instinctively that a walk on a trail in the woods will also clear the mind. There is a new generation that is already part of the fitness movement and eager for outdoor adventure of hiking, cycling, and horseback riding-yes horseback riding is exercise not only for the horse, but also the rider. We are encouraging people to get out on the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Photo Service Forest U.S. (NPNHT) and Auto Tour Route to enjoy the many health Sandra Broncheau-McFarland benefits it has to offer. Remember to hydrate during these hot summer months. The NPNHT and Auto Tour Route is ripe for exploration! There are many captivating places and enthralling landscapes. Taking either journey - the whole route or sections, one will find unique and authentic places like nowhere else. Wherever one goes along the Trail or Auto Tour Route, they will encounter moments that will be forever etched in their memory. It is a journey of discovery. The Trail not only provides alternative routes to destinations throughout the trail corridor, they are destinations in themselves, each with a unique personality. This is one way that we can connect people to place across time. We hope you explore the trail system as it provides opportunities for bicycling, walking, hiking, running, skiing, horseback riding, kayaking, canoeing, and other activities. -

6800-Year Vegetation and Fire History in the Bitterroot Mountain Range Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1995 6800-year vegetation and fire history in the Bitterroot Mountain Range Montana Anne Elizabeth Karsian The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Karsian, Anne Elizabeth, "6800-year vegetation and fire history in the Bitterroot Mountain Range Montana" (1995). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6683. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6683 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anne- K a r s j a n i Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY TheM University ontana of Permission is granted by tlie author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that tliis material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and repoits. * * Please check "Yes'' or “No “ and provide signature Yes, I grant permission ..\1 No, I do not grant permission ----- Author’s Signature Date; ' n 1 Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with ^he author’s explicit consent. ■ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A 6800-YEAR VEGETATION AND FIRE HISTORY IN THE BITTERROOT MOUNTAIN RANGE, MONTANA By ANNE ELIZABETH KARSIAN Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSHY OF MONTANA Department of Forestry 1995 Approved by: t' z o Chairperson 7 ^ ^ ^ /. -

Birding in the Missoula and Bitterroot Valleys

Birding in the Missoula and Bitterroot Valleys Five Valleys and Bitterroot Audubon Society Chapters are grassroots volunteer organizations of Montana Audubon and the National Audubon Society. We promote understanding, respect, and enjoyment of birds and the natural world through education, habitat protection, and environmental advocacy. Five Valleys Bitterroot Audubon Society Audubon Society P.O. Box 8425 P.O. Box 326 Missoula, MT 59807 Hamilton, MT 59840 www.fvaudubon.org/ www.bitterrootaudubonorg/ Montana Audubon P.O. Box 595 Helena, MT 59624 406-443-3949 www.mtaudubon.org Status W Sp Su F Bird Species of West-central Montana (most vagrants excluded) _ Harlequin Duck B r r r Relative abundance in suitable habitat by season are: _ Long-tailed Duck t r r c - common to abundant, usually found on every visit in _ Surf Scoter t r r r moderate to large numbers _ White-winged Scoter t r r r u - uncommon, usually present in low numbers but may be _ Common Goldeneye B c c c c _ missed Barrow’s Goldeneye B u c c c _ o - occasional, seen only a few times during the season, not Bufflehead B o c u c _ Hooded Merganser B o c c c present in all suitable habitat _ Common Merganser B c c c c r - rare, one to low numbers occur but not every year _ Red-breasted Merganser t o o _ Status: Ruddy Duck B c c c _ Osprey B c c c B - Direct evidence of breeding _ Bald Eagle B c c c c b - Indirect evidence of breeding _ Northern Harrier B u c c c t - No evidence of breeding _ Sharp-shinned Hawk B u u u u _ Cooper’s Hawk B u u u u Season of occurrence: _ Northern Goshawk B u u u u W - Winter, mid-November to mid-February _ Swainson’s Hawk B u u u Sp - Spring, mid-February to mid-May _ Red-tailed Hawk B c c c c Su - Summer, mid-May to mid-August _ Ferruginous Hawk t r r r F - Fall, mid-August to mid-November _ Rough-legged Hawk t c c c _ Golden Eagle B u u u u This list follows the seventh edition of the AOU check-list. -

BIG HOLE National Battlefield

BIG HOLE National Battlefield Historical Research Management Plan & Bibliography of the ERCE WAR, 1877 F 737 .B48H35 November 1967 Historical Research Management Plan BIG HOLE NATI ONAL for .BATILEFIELD LI BRP..RY BIG HOLE Na tional Battlefield & Bibliog raphy of the N E Z PERCE WAR, 1877 By AUBREY L. HAINES DIVISION OF HISTORY Office of Archeology and Historic Preservatio.n November 1967 U.S. Department of the Interior NATI ONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL RESEARCH MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR BIG HOLE NATIONAL BATTLEFIELD November 1968 Recommended Superintendent Date Reviewed Division of History Date Approved Chief, Office of Archeology Date and Historic Preservation i TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Research Management Plan Approval Sheet I. The Park Story and Purpose . • • • 1 A. The Main His torical Theme ••••••• 1 B. Sub sidiary Historical Theme • • • • • 1 1 c. Relationship of Historical Themes to Natural History and Anthropology • • • • • • • • 12 D. Statement of Historical Significance •• 14 E. Reasons for Establishment of the Park • • • • • 15 II. Historical Resources of the Battlefield 1 7 A. Tangible Resources • • • • 17 1. Sites and Remains 1 7 a. Those Related to the Main Park Theme • • . 1 7 b. Those Related to Subsidiary Themes • 25 2. Historic Structures 27 B. Intangible Resources • 2 7 c. Other Resources 2 8 III.Status of Research •• 2 9 A. Research Accomplished 29 H. Research in Progress • • • • • 3o c. Cooperation with Non-Service Institutions 36 IV. Research Needs ••••••••••••••••• 37 A. Site Identification and Evaluation Studies 37 H. General Background Studies and Survey Histories 40 c. Studies for Interpretive Development • • • • • 4 1 D. Development Studies • • • • • • • • • 4 1 E. -

Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report

United States Department of Agriculture Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail Progress Report Summer 2019 Administrator ’s Corner At the Nez Perce (Nee-Me-Poo) National Historic Trail (NPNHT) program, we work through partnerships that seek to create communication and collaboration across jurisdictional and cultural boundaries. Our ethic of working together reinforces community bonds, strengthens our Trail social fabric, and fosters community prosperity. By building stronger relationships and reaching out to underserved communities, who may have not historically had a voice in the management, interpretation of the Trail, we can more effectively steward our trail through honoring all the communities we serve. U.S. Forest Service photo, U.S. Roger Peterson Forest Service Volunteer labor isn’t perfect sometimes. Construction projects can take Sandra Broncheau-McFarland, speaking to longer than necessary, but there are so many intangible benefits of the Chief Joseph Trail Riders. volunteering- the friendships, the cross-cultural learning, and the life changes it inspires in volunteers who hopefully shift how they live, travel, and give in the future. Learning how to serve and teaching others the rest of our lives by how we live is the biggest impact. Volunteering is simply the act of giving your time for free and so much more. In an always on and interconnected world, one of the hardest things to find is a place to unwind. Our brains and our bodies would like us to take things a lot slower,” says Victoria Ward, author of “The Bucket List: Places to find Peace and Quiet.” This is the perfect time to stop and appreciate the amazing things happening around you.