Paratachardina Pseudolobata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invasive Insects (Adventive Pest Insects) in Florida1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. ENY-827 Invasive Insects (Adventive Pest Insects) in Florida1 J. H. Frank and M. C. Thomas2 What is an Invasive Insect? include some of the more obscure native species, which still are unrecorded; they do not include some The term 'invasive species' is defined as of the adventive species that have not yet been 'non-native species which threaten ecosystems, detected and/or identified; and they do not specify the habitats, or species' by the European Environment origin (native or adventive) of many species. Agency (2004). It is widely used by the news media and it has become a bureaucratese expression. This is How to Recognize a Pest the definition we accept here, except that for several reasons we prefer the word adventive (meaning they A value judgment must be made: among all arrived) to non-native. So, 'invasive insects' in adventive species in a defined area (Florida, for Florida are by definition a subset (those that are example), which ones are pests? We can classify the pests) of the species that have arrived from abroad more prominent examples, but cannot easily decide (adventive species = non-native species = whether the vast bulk of them are 'invasive' (= pests) nonindigenous species). We need to know which or not, for lack of evidence. To classify them all into insect species are adventive and, of those, which are pests and non-pests we must draw a line somewhere pests. in a continuum ranging from important pests through those that are uncommon and feed on nothing of How to Know That a Species is consequence to humans, to those that are beneficial. -

Calophyllum Brasiliense Extracts Induced Apoptosis in Human Breast Adenocarcinoma Cells

European Journal of Medicinal Plants 32(4): 50-64, 2021; Article no.EJMP.69623 ISSN: 2231-0894, NLM ID: 101583475 Calophyllum brasiliense Extracts Induced Apoptosis in Human Breast Adenocarcinoma Cells Michelle S. F. Correia1, Anuska M. Alvares-Saraiva1, Elizabeth C. P. Hurtado1, Mateus L. B. Paciencia2, Fabiana T. C. Konno1, Sergio A. Frana1,2 and Ivana B. Suffredini1,2* 1Program in Environmental and Experimental Pathology, Paulista University, R. Dr. Bacelar, 1212, São Paulo, SP, 04026-002, Brazil. 2Center for Research in Biodiversity, Paulista University, Av. Paulista, 900, 1 Andar, São Paulo, SP, 01310-100, Brazil. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Authors IBS, AMAS, ECPH, FTCK’ designed the study, author IBS performed the statistical analysis and wrote the protocol, authors MSFC and IBS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors MSFC, SAF and MLBP managed the analyses of the study and the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/EJMP/2021/v32i430384 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Francisco Cruz-Sosa, Metropolitan Autonomous University, México. (2) Prof. Marcello Iriti, Milan State University, Italy. Reviewers: (1) Zeuko’o Menkem Elisabeth, University of Buea, Cameroon. (2) Ravi Prem Kalsait, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Technological University, India. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/69623 Received 10 April 2021 Accepted 15 June 2021 Original Research Article Published 21 June 2021 ABSTRACT Aims: Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is linked to several mechanisms of cell growth control. The present work aimed at evaluating the induction of apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma cell by Calophyllum brasiliense. -

Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve

Some Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve Some by Aniruddha Dhamorikar Insects & Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve Aniruddha Dhamorikar 1 2 Study of some Insect orders (Insecta) and Spiders (Arachnida: Araneae) of Kanha Tiger Reserve by The Corbett Foundation Project investigator Aniruddha Dhamorikar Expert advisors Kedar Gore Dr Amol Patwardhan Dr Ashish Tiple Declaration This report is submitted in the fulfillment of the project initiated by The Corbett Foundation under the permission received from the PCCF (Wildlife), Madhya Pradesh, Bhopal, communication code क्रम 車क/ तकनीकी-I / 386 dated January 20, 2014. Kanha Office Admin office Village Baherakhar, P.O. Nikkum 81-88, Atlanta, 8th Floor, 209, Dist Balaghat, Nariman Point, Mumbai, Madhya Pradesh 481116 Maharashtra 400021 Tel.: +91 7636290300 Tel.: +91 22 614666400 [email protected] www.corbettfoundation.org 3 Some Insects and Spiders of Kanha Tiger Reserve by Aniruddha Dhamorikar © The Corbett Foundation. 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used, reproduced, or transmitted in any form (electronic and in print) for commercial purposes. This book is meant for educational purposes only, and can be reproduced or transmitted electronically or in print with due credit to the author and the publisher. All images are © Aniruddha Dhamorikar unless otherwise mentioned. Image credits (used under Creative Commons): Amol Patwardhan: Mottled emigrant (plate 1.l) Dinesh Valke: Whirligig beetle (plate 10.h) Jeffrey W. Lotz: Kerria lacca (plate 14.o) Piotr Naskrecki, Bud bug (plate 17.e) Beatriz Moisset: Sweat bee (plate 26.h) Lindsay Condon: Mole cricket (plate 28.l) Ashish Tiple: Common hooktail (plate 29.d) Ashish Tiple: Common clubtail (plate 29.e) Aleksandr: Lacewing larva (plate 34.c) Jeff Holman: Flea (plate 35.j) Kosta Mumcuoglu: Louse (plate 35.m) Erturac: Flea (plate 35.n) Cover: Amyciaea forticeps preying on Oecophylla smargdina, with a kleptoparasitic Phorid fly sharing in the meal. -

Complete Inventory

Maya Ethnobotany Complete Inventory of plants 1 Fifth edition, November 2011 Maya Ethnobotany Complete Inventory:: fruits,nuts, root crops, grains,construction materials, utilitarian uses, sacred plants, sacred flowers Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, Honduras Nicholas M. Hellmuth Maya Ethnobotany Complete Inventory of plants 2 Introduction This opus is a progress report on over thirty years of studying plants and agriculture of the present-day Maya with the goal of understanding plant usage by the Classic Maya. As a progress report it still has a long way to go before being finished. But even in its unfinished state, this report provides abundant listings of plants in a useful thematic arrangement. The only other publication that I am familiar with which lists even close to most of the plants utilized by the Maya is in an article by Cyrus Lundell (1938). • Obviously books on Mayan agriculture should have informative lists of all Maya agricultural crops, but these do not tend to include plants used for house construction. • There are monumental monographs, such as all the trees of Guatemala (Parker 2008) but they are botanical works, not ethnobotanical, and there is no cross-reference by kind of use. You have to go through over one thousand pages and several thousand tree species to find what you are looking for. • There are even important monographs on Maya ethnobotany, but they are usually limited to one country, or one theme, often medicinal plants. • There are even nice monographs on edible plants of Central America (Chízmar 2009), but these do not include every local edible plant, and their focus is not utilitarian plants at all, nor sacred plants. -

Microscopic, Histochemical and Preliminary Phytochemical Characterization of Leaves of Trema Micrantha (L.) Blume

Anales de Biología 43: 93-99, 2021 ARTICLE http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesbio.43.09 ISSN/eISSN 1138-3399/1989-2128 Microscopic, histochemical and preliminary phytochemical characterization of leaves of Trema micrantha (L.) Blume Cledson dos Santos Magalhães1, Rafaela Damasceno Sá1, Solma Lúcia Souto Maior de Araújo Baltar2 & Karina Perrelli Randau1 1 Departamento de Ciências Farmacêuticas, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, 50740-321, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. 2 Universidade Federal de Alagoas, 57309-005, Arapiraca, Alagoas, Brazil. Resumen Correspondence Caracterización microscópica, histoquímica y fitoquímica preilmi- K.P. Randau nar de las hojas de Trema micrantha (L.) Blume E-mail: [email protected] Para enriquecer el enriquecer el conocimiento sobre Trema mi- Received: 22 November 2020 crantha (L.) Blume, esta investigación tuvo como objetivo realizar Accepted: 15 April 2021 la caracterización anatómica, histoquímica y fitoquímica de las ho- Published on-line: 30 May 2021 jas de la especie. Se realizaron cortes transversales del pecíolo y limbo, así como cortes paradérmicos del limbo, analizados en mi- croscopía óptica y polarizada. Se utilizaron diferentes reactivos para el análisis histoquímico. Se han descrito estructuras anatómi- cas que proporcionan un diagnóstico detallado de las especies es- tudiadas. La histoquímica mostró la presencia de metabolitos es- enciales (flavonoides, taninos, entre otros) para la especie y me- diante análisis SEM-EDS se confirmó que los cristales están com- puestos por oxalato de calcio. El análisis fitoquímico permitió la identificación de mono y sesquiterpenos, triterpenos y esteroides, entre otros. El estudio proporcionó datos sin precedentes sobre la especie, ampliando la información científica de T. micrantha. Palabras clave: Cannabaceae; Microscopía; Farmacobotánica. -

Leafing Through History

Leafing Through History Leafing Through History Several divisions of the Missouri Botanical Garden shared their expertise and collections for this exhibition: the William L. Brown Center, the Herbarium, the EarthWays Center, Horticulture and the William T. Kemper Center for Home Gardening, Education and Tower Grove House, and the Peter H. Raven Library. Grateful thanks to Nancy and Kenneth Kranzberg for their support of the exhibition and this publication. Special acknowledgments to lenders and collaborators James Lucas, Michael Powell, Megan Singleton, Mimi Phelan of Midland Paper, Packaging + Supplies, Dr. Shirley Graham, Greg Johnson of Johnson Paper, and the Campbell House Museum for their contributions to the exhibition. Many thanks to the artists who have shared their work with the exhibition. Especial thanks to Virginia Harold for the photography and Studiopowell for the design of this publication. This publication was printed by Advertisers Printing, one of only 50 U.S. printing companies to have earned SGP (Sustainability Green Partner) Certification, the industry standard for sustainability performance. Copyright © 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden 2 James Lucas Michael Powell Megan Singleton with Beth Johnson Shuki Kato Robert Lang Cekouat Léon Catherine Liu Isabella Myers Shoko Nakamura Nguyen Quyet Tien Jon Tucker Rob Snyder Curated by Nezka Pfeifer Museum Curator Stephen and Peter Sachs Museum Missouri Botanical Garden Inside Cover: Acapulco Gold rolling papers Hemp paper 1972 Collection of the William L. Brown Center [WLBC00199] Previous Page: Bactrian Camel James Lucas 2017 Courtesy of the artist Evans Gallery Installation view 4 Plants comprise 90% of what we use or make on a daily basis, and yet, we overlook them or take them for granted regularly. -

Phenology of Ficus Variegata in a Seasonal Wet Tropical Forest At

Joumalof Biogeography (I1996) 23, 467-475 Phenologyof Ficusvariegata in a seasonalwet tropicalforest at Cape Tribulation,Australia HUGH SPENCER', GEORGE WEIBLENI 2* AND BRIGITTA FLICK' 'Cape TribulationResearch Station, Private Mail Bag5, Cape Tribulationvia Mossman,Queensland 4873, Australiaand 2 The Harvard UniversityHerbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue,Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA Abstract. We studiedthe phenologyof 198 maturetrees dioecious species, female and male trees initiatedtheir of the dioecious figFicus variegataBlume (Moraceae) in a maximalfig crops at differenttimes and floweringwas to seasonally wet tropical rain forestat Cape Tribulation, some extentsynchronized within sexes. Fig productionin Australia, from March 1988 to February 1993. Leaf the female (seed-producing)trees was typicallyconfined productionwas highlyseasonal and correlatedwith rainfall. to the wet season. Male (wasp-producing)trees were less Treeswere annually deciduous, with a pronouncedleaf drop synchronizedthan femaletrees but reacheda peak level of and a pulse of new growthduring the August-September figproduction in the monthsprior to the onset of female drought. At the population level, figs were produced figproduction. Male treeswere also morelikely to produce continuallythroughout the study but there were pronounced figscontinually. Asynchrony among male figcrops during annual cyclesin figabundance. Figs were least abundant the dry season could maintainthe pollinatorpopulation duringthe early dry period (June-September)and most under adverseconditions -

Coccidology. the Study of Scale Insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria (E-Journal) Revista Corpoica – Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria (2008) 9(2), 55-61 RevIEW ARTICLE Coccidology. The study of scale insects (Hemiptera: Takumasa Kondo1, Penny J. Gullan2, Douglas J. Williams3 Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea) Coccidología. El estudio de insectos ABSTRACT escama (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: A brief introduction to the science of coccidology, and a synopsis of the history, Coccoidea) advances and challenges in this field of study are discussed. The changes in coccidology since the publication of the Systema Naturae by Carolus Linnaeus 250 years ago are RESUMEN Se presenta una breve introducción a la briefly reviewed. The economic importance, the phylogenetic relationships and the ciencia de la coccidología y se discute una application of DNA barcoding to scale insect identification are also considered in the sinopsis de la historia, avances y desafíos de discussion section. este campo de estudio. Se hace una breve revisión de los cambios de la coccidología Keywords: Scale, insects, coccidae, DNA, history. desde la publicación de Systema Naturae por Carolus Linnaeus hace 250 años. También se discuten la importancia económica, las INTRODUCTION Sternorrhyncha (Gullan & Martin, 2003). relaciones filogenéticas y la aplicación de These insects are usually less than 5 mm códigos de barras del ADN en la identificación occidology is the branch of in length. Their taxonomy is based mainly de insectos escama. C entomology that deals with the study of on the microscopic cuticular features of hemipterous insects of the superfamily Palabras clave: insectos, escama, coccidae, the adult female. -

Tree Management Plan DRAFT Otter Mound Preserve, Marco Island, FL

Tree Management Plan DRAFT Otter Mound Preserve, Marco Island, FL Prepared by: Alexandra Sulecki, Certified Arborist FL0561A February 2013 INTRODUCTION The Otter Mound Preserve is a 2.45-acre urban preserve located at 1831 Addison Court within the boundaries of the City of Marco Island in southwestern Collier County, Florida. The preserve lies within the “Indian Hills” section, on the south side of the island. Three parcels totaling 1.77 acres were acquired by Collier County under the Conservation Collier Program in 2004. An additional adjoining .68 acre parcel was acquired in 2007. The property was purchased primarily to protect the existing native Tropical Hardwood Hammock vegetation community. Tropical Hardwood Hammock is becoming rare in Collier County because its aesthetic qualities and location at higher elevations along the coast make it attractive for residential development. Tropical Hardwood Hammock is identified as a priority vegetation community for preservation under the Conservation Collier Ordinance, (Ord. 2002- 63, as amended, Section 10 1.A). The Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI) associates Tropical Hardwood Hammock with a natural community identified as “Shell Mound,” which is imperiled statewide (ranking of S2) and globally (ranking of G2), due to its rarity (Guide to the Natural Communities of Florida, 2010). The preserve is managed for conservation, restoration and passive public use. The Preserve’s forest has conservation features that draw visitors. Its canopy serves as an important stopover site for a variety of migratory bird species and is home to the Florida tree snail (Liguus fasciatus), a Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) Species of Special Concern. -

Survey of Mangosteen Clones with Distinctive Morphology in Eastern of Thailand

International Journal of Agricultural Technology 2015 Vol.Fungal 11(2): Diversity 227-242 Available online http://www.ijat-aatsea.com ISSN 2630-0192 (Online) Survey of Mangosteen Clones with Distinctive Morphology in Eastern of Thailand Makhonpas, C*., Phongsamran, S. and Silasai, A. School of Crop Production Technology and Landscape, Faculty of Agro-Industial Technology, Rajamangala University of Technology, Chanthaburi Campus, Thailand. Makhonpas, C., Phongsamran, S. and Silasai, A. (2015). Survey of mangosteen clones with distinctive morphology in eastern of Thailand. International Journal of Agricultural Technology Vol. 11(2):227-242. Abstract Mangosteen clone survey in Eastern Region of Thailand as Rayong, Chanthaburi and Trat Province in 2008 and 2009 showed diferential morphology as mangosteen phenotype was different and could be distinguished in 6 characters i.e small leave and small fruits trees, oblong shape trees, thin (not prominent) persistent stigma lobe thickness fruit trees, full and partial variegated mature leave color (combination of green and white color) trees, oblong shape leave trees and greenish yellow mature fruit color trees. Generally, rather short shoot, elliptic leaf blade shape, undulate leaf blade margin and thin or cavitied persistent stigma lobe thickness fruits are dominant marker of full seedless fruits that rarely found trees. Survey of mid-sized mangosteen orchards (200-300 trees) showed that over 70% full seedless fruits trees could be found only about 1-3% of all trees. Keywords: clones, mangosteen, phenotypes Introduction Mangosteen is a tropical fruit that grows and bears good fruit in Thailand. The fruit is delicious. It is popular with consumers both in Thailand and abroad, and has been called the queen of tropical fruits. -

Brya Ebenus (L.) DC

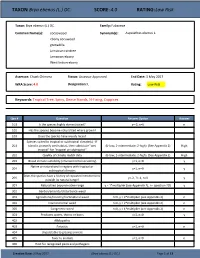

TAXON: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. SCORE: 4.0 RATING: Low Risk Taxon: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. Family: Fabaceae Common Name(s): cocoswood Synonym(s): Aspalathus ebenus L. ebony cocuwood grenadilla Jamaican raintree Jamaican-ebony West Indian-ebony Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 3 May 2017 WRA Score: 4.0 Designation: L Rating: Low Risk Keywords: Tropical Tree, Spiny, Dense Stands, N-Fixing, Coppices Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 y 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens Creation Date: 3 May 2017 (Brya ebenus (L.) DC.) Page 1 of 13 TAXON: Brya ebenus (L.) DC. -

SPECIAL SECTION Phenology of Ficus Racemosa in Xishuangbanna

SPECIAL SECTION BIOTROPICA 38(3): 334–341 2006 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2006.00150.x Phenology of Ficus racemosa in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China1 Guangming Zhang, Qishi Song2, and Darong Yang Kunming Section, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 88 Xuefu Road, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, Peoples’ Republic of China ABSTRACT Leaf and fig phenology (including leafing, flowering, and fruiting) and syconium growth of Ficus racemosa were studied in Xishuangbanna, China. Leaffall and flushing of F. racemosa occurred twice yearly: in mid-dry season (December to March) and mid-rainy season (July to September). The adult leaf stage of the first leaf production was remarkably longer than that of the second. F. racemosa bears syconia throughout the year, producing 4.76 crops annually. Asynchronous fig production was observed at a population level. Fig production was independent of leafing. Fig production peaks were not evident, but fluctuation was clear. Diameter growth rates of syconium were normally higher in early developmental stages than in later stages, and reached a peak coinciding with the female flower phase. The mean ± SD of syconium diameter of the female flower phase was 2.19 ± 0.36 cm, and reached 3.67 ± 0.73 cm of the male flower phase. Syconium diameter and receptacle cavity quickly enlarged at the female and male flower phases. Monthly diameter increment of the syconium was primarily affected by average monthly temperature, rather than rainfall or relative humidity. Key words: fig trees; leaffall; southern Yunnan; syconium. SEASONAL RHYTHM IS A BASIC CHARACTERISTIC OF LIFE (Zhu & Wan interfloral, male flower, and postfloral phases (Galil & Eisikowitch 1975).