Katharina Von Bora and Martin Luther

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Footsteps of Luther and Oberammergau

17 2020 DAYS Footsteps of Luther and Oberammergau 15 NIGHTS / 17 DAYS WED 29 JULY - FRI 14 AUG, 2020 Berlin (2) • Wittenberg (3) • Torgau • Eisleben • Erfurt (2) • Leipzig (3) • Dresden (2) • Munich (1) • Oberammergau (2) Accompanied by COMMENCES WEDNESDAY 29TH JULY 2020 Bishop Ross Nicholson Come Follow Me... Berlin Cathedral MEAL CODE streets with the rich timber framed buildings, Reformation, is waiting for us. We’ll tour the cross the merchant’s bridge, and take a (B) = Breakfast (L) = Lunch (D) = Dinner town where Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses look into the Old Synagogue. It’s the oldest to the door of the Schlosskirche on October 31, synagogue in Central Europe that has been DAY 1: WEDNESDAY 29TH JULY - DEPART 1517. In Luther’s time this was the University preserved up to its roof. The Museum displays AUSTRALIA FOR GERMANY Chapel and the doors were used as a bulletin the Erfurt Treasure and has the Erfurt Hebrew DAY 2: THURSDAY 30TH JULY – ARRIVAL board. Luther preached here and in the City Manuscripts as its central theme. We also BERLIN (D) Church of St. Mary. In 1508, when Martin visit the Augustinian monastery which Luther Luther came to Wittenberg, he lived in the Upon arrival at Berlin airport we will board our always referred to as his spiritual home. deluxe motor coach and head into the city to Black Abbey – now known as the “Lutherhaus”. Overnight: Erfurt our centrally located hotel, check in and rest It was here that he had his “Tower Experience” and first grasped the gift of faith by grace after a long day of travelling. -

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL Martin Luther

HAVE GERMAN WILL TRAVEL Martin Luther Martin Luther (der 10. November 1483-der 2. Februar 1546) Martin Luther came this way. Yet it is Wittenberg, a feisty university in effect, the metaphorical last straw. Wittenberg, Eisleben is now Lutherstadt town since the days of Frederick the The pulpit formerly stood in the Eislebeo and Mansfeld is Mansfeld Wise, that has never stopped proudly Parish Church of St. Mary where he was Lutherstadt. All are UNESCO World statinrr its claim as "Cradle of the Refor- married and where the four-paneled Heritage Sites today, and Saxony-Anhalt mation.""' Its name is officially Luther- Reformation altar in the Choir Room is has adopted the subtitle "Luther's Coun stadt Wittenberg, and here he received attributed to Lucas Cranach the Elder t1y" for its tourist promotions. his doctor's degree; lived and taught for (1472 to 1553) , onetime mayor of the His commitment meant nearly con nearly forty years. Luther's House town. stant traveling throughout central Ger (Lutherhaus, Collegianstrasse 54), t~e Under the Communists, noxious fac many. It was not an easy life, but he Augustinian Monastery where he resid tories lined the Elbe, and Wittenberg never hesitated to go where he was ed with his family after its religious dis was called "Chemical-town," but, to no needed or to speak the doctrine to his solution, contains Lutherhalle, the one's surprise, the name never caught people. world's largest museum of Reformation on. Even as the Wall was coming down in In the cold winter of 1546, Luther's history. -

Whenever Someone Speaks of Martin Luther, Everyone Thinks Of

Whenever someone speaks of The buildings in By 1519, Torgau’s Nikolai Four years later, the new Elector I sleep extremely Johann Walter compos- Martin Luther often preached in Even if I knew that tombstone we can see the image of Making a sad and Martin Luther, everyone thinks of Torgau are more Church was the scene of the John Frederick the Magnanimous, well, about 6 or 7 ed a motet for seven the town church of St. Mary’s, and tomorrow the world a self-confident, strong woman. despondent man Wittenberg, still many others think beautiful than any first baptism in the German who had succeeded his father John hours in a row, and voices for the consecra- altogether more than forty times would go to pieces, It is also worth visiting the house happy again, of Wartburg Castle, but only sel- from ancient times, language. One year later, Ger- in 1532, passed an edict to protect later again 2 or 3 tion. As a close friend of of a stay in Torgau can be verified. I would still plant my Katharinenstrasse 11, where you this is more than to dom of Worms. Even Eisleben and even King Solomon’s man was first used in a Pro- the printing of the complete Bible in hours. I think it is Luther’s, he had already Thus the saying that “Wittenberg apple tree today. find a museum, which is comme- conquer a kingdom. Mansfeld, where the great Refor- temple was only built testant sermon. Wittenberg. He then gave orders to because of the beer, edited the first new song was the Mother of Reformation and morating the wife of the great Re- mer was born and where he died, of wood. -

In the Footsteps of Martin Luther in Germany: 500 Years of Reformation

Wartburg College Alumni Tour In the Footsteps of Martin Luther in Germany: 500 Years of Reformation June 7-21, 2017 15 Days with optional extension to Bavaria June 21-24 Led by the Rev. Dr. Kit Kleinhans Group Travel Directors Enriching Lives Through Travel Since 1982 DAY-BY-DAY ITINERARY On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther Dr. Kit Kleinhans is Day 1, Wed, June 7 Your Journey Begins posted 95 theses against indul- the Mike and Marge Depart US for overnight flight to Berlin. (Meals in- McCoy Family Dis- flight) gences on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany – an tinguished Chair of Day 2, Thur, June 8 Herzlich Willkommen! event ranked as one of the most Lutheran Heritage and Arrive in Berlin and travel to Wittenberg by pri- important events of the millennium! Mission at Wartburg vate motor coach. Check into Colleg Wittenberg, College, where she our home for the next 6 days. After an orientation Celebrate the 500th anniversary of walk through the town, a welcome dinner will has taught since 1993. get us off to an excellent start. Colleg Wittenberg Luther’s bold action by following in Her passion is the (Meals in-flight, D) his footsteps. Visit Eisleben, where history and theology Day 3, Fri, June 9 Wittenberg Luther was born; Wittenberg, where of Lutheranism and its relevance for us City tour through Wittenberg, where Martin Lu- he taught; Worms, where he stood today. Her article “Lutheranism 101,” pub- ther lived and taught for 36 years. Visit the Luther up for beliefs against the leaders of lished in The Lutheran in 2006, remains House - a former monastery – where Luther lived before his marriage and which the Luther family the church and the empire; the Wart- the most frequently requested reprint received as a wedding gift from their prince. -

Übersichtsartikel

DAS LUTHERHAUS IN EISENACH Von Michael Weise Das Lutherhaus in Eisenach ist eines der ältesten erhaltenen Fachwerkhäuser Thürin- gens. Hier wohnte Martin Luther nach der Überlieferung bei der Familie Cotta wäh- rend seiner Schulzeit von 1498 bis 1501. Seit dem 19. Jahrhundert zählt das Luther- haus zu den bedeutendsten Gedenkstätten der Reformation und wurde in dieser Ei- genschaft 2011 als „Europäisches Kulturerbe“ ausgezeichnet. Seit 1956 wird das Lu- therhaus als kulturhistorisches Museum betrieben. Inhalt 1. Geschichte ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Luther in Eisenach .................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Luther als Schüler in Eisenach (1498–1501) ................................................. 2 1.1.2 Luther in der Georgenkirche (April/Mai 1521) ............................................ 2 1.1.3 Luther auf der Wartburg (Mai 1521–März 1522) ......................................... 3 1.1.4 Luthers letzte Aufenthalte in Eisenach (1529 und 1540) ............................. 4 1.2 Baugeschichte des Lutherhauses.............................................................................. 4 1.3 Museumsgeschichte .................................................................................................. 5 1.3.1 Das Lutherhaus von 1956–2013 .................................................................... 5 1.3.2 Das neue Lutherhaus (2013 bis heute) ........................................................ -

Zum PDF-Download

q 500 Jahre Reformation Luther Martin Martin Superstar — Dossier »Reformationsjubiläum Nr. 1« Martin Luther, Heinz Zander, Öl auf Hartfaser, 1982 95 Thesen Am 31. Oktober 1517 schrieb Martin Luther, der sich bereits in Predigten gegen den Ablasshandel ausgesprochen hatte, einen Brief an seine kirchlichen Vorgesetzten in der Hoffnung, damit den Missstand beheben zu können. Den Briefen legt er 95 Thesen bei, die als Grundlage für eine Disputation zu diesem Thema dienen sollten. Dass Luther seine Thesen mit lauten Hammerschlägen an die Tür der Schlosskirche zu Wittenberg geschlagen haben soll, ist jedoch umstritten. Editorial Von Himmel und Hölle, von Gnade so oder anders, von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen, von den ersten Schritten zur Aufklärung bis zum unheiligen Paktieren von Protestantismus und Staat, von der deutschen Sprache bis zur Nation, vom Bildersturm bis zum Erblühen der protestantischen Kirchenmusik, 1. die Reformation, die vor 499 Jahren in Wittenberg ihren Als unser Herr Ausgang nahm, hat die Welt verändert. Aber nicht nur und Meister Jesus im großen Ganzen ist die Reformation Motor des Wan- Christus sagte: dels, auch das Verhältnis des Einzelnen zu Gott hat sich »Tut Buße, denn fundamental erneuert. Zwischen Gott und den Men- das Himmelreich schen steht nicht mehr immer ein professioneller kirch- ist nahe herbei licher Glaubensverkünder, der den vermeintlich rich- gekommen«, wollte tigen Weg vorgibt, sondern das Priestertum aller Gläu- er, dass das ganze bigen hat den Weg zu Gott für Protestanten merklich Leben der Glauben verkürzt, wenn auch nicht unbedingt vereinfacht. Die den Buße sei. Reformation brachte den Gläubigen den Zugang zur Heiligen Schrift, doch dafür musste man Lesen und Ver- stehen können. -

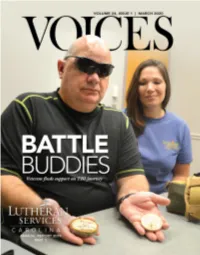

MARCH 2020 3 Christopher Otten Has Been Helping Trinity View Residents with Their Technology Ques- Tions for Over a Year

1 VOICES on goins By Ted W. Goins, Jr. | LSC president We were made for more utheran Services Carolinas always we did not win! Generally, it’s not necessary At St. John’s Lutheran Church in Salis- seems to be marching to its own for you to lose so I can win. If we approach bury, Pastor Rhodes Woolly preached on drummer, and I wouldn’t have it any our issues together and through the lens February 2 that “you were made for more.” other way. In a time period when civility of abundance versus scarcity, we can have That drives home The LSC Way. We in and truth and loving one another are out a better ministry and a better country and LSC are made for more in how we care for of style, when society is daily subjected to world. and serve people, from foster children to rudeness, lies, what’s in it LSC doubled down on this philosophy refugees to seniors! We can also expect the for me and to heck with in 2019 by creating The LSC Way. Already, best from each other, support each other, you, LSC lifts its Vision, more than 1,500 of LSC’s 2,000 teammates and not look to pull people down. And we Mission, and Values even have been through the training. You’ve can model The LSC Way at home, in our higher. heard about this program; it’s more exciting communities, and in our world. Our value of integrity to see it in action. We created a program Wouldn’t it be a better world with more is a cornerstone of our that pulls what is the very best from our integrity, trust, and love? The LSC Way is ministry. -

December 2019

ZION LUTHERAN CHURCH 420 1st Street SE PO Box 118 Gwinner, ND 701.678.2401 www.ziongwinner.org Pastor Aaron M. Filipek December 2019 Blessed Saints of Zion, In This Issue… We continue with our year long series of newsletter articles highlighting some saints of the Christian Church. For more information, please see the following LCMS website explaining a few things concerning saints, among other things: Saints of the Church (https://www.lcms.org/worship/church-year/commemorations) Mission of the Month I encourage you to read the biographies (along with the Scripture verses) of the saint on the appointed day. I pray this year long series of newsletter articles accomplishes three things: Food Pantry Needs 1) we thank God for giving faithful servants to His Church 2) through such remembrance our faith is December Birthdays strengthened as we see the mercy that God extended to His saints of old Congregation at Prayer 3) these saints are examples both of faith and of holy living to imitate according to our calling in life Catechesis Christ’s Peace, Pastor Aaron M. Filipek Christmas Schedule December 4: John of Damascus Service Lists John (ca. 675–749) is known as the great compiler and summarizer of the orthodox faith and the last great Greek theologian. Born in Damascus, John gave up an influential position in the Islamic court to devote himself to the Christian faith. Around Calendar 716 he entered a monastery outside of Jerusalem and was ordained a priest. When the Byzantine emperor Leo the Isaurian in 726 issued a decree forbidding images (icons), John forcefully resisted. -

Museen Und Ausstellungen 2018 Bis 2020

MUSEEN UND AUSSTELLUNGEN 2018 BIS 2020 INFORMATIONEN FÜR REISEVERANSTALTER / BUSTOURISTIK / GRUPPEN , stiftung Luthergedenkstätten in sachsen-anhalt Inhalt / Content Seiten / Pages Öffnungszeiten & Preise / Opening Hours & Prices 4–7 Service & Buchung / Service & Booking 8–9 Sonderausstellungen / Special Exhibitions 10–15 Standorte der Stiftung / Our Locations 16–19 Anfahrt / Travel Information 20 HERAUSGEBER Stiftung PUBLISHED BY Luther Memorials Luthergedenkstätten in Sachsen-Anhalt Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt www.martinluther.de www.martinluther.de Konzeption und Redaktion: Editors: Carola Schüren and Kerstin Kiehl Carola Schüren und Kerstin Kiehl Design: www.heilmeyerundsernau.com Grafik: www.heilmeyerundsernau.com Stand März 2018 Stiftung Luthergedenkstätten in Sachsen-Anhalt www.martinluther.de HIGHLights 2018–2020 BAUEN FÜR LUTHER 1998–2018. Wittenberg – EISLeben – MANSFELD 25.05.2018–04.11.2018 | AUGUSTEUM | LUTHERSTADT WITTENBERG VEREHRT. GELIEBT. VERGESSEN MARIA ZWISCHEN DEN KONFESSIONEN 12.04.2019–18.08.2019 | AUGUSTEUM | LUTHERSTADT WITTENBERG KETZER ! BRENNEN FÜR DIE waHRHEIT 04.04.2020–16.08.2020 | AUGUSTEUM | LUTHERSTADT WITTENBERG stiftung Luthergedenkstätten in sachsen-anhalt www.martinluther.de Stiftung Luthergedenkstätten in Sachsen-Anhalt LUTHERSTADT WITTENBERG LUTHERHAUS / LUTHER HOUSE ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN UND PREISE / OPENING HOURS & PRICES April–Oktober täglich von 9.00–ı8.00 Uhr November–März ı0.00–ı7.00 Uhr, montags geschlossen April to October daily from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. November to March from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. – closed Mondays EINZELTICKET / INDIVIDUAL TICKET 8 € EINZELTICKET ERMÄSSIGT / DISCOUNTED ADMISSION 6 € SCHÜLER (6 BIS 16 JAHRE) / SCHOOLCHILDREN (AGE 6–16) 5 € Kinder bis 6 Jahre haben freien Eintritt / Children 6 and under free of charge GRUPPENTICKET (AB 10 PERSONEN) / GROUPS (10 OR MORE PEOPLE) 6 € pro Person / per person FamILIENKARTE / FAMILY TICKET 14 € Führungen ab 10 bis max. -

Luthers Hochzeit Fast Ein Halbes Jahrtausend Ist Es Her, Dass Der Ehemalige Mönch Martin Luther Die Aus Dem Kloster Entfl Ohene Nonne Katharina Von Bora Heiratete

Schön wie nie ! Wussten Sie’s schon? Die Lutherstadt Wittenberg Luthereiche steht natürlich für Luthers Die Luthereiche steht am südlichen Ende der Collegienstraße, dort, wo Martin Luther 1520 Thesenanschlag von 1517. die Bannbulle des Papstes verbrannte. ... aber auch für einige erstaunliche und manche kuriose Begebenheiten. 973 wurde das Territorium der heutigen Lutherstadt Urgroßvater 220 Hektar Wittenberg erstmals erwähnt. umfasst die Werksfl äche des Agro-Chemie Parks. des Handys Berlin oder Leipzig? Dank 1833 konstruiert Wilhelm Weber der ICE-Verbindung kann zusammen mit Carl Friedrich Gauß den ersten elektromagne- man entspannt in der tischen Telegrafen. Das Geburts- Hauptstadt frühstücken, haus des berühmten Stadtsohnes, das Weber-Haus, steht in der 30 in Lutherstadt Wittenberg Schlossstraße 10. mittagessen und abends in Minuten Leipzig tanzen. Sprechen Sie 1915 Luther? im April wurde der Luthers Redewendungen und Zitate haben sich tief in unserer Sprache Grundstein für den Piesteritzer verankert. Viele sind für uns heute ganz selbstverständlich und uns ist nicht Chemiestandort gelegt. bewusst, dass sie ursprünglich aus Luthers Mund stammten: „In den sauren Hier ist heute Deutschlands Apfel beißen“, „Auf eigene Faust“, „Berge versetzen“, „Hochmut kommt größter Ammoniak- und vor dem Fall“, „Hummeln im Arsch“, „Denkzettel“, „Das passt wie die Harnstoff produzent ansässig. Faust aufs Auge“ usw. Kaum einem ist es je so gut gelungen, menschliche Charaktereigenschaften und Beobachtungen über das Zusammenleben derart präzise auf den Punkt zu bringen wie Martin Luther. IMPRESSUM HERAUSGEBER Lutherstadt Wittenberg Marketing GmbH GESCHÄFTSFÜHRUNG Giorgos Kalaitzis PROJEKTLEITUNG Franka List REDAKTION Lutherstadt Wittenberg Marketing GmbH Ã [email protected] + 49 3491 419 260 2. Überarbeitung 2019 BILDNACHWEIS Soweit nicht anders vermerkt, liegen die Rechte aller in diesem Heft abgebildeten Fotos bei der Lutherstadt Wittenberg Marketing GmbH (Fotografen: Johannes Winkelmann, Corinna Kroll, Jan P. -

Invite Official of the Group You Want to Go

Tour #1 (6 nights / 8 days) Day 1 Depart via scheduled air service to Berlin, Germany. Day 2 Berlin / Wittenberg (D) Arrive in Berlin. Meet your MCI Tour Manager, who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Wittenberg via Juterborg for a visit to Nikolaikirche. Johann Tetzel was a preacher in Juterborg who sold absolution of sins to help the Archbishop of Mainz to pay off the debts he had incurred in securing the agreement of the Pope to his acquisition of the Archbishopric. It is believed that Martin Luther was inspired to write his Ninety-Five Theses, in part, due to Tetzel's actions. Continue to Wittenberg for a panoramic tour including the marketplace, Stadtkirche, Lutherhaus, Schloßkirche, etc. Hotel check-in. Evening Welcome Dinner and overnight. Wittenberg is located on Elbe River. It was a medieval center, famed as the birthplace of the Reformation. Wittenberg is of such importance in Luther's life that its official name is Lutherstadt- Wittenberg (Luther City Wittenberg). Day 3 Wittenberg (B,D) Sightseeing in Wittenberg includes entrance to the Lutherhalle, a museum of the Reformation. In the room occupied by Luther, preserved in its original condition, are displayed Luther's writings, prints, medals, Luther's university lectern, his pulpit from St Mary's Church and a number of valuable pictures. Also visit the Schlosskirche. From the church’s tower there are extensive views. It was to the wooden doors of this church that Luther nailed his 95 "Theses" in October 1517. The original doors were destroyed by fire during the Seven Years War; the present bronze doors, bearing the Latin text of the Theses, were installed in 1858. -

Info-Flyer Bildungsangebote

FRANKFURT BUCHUNG | KONTAKT EISENACH LUTHERHAUS „Unterricht wie zu Luthers Zeiten“ und „Luthers Werkstatt“ MÜNCHEN EISENACH 70,00 € für eine Schüler- oder Konfirmandengruppe 90,00 € für eine Erwachsenengruppe Die Materialkosten sind im Preis enthalten. BERLIN M: [email protected] BILDUNG | EDUCATION T: +49 (0) 3691 29 83-0 / +49 (0) 3691 29 83-26 Bitte beachten Sie unsere Anmeldefrist von 14 Tagen im Voraus. Verspätung / Stornierung Bei einer Verspätung von bis zu 20 Minuten findet das gebuchte Angebot Bildnachweise / picture credits: Sascha Willms holiday vacation from Dec. 24 through Jan. 1. on Sundays Open and holidays except for Betriebsferien 24. Dez. bis 1. Jan. Sonn- und Feiertage ohne Ausnahme geöffnet, Tues geschlossen montags Dienstag – Sonntag: Uhr, – 17 10 November – März / Monday – Sunday: a.m. 10 – 5 p.m. Montag – Sonntag: Uhr – 17 10 April – Oktober / HOURS / ÖFFNUNGSZEITEN closed Mon zeitlich verkürzt statt. Verspätet sich die Gruppe um mehr als 20 Minuten, erlischt der Anspruch auf die Buchung bei voller Gebühr. day – Sun Bei einer Stornierung bis 48 Stunden vor Angebotsbeginn wird keine Stor- nogebühr in Rechnung gestellt, erfolgt sie bis zu 24 Stunden vorher, werden 50% des Gesamtpreises fällig. Bei einer späteren Stornierung müssen die days vollen Kosten getragen werden. day: a.m. 10 – 5 p.m., April – Oct – April Stand: September 2016 Novem Änderungen und Irrtümer vorbehalten. ber – March RESERVATIONS | CONTACT ober “School in Luther’s Day” and “Luther’s Workshop” € 70 per group of school students or confirmands € 90 per group of adults The fee includes the cost of materials. www.lutherhaus-eisenach.de MORE INFORMATIONEN MEHR M: T: +49 3691 (0) 29 83-0 | F: +49 3691 (0) 29 83-31 Lutherplatz 8, Eisenach 99817 Stiftung Lutherhaus Eisenach M: [email protected] [email protected] P: +49 (0) 3691 29 83-0 / +49 (0) 3691 29 83-26 Please note that you must register no later than 14 days in advance.