The Wittelsbach Electors in Eighteenth-Century Bavaria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Adam R. Gustafson June 2011 © 2011 Adam R. Gustafson All Rights Reserved 2 This dissertation titled The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria by ADAM R. GUSTAFSON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts _______________________________________________ Dora Wilson Professor of Music _______________________________________________ Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GUSTAFSON, ADAM R., Ph.D., June 2011, Interdisciplinary Arts The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria Director of Dissertation: Dora Wilson Drawing from a number of artistic media, this dissertation is an interdisciplinary approach for understanding how artworks created under the patronage of Albrecht V were used to shape Catholic identity in Bavaria during the establishment of confessional boundaries in late sixteenth-century Europe. This study presents a methodological framework for understanding early modern patronage in which the arts are necessarily viewed as interconnected, and patronage is understood as a complex and often contradictory process that involved all elements of society. First, this study examines the legacy of arts patronage that Albrecht V inherited from his Wittelsbach predecessors and developed during his reign, from 1550-1579. Albrecht V‟s patronage is then divided into three areas: northern princely humanism, traditional religion and sociological propaganda. -

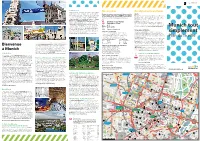

Munich Tout Simplement

3 Neues Rathaus 11 Hofbräuhaus Le Kunstareal Nos services Reseignements pratiques Le quartier muséal se caractérise par une concentration et une diversité exceptionnelles de musées et de galeries situés à proximité d‘univer- München Tourismus propose un large éventail de ressources et de Accès sités et d‘institutions de renom. L‘expérience culturelle s‘intègre ici dans services de qualité – personnalisés et multilingues – pour organiser Par avion: Franz-Josef-Strauß Flughafen MUC. Transfert à Munich avec un espace urbain dynamique, agrémenté de bistrots branchés, de jolies un séjour à Munich avec une grande diversité d‘activités culturelles les lignes de S-Bahn S1 et S8 (durée du trajet env. 40 min) ou bien boutiques et de zones de repos verdoyantes. L‘Alte Pinakothek 1 , et de loisirs, de détente et de plaisir purement munichois. Airport Bus jusqu‘au Hauptbahnhof (durée du trajet env. 45 min). Taxi. la Neue Pinakothek 2 et la Pinakothek der Moderne 3 , le Museum Avec le train: München Hauptbahnhof, Ostbahnhof, Pasing Brandhorst 4 et l‘Ägyptisches Museum 5 ainsi que les musées En voiture: A8, A9, A92, A95, A96. situés autour de la Königsplatz: 6 la villa Lenbachhaus 7 , les Informations sur Munich/ Depuis 2008, il existe une zone verte à Munich: elle comprend le Staatliche Antikensammlungen 8 (musée bavarois des Antiquités), Réservation d‘Hotel centre-ville à l‘intérieur du Mittlerer Ring (mais pas le périphérique la Glyptothek 9 et le NS-Dokumentationszentrum 10 hébergent lui-même). Seuls les véhicules avec une pastille écologique verte sont ensemble un répertoire inestimable d‘art, de culture et de savoir repré- Lu-Ve 9h-17h Téléphone +49 89 233-96500 autorisés à rouler dans la zone. -

Munich Including Large Pull-Out Map & 80 Stickers for Individual Planning

Munich Including large pull-out map & 80 stickers for individual planning English Edition 0094_Muenchen_oc_ic_E.indd 1 22.03.16 09:32 Munich Author Karin Baedeker Including large pull-out map & 80 stickers fal- for individualkeits- planning rche Löwen- Promenade- www.polyglott.degr. platz 34 Ettstr. Frauenpl. 5 4 Marien- Hof- grab Am Weinstr. hof 39 Kosttor 37 Färber- 2 r. Kaufinger- t s str. str. n 1 40 e Platzl38 Dienerstr. 38 Hildegardstraße 51 assa degardstraßeegegaardstraße g Marienplatz r. k B graben rä aßaße n r L i MariMarMarien-ririenn-n st a ed s uh r. t R g p e r. t - straßet aße re - s - S g r platplapplatzatzatz u r . s r Burgstr.Burgst tr e r . HerrnstraßeHerrHerrnstr e b m l ll el- 3 - m r.- nst o i Hacken- Ta b M traß St Hofstatt 20 l aße W ochb ar ß - Knöbel-KöbKnöb Hochbr.-HochbH ie s str. 19 ns a tr. Tal m delgdel 14 Str. o Adelgundenstr.Adelgundenst H.- R ViktualViktualieVViktualien-iktualien-tuaualallienienn- h erSack- Oberangero s 21 T gStr en marktm k 22 Mannnn- in 15 tal Radlsteg 2604_Muenchen_E.indd 1 dl IsartIIsartor-aartortor- Sebastians-nns- Westenriederstr. plpplatzaatztz platz Isartorartortor tr. 188 Frauen- s aße . tr LäLän r chs t iers n sstr. h T r. ststr.tr. st d-d herrstherr Liebherrstr.LiebherrstLieb e 05.02.16 15:29 6 Local Flair SPOTLIGHTS 8 Munich Is Well Worth a 28 Children Visit! 53 Nightlife 11 Travel Barometer 62 Modern Architecture 12 50 Things that You… 66 Oktoberfest 19 What’s behind it? 160 Munich Checklist FIRST CLASS! 32 The Most Beautiful Bathing 20 Travel Planning Places & Addresses 37 -

U-Umgebungsplan Marienplatz

A B C D E F G H Herulessaal ofgarten Lenachlatz Kultus- straße Prannerstraße Salatorstraße isari N40 Klinium roßhadern ministerium Rohusstraße gasse 1 Frstenried est Cuillis- Theater Maimiliansplatz Lenachlatz 1 1 19 Pasing R reifaltigeits- R esiden e 21 Westfriedhof e N s Umgebungsplan irche s i Komdie im i N19 Pasing d d eonsplatz e Bayerischen Hof e z n Lenachlatz Paellistraße n llerheiligen- z z s 19 Berg am aim Bf. s Local area map t Hofirche U t Marstall r r a 21 St.-Veit-Straße a ß ß platz U St.-Veit-Straße e N19 e arinalaulhaberStraße Promenaeplatz Theatinerstraße Maxburg arienlatzheatinerstraße Lenachlatz (mtsgericht) 1 Pasing esidentheater Marstall N40 Kieferngarten Ehemalige 1 Westfriedhof Marienplatz 1 Feldmoching Bf. armeliterirche N1 Pasing atinaltheater 2 Ma- 1 Pasing 2 Maburgstraße 1 Westfriedhof armeliter oseph 1 straße Perusastraße N1 Pasing Rathaus Touristeninformation Maffeistraße Platz AlfonsoppelStraße Marienplatz 8 engrube artmann ationaltheater E4 Ausgang Exit straße atinaltheater (Bayerische Staatsoper) 1 Berg am aim Bf. arienlatzheatinerstraße Orientierung leicht gemacht Easy orientation inenmaher 1 St.-Veit-Straße straße 1 Berg am aim Bf. apellenstraße Shrammerstraße Maimilianstraße Marstallstraße fflerstraße 1 St.-Veit-Straße N1 St.-Veit-Straße 1. Nutzen Sie das Straßenverzeichnis, um den 1. Use the street directory to find SScchhä passenden Ausgangsbuchstaben zu finden the appropriate exit letter N1 St.-Veit-Straße 2. Folgen Sie „Ihrem“ Buchstaben auf den Schildern 2. Follow „your“ letter in the signage ttstraße -

LOCAL RECOMMENDATIONS EARLI SIG 1 2016 Conference

LOCAL RECOMMENDATIONS EARLI SIG 1 2016 Conference CULTURE CITY GUIDES “WEIS(S)SER STADTVOGEL” The “old town”- tour starts at “Marienplatz” (12€; you don’t need to register). More tours can be found at: www.weisser-stadtvogel.de MVV-Station: Marienplatz CITYSIGHTSEEING City tour in a double-decker: You can book different tours (ca. 12.90€; from 10am to 5pm; departure every 10-20 min).The departures of all tours start at the “Bahnhofsplatz” outside “Elisenhof” near Munich Central Train Station Further information at: http://www.citysightseeing-munich.com/ MVV-Station: Hauptbahnhof FREE CITY TOUR IN ENGLISH Join a city tour in Munich for free! The guides live from their tip.Meeting point is at “Marienplatz”, More tours e.g. Dachau, Neuschwanstein castle available for a small charge Further information at: www.newmunichtours.com MVV-Station: Marienplatz RADIUS TOURS & BIKE RENTAL Join a guided bike tour in English or just rent a bike to explore Munich on your own for 14.50€/day at Radius Tours Office, in Munich Central Train Station, daily 8.30am – 8pm Further information at: http://radiustours.com/index.php/en/english-tours Address: Arnulfstraße 3 MVV-Station: Hauptbahnhof RICKSHAW TOUR Enjoy a ride through Munich in a rickshaw. There are guides in several languages. Further information at: www.muenchen-rikscha.de Departure: Englischer Garten, Odeonsplatz, Marienplatz. MVV-Stations: University, Odeonsplatz, Marienplatz SIGHTS MARIENPLATZ, ALTER PETER AND VIKTUALIENMARKT Be sure to visit Marienplatz, the heart of Munich and its historic district! If you are there, climb up the church tower of “Alter Peter” and have a look at Munich from above. -

THE SPIRIT of a PALACE : Its Role for the Preservation of the Munich Residence

THE SPIRIT OF A PALACE Its Role for the Preservation of the Munich Residence HERMANN J. NEUMANN Bayerische Schlösserverwaltung Schloss Nymphenburg 16 D-80638 München Germany [email protected] Abstract. The Munich Residence in the heart of the bavar- ian capital, severely damaged during World War II, has suf- fered several losses of its tangible heritage during the 600 years of its existence. But the thesis should be allowed that the special tradition and historic character, the nurture of the fine arts as well as stately representation, or in short: the dignity of this place allowed the central palace of the Wit- telsbach family to outlast the centuries in a special quality – including its building fabric. But the reverse proposition should be represented in this text as well: that it is the pru- dent preservation of the palace’s outside, its characteristic layout and interior that offered the opportunity to preserve the sense of a cultural and historic center at this place. Fu- ture risks for the adequate preservation of this palace can only be mastered if the specific spirit of the Residence is the guideline for both responsible maintenance and adequate uses of the building. Roots and Development of a “Spirit of the Munich Residence” Bavaria proudly looks back on more than 1,400 years of history. The complicated tradition of its governments and the corresponding resi- dences goes beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to know that the Wittelsbach dynasty that governed Bavaria from 1180 to 1918 made Munich its single residence in 1506, developing the palace into one of the most splendid centers of power in central Europe. -

Munich City Map 1 Preview

A B C D E F G H J K L M N O P Q R S T U V Olympiapark 0200m Adalbertstr N# r (see inset) (2.5km) Munich 00.1miles Akademie k der Bildenden ee r Künste C h c A Olympiapark a m D b T os r tr s tlerst r u e t i c 1 K# s her e 1 Olympiazentrum in E l BMW Massmannpark Schelli g p l i ar A n k - ngstr A ö Englischer Plant winds kad K n em n Ad iestr Garten r BMW alb t a Sch e S M rts - Dachauer r r A Museum lphstr tr s t e a s BMW Welt A u r E a m e o u n h audo g h a l c T n g Str is s e Georg-Brauchle-Rin H r z -Ring es c i r Georg-Brauchle ss Schr h t n tr H e ie r s Spiridon-Louis-Ring Holareidulijö A r G d P a n St White Rose r la r te f e Memorial n If r r t a g Massmannstr S B A Professor- e r 2 2 Arcisstr -W Lerchenauer Str e Alter Simpl %A Huber-Platz Ti Olympia Park # v r Kufsteiner rd m K Universität o a A AInfo-Pavilion i Theresienstr Ludwig- lis a o e # t s B Complex K K r I Platz - reittmayrstr h n Maximilian- Geschwister- r ia Olympiaberg s t r ll s s t i i Universität Scholl-Platz Ve s K L Rock terin n r e ä e u l rst r e h l Museum h g Olympiaturm A A MonopterosA Ma rc s c Sc n i t i Olympic k e h t S e x r A Olympiapark r ll t i Theresiens ing -Josep e n Stadium s e r u tr r t a e O t r r s (150m) s r M tr k h S Munich G Neue Pinakothek A r e -B ab a y t e nstr p rü r (main map) lsb r a erg do ck A SeaLife (2.5km) erst eo m e Dachauer Str r Technische h n T e sstr r Türke M tgela Universität d on st str r i r M A Olympiasee tr tr e K# s W ö gustenstr München s h K hl 3 n hst c 3 g e i c a a st Olympia-Schwimmhalle -

Ski the Austrian Alps $2890* Per Person Includes Meals, Last Night in Munich & All Taxes

Ski the Austrian Alps $2890* per person includes meals, last night in Munich & all taxes Solden, located in the Otztal Valley, and one of The four star Europe's most renowned Ski & Snowboard Sporthotel Alpina is centrally located and Resorts. The infinite number of slopes & trails offers fast & easy access for all levels and abilities, coupled with the to the cable cars. The perfect grooming of not less than 150 km of hotel provides a shuttle slopes make Solden a truly unique winter sports bus service to the ski center. State-of-the-art ski lifts & gondolas with lifts in the morning and a total capacity of 68,000 persons/hour guarantee it is possible to ski directly back to the hotel. ultimate skiing fun without queuing. The wide variety of ski runs provides ultimate skiing for The hotel is located just off the main road, by the picturesque village church. After a hard day on the both beginners and advanced skiers. mountain, you will want to experience the hotel’s Snow is absolutely guaranteed from October Wellness Centre which includes a whirlpool, steam through May thanks to the ski area's high Alpine rooms and sauna. There is also a restaurant, bar and location, 2 glacier ski areas and snow making lounge area systems covering all slopes lower than 2,200 m. Gourmet cuisine at the Alpina: A day of sports in the Oetztal Valley requires a nourishing start to the day, a Solden has the marvelous BIG 3 vantage points - hearty snack and a delicious meal to round it off. -

•Intro • Unterwegs

•Intro München Impressionen 6 Heimeliges Weltstädtchen ® Reise-Video München 11 8Tipps für cleveres Reisen 12 Feiern, tanzen, Schurken jagen 8 Tipps für die ganze Familie 14 Klettern, kicken, Forscher spielen • Unterwegs Die Altstadt - im Bannkreis der goldenen Madonna 18 H Marienplatz 19 ® Reise-Video Marienplatz 20 KB Neues Rathaus 20 EI Altes Rathaus 21 ©Audio-Feature Altes Rathaus 21 KM Spielzeugmuseum 21 19 Heiliggeistkirche 21 B St. Peter 23 MM Rindermarkt 24 O Hofer 25 O Alter Hof 25 IEI Hofbräuhaus 26 ® Audio-Feature Hofbräuhaus 26 •II Alte Münze 27 IB Eilles-Hof 27 IS Max-Joseph-Platz 28 •fil Nationaltheater 29 US Residenztheater 30 IQ Residenz 31 ® Reise-Video Residenz 33 Ufl Residenzmuseum 33 na Schatzkammer der Residenz 38 IE! Cuvilliös-Theater 40 Efil Hofgarten 41 EU Kunstverein München 44 El Deutsches Theatermuseum 44 EEI Feldherrnhalle 45 El Preysing-Palais 46 El Theatinerkirche 47 ® Reise-Video Theatinerkirche 48 El Fünf Höfe 48 EM Literaturhaus 49 El Salvatorkirche 49 El Palais Portia 50 B!l Erzbischöfliches Palais 51 Hl Palais Neuhaus-Preysing 51 13 Palais Gise 51 http://d-nb.info/1050182820 BEI Palais Montgelas 51 BEI Museum Brandhorst 88 El Gunetzrhainerhaus 52 El Museum Reich der Kristalle 89 ES Dreifaltigkeitskirche 52 ELI Wittelsbacher Platz 89 EEI Wittelsbacher Brunnen 53 El Odeonsplatz und Ludwigstraße 90 ES Künstlerhaus 54 EEI Odeon 91 EU Justizpalast 55 Ell Leuchtenberg-Palais 92 E£l Alter Botanischer Garten 55 ES Bazargebäude 92 ES Karlstor mit Rondellbauten 55 ES Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv 93 ED Brunnenbuberl 56 ES Bayerische Staatsbibliothek 93 ES Bürgersaal 57 ES St. Ludwig 94 ES Augustinerbräu 58 ES Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität 95 ES St. -

Simply in the Museum 22 Popular Munich Museums with Tips Simply Seeing More Simply in the Museum

simply in the Museum 22 popular Munich museums with tips simply seeing more Simply in the museum... Arrival, Approach, Attention, At the start, A like Altdorfer, Antiquity, Answers, And so on, Anger, Anthropocene, Architecture, Armor, Art Nouveau, Art Quarter, Automobile, Avant-garde, Barberini Faun, Battered, Beer, Beuys, Biedermeier, Bruno the Bear, Candelabra, Cappuccino, Caravaggio, Cars are the Stars, Conrad Röntgen, Cembalos, Cheese Cake, Cherubs, Cribs, Decoration, Design, Disney, Dix, Dürer, E=mc², Egyptomania, Elephants, Enlightenment, Fat and Felt, FC Bayern, Focused, Franz von Stuck, Gaultier, Geo Zoo, Goose Bumps, Graf- fiti, Grüß Gott, Harry Klein goes Kunsthalle, High Voltage, Hops and Malt, Immaculate Conception, Kiefer, Kinetic Sculpture, King Niuserre, Kritzikratzi, Le Corbusier, Leonardo, Lion, Love, Ludwig I, Man is Good – People are Bad, Modern Media, Microcosm, Morris Dancers, Mozart, My Favorite Picture, Myths, Naiads, Nazareth, Neo Rauch, New Neighborhoods, Nymphs, Obscene, Pablo Picas- so, Patron Goddess, Porcelain Shops, Pompous Furniture, Princes of Painting, Prosecco, Puffing Billy, Pumuckl, Random Patterns, Richard Riemerschmid, Ring my bell, Space Patrol, Street Art, Sub- marine, Sun, Moon and Stars, Timeless, Track, Twittering Machine, Twombly, Typically Munich, Ultramarine Blue, Valentin, Warhol, Wax, We are who we are, Whip into Shape, Wittelsbach dynasty, Would be suitable for the Livingroom, Wow, Wright Brothers, Xanthippe, Xylography, Yad, Yellow Cow, Zak, Zampa, Zeitgeist, Zephyr, Zest, from A to Zett ...simply in the museum 1 Museum Brandhorst Theresienstraße 35a Tue, Wed, Fri, Sat, Sun 10am – 6pm Thu 10am – 8pm The Brandhorst collection comprises more than 1,000 works by path-breaking artists of the 20th and 21st centuries such as Cy Twombly, Andy Warhol, Sigmar Polke, Damien Hirst and Mike Kelley. -

Gaststätten Und Restaurants in Der Innenstadt Pubs and Restaurants in the City Centre a B C D E F G

Wirteplan_01_12 neu.qxd 10.11.2012 23:40 Uhr Seite 1 A B C D E F G H I Gaststätten und Restaurants in der Innenstadt Pubs and restaurants in the city centre A B C D E F G 1 Andechser am Dom A Von der Neuen Messe München D-3 Weinstraße 7a, Telefon 089/29 84 81, (Haltestelle Messestadt West) erreichen Sie mit täglich 10.00-1.00 Uhr, Küche 10.00-24.00 Uhr der U2 in nur 20 Minuten die Innenstadt. 2 Augustiner Großgaststätten Die U-Bahn-Linie U2 fährt im 10-Minuten-Takt – C-3 Neuhauser Straße 27, Telefon 089/2 31 832 57, bei Großmessen sogar im 5-Minuten-Takt. 1 täglich 10.00-24.00 Uhr, warme Küche 11.00-23.00 Uhr 3 Ayingers am Platzl 1a F-3 Telefon 089/23 7 0 36 66, täglich warme Küche 11.00-23.30 Uhr 4 Bratwurstherzl am Viktualienmarkt E-4 Dreifaltigkeitsplatz 1, Telefon 089/29 51 13, D täglich 10.00-23.00 Uhr, Sonn- und Feiertage geschlossen 5 Woerners Cafehäuser D-3 Marienplatz 1, Telefon 089/22 27 66, Montag-Freitag 8.00-19.30 Uhr, Samstag 8.00-19.00 Uhr, B Sonn- und Feiertage 10.00-18.00 Uhr, Im Sommer auch länger geöffnet. 6 Augustiner am Platzl 2 E-3 Orlandostraße 5, Telefon 089/211 13 56, täglich 10.00-24.00 Uhr C 7 Hofbräuhaus F-3 Platzl 9, Telefon 089/290 136 100, täglich 9.00-23.30 Uhr 8 Pfälzer Residenz Weinstube E-2 Residenzstraße 1, Telefon 089/22 56 28, täglich 10.00-0.30 Uhr, warme Küche 11.00-23.00 Uhr E I 9 Restaurant Zum Alten Markt E-4 Dreifaltigkeitsplatz 3, Telefon 089/29 99 95, Montag-Samstag 11.00-24.00 Uhr F 10 Ratskeller am Marienplatz 23 E-3 Restaurant • Bistro • Weinbar 3 Marienplatz 8, Telefon 089/219 98 90, 24 -

Museen in München

Aktionstage Infopoint Special Days & Offers Museen & Schlösser in Bayern • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Haus der Kunst ALTER HOF 1 • 80331 MÜNCHEN Jeden 1. Donnerstag im Monat freier Eintritt/ +49( 0 ) 89 210140-50 free entrance every 1st Thursday of the month [email protected] 18-22 Uhr INFOPOINT-MUSEEN-BAYERN.DE Kunsthalle München: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Montag–Samstag 10–18 Uhr 50% Ermässigung auf alle Eintrittspreise am Dienstag/ an Sonn- und Feiertagen geschlossen 50% off entrance fee on Tuesday Reduzierter & freier Eintritt Eintritt frei Villa Stuck: Friday Late Reduced & free admission Jeden 1. Freitag im Monat freier Eintritt/ blog.museumsperlen.de into Munich’s museums free entrance every 1st Friday of the month #museeninbayern 18-22 Uhr @InfopointBayern • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Valentin-Karlstadt Musäum: • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Jeden 1. Freitag im Monat Programm und • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Abendöffnung/special events 1st Friday of the month • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • bis 21:59 Uhr • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •