Mr. Wrigley's Ball Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

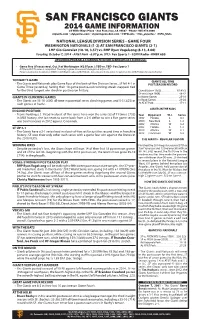

NLDS Notes GM 4.Indd

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME INFORMATION 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats NATIONAL LEAGUE DIVISION SERIES - GAME FOUR WASHINGTON NATIONALS (1-2) AT SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (2-1) LHP Gio Gonzalez (10-10, 3.57) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (8-13, 4.00) Tuesday, October 7, 2014 • AT&T Park • 6:07 p.m. (PT) • Fox Sports 1 • ESPN Radio • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Game Five (if necessary), Oct. 9 at Washington (#2:07p.m.): TBD vs. TBD- Fox Sports 1 # If the LAD/STL series is completed, Thursday's game time would change to 5:37p.m. PT Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio) and ESPN Radio. All postseason home games broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). TONIGHT'S GAME GIANTS ALL-TIME • The Giants and Nationals play Game Four of this best-of- ve Division Series...SF fell 4-1 in POSTSEASON RECORD Game Three yesterday, having their 10-game postseason winning streak snapped, tied for the third-longest win streak in postseason history. Overall (since 1900) . 87-83-2 SF-era (since 1958) . .48-42 GIANTS IN CLINCHING GAMES In Home Games . .25-18 • The Giants are 15-10 (.600) all-time in potential series clinching games and 5-3 (.625) in In Road Games. .23-24 such games at home. At AT&T Park . .17-11 GIANTS IN THE NLDS IN GOOD POSITION • Teams holding a 2-1 lead in a best-of- ve series have won the series 52 of 71 times (.732) Year Opponent W-L Series in MLB history...the last team to come back from a 2-0 de cit to win a ve game series 1997 Florida L 0-3 was San Francisco in 2012 against Cincinnati. -

NEIGHBORHOOD PROTECTION REPORT Dear Neighbors

2019 NEIGHBORHOOD PROTECTION REPORT Dear Neighbors, Thank you for your support of the Chicago Cubs in 2019. Each year, we are proud to share with the community our efforts aimed at protecting and enhancing the quality of life for Lakeview residents, while ensuring the fan and visitor experience at Wrigley Field is the best in baseball. The work to expand and preserve Wrigley Field continued this year and the Cubs reached new levels in support for community and charitable activities. Through our investment of more than $1 million, we helped reduce traffic congestion in the area, proactively communicated to residents about events and activities in the neighborhood and helped keep our community clean and safe. Our notable achievements in 2019 are highlighted in this report. Among them: • Nearly 54,000 fans used the remote parking lot at 3900 N. Rockwell Street and took the shuttle bus to and from Wrigley Field, helping alleviate traffic in the neighborhood. • Nearly 4,000 bicyclists took advantage of the free valet service down the block from the ballpark, further reducing traffic and air pollution in the area. • Our neighborhood newsletter provided regular updates about events inside and outside the ballpark, including impacts to parking, traffic in the area and construction activity. • We continued to help deter crime and keep our neighborhood clean by funding programs such as Safe at Home and trash removal in Lakeview. We also are proud of our investments in the community. In 2019, the Cubs and Cubs Charities supported millions of dollars in charitable grants and donations to deserving nonprofit organizations in the neighborhood and throughout Chicago. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Cubs Daily Clips

April 6, 2016 CSNChicago.com, After all the hype, Jon Lester ready to roll with Cubs http://www.csnchicago.com/cubs/jon-lester-already-showing-noticeable-progression-year-2-cubs CSNChicago.com, Cubs will face some interesting decisions with Jorge Soler http://www.csnchicago.com/cubs/cubs-will-face-some-interesting-decisions-jorge-soler CSNChicago.com, Back with Cubs, Dexter Fowler playing like he has something to prove http://www.csnchicago.com/cubs/back-cubs-dexter-fowler-playing-he-has-something-prove Chicago Tribune, Jon Lester regains old form in leading Cubs to 6-1 victory over Angels http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-jon-lester-report-cubs-angels-spt-0406-20160405- story.html Chicago Tribune, Cubs may be baseball's first team with its own laugh track http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/columnists/ct-cubs-silliness-sullivan-spt-0406-20160405-column.html Chicago Tribune, Joe Maddon's iPad gets early season workout http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-joe-maddons-ipad-gets-early-season-workout- 20160405-story.html Chicago Tribune, Cubs' Matt Szczur stays compact but provides big results http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-matt-szczur-plays-big-20160405-story.html Chicago Tribune, Tuesday's recap: Cubs 6, Angels 1 http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-gameday-cubs-angels-spt-0406-20160405- story.html Chicago Tribune, Cubs prospect Duane Underwood Jr. playing catch-up http://www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-duane-underwood-jr-healing-20160406-story.html -

The 112Th World Series Chicago Cubs Vs. Cleveland Indians Saturday, October 29, 2016 Game 4 - 7:08 P.M

THE 112TH WORLD SERIES CHICAGO CUBS VS. CLEVELAND INDIANS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2016 GAME 4 - 7:08 P.M. (CT) FIRST PITCH WRIGLEY FIELD, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 2016 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 25th CLE 6, CHI 0 Kluber Lester — 38,091 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 26th CHI 5, CLE 1 Arrieta Bauer — 38,172 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 28th CLE 1, CHI 0 Miller Edwards Allen 41,703 2016 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH TV/RADIO 4 Saturday, October 29th Wrigley Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 5 Sunday, October 30th Wrigley Field 8:15 p.m. ET/7:15 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 31st OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, November 1st Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, November 2nd Progressive Field 8:08 p.m. ET/7:08 p.m. CT FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary 2016 WORLD SERIES PROBABLE PITCHERS (Regular Season/Postseason) Game 4 at Chicago: John Lackey (11-8, 3.35/0-0, 5.63) vs. Corey Kluber (18-9, 3.14/3-1, 0.74) Game 5 at Chicago: Jon Lester (19-5, 2.44/2-1, 1.69) vs. Trevor Bauer (12-8, 4.26/0-1, 5.00) SERIES AT 2-1 CUBS AT 1-2 This is the 87th time in World Series history that the Fall Classic has • This is the eighth time that the Cubs trail a best-of-seven stood at 2-1 after three games, and it is the 13th time in the last 17 Postseason series, 2-1. -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Jimmy Johnston Earns Amateur Golftitle

SPORTS AND FINANCIAL Base Ball, Racing Stocks and Bonds Golf and General Financial News l_ five Jhinttmi fKtaf Part s—lo Pages WASHINGTON, 13. C., SUNDAY MORNING, SEPTEMBER 8, 1929. Griffs Beat Chisox in Opener, 2—l: Jimmy Johnston Earns Amateur Golf Title VICTOR AND VANQUISHED IN NATIONAL AMATEUR GOLF TOURNAMENT ¦¦ '¦ * mm i 1 11—— 1 I ¦¦l. mm MARBERRY LICKS THOMAS 1 i PRIDE OF ST. PAUL WINS IN FLASHY MOUND TUSSLE | ....... OYER DR. WILLING, 4 AND 3 i '<l \ j u/ Fred Yields Hut Six Hits and Holds Foe Seoreless JT Makes Strong Finish After Ragged Play in Morn- Until Ninth—Nats Get Seven Safeties—Earn ing to Take Measure of Portland Opponent. W '' ' / T Executes - of One Run, Berg Hands Them Another. /. / 4- jr""'"" 1 \ \ Wonder Shot Out Ocean. / 5 - \ \ •' * 11 f _jl"nil" >.< •*, liL / / A \ BY GRAXTLAND RICE. BY JOHN B. KELLER. Thomas on MONTE, Calif., September 7.—The green, soft fairway of MARBERRY was just a trifle stronger than A1 Pebble Beach the a new amateur as White Sex A \ caught footfall of champion the pitching slab yesterday the Nationals and f this afternoon. His name is Harrison ( series of the year ( Jimmy) Johnston, the clashed in the opening tilt of their wind-up PBHKm DELpride of St. Paul, who after a game, up-hill battle all through charges scored a 2-to-l victory that FREDand as a result Johnson’s \ morning fought his way into victory the grim, hard- back of the fifth-place Tigers, the crowd wtik the round, over left them but half a game fighting Doc Willing of Portland, Ore., by the margin of 4 and 3. -

![1939-07-14 [P B-6]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5819/1939-07-14-p-b-6-485819.webp)

1939-07-14 [P B-6]

■■■ Reds Bob Up With Bigger Lead Than Yankees as Start Second Half ■ Majors y Sports Mirror Lose or Draw Champions Drop Hartnett Draws Bv MM Auoclatod Preu. Win, Today a year ago—Lefty Grove, star Red Sox pitcher, forced out By FRANCIS E. STAN. 6th in Row as of game in sixth inning with First Blood in sudden arm ailment as he won An Authority Speaks on Joe Gordon 14th game of season. Three United If it did nothing else, baseball's latest all-star show exposed the ln- years ago—Full States team of 384 athletes as- flelding greatness of Joe Gordon for all to see. The young Yankee second Bosox Win sured for Berlin Olympics as baseman emerged sharing the heroics with Bob Feller, who is getting some Cub-Phil Feud women’s track team raised funds recognition of his own, and around the country now the critics are saying to send IS. that Gordon is the No. 1 man at his position. National Pacemakers Five years ago—Cavalcade won Bill Reinhart was talking about the youngster a few days before the Trounces Club Irked $30,000 Arlington Classic, beat- all-star game. Reinhart is George Washington's football and basket ball Blank Giants, Go ing Discovery by four lengths; Because Lou Gehrig, ill with coach and one of the two men who know Gordon best. The other is Arny Idled lumbago, kept record of in- Manager Joe McCarthy of the Yankees. 6V2 Games Up string games At 'Dream' Game tact by batting in first inning for • “He's the finest .young ballplayer I ever saw at the start of his career,” JUDSON BAILEY, Yanks. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

American Hercules: the Creation of Babe Ruth As an American Icon

1 American Hercules: The Creation of Babe Ruth as an American Icon David Leister TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas May 10, 2018 H.W. Brands, P.h.D Department of History Supervising Professor Michael Cramer, P.h.D. Department of Advertising and Public Relations Second Reader 2 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………...Page 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….Page 5 The Dark Ages…………………………………………………………………………..…..Page 7 Ruth Before New York…………………………………………………………………….Page 12 New York 1920………………………………………………………………………….…Page 18 Ruth Arrives………………………………………………………………………………..Page 23 The Making of a Legend…………………………………………………………………...Page 27 Myth Making…………………………………………………………………………….…Page 39 Ruth’s Legacy………………………………………………………………………...……Page 46 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….Page 57 Exhibits…………………………………………………………………………………….Page 58 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….Page 65 About the Author……………………………………………………………………..……Page 68 3 “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” -The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance “I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big. I like to live as big as I can” -Babe Ruth 4 Abstract Like no other athlete before or since, Babe Ruth’s popularity has endured long after his playing days ended. His name has entered the popular lexicon, where “Ruthian” is a synonym for a superhuman feat, and other greats are referred to as the “Babe Ruth” of their field. Ruth’s name has even been attached to modern players, such as Shohei Ohtani, the Angels rookie known as the “Japanese Babe Ruth”. Ruth’s on field records and off-field antics have entered the realm of legend, and as a result, Ruth is often looked at as a sort of folk-hero. This thesis explains why Ruth is seen this way, and what forces led to the creation of the mythic figure surrounding the man. -

Wrigley Field

Jordan, J. The Origination of Baseball and Its Stadiums 1 Running header: THE ORIGINATION OF BASEBALL AND ITS STADIUMS The Origination of Baseball and Its Stadiums: Wrigley Field Justin A. Jordan North Carolina State University Landscape Architecture 444 Prof. Fernando Magallanes December 7, 2012 Jordan, J. The Origination of Baseball and Its Stadiums 2 Abstract Baseball is America’s Pastime and is home for some of the most influential people and places in the USA. Since the origination of baseball itself, fields and ball parks have had emotional effects on Americans beginning long before the creation of the USA. In this paper, one will find the background of the sport and how it became as well as the first ball parks and their effects on people in the USA leading up to the discussion about Wrigley Field in Chicago, Illinois. Jordan, J. The Origination of Baseball and Its Stadiums 3 Baseball. This one word could represent the American pastime and culture. Many believe it to be as old as dirt. Peter Morris in his book, Level Playing Fields, explains “Baseball is sometimes said to be older than dirt. It is one of those metaphors that sounds silly on its face but that still resonates because it hints at a deeper truth. In this case, the deeper truth is that neither baseball nor dirt is quite complete without the other” (Morris, 2007). Morris practically says that baseball cannot thrive without proper fields to play on or parks to play in. Before describing early playing fields and stadiums in baseball, one must know where the sport and idea originated from in the first place.