Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copernicus Park

Approximate boundaries: N-W. Grange Ave;S -W. Ramsey Ave; E-I-94, W-S. 27th St FAR SOUTH SIDECopernicus Park NEIGHBORHOOD DESCRIPTION Copernicus Park is a moderate-density neighborhood. Home architectural styles are mainly 1950s/ 1960s ranch houses and Cape Cods, with a scattering of Tudor style homes. The neighborhood topography is hilly with a few steep hills. Most of the streets follow a grid pattern, except for few winding thoroughfares such as South 22nd and Klein Avenue that curve around the southern border of Copernicus Park. The business district is along South 27th Street--one of the major commercial corridors in the city. The street teems with fast food restaurants, strip malls, and car dealerships. The main green space is Copernicus Park, a 20-acre commons with a basketball court, tot lot, wooded area with a hiking trail, and a stream that runs through the park. See neighborhood photos below. HISTORY Copernicus Park is one far south side neighborhood among many that makes up today’s Garden District. The boundaries of the Garden District are those of the 13th Aldermanic District. All Garden District neighborhoods were once part of the Town of Lake, with boundaries of Lake Michigan to South 27th Street and Greenfield to College Avenues. By the mid-1950s, the City of Milwaukee had annexed the areas that today encompasses the Garden District. Early populations Many of the far south side neighborhoods that comprise today’s Todays neighborhood- Garden District owe a debt to the dreams of a local Norwegian Houses on 20th & Grange named John Saveland. -

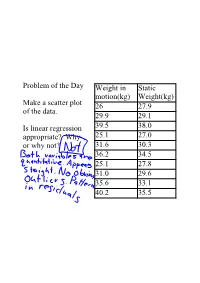

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

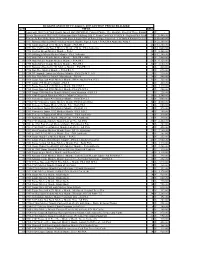

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

San Francisco Giants Weekly Notes: April 13-19

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS WEEKLY NOTES: APRIL 13-19 Oracle Park 24 Willie Mays Plaza San Francisco, CA 94107 Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com sfgigantes.com giantspressbox.com @SFGiants @SFGigantes @SFGiantsMedia NEWS & NOTES RADIO & TV THIS WEEK The Giants have created sfgiants.com/ Last Friday, Sony and the MLBPA launched fans/resource-center as a destination for MLB The Show Players League, a 30-player updates regarding the 2020 baseball sea- eSports league that will run for approxi- son as well as a place to find resources that mately three weeks. OF Hunter Pence will Monday - April 13 are being offered throughout our commu- represent the Giants. For more info, see nities during this difficult time. page two . 7:35 a.m. - Mike Krukow Fans interested in the weekly re-broadcast After crowning a fan-favorite Giant from joins Murph & Mac of classic Giants games can find a schedule the 1990-2009 era, IF Brandon Crawford 5 p.m. - Gabe Kapler for upcoming broadcasts at sfgiants.com/ has turned his sights to finding out which joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks fans/broadcasts cereal is the best. See which cereal won Tuesday - April 14 his CerealWars bracket 7:35 a.m. - Duane Kuiper joins Murph & Mac THIS WEEK IN GIANTS HISTORY 4:30 p.m. - Dave Flemming joins Tolbert, Krueger & Brooks APR OF Barry Bonds hit APR On Opening Day at APR Two of the NL’s top his 661st home run, the Polo Grounds, pitchers battled it Wednesday - April 15 13 passing Willie Mays 16 Mel Ott hit his 511th 18 out in San Francis- 7:35 a.m. -

Top Sluggers and Their Home Run Breakdowns

Best of Baseball Prospectus: 1996-2011 Part 1: Offense 6 APRIL 22, 2004 : http://bbp.cx/a/2795 HANK AARON'S HOME COOKING Top Sluggers and Their Home Run Breakdowns Jay Jaffe One of the qualities that makes baseball unique is its embrace of non-standard playing surfaces. Football fields and basketball courts are always the same length, but no two outfields are created equal. As Jay Jaffe explains via a look at Barry Bonds and the all-time home run leaderboard, a player’s home park can have a significant effect on how often he goes yard. It's been a couple of weeks since the 30th anniversary of Hank Aaron's historic 715th home run and the accompanying tributes, but Barry Bonds' exploits tend to keep the top of the all-time chart in the news. With homers in seven straight games and counting at this writing, Bonds has blown past Willie Mays at number three like the Say Hey Kid was standing still, which— congratulatory road trip aside—he has been, come to think of it. Baseball Prospectus' Dayn Perry penned an affectionate tribute to Aaron last week. In reviewing Hammerin' Hank's history, he notes that Aaron's superficially declining stats in 1968 (the Year of the Pitcher, not coincidentally) led him to consider retirement, but that historian Lee Allen reminded him of the milestones which lay ahead. Two years later, Aaron became the first black player to cross the 3,000 hit threshold, two months ahead of Mays. By then he was chasing 600 homers and climbing into some rarefied air among the top power hitters of all time. -

Greater Flint Area Sports Hall of Fame - Page 1 Greater Flint Area Sports Hall of Fame - Page 2 Tonight’S Program

28th Annual Greater Flint Area SpOrts Mali-vai Washington 1951 Flint mandeville Mike czarnecki Football team Bill hajec 1961 buick colts Todd lyght Baseball team Bob chipman Frank smorch 1983 & 1984 flint northwestern girls Tom Yeotis basketball teams Special service Award 2007 INDUCTION BANQUET Saturday, December 1, 2007 Genesys Conference & Banquet Center Grand Blanc, Michigan 2007 17 GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 1 GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 2 TONIGHT’S PROGRAM SOCIAL HOUR AND CASH BAR 5:30 to 6:30 Welcome, Introduction of Guests and Officers.....Tom Healey, President INTRODUCTION OF THE 2007 INDUCTEES Master of Ceremonies: Bill Troesken, Member Board of Directors Invocation: Rev. Roy Horning, Pastor of St. Robert Church-Flushing National Anthem: Choraleers from Carman-Ainsworth High School ENJOY YOUR DINNER Presentation of the Class of 2007.......................................Bill Troesken THE 2007 INDUCTEES Bill Hajec Bob Chipman Mali-Vai Washington Mike Czarnecki Todd Lyght Frank Smorch - Represented by his son, Frank Smorch Tom Yeotis - Special Service Award Flint Northwestern 1983 & 1984 Girls Basketball Teams Flint Mandeville 1951 Football Team Buick Colts 1961 Baseball Team Join us for Autographs and Afterglow by the Plaques GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 3 GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 4 GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 5 Foundation Flint Sports Hall AD_07 10/24/07 9:32 AM Page 1 THE FOUNDATION FOR Salutes Tom Yeotis A great MCC alumnus, a great citizen, a great athlete and a standout in every aspect of life. Congratulations on your Special Service Award from the Greater Flint Area Sports Hall of Fame. -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

Al Brancato This Article Was Written by David E

Al Brancato This article was written by David E. Skelton The fractured skull Philadelphia Athletics shortstop Skeeter Newsome suffered on April 9, 1938 left a gaping hole in the club’s defense. Ten players, including Newsome after he recovered, attempted to fill the void through the 1939 season. One was Al Brancato, a 20- year-old September call-up from Class-A ball who had never played shortstop professionally. Enticed by the youngster’s cannon right arm, Athletics manager Connie Mack moved him from third base to short in 1940. On June 21, after watching Brancato retire Chicago White Sox great Luke Appling on a hard-hit grounder, Mack exclaimed, “There’s no telling how good that boy is going to be.”1 Though no one in the organization expected the diminutive (5-feet-nine and 188 pounds) Philadelphia native’s offense to cause fans to forget former Athletics infield greats Home Run Baker or Eddie Collins, the club was satisfied that Brancato could fill in defensively. “You keep on fielding the way you are and I’ll do the worrying about your hitting,” Mack told Brancato in May 1941.2 Ironically, the youngster’s defensive skills would fail him before the season ended. In September, as the club spiraled to its eighth straight losing season, “baseball’s grand old gentleman” lashed out. “The infielders—[Benny] McCoy, Brancato and [Pete] Suder—are terrible,” Mack grumbled. “They have hit bottom. Suder is so slow it is painful to watch him; Brancato is erratic and McCoy is—oh, he’s just McCoy, that’s all.” 3 After the season ended Brancato enlisted in the US Navy following the country’s entry into the Second World War. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Mathematics for the Liberal Arts

Mathematics for Practical Applications - Baseball - Test File - Spring 2009 Exam #1 In exercises #1 - 5, a statement is given. For each exercise, identify one AND ONLY ONE of our fallacies that is exhibited in that statement. GIVE A DETAILED EXPLANATION TO JUSTIFY YOUR CHOICE. 1.) "According to Joe Shlabotnik, the manager of the Waxahachie Walnuts, you should never call a hit and run play in the bottom of the ninth inning." 2.) "Are you going to major in history or are you going to major in mathematics?" 3.) "Bubba Sue is from Alabama. All girls from Alabama have two word first names." 4.) "Gosh, officer, I know I made an illegal left turn, but please don't give me a ticket. I've had a hard day, and I was just trying to get over to my aged mother's hospital room, and spend a few minutes with her before I report to my second full-time minimum-wage job, which I have to have as the sole support of my thirty-seven children and the nineteen members of my extended family who depend on me for food and shelter." 5.) "Former major league pitcher Ross Grimsley, nicknamed "Scuzz," would not wash or change any part of his uniform as long as the team was winning, believing that washing or changing anything would jinx the team." 6.) The part of a major league infield that is inside the bases is a square that is 90 feet on each side. What is its area in square centimeters? You must show the use of units and conversion factors. -

Treasurer Michael Frerichs Announces Online Auction for Unclaimed Property Live Auction June 22-26, Sale Preview Underway

OFFICE OF ILLINOIS STATE TREASURER MICHAEL W. FRERICHS FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: June 8, 2015 Paris Ervin 217.524.5749 Greg Rivara 312.814.1901 Treasurer Michael Frerichs Announces Online Auction for Unclaimed Property Live Auction June 22-26, Sale Preview Underway SPRINGFIELD – Silver bars, commemorative coins, stamps, and jewelry are among the 9,500 items worth $76 thousand to be auctioned online June 22-26, Illinois Treasurer Michael Frerichs said today. “Our unclaimed property team works hard to return valuables to their rightful owners. If the property goes unclaimed for 10 years, the items are auctioned to make room for incoming unclaimed items,” Frerichs said. Other auction items include vintage cards of Stan Musial, Elvis Presley, and Elizabeth Taylor. Baseball Digest magazines with covers of Billy Williams, Johnny Bench, and Brooks Robinson also are available. Auction items have been appraised by an outside vendor. Auction participants can register at illinoistreasurer.gov and click on the Unclaimed Property Auction link. For questions, call 217.557-8567. The Illinois Treasurer’s office is the custodian of unclaimed property including lost bank accounts, insurance policy proceeds, and forgotten safe deposit boxes. Items are auctioned after private and public entities tried for at least 10 years to locate the owners. The office secures more than $2 billion in unclaimed property. Individuals can search by name at illinoistreasurer.gov or 217.785.6998. Because thousands of items are surrendered each year, residents should check every six months. Treasurer Frerichs’ office never charges money to search or return unclaimed property. Auction proceeds will be held for rightful owners until they are identified. -

SEATTLE MARINERS NEWS CLIPS April 8, 2010

SEATTLE MARINERS NEWS CLIPS April 8, 2010 Originally published April 7, 2010 at 10:13 PM | Page modified April 7, 2010 at 11:51 PM Mariners bullpen falters in 6-5 loss to Oakland Oakland's Kurt Suzuki drilled a deep fly ball past the glove of Milton Bradley at the left-field wall in the ninth inning, handing reliever Mark Lowe and the Mariners a 6-5 walkoff loss. By Geoff Baker Seattle Times staff reporter OAKLAND, Calif. - The realities of a six-man bullpen began hitting the Mariners about as hard as their opponent was by the time the fifth inning rolled around. It was clear by then that Seattle starter Ryan Rowland-Smith would have to scratch and claw just to make it through the minimum five innings his team desperately needed Wednesday night. After that, it was Russian roulette time, as the Mariners played a guessing game with their limited relief corps, squeezing every last pitch they could out of some arms. But they couldn't get the job completely done as Kurt Suzuki drilled a deep fly ball past the glove of Milton Bradley at the left-field wall in the ninth inning, handing reliever Mark Lowe and the Mariners a 6-5 walkoff loss. After the game, manager Don Wakamatsu suggested the team would have to call up another bullpen arm if a similar long-relief scenario occurs in Thursday's series finale. "We can't keep going like this," Wakamatsu said. The second walkoff defeat in two nights for the Mariners, in front of 18,194 at the Coliseum, has them crossing their fingers that starters Doug Fister and Jason Vargas don't implode these next two days.