Al Brancato This Article Was Written by David E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. CHAPTER 1 Fair Ball! Why Adjustments Are Needed King Arthur’s quest for it in the Middle Ages became a large part of his legend. Monty Python and Indiana Jones launched their searches in popular 1974 and 1989 movies. The mythic quest for the Holy Grail, the name given in Western tradition to the chal- ice used by Jesus Christ at his Passover meal the night before his death, is now often a metaphor for a quintessential search. In the illustrious history of baseball, the “holy grail” is a ranking of each player’s overall value on the baseball diamond. Because player skills are multifaceted, it is not clear that such a ranking is possible. In comparing two players, you see that one hits home runs much better, whereas the other gets on base more often, is faster on the base paths, and is a better fielder. So which player should rank higher? In Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, I identified which players were best at getting a hit in a given at-bat, calling them the best hitters. Many reviewers either disapproved of or failed to note my definition of “best hitter.” Although frequently used in base- ball writings, the terms “good hitter” or best hitter are rarely defined. In a July 1997 Sports Illustrated article, Tom Verducci called Tony Gwynn “the best hitter since Ted Williams” while considering only batting average. -

2017 Connie Mack League Rules A

2017 CONNIE MACK LEAGUE RULES A. TEAM ENTRY PROCEDURE: 1. Managers are required to submit their team entry card when entering their team. B. GAME FEES: 1. The Cleveland Baseball Federation pays all game fees for City of Cleveland teams. 2. Non-resident teams may only enter if room is available and they pay their game fees. “ PLAYER ELIGIBILITY AND REGISTRATION ” C. PLAYER ELIGIBILITY: 1. City of Cleveland residents have first priority on participating in this league. - Residency is defined when either parent or legal guardian lives in Cleveland. 2. Age Limit: Ages 19 and under, cannot turn 20 years old before August 1, 2017. 3. Non-residents can play: Each team may have (7) non-residents on their roster. 4. More than (1) team: Each team may have no more than (5) players who play on 2 teams. D. SQUAD SIZE: 1. The roster limit is 18 players for all leagues. E. CONTRACT CARDS: 1. Any coach who plays an illegal player and the illegal player will be suspended for (4) games. 2. Verified and approved contract cards must be available at all games. 3. Two contract cards must be validated at the Division of Recreation administrative office prior to the team’s first game between the hours of 9:00 a.m. and 4:30 p.m. 4. Minors must have a parent or legal guardian sign the contracts. 5. NO PICTURES are required on the contract cards. 6. Players must have a photo I.D. with him at each game. 8. Signing Deadline to add players: Teams may add players before July 1, 2017. -

Greater Flint Area Sports Hall of Fame - Page 1 Greater Flint Area Sports Hall of Fame - Page 2 Tonight’S Program

28th Annual Greater Flint Area SpOrts Mali-vai Washington 1951 Flint mandeville Mike czarnecki Football team Bill hajec 1961 buick colts Todd lyght Baseball team Bob chipman Frank smorch 1983 & 1984 flint northwestern girls Tom Yeotis basketball teams Special service Award 2007 INDUCTION BANQUET Saturday, December 1, 2007 Genesys Conference & Banquet Center Grand Blanc, Michigan 2007 17 GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 1 GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 2 TONIGHT’S PROGRAM SOCIAL HOUR AND CASH BAR 5:30 to 6:30 Welcome, Introduction of Guests and Officers.....Tom Healey, President INTRODUCTION OF THE 2007 INDUCTEES Master of Ceremonies: Bill Troesken, Member Board of Directors Invocation: Rev. Roy Horning, Pastor of St. Robert Church-Flushing National Anthem: Choraleers from Carman-Ainsworth High School ENJOY YOUR DINNER Presentation of the Class of 2007.......................................Bill Troesken THE 2007 INDUCTEES Bill Hajec Bob Chipman Mali-Vai Washington Mike Czarnecki Todd Lyght Frank Smorch - Represented by his son, Frank Smorch Tom Yeotis - Special Service Award Flint Northwestern 1983 & 1984 Girls Basketball Teams Flint Mandeville 1951 Football Team Buick Colts 1961 Baseball Team Join us for Autographs and Afterglow by the Plaques GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 3 GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 4 GREATER FLINT AREA SPORTS HALL OF FAME - PAGE 5 Foundation Flint Sports Hall AD_07 10/24/07 9:32 AM Page 1 THE FOUNDATION FOR Salutes Tom Yeotis A great MCC alumnus, a great citizen, a great athlete and a standout in every aspect of life. Congratulations on your Special Service Award from the Greater Flint Area Sports Hall of Fame. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Pender County Superintendent Allison Sholar to Serve As NCHSAA

NORTH CAROLINA HIGH SCHOOL ATHLETIC AssOCIATION BULLETIN Volume 62, Number 1 Fall 2009 Pender County Superintendent Allison Sholar To Serve As NCHSAA President For 2009-10 Academic Year CHAPEL HILL—Allison Sholar, among those nominees individuals are selected by the Nominating superintendent of the Pender County Committee to fill the available slots. They are approved by the mem- schools, will serve as president of the bership at the Annual Meeting. North Carolina High School Board of The new Board members nominated were either filling vacancies Directors for the 2009-2010 academic produced by members going off the Board due to completion of their year. terms or those who are off due to retirement or leaving public school Daryl Barnes, principal of the new work. They include from Region 1, Dwayne Stallings, superintendent Wheatmore High School in Randolph of Perquimans County schools (to replace Julius Walker’s unexpired County, has been named vice-president term); from Region 1, Herman Little, athletic director, Northeastern and Dr. Diane Frost, superintendent of High School (Class 2-A, Region 1, athletic director); from Region 3, Asheboro City Schools, will serve again Shelly Marsh, deputy superintendent, Johnston County schools (Class in the role as immediate past president 4-A, Region 3, athletic director); Ernie Purnsley, athletic director, since Dr. Bill Harrison, who served as Pinecrest High School (Class 4-A, Region 4, athletic director); Bill president during most of the 2008-2009 Miller, superintendent, Polk County schools (superintendent, Class NCHSAA President Allison school year, has retired. 1-A, Region 8). Re-nominated to a full term were Rexanna Lowman, Sholar is superintendent Born in Asheboro and a 1983 gradu- principal of East Burke High School (Class 4-A, Region 7), and Page of Pender County ate of Elon College, Allison taught high Carver, principal of Ashbrook High School (Class 4-A, Region 6). -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

PDF of August 1976 Issue

~CityWatch' is CTA System Bonus By Jeff Stern Chicago has an extra public service asset that reaches beyond transit, although transit is the reason it exists. You might call it a "round-the-clock com- munity alarm system" extending to every street and right-of-way that a CTA bus or train travels. "Alerts" are frequent as CTA bus operators and motormen get on the radiophone to report incidents on their routes which may warrant an emergency re- sponse from other city agencies. While "lookout" duty is not prescribed in the oper- ating rulebook, it is exercised continuously, demon- strating the outstanding sense of community responsi- bility that the CTA "volunteers" possess. The CTA Control Center in the Merchandise Mart has direct flip-a-switch contact with police and fire de- partments, city and state highway authorities and other service agencies. Alerts can be relayed to them almost instantaneously, giving extra assurance to citizens that help will come quickly when they need it. Recently, an operator on Lake Shore Drive called the Control Center to report that a plane approaching Meigs Field had fallen into Lake Michigan. It turned out that this was the first call to be relayed to the fire department about this accident. In another demonstration of concern, the operator of a 67th Street bus saw a woman who was trying to cross the street get hit by a truck. He immediately called the Control Center to send a fire ambulance to the scene. (Continued Page 2) Here's how C'TA's additional community service works. -

Nats Win at Last, Backing Good Pitching with Power to Trample

Farm,and Garden ■*•«**,Financial News __Junior Star_ 101(1^ Jgtflf jgptiTlg_Stomps _ WASHINGTON, I). C., APIIIL 21, 1946. :_■__ ___ Nats Win at Last, Backing Good Pitching With Power to Trample Yankees, 7-3 ★ ★ _____# ★ ★ ★ ★ ose or Assault Shines in Wood, Armed Lands Philadelphia at 'Graw By FRANCIS E. STANN --- 4 Heath's Benching Follows Simmons-Bonura Pattern AT LEAST ONE GOT BY —By Gib Crockett Test The benching of Outfielder Jeff Heath by the Nationals after Texas Ace Passes Derby less than a week of play is not without precedent. Heath, you re- Spence's Homer member, was acquired for one purpose—to hit that long, extra-base In Finish at Jamaica wallop for Washington. But so were A1 Simmons and Zeke Bonura Sizzling some years ago. Marine Simmons had been one of the greatest right- Heads Rips by Favored Hampden, Victory hand sluggers m the history of the American Slashing On to Win League. For that matter, iie may have been In Stretch, Goes 2-Length the absolute greatest. Critics generally rated By the Associated Press licked a $22,600 pay check for Simmons and Rogers Hornsby of the National f up 1 lis him a bank as 14-Hit NEW YORK, 20.—The Texas day's work, giving the two modern Attack League best of times. April ■oil of $30,100 for the year and The Milwaukee Pole was over the hill when terror from the wide open spaces,,’ 47,350 for his two seasons. Clark Griffith got him, but he still was a home Leonard, stretch-burning Assault, sizzled to a He’ll take the train ride to the run threat. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #92 VINTAGE HALL OF FAMERS ROOKIE CARDS SALE – TAKE 10% OFF 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron 1959 Topps #338 Sparky 1956 Topps #292 Luis Aparicio 1954 Topps #94 Ernie Banks EX- 1968 Topps #247 Johnny Bench EX o/c $550.00 Anderson EX $30.00 EX-MT $115.00; VG-EX $59.00; MT $1100.00; EX+ $585.00; PSA PSA 6 EX-MT $120.00; EX-MT GD-VG $35.00 5 EX $550.00; VG-EX $395.00; VG $115.00; EX o/c $49.00 $290.00 1909 E90-1 American Caramel 1909 E95 Philadelphia Caramel 1887 Tobin Lithographs Dan 1949 Bowman #84 Roy 1967 Topps #568 Rod Carew NR- Chief Bender PSA 2 GD $325.00 Chief Bender FR $99.00 Brouthers SGC Authentic $295.00 Campanella VG-EX/EX $375.00 MT $320.00; EX-MT $295.00 1958 Topps #343 Orlando Cepeda 1909 E92 Dockman & Sons Frank 1909 E90-1 American Caramel 1910 E93 Standard Caramel 1909 E90-1 American Caramel PSA 5 EX $55.00 Chance SGC 30 GD $395.00 Frank Chance FR-GD $95.00 Eddie Collins GD-VG Sam Crawford GD $150.00 (paper loss back) $175.00 1932 U.S. Caramel #7 Joe Cronin 1933 Goudey #23 Kiki Cuyler 1933 Goudey #19 Bill Dickey 1939 Play Ball #26 Joe DiMaggio 1957 Topps #18 Don Drysdale SGC 50 VG-EX $375.00 GD-VG $49.00 VG $150.00 EX $695.00; PSA 3.5 VG+ $495.00 NR-MT $220.00; PSA 6 EX-MT $210.00; EX-MT $195.00; EX $120.00; VG-EX $95.00 1910 T3 Turkey Red Cabinet #16 1910 E93 Standard Caramel 1909-11 T206 (Polar Bear) 1948 Bowman #5 Bob Feller EX 1972 Topps #79 Carlton Fisk EX Johnny Evers VG $575.00 Johnny Evers FR-GD $99.00 Johnny Evers SGC 45 VG+ $170.00; VG $75.00 $19.95; VG-EX $14.95 $240.00 KIT YOUNG CARDS • 4876 SANTA MONICA AVE, #137 • DEPT. -

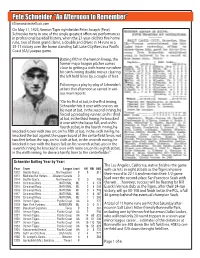

Pete Schneider

Pete Schneider, “An Afternoon to Remember” ©DiamondsintheDusk.com On May 11, 1923, Vernon Tiger rightfielder Peter Joseph (Pete) Schneider turns in one of the single greatest offensive performances in professional baseball history, when the 27-year-old hits five home runs, two of them grand slams, a double and drives in 14 runs in a 35-11 victory over the home standing Salt Lake City Bees in a Pacific Coast (AA) League game. Batting fifth in the Vernon lineup, the former major league pitcher comes close to getting a sixth home run when his sixth-inning double misses clearing the left field fence by a couple of feet. Following is a play-by-play of Schneider’s at bats that afternoon as carried in vari- ous news reports: “On his first at bat, in the first inning, Schneider hits it over with one on; on his next at bat, in the second inning, he forced a preceding runner; on his third at bat, in the third Inning, he knocked it over with the bases full; and on his fourth at bat, in the fourth inning, he knocked it over with two on; on his fifth at bat, in the sixth inning, he knocked the ball against the upper board of the centerfield fence, not two feet below the top; on his sixth at bat, in the seventh inning, he knocked it over with the bases full; on his seventh at bat, also in the seventh inning, he knocked it over with none on; on his eighth at bat, in the ninth inning, he drove a terrific liner to the centerfielder.” Schneider Batting Year by Year: The Los Angeles, California, native finishes the game Year Team League Level HR RBI AVG with six hits in eight at bats as the Tigers improve 1912 Seattle Giants ..................... -

1941-06-10 [P

GOOD MORNING VANDER MEER SPURS C1NCY REDS Swimming* BLOMME ACE MOUNDSMAN DODGERS By GLENWARD Conn’s Moved Right Along So Far, But Next-? DRoT AP Feature Service IS FINDING FORM a hitch in Conn’s waltz the trail to FROM on the lakes and eveiy been scarcely Billy along heavyweight NAT on the THERE’S It’s swimming time beaches, will LEU the when t ose date but the 180-pound (well, almost) challenger have to do some mighty foxy trot- shady creek hole. It is also the time of year about Old Grudges Forgotten As to his June 18 engagement with the head man of the heavies, Joe Louis. Red who love to hit the water are not cautious enough ting get by Cincinnati, Hot. noticeable increase Club Near- made his heavyweight debut, at scarcely more than 170 pounds, against Gus Do- Fast their health. Every summer there is a Johnny Clicks; Conn to Tumble which have been traced razio in 1939. He stopped Gus and since then has registered kayoes, technical or actual, Hap. in sinus, mastoid and ear infections ing Third Place less Brooklyns writers h over Bob Pastor, Danny Hassett, Gunnar Barlund, and Buddy Knox. He also has won to In swimming events sports swimming. ani are but are not. Fish have decisions over A1 McCoy, Henry Cooper Lee Savold. Here Conn and some of the called the contestants ‘fish,’ they By JUDSON BAILEY # BROOKLYN, June 9—ijl. use to c ® victims of his lead-up to Louis: red hot Cincinnati Reds which they _____ null./'1 protective covering f that^at BROOKLYN, June 9— UP)—John- ether They also posset extra fat victory out of the ?? trils before submerging.