44789 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

Deputy Commissioner/Chairman District Sand Monitoring Committee(Crz) Uttara Kannda District, Karwar- 581301 Karnataka State

APPENDIX I (See paragraph – 6) FORM 1 (I) Basic Information Sl. No. Item Details 1. Name of the project/s Removal of sand from Sand bar SB-GA-1 2. S. No. in the schedule 3. Proposed capacity/area/length/ tonnage to be handled/command 3.8 Ha. area/lease area/ number of wells to be drilled 4. New/Expansion/Modernization Not applicable 5. Existing capacity/area etc., 3.8 Ha. 6. Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ B 7. Does it attract the general condition? If yes, please specify No 8. Does it attract the specific condition? If yes, please specify No 9. Location Gangavali river, Plot/Survey/Khasra No. Gangavali River bed Village Sagadageri Tehsil Ankola District Uttara kannada State Karnataka 10. Nearest railway station/airport along with distance in Kms Gokarna railway station 2.0 Km 11. Nearest Town, city, District Headquarters along with distance in Ankola 7.3 KM Kms 12 Village Panchayats, Zilla Parishad, Municipal Corporation, Local Zilla panchayath, Uttara body (complete postal addresses with telephone nos. to be given) Kannada Dist, Karwar-581381 Tel: 08382-226560 13 Name of the applicant Deputy Commissioner/ Chairman District Sand Monitoring Committee Uttara Kannada District. 14 Registered Address Do 1 15 Address for correspondence: District sand Monitoring Committee, O/o the Deputy commissioner, Karwar. Name Deputy commissioner Designation (Owner/Partner/CEO) Chairman, District sand monitoring committee Address O/o the Deputy Commissioner, Karwar Pin Code 581381 E-Mail [email protected] Telephone No. 08382-226303 Fax No. 16 Details of Alternative Sites examined, if any. Location of these Village-District-State sites should be shown on a topo sheet. -

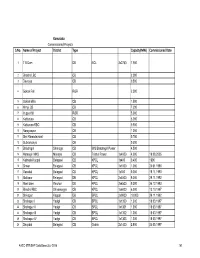

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 1 T B Dam DB NCL 3x2750 7.950 2 Bhadra LBC CB 2.000 3 Devraya CB 0.500 4 Gokak Fall ROR 2.500 5 Gokak Mills CB 1.500 6 Himpi CB CB 7.200 7 Iruppu fall ROR 5.000 8 Kattepura CB 5.000 9 Kattepura RBC CB 0.500 10 Narayanpur CB 1.200 11 Shri Ramadevaral CB 0.750 12 Subramanya CB 0.500 13 Bhadragiri Shimoga CB M/S Bhadragiri Power 4.500 14 Hemagiri MHS Mandya CB Trishul Power 1x4000 4.000 19.08.2005 15 Kalmala-Koppal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x400 0.400 1990 16 Sirwar Belagavi CB KPCL 1x1000 1.000 24.01.1990 17 Ganekal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x350 0.350 19.11.1993 18 Mallapur Belagavi DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 29.11.1992 19 Mani dam Raichur DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 24.12.1993 20 Bhadra RBC Shivamogga CB KPCL 1x6000 6.000 13.10.1997 21 Shivapur Koppal DB BPCL 2x9000 18.000 29.11.1992 22 Shahapur I Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1300 1.300 18.03.1997 23 Shahapur II Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1301 1.300 18.03.1997 24 Shahapur III Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1302 1.300 18.03.1997 25 Shahapur IV Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1303 1.300 18.03.1997 26 Dhupdal Belagavi CB Gokak 2x1400 2.800 04.05.1997 AHEC-IITR/SHP Data Base/July 2016 141 S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 27 Anwari Shivamogga CB Dandeli Steel 2x750 1.500 04.05.1997 28 Chunchankatte Mysore ROR Graphite India 2x9000 18.000 13.10.1997 Karnataka State 29 Elaneer ROR Council for Science and 1x200 0.200 01.01.2005 Technology 30 Attihalla Mandya CB Yuken 1x350 0.350 03.07.1998 31 Shiva Mandya CB Cauvery 1x3000 3.000 10.09.1998 -

Physical Features, Climate and Drainage of India Hand Outs

INDIA PHYSIOGRAPHIC DIVISIONS India is the seventh largest and second most populous country in the world. Its area is 2.4% of the total world area but about 16% of the entire human races reside in its fold. In population, only the mainland China exceeds that of India. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Bhutan form the well-defined realm of south Asia often referred to as the Indian sub-continent. Lying entirely in the northern hemisphere (tropical zone), the Indian mainland extends between the latitude -8°4' N to 37°6'N and longitude -68°7' E to 97°25'E. The southernmost point in the Indian territory, the Indira Point, is situated at 6°30' north in the Andaman and Nicobar islands. The tropic of cancer passes through the centre of India. India covers an area of 3.28 million sq km and measures about 3,214 km from north to south and about 2,933 km east to west. The total length of the mainland coastland is nearly 6,400 km and land frontier about 15,200 km. The boundary line between India and China is called the McMahon line. To the north-west, India, shares a boundary mainly with Pakistan and to the east with Myanmar and Bangladesh. The Indian Ocean lies in the south. In the south, on the eastern side, the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait separate India from Sri Lanka. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal and the Lakshadweep islands in the Arabian Sea are parts of the Indian Territory India's relief is marked by a great variety: India can be divided into five major physiographic units: 1. -

Community Strategies and Remedies for Natural Resource Conflicts in India CONTENTS

MIDCOURSE MANOEUVRES: Community strategies and remedies for natural resource conflicts in India Women walking aſter a day at coal mines in Hazaribagh, Jharkhand Centre for Policy Research (CPR)–Namati Environmental Justice Program June 2018 Author(s): Kanchi Kohli, Meenakshi Kapoor, Manju Menon and Vidya Viswanathan Citation: Kohli, K., Kapoor, M., Menon, M., & Viswanathan, V. (2018). Midcourse Manoeuvres: Community strategies and remedies for natural resource conflicts in India. New Delhi: CPR-Namati Environmental Justice Program This work has been carried out with the aid of a grant from the International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada About Centre for Policy Research (CPR) Editing and Proofreading: Ruchi Vadehra The Centre for Policy Research (CPR) has been one of India's leading public policy think tanks Photograph Credits: Joe Athialy, Maruti Gowda, Anjana John, Kanchi Kohli, Manju Menon, since 1973. The Centre is a nonprofit, independent institution dedicated to conducting research Vinod Patgar, Bipasha Paul, Manjit Yadav, Janabhiyakti and Centre for that contributes to a more robust public discourse about the structures and processes that Integrated Rural and Tribal Development (CIRTD) shape life in India. Contact Information: CPR-Namati Environmental Justice Program www.cprindia.org Centre for Policy Research Dharma Marg, Chanakyapuri About Namati New Delhi-110021 In a world where billions live outside the protection of the law, Namati is dedicated to putting the law in people's hands. It is building a global movement of grassroots legal advocates Design and Layout: Printforce who work with communities to advance justice. These advocates are fighting on the front Disclaimer: There is no copyright on this publication. -

ETR 129, Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES, Iisc

Karnataka’s Waterscape T.V. Ramachandra, Vinay S, Bharath S. and Bharath H. Aithal KARNATAKA– AT A GLANCE: Karnataka is one of the four southern states of Peninsular India (Figure 1a), came into existence with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act (1956, Nov 1) and is located 11°30' North and 18°30' North latitudes and 74° East and 78°30' East longitude (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geography_of_Karnataka). The state covers an area of 191,976 km² (5.83% of India’s geographical area). Karnataka is the eighth largest Indian state by area, the ninth largest by population and comprises 30 districts (figure 1b) divided in to 4 administrative divisions, 270 towns and 29406 villages (http://ssakarnataka.gov.in/). The state is situated on a table land where the Western and Eastern Ghats ranges converge into the complex, in the western part of the Deccan Peninsular region of India. Karnataka is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, Goa to the northwest, Maharashtra to the north, Andhra Pradesh to the east, Tamilnadu to the southeast, and Kerala to the southwest. Figure 1: Karnataka State, India with districts and River Systems RIVERS OF KARNATAKA: Rivers are a source of water for drinking, irrigation and electricity generation in Karnataka. Most of the rivers originate in the Western Ghats that generally flow westward meet the Arabian Sea after a short run varying from 50 kilometres to 300 kilometres. Almost all the major east- flowing rivers are inter-state rivers and runs towards the eastern side of the state and drain towards the Bay of Bengal. -

SCR28 ETR56 Land Use Land Cover (LULC) Dynamics in Uttara

Sahyadri Conservation Series 28 LAND USE LAND COVER (LULC) DYNAMICS IN UTTARA KANNADA DISTRICT, CENTRAL WESTERN GHATS Ramachandra T.V. Subash Chandran M.D Joshi N.V. Bharath Setturu Vector data Raster data (SurveyVectorof India datatopo sheets (LandsatRaster 1973, data 1979,1989, (Survey1:50000;1of:250000India, topo Frenchsheets (Landsat1999 & IRS1973, 2010, 1979,1989, 2013; 1Institute:50000;1map:2500001:250000, ,FrenchGPS) 1999 Google& IRS 2010,Earth) 2013; Institute map 1:250000 , GPS) Google Earth) Image pre processing Image pre processing GCP GCP Geometric Correction Field Data Geometric Correction Field Data (UTM zone:43N, WGS84) (UTM zone:43N, WGS84) Land use (LU) analysis Land cover (LC) analysis Land use (LU) analysis Land cover (LC) analysis (Supervised Classification) (NDVI) (Supervised Classification) (NDVI) Accuracy AccuracyAssessment Assessment Temporal Temporal land use Temporal Temporalmap land use Vegetation map map Vegetation map LULC Dynamics LULC Dynamics Western Ghats Task Force, Government of Karnataka Karnataka Biodiversity Board, Government of Karnataka The Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India The Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India ENVIS Technical Report: 56 July 2013 Environmental Information System [ENVIS] Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore - 560012, INDIA Web: http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/energy/ http://ces.iisc.ernet.in/biodiversity Email: [email protected], [email protected] LAND USE LAND COVER (LULC) DYNAMICS IN UTTARA KANNADA -

Location River GO No Date of Date of Turbin Capacity Capacity Allottment Cancellation Es (MW) (MW)

LIST OF SMALL HYDRO PROJECTS CANCELLED YEARWISE AS ON 31.07.2021. Sl No Company MHS Taluk District No of Allotted Cancelled Location River GO No Date of Date of Turbin Capacity Capacity Allottment Cancellation es (MW) (MW) 2003-2004 1 Trishul Yedehalli Bhadrava Shimoga 0.40 0.400 Yedehalli MHS Bhadra DE 132 NCE 97 20-04-1999 09-12-2003 Enterprises thi across Badhra river dated RBC 22nd 20/04/1999(0. disritubatory, 2 4 MW), DE NCE KM Chainage at 2002 dated Yedehalli Village 09/12/2003 of Bhadravathi (cancellation) Taluk in Shimoga District TOTAL 0.40 0.400 2006-2007 2 Adi Chikkama Mandya Mandya 0.75 0.750 Across VC canal DE 270 NCE 15-11-2006 15-11-2006 Chunchanagiri ndya near 2003 dated energy Projects Chikkamanday 31.12.2003 & Pvt. Ltd. Village, mandya DE 248 NCE Taluk, 2006 dt 15.11.2006, TOTAL 0.75 0.750 2007-2008 3 Aster Biligeri Somawar Kodagu 2.00 2.000 Across Madapur Madapu DE 210 NCE 09-09-2004 27-06-2007 Infrastructure apet Hole at Beiligiri r 2004 dated Pvt. Ltd. Village of Stream 9.9.2004 time Somwarpet extension GO. Taluk I Kodagu district 4 Handangaje Nalkur Sulya Dakshina 1.00 1.000 Nalkur Hole, a Nalkurh DE 288 NCE 14-10-2005 18-08-2007 Power Pvt. Ltd. Kannada minor tributory ole 2005 dated to the main Stream 14.10.2005, EN Kumaradhari 225 NCE 2007 river 18 Km from dated Subramanya 18/08/2007(ca near Devachala ncelled) Village of Sulya Taluk in Mangalore District. -

Karnataka Future Projects S. No. Name of Project District Type

Karnataka Future Projects S. Capacity Name of Project District Type No. (MW) Ajri Chikkamagalore Jasper Energy Pvt. Ltd. Dinnekere MHS across Dinnekere ROR DE 243 NCE 2003 dated 16.2.2004, EN 200 1 halla at Guttihalli Village of NCE 2010 dated 21/06/2010 (Cancelled) 1 Mudigere Taluk in Chikkamgalore District Alugodu Dakshina Kannada Neria Power Pvt. Ltd. Illimale MHS across Illimale CB DE 230 NCE 2002 dated 10/10/2002(0.5 MW), 4.5 2 Stream near Atturu Village, G.O. (4.5 MW) EN 173 NCE 2010 dated Belthangadi Taluk, 23/06/2010 (cancelled) Amruth Narayana Mandya Matha Hydro Power Ltd. Lokasara BC Kaveri K.R.S near CB DE 206 NCE 2004 dated 21/12/2004, EN 190 0.25 3 Lokasara Village, Arasanakere NCE 2010 dated 19/06/2010 (cancelled) Hobali, Asoga Belgaum Rio Energy Pvt Ltd across Ghataprabha Right Bank CB EN 329NCE 2012 04 01 2013(cancelled GO), 4 Canl at Hidkal Dam Village of EN 101 NCE 2012 dated 31.12.2012 4 Hukkeri Taluk in Belgaum district Baggadanalu yadgir Sai Teja Energues Private Across Bhima river at Yadgir, CB DE 155 NCE 2004 dated 9/9/2004, EN 197 1 5 Limited yadgir Taluk, NCE 2010 dated 23/06/2010 (cancelled) Baje Bangalore rural Magee Bail Enterprises Down stream of the ROR DE 46 NCE 2005 dated 22/03/2005, EN 195 0.4 6 Bhyramangala, Ramanagar Taluk, NCE 2010 dated 23/06/2010 (cancelled) Bangalore Rural District. Baluru Dakshina Kannada Pioneer Genco Ltd. Bazara MHS across Netravathi ROR DE 217 NCE 2005 dated 18/08/2005 (15 MW) 15 river near Bazara Village of Puttur EN 322NCE2012 dt 04.03.2013(cancelled) 7 Taluk in Dakshina Kannada District Balya Mysore Master Power, A Division Karmuddanahalli MHS, across ROR EN 202 NCE 2012 dated: 11/07/2012 1.75 of Master Services Pvt Ltd Karmuddanahalli stream, Cancelled vide GO.EN 72 NCE 2012 dated: 8 Karmuddanahalli Village, Hunsor 02.08.2013. -

(I) Basic Information

APPENDIX I (See paragraph – 6) FORM 1 (I) Basic Information Sl. No. Item Details 1. Name of the project/s Removal of sand from Sand bar SB-GA-2 2. S. No. in the schedule 3. Proposed capacity/area/length/ tonnage to be handled/command 7.55 Ha. area/lease area/ number of wells to be drilled 4. New/Expansion/Modernization Not applicable 5. Existing capacity/area etc., 7.55 Ha. 6. Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ B 7. Does it attract the general condition? If yes, please specify No 8. Does it attract the specific condition? If yes, please specify No 9. Location Gangavali river, Plot/Survey/Khasra No. Gangavali River bed Village Andle Tehsil Ankola District Uttara kannada State Karnataka 10. Nearest railway station/airport along with distance in Kms Gokarna railway station 2.5 Km 11. Nearest Town, city, District Headquarters along with distance in Ankola 10.7 KM Kms 12 Village Panchayats, Zilla Parishad, Municipal Corporation, Local Zilla panchayath, Uttara body (complete postal addresses with telephone nos. to be given) Kannada Dist, Karwar-581381 Tel: 08382-226560 13 Name of the applicant Deputy Commissioner/ Chairman District Sand Monitoring Committee Uttara Kannada District. 14 Registered Address Do 1 15 Address for correspondence: District sand Monitoring Committee, O/o the Deputy commissioner, Karwar. Name Deputy commissioner Designation (Owner/Partner/CEO) Chairman, District sand monitoring committee Address O/o the Deputy Commissioner, Karwar Pin Code 581381 E-Mail [email protected] Telephone No. 08382-226303 Fax No. 16 Details of Alternative Sites examined, if any. Location of these Village-District-State sites should be shown on a topo sheet. -

Ēĭʼōıē Ÿĕ Įęøĭĝ Æįđøēć

ēĭʼŌ ıĒ ÿĕ Įęøĭĝ æĮĐøēĆ (Đĭēć ĝēøĭē ÿĕ đŃũĭĕĒ øĸ æĮĊċˑ ĝļĝĭèĂı) NATIONAL WATER DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (A Society under Ministry of Water Resource, Govt. of India) PROPOSED BEDTI-VARADA RIVER LINK PROJECT TO PROVIDE IRRIGATION FACILITES FOR WATER DEFICIT AREAS OF TUNGABHADRA LEFT BANK CANAL, RAICHUR DISTRICT, KARNATAKA PRELIMINARY FEASIBILITY REPORT BANGALORE, JULY 1995 Executive Summary The peninsular rivers development Component of the National Perspective envisages interalia diversion of surplus waters of west Flowing Rivers of Kerala and Karnataka to drought hit regions on the eastern side of the western Ghats. In pursuance to this, the present proposal of the Bedti-Varada link is aimed at diverting 242 mm of surplus waters of Bedti basin to water short Tungabhadra sub-basin to be utilised under Tungabhadra Project command. The proposal comprises two dams viz., Pattanadahalla on Pattanadahalla stream and Shalamalahalla on Shalamalahalla stream reservoirs are proposed to be connected by an 8.5 km long conveyance system including 2.2 km long tunnel. The water diverted from pattanadahalla reservoir will be let into a stream at the exit of the conveyance system. Leading to Shalamalahalla reservoir. The combined surpluses of Pattanadahalla and Shalamalahalla are proposed to be diverted from Shalamalahalla reservoir and let into a stream leading to Varada River at the end of 14.83 km long conveyance system which includes 6.8 km long tunnel. The diverted water will be lifted by 123.7 m in three stages before letting into Varada River. The requirement of power for lifting the water works out to 61.10 MW. The annual irrigation proposed under the link is 60,200 ha under left bank canal command of Tungabhadra irrigation project in the drought prone Raichur district of Karnataka. -

At a Glance KARNATAKA BIODIVERSITY BOARD

GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA “BIODIVERSITY OF KARNATAKA” At a Glance Lion fish KARNATAKA BIODIVERSITY BOARD (Forest, Ecology and Environment Department)) Dr. R.C.Prajapati, I.F.S APCCF & Member Secretary IODIVE B RS A IT K Y A T B A O N A R R D A K Ground Floor, “Vanavikas”, 18th Cross, Malleshwaram, Bangalore-560 003 Ph : 080- 23448783, Fax : 080-23440535 E-mail : [email protected] Website :www.kbb.kar.nic.in 2010 - 1 - INDEX Sl No Contents Page No 1 Biodiversity of Karnataka ………Introduction 1 2 Coastal Zone…………………………………….. 2 3 Mangroves in Karnataka……………………….. 3 4 The Western Ghats……………………………… 4 5 Highlights……………………………………….. 6 6 Wildlife of Karnataka…………………………… 7 7 The Eastern Plains Biodiversity……………….. 10 8 Fishes – Biodiversity……………………………. 10 9 Freshwater fishes……………………………….. 12 10 Marine fishes of Karnataka……………………. 12 11 Threatened fishes of Karnataka………………. 13 12 Medicinal Plants Biodiversity……………….. 15 13 Birds Biodiversity……………………………… 20 14 Orchids………………………………………….. 22 15 Butterflies………………………………….……. 25 16 Current status and threat to Biodiversity……. 29 17 Impacts of Pollutants…………………………… 31 18 Biodiversity …………………….… Goals 33 19 Horticulture Biodiversity………………….……. 34 20 Agro Biodiversity……………………………….. 47 21 Domestic Animal Diversity………………..……. 60 22 Coral reef Ecosystem ………………………..….. 66 23 Agro Biodiversity of Karnataka…………..……. 73 - 2 - BIODIVERSITY OF KARNATAKA Introduction Karnataka, one of the Southern states of India has 3.83 Million ha of recorded forest area which is around 20 percent of its geographical area. Karnataka is endowed with most magnificent forests in the country ranging from majestic evergreen forests of the Western Ghats to the scrub jungles of the plains. The Western Ghats of Karnataka are one of the 25 global priority hotspots for conservation and one of the two on the Indian subcontinent.