Separating Myth from Fact What Are Racial Differences in Health?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

ANGELA M. ODOMS-YOUNG UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO, DEPARTMENT OF KINESIOLOGY AND NUTRITION 1919 W. TAYLOR (MC 517), CHICAGO, IL 60612 PHONE: 312-413-0797 FAX: 312-413-0319 EMAIL: [email protected] OR [email protected] DECEMBER 2016 EDUCATION 1999 Ph.D. Major: Community Nutrition; Minors: Program Evaluation/Planning and Toxicology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. Dissertation: The Role of Religion in the Food Choice and Dietary Practices of African-American Muslim Women: The importance of Social and Cultural Context. 1994 M.S. Major: Human Nutrition, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. 1990 B.S. Major: Foods and Nutrition, University of Illinois-Champaign/Urbana, Champaign, IL. POSTGRADUATE TRAINING 2001 – 2003 Postdoctoral Fellowship, Family Research Consortium (FRC) III. Focus Area: Family Processes and Child/Adolescent Mental Health in Diverse Populations. Pennsylvania State University/University of Illinois-Urbana/Champaign. Funded by NIH-National Institute of Mental Health. 1999 – 2000 Postdoctoral Fellowship, Kellogg Community Health Scholars Program. Focus Area: Community-Based Participatory Research. University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI. POSITIONS AND EMPLOYMENT 2015-present Associate Director of Nutrition, Office of Community Engagement and Neighborhood Health Partnerships. University of Illinois Hospital and Health Sciences System. 2014-present Associate Professor, Kinesiology and Nutrition, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL. 2008 – 2014 Assistant Professor, Kinesiology and Nutrition, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL. 2007-present Associate Member, Chicago Diabetes Research and Training Center, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. 2003-2008 Assistant Professor, Public Health and Health Education, College of Nursing and Health Studies, Northern Illinois University, Dekalb, IL. -

CONCEPTUALIZING RACIAL DISPARITIES in HEALTH Advancement of a Socio-Psychobiological Approach

CONCEPTUALIZING RACIAL DISPARITIES IN HEALTH Advancement of a Socio-Psychobiological Approach David H. Chae Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University Amani M. Nuru-Jeter School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley Karen D. Lincoln School of Social Work, University of Southern California Darlene D. Francis School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley Abstract Although racial disparities in health have been documented both historically and in more contemporary contexts, the frameworks used to explain these patterns have varied, ranging from earlier theories regarding innate racial differences in biological vulnerability, to more recent theories focusing on the impact of social inequalities. However, despite increasing evidence for the lack of a genetic definition of race, biological explanations for the association between race and health continue in public health and medical discourse. Indeed, there is considerable debate between those adopting a “social determinants” perspective of race and health and those focusing on more individual-level psychological, behavioral, and biologic risk factors. While there are a number of scientifically plausible and evolving reasons for the association between race and health, ranging from broader social forces to factors at the cellular level, in this essay we argue for the need for more transdisciplinary approaches that specify determinants at multiple ecological levels of analysis. We posit that contrasting ways of examining race and health are not necessarily incompatible, and that more productive discussions should explicitly differentiate between determinants of individual health from those of population health; and between inquiries addressing racial patterns in health from those seeking to explain racial disparities in health. Specifically, we advance a socio-psychobiological framework, which is both historically grounded and evidence-based. -

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN HEALTH CARE, UPDATED 2010 American College of Physicians A Position Paper 2010 Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care A Summary of a Position Paper Approved by the ACP Board of Regents, April 2010 What Are the Sources of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care? The Institute of Medicine defines disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.” Racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive poorer quality care compared with nonminorities, even when access-related factors, such as insurance status and income, are controlled. The sources of racial and ethnic health care disparities include differences in geography, lack of access to adequate health coverage, communication difficulties between patient and provider, cultural barriers, provider stereotyping, and lack of access to providers. In addition, disparities in the health care system contribute to the overall disparities in health status that affect racial and ethnic minorities. Why is it Important to Correct These Disparities? The problem of racial and ethnic health care disparities is highlighted in various statistics: • Minorities have less access to health care than whites. The level of uninsurance for Hispanics is 34% compared with 13% among whites. • Native Americans and Native Alaskans more often lack prenatal care in the first trimester. • Nationally, minority women are more likely to avoid a doctor’s visit due to cost. • Racial and ethnic minority Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with dementia are 30% less likely than whites to use antidementia medications. -

Minutes of the January 25, 2010, Meeting of the Board of Regents

MINUTES OF THE JANUARY 25, 2010, MEETING OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS ATTENDANCE This scheduled meeting of the Board of Regents was held on Monday, January 25, 2010, in the Regents’ Room of the Smithsonian Institution Castle. The meeting included morning, afternoon, and executive sessions. Board Chair Patricia Q. Stonesifer called the meeting to order at 8:31 a.m. Also present were: The Chief Justice 1 Sam Johnson 4 John W. McCarter Jr. Christopher J. Dodd Shirley Ann Jackson David M. Rubenstein France Córdova 2 Robert P. Kogod Roger W. Sant Phillip Frost 3 Doris Matsui Alan G. Spoon 1 Paul Neely, Smithsonian National Board Chair David Silfen, Regents’ Investment Committee Chair 2 Vice President Joseph R. Biden, Senators Thad Cochran and Patrick J. Leahy, and Representative Xavier Becerra were unable to attend the meeting. Also present were: G. Wayne Clough, Secretary John Yahner, Speechwriter to the Secretary Patricia L. Bartlett, Chief of Staff to the Jeffrey P. Minear, Counselor to the Chief Justice Secretary T.A. Hawks, Assistant to Senator Cochran Amy Chen, Chief Investment Officer Colin McGinnis, Assistant to Senator Dodd Virginia B. Clark, Director of External Affairs Kevin McDonald, Assistant to Senator Leahy Barbara Feininger, Senior Writer‐Editor for the Melody Gonzales, Assistant to Congressman Office of the Regents Becerra Grace L. Jaeger, Program Officer for the Office David Heil, Assistant to Congressman Johnson of the Regents Julie Eddy, Assistant to Congresswoman Matsui Richard Kurin, Under Secretary for History, Francisco Dallmeier, Head of the National Art, and Culture Zoological Park’s Center for Conservation John K. -

Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health

COUNTY HEALTH RANKINGS WORKING PAPER DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES FOR ASSIGNING WEIGHTS TO DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH Bridget C. Booske Jessica K. Athens David A. Kindig Hyojun Park Patrick L. Remington FEBRUARY 2010 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................................................................... 4 Weighting Schemes Used by Other Rankings ............................................................................................... 5 Analytic Approach ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Pragmatic Approach .......................................................................................................................................... 8 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix 1: Weighting in Other Rankings .................................................................................................. 11 Appendix 2: Analysis of 2010 County Health Rankings Dataset ............................................................ -

Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research

PU40CH07_Williams ARjats.cls February 25, 2019 11:37 Annual Review of Public Health Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research David R. Williams,1,2,3 Jourdyn A. Lawrence,1 and Brigette A. Davis1 1Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA; email: [email protected] 2Department of African and African American Studies and Department of Sociology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-3654, USA 3Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, University of Cape Town,Cape Town, South Africa Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019. 40:105–25 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on race, ethnicity, racism, racial discrimination, racial inequities January 2, 2019 The Annual Review of Public Health is online at Abstract Access provided by Harvard University on 04/12/19. For personal use only. publhealth.annualreviews.org In recent decades, there has been remarkable growth in scientific re- https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth- Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019.40:105-125. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org search examining the multiple ways in which racism can adversely affect 040218-043750 health. This interest has been driven in part by the striking persistence Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. of racial/ethnic inequities in health and the empirical evidence that indi- All rights reserved cates that socioeconomic factors alone do not account for racial/ethnic in- equities in health. Racism is considered a fundamental cause of adverse health outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities and racial/ethnic inequities in health. This article provides an overview of the evidence linking the primary domains of racism—structural racism, cultural racism, and individual-level discrimination—to mental and physical health outcomes. -

What the Public Thinks About Menatl Health and Mental Illness

What the Public Thinks about Mental Health and ~entaleI1lness A paper presented by Shirley A. Star, Senior Study Director National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago to the Annual Meeting The National Association for Mental Health, Inc. November 19, 1952 For the past two and a half years, the National Opinion Research Center has been engaged upon a pioneering study of the-American public's thinking in the field of mental health, under the joint sponsorship of the National Association for Mental Health and the National Institute of Mental Health, It is a vast and ambitious project, and I'm afraid that the title which has been assigned to my remarks about .the study is going to prove to be misleading in at least two ways. In the first place, and this must be obvious, both the title given me and the scope of the study cover Ear more ground than I could possibly present in the course of one afternoon. About all I can do today is hit a few of the high spots in public thinking and emphasize beforehand that the study aims to be inclusive. You can pretty well assume that it contains some information on just about any question in the area you might raise, even though I don't refer to many of them. So, as they say in the more enterprising shops--"If you don't see what you want, ask for it," In the second place, and this is more serious, I am in the em- barrassing position of having to stand here this afternoon and honestly- -2- admit that I don1t -know what the public thinks as yet. -

Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 Credit Hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas

University of Florida College of Public Health & Health Professions Syllabus PHC 6521: Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 credit hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas Instructor Name: Dr. von Castel Room Number: FSHN 227 Phone Number: 352 Email Address: [email protected] *****PLEASE USE THIS NOT CANVAS Office Hours: by appointment via phone,conferences (in canvas) or Lync(Microsoft) Preferred Course Communications: email through ufl.edu Prerequisites None PURPOSE AND OUTCOME Public health nutrition involves the promotion of health through nutrition and the prevention of nutrition related disease in a population. It focuses on improving the food choices, dietary intake, and nutritional status at the community, regional, or national level. The public health nutrition professional works to assess nutritional problems and needs by considering environmental causes, identifying intervention points, developing policies and programs to intervene at those points, implementing the policies or programs, and evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention. Course Overview This course will provide an introduction to Public Health Nutrition and the role of the Public Health Nutrition professional. Emphasis will be on definition, identification and prevention of nutrition related disease, as well as improving health of a population by improving nutrition. Malnutrition will be discussed on a societal, economic, and environmental level. It will include the basics of nutritional biochemistry as it relates to malnutrition of a community and targeted intervention. Finally, it will review existing programs and policies, including strengths, weaknesses and areas for modification or new interventions. Relation to Program Outcomes MPH Competencies covered 1. Monitor health status to identify and solve community health problems 2. -

Core Principles to Reframe Mental and Behavioral Health Policy 2

Getty Images / Maskot Core Principles to Reframe Mental and Behavioral Health Policy January 2021 Historic and modern-day policies rooted in discrimination and oppression have created and widened harmful inequities impacting many communities of color. Effectively and equitably addressing mental health requires intervening at systemic and policy levels to dismantle the structures that produce negative outcomes like generational poverty, intergenerational and cultural trauma, racism, sexism, and ableism. Changing social, economic, and physical environments alongside key mental and behavioral health supports through immediate relief and longer-term fixes impact individual and community mental health and wellbeing. An individual’s mental health is impacted by and informs nearly every aspect of their life, identity, and community. CLASP looks at how one’s social, economic, and physical environment impact individual and community views of mental health and wellbeing. To improve mental health outcomes, we must think about an individual and family’s economic security, family support, and their community’s built environment. CLASP recognizes the influence of intergenerational and cultural trauma on communities and believes that all mental and behavioral health practices should be trauma-informed and healing- centered. Policymakers must significantly reform and reimagine systems that support the wellbeing of people with low incomes. This includes, but is not exclusive to: • Universal health coverage, as noted in our health care principles; • Recognizing -

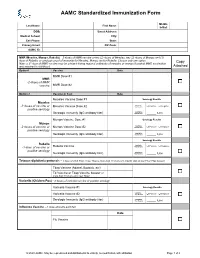

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia

WHO/SDE/HDE/HHR/01.2 • Original: English • Distribution: General WHO’s Contribution to the WorldWorld ConferenceConference AgainstAgainst Racism,Racism, RacialRacial “Vulnerable and marginalized groups in society bear an undue proportion of health problems. Many health disparities are rooted in fundamental social structural inequalities, which are inextricably related to racism and other forms of discrimination Discrimination,Discrimination, in society... Overt or implicit discrimination violates one of the fundamental principles of human rights and often lies at the root of poor health status.” XenophobiaXenophobia The World Health Organization’s contribution to the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance urges the Conference to consider the and Related link between racial discrimination and health, noting in and Related particular the need for further research to be conducted to explore the linkages between health outcomes and racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance. IntoleranceIntolerance Health and freedom from discrimination Health & Human Rights Publication Series–Issue No. 2 For more information, please contact: Helena Nygren-Krug Health and Human Rights Globalization, Cross-sectoral Policies and Human Rights Department of Health and Development World Health Organization Health & Human Rights 20, avenue Appia – 1211 Geneva 27 – Switzerland Publication Series Tel. (41) 22 791 2523 – Fax: (41) 22 791 4726 E-mail: [email protected] Issue No. 2, August 2001 World Health Organization Health and freedom from discrimination This document was produced by the World Health Organization: Department of Health and Development, Sustainable Development and Healthy Environments Cluster, WHO Headquarters, Geneva, together with the Public Policy and Health Program, Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), WHO Regional Office for the Americas, Washington, D.C. -

Roger Dunsmore Came to the University of Montana in 1963 As a Freshman Composition Instructor in the English Department

January 30 Introduction to the Series Roger Dunsmore Bio: Roger Dunsmore came to the University of Montana in 1963 as a freshman composition instructor in the English Department. In 1964 he also began to teach half- time in the Humanities Program. He taught his first course in American Indian Literature, Indian Autobiographies, in 1969. In 1971 he was an originating member of the faculty group that formed the Round River Experiment in Environmental Education (1971- 74) and has taught in UM’s Wilderness and Civilization Program since 1976. He received his MFA in Creative Writing (poetry) in 1971 and his first volume of poetry.On The Road To Sleeping ChildHotsprings was published that same year. (Revised edition, 1977.) Lazslo Toth, a documentary poem on the smashing of Michelangelo’s Pieta was published in 1979. His second full length volume of poems,Bloodhouse, 1987, was selected by the Yellowstone Art Center, Billings, MX for their Regional Writer’s Project.. The title poem of his chapbook.The Sharp-Shinned Hawk, 1987, was nominated by the Koyukon writer, Mary TallMountain for a Pushcat Prize. He retired from full-time teaching after twenty-five years, in 1988, but continues at UM under a one- third time retiree option. During the 1988-89 academic year he was Humanities Scholar in Residence for the Arizona Humanities Council, training teachers at a large Indian high school on the Navajo Reservation. A chapbook of his reading at the International Wildlife Film Festival, The Bear Remembers, was published in 1990. Spring semester, 1991, (and again in the fall semester, 1997) he taught modern American Literature as UM’s Exchange Fellow with Shanghai International Studies University in mainland China.