Core Principles to Reframe Mental and Behavioral Health Policy 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN HEALTH CARE, UPDATED 2010 American College of Physicians A Position Paper 2010 Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care A Summary of a Position Paper Approved by the ACP Board of Regents, April 2010 What Are the Sources of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care? The Institute of Medicine defines disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.” Racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive poorer quality care compared with nonminorities, even when access-related factors, such as insurance status and income, are controlled. The sources of racial and ethnic health care disparities include differences in geography, lack of access to adequate health coverage, communication difficulties between patient and provider, cultural barriers, provider stereotyping, and lack of access to providers. In addition, disparities in the health care system contribute to the overall disparities in health status that affect racial and ethnic minorities. Why is it Important to Correct These Disparities? The problem of racial and ethnic health care disparities is highlighted in various statistics: • Minorities have less access to health care than whites. The level of uninsurance for Hispanics is 34% compared with 13% among whites. • Native Americans and Native Alaskans more often lack prenatal care in the first trimester. • Nationally, minority women are more likely to avoid a doctor’s visit due to cost. • Racial and ethnic minority Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with dementia are 30% less likely than whites to use antidementia medications. -

Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health

COUNTY HEALTH RANKINGS WORKING PAPER DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES FOR ASSIGNING WEIGHTS TO DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH Bridget C. Booske Jessica K. Athens David A. Kindig Hyojun Park Patrick L. Remington FEBRUARY 2010 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................................................................... 4 Weighting Schemes Used by Other Rankings ............................................................................................... 5 Analytic Approach ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Pragmatic Approach .......................................................................................................................................... 8 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix 1: Weighting in Other Rankings .................................................................................................. 11 Appendix 2: Analysis of 2010 County Health Rankings Dataset ............................................................ -

What the Public Thinks About Menatl Health and Mental Illness

What the Public Thinks about Mental Health and ~entaleI1lness A paper presented by Shirley A. Star, Senior Study Director National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago to the Annual Meeting The National Association for Mental Health, Inc. November 19, 1952 For the past two and a half years, the National Opinion Research Center has been engaged upon a pioneering study of the-American public's thinking in the field of mental health, under the joint sponsorship of the National Association for Mental Health and the National Institute of Mental Health, It is a vast and ambitious project, and I'm afraid that the title which has been assigned to my remarks about .the study is going to prove to be misleading in at least two ways. In the first place, and this must be obvious, both the title given me and the scope of the study cover Ear more ground than I could possibly present in the course of one afternoon. About all I can do today is hit a few of the high spots in public thinking and emphasize beforehand that the study aims to be inclusive. You can pretty well assume that it contains some information on just about any question in the area you might raise, even though I don't refer to many of them. So, as they say in the more enterprising shops--"If you don't see what you want, ask for it," In the second place, and this is more serious, I am in the em- barrassing position of having to stand here this afternoon and honestly- -2- admit that I don1t -know what the public thinks as yet. -

Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 Credit Hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas

University of Florida College of Public Health & Health Professions Syllabus PHC 6521: Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 credit hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas Instructor Name: Dr. von Castel Room Number: FSHN 227 Phone Number: 352 Email Address: [email protected] *****PLEASE USE THIS NOT CANVAS Office Hours: by appointment via phone,conferences (in canvas) or Lync(Microsoft) Preferred Course Communications: email through ufl.edu Prerequisites None PURPOSE AND OUTCOME Public health nutrition involves the promotion of health through nutrition and the prevention of nutrition related disease in a population. It focuses on improving the food choices, dietary intake, and nutritional status at the community, regional, or national level. The public health nutrition professional works to assess nutritional problems and needs by considering environmental causes, identifying intervention points, developing policies and programs to intervene at those points, implementing the policies or programs, and evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention. Course Overview This course will provide an introduction to Public Health Nutrition and the role of the Public Health Nutrition professional. Emphasis will be on definition, identification and prevention of nutrition related disease, as well as improving health of a population by improving nutrition. Malnutrition will be discussed on a societal, economic, and environmental level. It will include the basics of nutritional biochemistry as it relates to malnutrition of a community and targeted intervention. Finally, it will review existing programs and policies, including strengths, weaknesses and areas for modification or new interventions. Relation to Program Outcomes MPH Competencies covered 1. Monitor health status to identify and solve community health problems 2. -

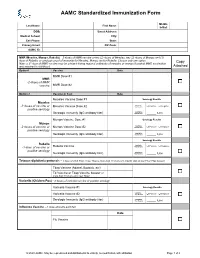

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

COVID-19 Vaccination Requirement (Proclamation 21-14.1) for Health Care Providers, Workers and Settings

Updated September 2021 DOH 505-160 COVID-19 Vaccination Requirement (Proclamation 21-14.1) for health care providers, workers and settings Link to proclamation: 21-14.1 - COVID-19 Vax Washington General Proclamation Questions What does Proclamation 21-14.1 do? Proclamation 21-14.1, issued by Governor Inslee on August 20, 2021, made numerous changes to Proclamation 21-14, issued by Governor Inslee on August 9, 2021, but left the same core requirements in place. As before, the proclamation requires health care providers, defined broadly to include not only licensed health care providers but also all employees, contractors, and volunteers who work in a health care setting, to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 by October 18, 2021. It also requires operators of health care settings to verify the vaccination status of: a) Every employee, volunteer, and contractor who works in the health care setting, whether or not they are licensed or providing health care services, and b) Every employee, volunteer, and contractor who provides health care services for the health care setting operator. On what legal grounds can this be imposed? In response to the emerging COVID-19 threat, Governor Inslee declared a state of emergency on February 29, 2020, using his broad emergency authority under chapter 43.06 RCW. More specifically, under RCW 43.06.220, after a state of emergency has been declared, the governor may prohibit any activity that they believe should be prohibited to help preserve and maintain life, health, property or the public peace. Under an emergency such as this, the governor’s paramount duty is to protect the health and safety of our communities. -

2021-22 School Year New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance1

2021-22 School Year New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance1 NOTES: Children in a prekindergarten setting should be age-appropriately immunized. The number of doses depends on the schedule recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Intervals between doses of vaccine should be in accordance with the ACIP-recommended immunization schedule for persons 0 through 18 years of age. Doses received before the minimum age or intervals are not valid and do not count toward the number of doses listed below. See footnotes for specific information foreach vaccine. Children who are enrolling in grade-less classes should meet the immunization requirements of the grades for which they are age equivalent. Dose requirements MUST be read with the footnotes of this schedule Prekindergarten Kindergarten and Grades Grades Grade Vaccines (Day Care, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 12 Head Start, and 11 Nursery or Pre-k) Diphtheria and Tetanus 5 doses toxoid-containing vaccine or 4 doses and Pertussis vaccine 4 doses if the 4th dose was received 3 doses (DTaP/DTP/Tdap/Td)2 at 4 years or older or 3 doses if 7 years or older and the series was started at 1 year or older Tetanus and Diphtheria toxoid-containing vaccine Not applicable 1 dose and Pertussis vaccine adolescent booster (Tdap)3 Polio vaccine (IPV/OPV)4 4 doses 3 doses or 3 doses if the 3rd dose was received at 4 years or older Measles, Mumps and 1 dose 2 doses Rubella vaccine (MMR)5 Hepatitis B vaccine6 3 doses 3 doses or 2 doses of adult hepatitis B vaccine (Recombivax) for children who received the doses at least 4 months apart between the ages of 11 through 15 years Varicella (Chickenpox) 1 dose 2 doses vaccine7 Meningococcal conjugate Grades 2 doses vaccine (MenACWY)8 7, 8, 9, 10 or 1 dose Not applicable and 11: if the dose 1 dose was received at 16 years or older Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine 1 to 4 doses Not applicable (Hib)9 Pneumococcal Conjugate 1 to 4 doses Not applicable vaccine (PCV)10 Department of Health 1. -

Public Health Nutrition Job Outlook

MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH – PUBLIC HEALTH NUTRITION The above charts pertain to recent graduates between 2008 – 2011 (Career Survey Data) JOB OUTLOOK Public Health Nutrition: Overall, approximately 60 percent of graduates work in public health agencies (e.g., local and state health departments, and national public health agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), 20 percent in educational institutions or the USDA Cooperative Extension Service, and the remainder in health promotion and education programs in health care organizations and private industry. Other graduates are public relations and media consultants, internship directors, or in private practice/consulting. Some graduates of the Public Health Nutrition MPH program choose to continue their graduate studies by pursuing a PhD or other professional degrees. The University of Minnesota offers two options for PhD programs in nutrition. The Interdisciplinary Nutrition Graduate Program offers doctoral students the opportunity to focus their studies in public health nutrition. Similarly, students in the Epidemiology PhD Program have the opportunity to focus on nutritional epidemiology. Several graduates of the Public Health Nutrition MPH Program are currently pursuing doctoral degrees in these programs. Career Prospects: The MPH degree in Public Health Nutrition prepares graduates for a wide variety of positions in national, state and local public health agencies; non-profit health agencies; international non-governmental organizations; and community service organizations. Individuals who also obtain or hold the Registered Dietitian credential are also prepared to obtain positions in health care settings such as hospitals and clinics. Professionals with training in public health nutrition, regardless of their place of employment, are involved in assessing individuals, communities and populations; developing, implementing and evaluating nutrition interventions; and monitoring the health of individuals, communities and populations. -

Race, Health, and COVID-19: the Views and Experiences of Black Americans

October 2020 Race, Health, and COVID-19: The Views and Experiences of Black Americans Key Findings from the KFF/Undefeated Survey on Race and Health Prepared by: Liz Hamel, Lunna Lopes, Cailey Muñana, Samantha Artiga, and Mollyann Brodie KFF Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 4 The Big Picture: Being Black in America Today ........................................................................................... 6 The Disproportionate Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic .......................................................................... 11 Views Of A Potential COVID-19 Vaccine .................................................................................................... 16 Trust And Experiences In The Health Care System ................................................................................... 22 Trust of Providers and Hospitals ............................................................................................................. 22 Perceptions of Unfair Treatment in Health Care ..................................................................................... 24 Experiences With and Access to Health Care Providers ........................................................................ 26 Conclusion.................................................................................................................................................. -

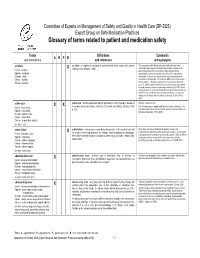

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

Behavioral Health Integration

SAMHSA – Behavioral Health Integration SAMHSA is working closely with its federal partners to ensure that behavioral health is consistently viewed and incorporated within the context of health promotion and health care delivery and financing. SAMHSA’s strategic initiative in this area will require the ongoing commitment of HHS, specifically CMS, HRSA, CDC, ACF and ASPE, to advance efforts to recognize behavioral health as essential to health, improve access to services, develop financing mechanisms to support positive client outcomes, and address costs. Introduction The term “behavioral health” in this context means the promotion of mental health, resilience and wellbeing; the treatment of mental and substance use disorders; and the support of those who experience and/or are in recovery from these conditions, along with their families and communities. Behavioral health conditions and the behavioral health field have historically been financed, authorized, structured, researched, and regulated differently than other health conditions. As we learn more about the physical impacts of traumatic experiences and behavioral health conditions, and the behavioral impacts of physical health conditions, we will need to view behavioral health as we do any other health issue. As a consequence, systems, financing, laws, and structures will have to change to incorporate and respond appropriately to these new understandings. The impact of untreated behavioral health conditions on individuals’ lives and the cost of health care delivery in the United States is staggering. Persons with any mental illness are more likely to have chronic conditions such as high blood pressure, asthma, diabetes, heart disease and stroke than those without mental illness. And, those individuals are more likely to use hospitalization and emergency room treatment. -

Introduction to Public Health Instructor Name Title Organization

Public Health 101 Series Introduction to Public Health Instructor name Title Organization Note: This slide set is in the public domain and may be customized as needed by the user for informational or educational purposes. Permission from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is not required, but citation of the source is appreciated. Course Topics Introduction to Public Health 1. Public Health Definition and Key Terms 2. History of Public Health 3. A Public Health Approach 4. Core Functions and Essential Services of Public Health 5. Stakeholder Roles in Public Health 6. Determining and Influencing the Public’s Health 2 Learning Objectives After this course, you will be able to • describe the purpose of public health • define key terms used in public health • identify prominent events in the history of public health • recognize the core public health functions and services • describe the role of different stakeholders in the field of public health • list some determinants of health • recognize how individual determinants of health affect population health 3 Topic 1 Public Health Definition and Key Terms 4 Public Health Defined “The science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private communities, and individuals.” —CEA Winslow Photo: IF Fisher and EL Fisk Winslow CEA. The untilled field of public health. Mod Med 1920;2:183–91. 5 The Mission of Public Health “Fulfilling society’s interest in assuring conditions in which people can be healthy.” —Institute of Medicine “Public health aims to provide maximum benefit for the largest number of people.” —World Health Organization 6 Public Health Key Terms clinical care: prevention, treatment, and management of illness and the preservation of mental and physical well-being through the services offered by medical and allied health professions; also known as health care.