A Closer Look at Air Pollution in Houston: Identifying Priority Health Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Updated 2010

RACIAL AND ETHNIC DISPARITIES IN HEALTH CARE, UPDATED 2010 American College of Physicians A Position Paper 2010 Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care A Summary of a Position Paper Approved by the ACP Board of Regents, April 2010 What Are the Sources of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care? The Institute of Medicine defines disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.” Racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive poorer quality care compared with nonminorities, even when access-related factors, such as insurance status and income, are controlled. The sources of racial and ethnic health care disparities include differences in geography, lack of access to adequate health coverage, communication difficulties between patient and provider, cultural barriers, provider stereotyping, and lack of access to providers. In addition, disparities in the health care system contribute to the overall disparities in health status that affect racial and ethnic minorities. Why is it Important to Correct These Disparities? The problem of racial and ethnic health care disparities is highlighted in various statistics: • Minorities have less access to health care than whites. The level of uninsurance for Hispanics is 34% compared with 13% among whites. • Native Americans and Native Alaskans more often lack prenatal care in the first trimester. • Nationally, minority women are more likely to avoid a doctor’s visit due to cost. • Racial and ethnic minority Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with dementia are 30% less likely than whites to use antidementia medications. -

Equity Review

CITY OF HOUSTON CIVIC ART COLLECTION EQUITY REVIEW EQUITY REVIEW | 2020 2020 | 1 Cover Image: Hannah Stewart, Atropos Key Location: Hermann Park, District D 2 | CITY OF HOUSTON | CIVIC ART COLLECTION Civic Art Collection Equity Review 2020 by the City of Houston Mayor’s Office of Cultural Affairs September 30, 2020 Written By Deborah McNulty, Director Theresa Escobedo, Project Lead Monique Mogilka, Community Liaison Data Collection and Analysis Monique Mogilka, Community Liaison Arif Fusilier, Summer Intern Houston Arts Alliance Civic Art + Design Department Edited By Necole Irvin Photography By Alex Barber Special thanks to the City of Houston’s Hire Houston Youth program. EQUITY REVIEW | 2020 | 3 Luis Jiménez, Vaquero Location: Moody Park, District H 4 | CITY OF HOUSTON | CIVIC ART COLLECTION CONTENTS Introduction..............................................................................p. 7 Key Findings..............................................................................p. 8 Methodology.............................................................................p. 9 Race/Ethnicity Definitions.......................................p. 10 City Departments Identified...................................p. 10 Houston and United States Demographics.........................p. 12 Artists Represented by Race/Ethnicity .................................p. 15 Artists Represented by Gender ..............................................p. 18 Female BIPOC Artist Representation....................................p. 19 Acquisition Costs.....................................................................p.22 -

Artist-Planner Collaborations Lessons Learned from the Arts and Culture Ecosystems of Three Sun Belt Cities for a New Model of Inclusive Planning

Artist-Planner Collaborations Lessons learned from the arts and culture ecosystems of three Sun Belt cities for a new model of inclusive planning. Photo by Mike Petrucci on Unsplash Building Better Cities Building Better Lives June 2019 Report contributors: Grant Patterson and Leah Binkovitz Rice University Kinder Institute for Urban Research 6100 Main Street, MS-208, Houston, TX 77005 For more information, contact [email protected] or 713-348-4132. Copyright © 2019 by Rice Kinder Institute for Urban Research All rights reserved. Recommended citation: Patterson, Grant and Leah Binkovitz. Artist-Planner Collaborations: Lessons learned from the arts and culture ecosystems of three Sun Belt cities for a new model of inclusive planning. Report. Kinder Institute for Urban Research, Rice University. Houston, TX: Kinder Institute for Urban Research, 2019. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 Introduction 6 Case Studies 8 Emerging Themes 16 Arts and Culture within Complete Communities 18 Employing Artist-Planner Collaboration in Complete Communities 20 Conclusion 22 Citations Artist-Planner Collaborations Lessons learned from the arts and culture ecosystems of three Sun Belt cities for a new model of inclusive planning. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Executive Summary ibrant arts and culture offerings attract visitors from around the region and Vbeyond, provide gathering spaces and encourage social interaction and collective action. Furthermore, they facilitate the celebration of unique places through historic preservation, public art, cultural festivals and other community-rooted creative activities. In Houston and other cities, cultural planners are working to proactively and comprehensively plan for the impact that the arts and culture can have on their cities and neighborhoods, strategize how to promote and expand those impacts and engage with diverse stakeholders to envision the future of arts and culture moving forward. -

Different Perspectives for Assigning Weights to Determinants of Health

COUNTY HEALTH RANKINGS WORKING PAPER DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVES FOR ASSIGNING WEIGHTS TO DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH Bridget C. Booske Jessica K. Athens David A. Kindig Hyojun Park Patrick L. Remington FEBRUARY 2010 Table of Contents Summary .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Historical Perspective ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Review of the Literature ................................................................................................................................... 4 Weighting Schemes Used by Other Rankings ............................................................................................... 5 Analytic Approach ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Pragmatic Approach .......................................................................................................................................... 8 References ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 Appendix 1: Weighting in Other Rankings .................................................................................................. 11 Appendix 2: Analysis of 2010 County Health Rankings Dataset ............................................................ -

What the Public Thinks About Menatl Health and Mental Illness

What the Public Thinks about Mental Health and ~entaleI1lness A paper presented by Shirley A. Star, Senior Study Director National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago to the Annual Meeting The National Association for Mental Health, Inc. November 19, 1952 For the past two and a half years, the National Opinion Research Center has been engaged upon a pioneering study of the-American public's thinking in the field of mental health, under the joint sponsorship of the National Association for Mental Health and the National Institute of Mental Health, It is a vast and ambitious project, and I'm afraid that the title which has been assigned to my remarks about .the study is going to prove to be misleading in at least two ways. In the first place, and this must be obvious, both the title given me and the scope of the study cover Ear more ground than I could possibly present in the course of one afternoon. About all I can do today is hit a few of the high spots in public thinking and emphasize beforehand that the study aims to be inclusive. You can pretty well assume that it contains some information on just about any question in the area you might raise, even though I don't refer to many of them. So, as they say in the more enterprising shops--"If you don't see what you want, ask for it," In the second place, and this is more serious, I am in the em- barrassing position of having to stand here this afternoon and honestly- -2- admit that I don1t -know what the public thinks as yet. -

Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 Credit Hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas

University of Florida College of Public Health & Health Professions Syllabus PHC 6521: Fundamentals of Public Health Nutrition (3 credit hours) Fall: 2018 Delivery Format: E-Learning in Canvas Instructor Name: Dr. von Castel Room Number: FSHN 227 Phone Number: 352 Email Address: [email protected] *****PLEASE USE THIS NOT CANVAS Office Hours: by appointment via phone,conferences (in canvas) or Lync(Microsoft) Preferred Course Communications: email through ufl.edu Prerequisites None PURPOSE AND OUTCOME Public health nutrition involves the promotion of health through nutrition and the prevention of nutrition related disease in a population. It focuses on improving the food choices, dietary intake, and nutritional status at the community, regional, or national level. The public health nutrition professional works to assess nutritional problems and needs by considering environmental causes, identifying intervention points, developing policies and programs to intervene at those points, implementing the policies or programs, and evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention. Course Overview This course will provide an introduction to Public Health Nutrition and the role of the Public Health Nutrition professional. Emphasis will be on definition, identification and prevention of nutrition related disease, as well as improving health of a population by improving nutrition. Malnutrition will be discussed on a societal, economic, and environmental level. It will include the basics of nutritional biochemistry as it relates to malnutrition of a community and targeted intervention. Finally, it will review existing programs and policies, including strengths, weaknesses and areas for modification or new interventions. Relation to Program Outcomes MPH Competencies covered 1. Monitor health status to identify and solve community health problems 2. -

Harrisburg Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone May 2016 Inside Cover Table of Contents

Existing Conditions Harrisburg Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone May 2016 Inside Cover Table of Contents Introduction Housing LOCATION .......................................................... 5 HOUSING STOCK ................................................ 29 EXISTING PL ANS AND STUDIES ............................... 12 HOUSING TYpeS ................................................. 30 Land Use & Mobility AGE ................................................................ 30 EleMENTS OF THE DISTRICT ................................... 13 Crime LAND USE/PROpeRTY CL ASSIFICATION ..................... 13 Economic Indicators ROADWAYS ........................................................ 16 BUSINESS SUMMARY ............................................ 35 TRAFFIC VOLUMES ............................................... 16 RETAIL TRADE .................................................... 38 RAILROAD ......................................................... 17 DAY TIME POPUL ATION .......................................... 40 BIKEWAYS ......................................................... 17 Planned Infrastructure Improvements RAILS TO TRAILS ................................................. 17 CAPITAL IMPROveMENTS ....................................... 45 PARKS & TRAILS ................................................. 21 RebUILD HOUSTON +5 ........................................ 45 REIMAGINE METRO ............................................. 21 Observations People OBSERVATIONS ................................................... 49 -

Core Principles to Reframe Mental and Behavioral Health Policy 2

Getty Images / Maskot Core Principles to Reframe Mental and Behavioral Health Policy January 2021 Historic and modern-day policies rooted in discrimination and oppression have created and widened harmful inequities impacting many communities of color. Effectively and equitably addressing mental health requires intervening at systemic and policy levels to dismantle the structures that produce negative outcomes like generational poverty, intergenerational and cultural trauma, racism, sexism, and ableism. Changing social, economic, and physical environments alongside key mental and behavioral health supports through immediate relief and longer-term fixes impact individual and community mental health and wellbeing. An individual’s mental health is impacted by and informs nearly every aspect of their life, identity, and community. CLASP looks at how one’s social, economic, and physical environment impact individual and community views of mental health and wellbeing. To improve mental health outcomes, we must think about an individual and family’s economic security, family support, and their community’s built environment. CLASP recognizes the influence of intergenerational and cultural trauma on communities and believes that all mental and behavioral health practices should be trauma-informed and healing- centered. Policymakers must significantly reform and reimagine systems that support the wellbeing of people with low incomes. This includes, but is not exclusive to: • Universal health coverage, as noted in our health care principles; • Recognizing -

Texas Municipal Report PHA Debt 2019-0521

Port of Houston Auth Texas Municipal Reports © (General Obligation Debt) Last Revised: 5/21/2019 TMR # 5697 Harris County Page 1 of 12 FINANCIAL STATEMENT Lead Manager: Bank of America Merrill Lynch Co-Manager: Jefferies & Company FINANCIAL STATEMENT (As of December 31, 2018) Co-Manager: RBC Capital Markets Co-Manager: Samuel A. Ramirez & Co., Inc. Net Taxable Assessed Valuation ("A.V."), 2018 $437,676,928,000 Co-Manager: Siebert Brandford Shank & Co. GO Debt payable from Ad Valorem Taxes $593,754,397 Use of Proceeds: Refunding. Less: I&S Fund 44,646,000 ------------------ Refunding Notes: This issue defeased mty(s) 10/1/2010-10/1/2015, 10/01/2017, Net Debt $549,108,397 10/1/2019 of U/L Tax Port Imp Bds Ser 98A @ par. ================== Orig Reoffering Net Debt Per Net Taxable Assessed Valuation - 0.13% Maturity Amount Coupon Price/Yield Net Debt Per Sq mile - $308,834.87 Net Debt Per Capita - $118.01 10/01/2019 3,660,000.00 5.0000% 4.150% -------------------------------------------------$3,660,000.00 Net Taxable Assessed Valuation Per Capita - $94,063.79 Call Option: Non Callable Bureau of Census Pop: 2000 - 3,400,578 Bureau of Census Pop: 2010 - 4,092,459 2017 Estimated Population - 4,652,980 U/L Tax Ref Bds Ser 2010B (NON-AMT) Area: 1,778.00 Sq mile Tax Treatment: Tax Exempt Original Issue Amount $22,930,000.00 PAYMENT RECORD Dated Date: 12/01/2009 Sale Date: 01/14/2010 Delivery Date: 02/17/2010 Never defaulted. Sale Type: Negotiated Record Date: MSRB TAX DATA Bond Form: BE Denomination $5,000 Interest pays Semi-Annually: 10/01, 04/01 Tax Tax Adjusted % Collections Year 1st Coupon Date: 04/01/2010 Year A.V. -

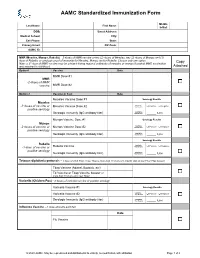

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

COVID-19 Vaccination Requirement (Proclamation 21-14.1) for Health Care Providers, Workers and Settings

Updated September 2021 DOH 505-160 COVID-19 Vaccination Requirement (Proclamation 21-14.1) for health care providers, workers and settings Link to proclamation: 21-14.1 - COVID-19 Vax Washington General Proclamation Questions What does Proclamation 21-14.1 do? Proclamation 21-14.1, issued by Governor Inslee on August 20, 2021, made numerous changes to Proclamation 21-14, issued by Governor Inslee on August 9, 2021, but left the same core requirements in place. As before, the proclamation requires health care providers, defined broadly to include not only licensed health care providers but also all employees, contractors, and volunteers who work in a health care setting, to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 by October 18, 2021. It also requires operators of health care settings to verify the vaccination status of: a) Every employee, volunteer, and contractor who works in the health care setting, whether or not they are licensed or providing health care services, and b) Every employee, volunteer, and contractor who provides health care services for the health care setting operator. On what legal grounds can this be imposed? In response to the emerging COVID-19 threat, Governor Inslee declared a state of emergency on February 29, 2020, using his broad emergency authority under chapter 43.06 RCW. More specifically, under RCW 43.06.220, after a state of emergency has been declared, the governor may prohibit any activity that they believe should be prohibited to help preserve and maintain life, health, property or the public peace. Under an emergency such as this, the governor’s paramount duty is to protect the health and safety of our communities. -

Official Statement Series 2015A 2015B 2015C

OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED JULY 21, 2015 NEW ISSUES - BOOK-ENTRY ONLY RATINGS: Fitch “AAA” S&P “AAA” In the opinion of Bracewell & Giuliani LLP, Bond Counsel, under existing law, (a) interest on the Series 2015A Bonds (as defined below) is excludable from gross income for federal income tax purposes and the Series 2015A Bonds are not “private activity bonds” and (b) (i) interest on the Series 2015B Bonds (as defined below) is excludable from gross income for federal income tax purposes, except with respect to interest on any Series 2015B Bond for any period during which such Series 2015B Bond is held by a person who, within the meaning of Section 147(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, is a “substantial user” or a “related person” to such a “substantial user” of the facilities financed or refinanced with the proceeds of the Series 2015B Bonds, as described under “TAX MATTERS—Tax Exemption – Series 2015 Bonds” herein, and (ii) interest on the Series 2015B Bonds is an item of tax preference that is includable in alternative minimum taxable income for purposes of determining the alternative minimum tax imposed on individuals and corporations. See “TAX MATTERS—Tax Exemption – Series 2015A Bonds” for a discussion of the opinion of Bond Counsel, including a description of alternative minimum tax consequences for corporations, for the Series 2015A Bonds and “TAX MATTERS—Tax Exemption – Series 2015B Bonds” for a discussion of the opinion of Bond Counsel for the Series 2015B Bonds. Interest on the Series 2015C Bonds (as defined below) is not excludable from gross income for federal tax purposes under existing law.