Geologic Setting of Table Mountain Boulder County, Colorado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phase I Avian Risk Assessment

PHASE I AVIAN RISK ASSESSMENT Garden Peninsula Wind Energy Project Delta County, Michigan Report Prepared for: Heritage Sustainable Energy October 2007 Report Prepared by: Paul Kerlinger, Ph.D. John Guarnaccia Curry & Kerlinger, L.L.C. P.O. Box 453 Cape May Point, NJ 08212 (609) 884-2842, fax 884-4569 [email protected] [email protected] Garden Peninsula Wind Energy Project, Delta County, MI Phase I Avian Risk Assessment Garden Peninsula Wind Energy Project Delta County, Michigan Executive Summary Heritage Sustainable Energy is proposing a utility-scale wind-power project of moderate size for the Garden Peninsula on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan in Delta County. This peninsula separates northern Lake Michigan from Big Bay de Noc. The number of wind turbines is as yet undetermined, but a leasehold map provided to Curry & Kerlinger indicates that turbines would be constructed on private lands (i.e., not in the Lake Superior State Forest) in mainly agricultural areas on the western side of the peninsula, and possibly on Little Summer Island. For the purpose of analysis, we are assuming wind turbines with a nameplate capacity of 2.0 MW. The turbine towers would likely be about 78.0 meters (256 feet) tall and have rotors of about 39.0 m (128 feet) long. With the rotor tip in the 12 o’clock position, the wind turbines would reach a maximum height of about 118.0 m (387 feet) above ground level (AGL). When in the 6 o’clock position, rotor tips would be about 38.0 m (125 feet) AGL. However, larger turbines with nameplate capacities (up to 2.5 MW and more) reaching to 152.5 m (500 feet) are may be used. -

Geomorphic Classification of Rivers

9.36 Geomorphic Classification of Rivers JM Buffington, U.S. Forest Service, Boise, ID, USA DR Montgomery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Published by Elsevier Inc. 9.36.1 Introduction 730 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification 730 9.36.3 Types of Channel Classification 731 9.36.3.1 Stream Order 731 9.36.3.2 Process Domains 732 9.36.3.3 Channel Pattern 732 9.36.3.4 Channel–Floodplain Interactions 735 9.36.3.5 Bed Material and Mobility 737 9.36.3.6 Channel Units 739 9.36.3.7 Hierarchical Classifications 739 9.36.3.8 Statistical Classifications 745 9.36.4 Use and Compatibility of Channel Classifications 745 9.36.5 The Rise and Fall of Classifications: Why Are Some Channel Classifications More Used Than Others? 747 9.36.6 Future Needs and Directions 753 9.36.6.1 Standardization and Sample Size 753 9.36.6.2 Remote Sensing 754 9.36.7 Conclusion 755 Acknowledgements 756 References 756 Appendix 762 9.36.1 Introduction 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification Over the last several decades, environmental legislation and a A basic tenet in geomorphology is that ‘form implies process.’As growing awareness of historical human disturbance to rivers such, numerous geomorphic classifications have been de- worldwide (Schumm, 1977; Collins et al., 2003; Surian and veloped for landscapes (Davis, 1899), hillslopes (Varnes, 1958), Rinaldi, 2003; Nilsson et al., 2005; Chin, 2006; Walter and and rivers (Section 9.36.3). The form–process paradigm is a Merritts, 2008) have fostered unprecedented collaboration potentially powerful tool for conducting quantitative geo- among scientists, land managers, and stakeholders to better morphic investigations. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

Table 2. Summary of Key Project Metrics for Setback Levee Alternatives

TABLE 2. SUMMARY OF KEY PROJECT METRICS FOR SETBACK LEVEE ALTERNATIVES Existing Metric Units Alt. 1 Alt. 2 Alt. 3 Alt. 4 Conditions CARBON RIVER, LEVEE, AND FLOODPLAIN Reach River Miles River Miles RM 3.0 - 4.5 RM 3.0 - 4.5 RM 3.0 - 4.5 RM 3.0 - 4.5 RM 3.0 - 3.9 Reach Length River Miles 1.5 1.5 1.5 1.5 0.9 New Levee Overall 1.1, plus Miles 1.43 1.61 1.69 1.84 Length 0.3 stub levee New Levee Overall Feet 7600 8500 8900 9700 7400 Length Floodwall Length Feet 0 0 500 0 0 Ties into accredited levee or high ground Yes/No No No No No No upstream? Ties into accredited levee or high ground Yes/No No No No No No downstream? Potential Channel Migration Area (area Acres 0.0 60 122 124 43 between existing levee and setback levee) Reconnected Floodplain Area within Acres 0 45 74 70 23 100-year Inundation Area Reconnected Floodplain Area within Acres 0 34 49 46 20 2-year Inundation Area Carbon River Potential Active Channel Width at RM 3.8 Pinch Point Feet 260 540 540 850 380 (assuming right bank side remains fixed) HABITAT Side channel created Lineal Feet 0.0 3500 3500 3600 600 Existing Metric Units Alt. 1 Alt. 2 Alt. 3 Alt. 4 Conditions 26 multi-log jams and 583 individual Wood added to active Number key logs 700 750 750 300 channel pieces (Per analysis of 2018 aerial photograph) Wood added to Number key Not 200 250 250 100 floodplain pieces measured Wetlands Impacted by Acres 0.0 7 5 5 4 Levee Footprint Floodplain Riparian and Wetland Acres 0.0 45 61 60 25 Establishment or Enhancement VOIGHTS CREEK Voights Creek Reach Length in Same as Reconnected Miles 0.00 0.16 0.57 0.39 existing Floodplain (Setback condition Levee to Existing Levee) Voights Creek Length Same as SR162 to Setback Miles 0.57 0.41 0.0 0.18 existing Levee condition Crossing at New Crossing New Crossing existing at Setback at Setback levee No new Retains Fish passable Levee Levee -- appears to crossing existing crossings replaces replaces meet WDFW required. -

A Geomorphic Classification System

A Geomorphic Classification System U.S.D.A. Forest Service Geomorphology Working Group Haskins, Donald M.1, Correll, Cynthia S.2, Foster, Richard A.3, Chatoian, John M.4, Fincher, James M.5, Strenger, Steven 6, Keys, James E. Jr.7, Maxwell, James R.8 and King, Thomas 9 February 1998 Version 1.4 1 Forest Geologist, Shasta-Trinity National Forests, Pacific Southwest Region, Redding, CA; 2 Soil Scientist, Range Staff, Washington Office, Prineville, OR; 3 Area Soil Scientist, Chatham Area, Tongass National Forest, Alaska Region, Sitka, AK; 4 Regional Geologist, Pacific Southwest Region, San Francisco, CA; 5 Integrated Resource Inventory Program Manager, Alaska Region, Juneau, AK; 6 Supervisory Soil Scientist, Southwest Region, Albuquerque, NM; 7 Interagency Liaison for Washington Office ECOMAP Group, Southern Region, Atlanta, GA; 8 Water Program Leader, Rocky Mountain Region, Golden, CO; and 9 Geology Program Manager, Washington Office, Washington, DC. A Geomorphic Classification System 1 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 5 I. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 6 History of Classification Efforts in the Forest Service ............................................................... 6 History of Development .............................................................................................................. 7 Goals -

The Favorability of Florida's Geology to Sinkhole

Appendix H: Sinkhole Report 2018 State Hazard Mitigation Plan _______________________________________________________________________________________ APPENDIX H: Sinkhole Report _______________________________________________________________________________________ Florida Division of Emergency Management THE FAVORABILITY OF FLORIDA’S GEOLOGY TO SINKHOLE FORMATION Prepared For: The Florida Division of Emergency Management, Mitigation Section Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Florida Geological Survey 3000 Commonwealth Boulevard, Suite 1, Tallahassee, Florida 32303 June 2017 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 Background ................................................................................................................................. 5 Subsidence Incident Report Database ..................................................................................... 6 Purpose and Scope ...................................................................................................................... 7 Sinkhole Development ................................................................................................................ 7 Subsidence Sinkhole Formation .............................................................................................. 8 Collapse Sinkhole -

The Prairie Peninsula (Physiographic Area 31) Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for the Prairie Peninsula (Physiographic Area 31)

Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for The Prairie Peninsula (Physiographic Area 31) Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for The Prairie Peninsula (Physiographic Area 31) Version 1.0 4 February 2000 by Jane A. Fitzgerald, James R. Herkert and Jeffrey D. Brawn Please address comments to: Jane Fitzgerald PIF Midwest Regional Coordinator 8816 Manchester, suite 135 Brentwood, MO 63144 314-918-8505 e-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents: Executive Summary .......................................................1 Preface ................................................................3 Section 1: The planning unit Background .............................................................4 Conservation issues ........................................................4 General conservation opportunities .............................................8 Section 2: Avifaunal analysis General characteristics .....................................................9 Priority species .......................................................... 12 Section 3: Habitats and objectives Habitat-species suites ..................................................... 14 Grasslands ............................................................. 15 Ecology and conservation status ............................................ 15 Bird habitat requirements ................................................. 15 Population objectives and habitat strategies .................................... 20 Grassland conservation opportunities ........................................ -

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography

Table 2. Geographic Areas, and Biography The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 09 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., public libraries (027.4) in Japan (—52 in this table): 027.452; railroad transportation (385) in Brazil (—81 in this table): 385.0981. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 025 from Table 1. When adding to a number from the schedules, always insert a decimal point between the third and fourth digits of the complete number SUMMARY —001–009 Standard subdivisions —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas —2 Biography —3 Ancient world —4 Europe —5 Asia —6 Africa —7 North America —8 South America —9 Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds —001–008 Standard subdivisions —009 History If “history” or “historical” appears in the heading for the number to which notation 009 could be added, this notation is redundant and should not be used —[009 01–009 05] Historical periods Do not use; class in base number —[009 1–009 9] Geographic treatment and biography Do not use; class in —1–9 —1 Areas, regions, places in general; oceans and seas Not limited by continent, country, locality Class biography regardless of area, region, place in —2; class specific continents, countries, localities in —3–9 > —11–17 Zonal, physiographic, socioeconomic regions Unless other instructions are given, class -

Table of Contents

South Dakota Environments South Dakota State Historical Society Education Kit Table of Contents Goals and Materials ...................................................... 1 Teacher Resource Paper .............................................. 2-8 Word Find ..................................................................... 9 Word Find Key .............................................................. 10 Crossword Puzzle ......................................................... 11 Crossword Puzzle Key .................................................. 12 River Word Scramble .................................................... 13 River Word Scramble Key ............................................. 14 Learning from Objects ................................................... 15-16 Object Identification List ...................................... 17-22 Comparing Environments ............................................. 23-24 Word Cubes: Creating Sentences ................................ 25-26 Where Do I Live? SD Animals Over Time ..................... 27-33 Measuring Up ................................................................ 34-36 Fill It Up: Working a Water Tower ................................. 37-39 South Dakota Water Jeopardy! ..................................... 40-45 Above It All: Design a Water Tower .............................. 46-47 Sharing Oahe Dam Water ............................................. 48-49 Cattle, Sheep & Hogs: Reading Graphs ....................... 50-56 Great Grain Matchup ................................................... -

Stream Geomorphic Assessment Handbook, Database, and Spreadsheet Was the Collaborative Effort Of

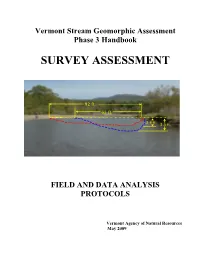

Vermont Stream Geomorphic Assessment Phase 3 Handbook SURVEY ASSESSMENT 92 ft. 63 ft. 2.4 ft. 3.5 ft. FIELD AND DATA ANALYSIS PROTOCOLS Vermont Agency of Natural Resources May 2009 Authorship and editing of the Phase 3 Stream Geomorphic Assessment Handbook, Database, and Spreadsheet was the collaborative effort of: Mike Kline DEC River Management Program Shayne Jaquith DEC River Management Program George Springston Norwich University Dept of Geology Barry Cahoon DEC River Management Program Larry Becker Vermont Geological Survey Funding for assessment protocol development has been provided by the: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Federal Emergency Management Agency Vermont Agency of Transportation Research Grant U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Green Mountain National Forest, Cooperative Cost Share Agreement Vermont Geological Survey State Map Grant Acknowledgements: Other Agency of Natural Resources staff who worked on the Phase 3 Handbook include Staci Pomeroy and Shannon Hill (River Management Program), Jim Ryan (Water Quality Division Planning Section), and Christa Alexander (Department of Fish and Wildlife). Special thanks to Brenda Clarkson of the DEC Information Technology Section for her help in database development. Pilot projects which greatly enhanced the development of the Phase 3 Handbook were made possible by Michele Boomhower of the Lamoille County Regional Commission; Dan McKinley, Steve Roy, and the fish crews of the U.S. Forest Service, Rochester Ranger District; and Eric Derleth and Chris Smith of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife -

Biological Inventories of Schoodic and Corea Peninsulas, Coastal Maine, 1996," for Transmission to the National Park Service, New England I System Support Office

FINAL REPORT I 'I Biological Inventories of Schoodic and Corea Peninsulas, Coastal Maine, 1996 I . I 'I I - ! June 30, 1999 I By: William E. Glanz, Biological Sciences Department, University of Maine and Bruce Connery, Acadia National Park, Co- Principal Investigators, With Chapters Contributed by Norman Famous, Glen Mittelhauser, Melissa Perera, Marcia Spencer-Famous, and Guthrie Zimmerman UNIVERSITY OF MAINE Department of Biological Sciences o 5751 Murray Hall o 5722 Deering Hall Orono. ME 04469-5751 Orono, ME 04469-5722 207/581-2540 207/581-2970 II FA-,{ 207/581-2537 FAX 207/581-2969 I·J 12 July 1999 Dr. Allan O'Connell Cooperative Park Studies Unit II South Annex A I I University of Maine II Orono, ME 04469 Dear Allan: Enclosed are three copies of the Final Report on "Biological Inventories of Schoodic and Corea Peninsulas, Coastal Maine, 1996," for transmission to the National Park Service, New England I System Support Office. I am delivering two additional copies to Bruce Connery, one for him as ! co-principal investigator and the other to be taken to James Miller at the US Navy base in Winter Harbor. This report is the final report for Amendment # 27 to the Cooperative Agreement between NPS and University of Maine (CA 1600-1-9016). The final version of this report incorporates most of the comments, editing, and suggestions from the reviews submitted to me. Bruce Connery revised the amphibian chapter to include all of Droege's suggestions; his recommendations for monitoring are outlined in the Discussion and Management Recommendations. Hadidian provided detailed editing suggestions, almost all of which were included in the amphibian, mammal and bird chapters. -

Stream Tables and Watershed Geomorphology Education

STREAM TABLES AND WATERSHED GEOMORPHOLOGY EDUCATION Karl D. Lillquist Geography and Land Studies Department, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, Washington 98926, [email protected] Patricia W. Kinner 5701 Waterbury Road, Des Moines, IA 50312, [email protected] ABSTRACT Watersheds are commonly addressed in introductory physical geography, environmental Watersheds are basic landscape units that are fund- science, earth science, and geology courses within amental to understanding resource and environ- mental sections on the hydrologic cycle and fluvial issues. Stream tables may be an effective way to learn geomorphology. Instructors in such courses often about watersheds and the dynamic processes, factors, attempt to link dynamic fluvial factors, processes, and and landforms within. We review the copious stream landforms to watersheds with traditional lectures, and table literature, present new ideas for assembling stream with topographic map- and airphoto-based laboratory tables, and provide a watershed approach to stream table exercises. Students subsequently may struggle to exercises. Our stream table’s compact size and low cost understand how fluvial landscapes evolve over time and permits the purchase and use of multiple units to how fluvial processes and factors affect everyday lives. This problem is especially acute when the vast majority maximize active learning. The included stream table of students enrolled in introductory courses are modules allow introductory students to experiment and non-science majors. Thus, the question explored here is observe the effects of factors–i.e., climate (Module how may scientists and non-scientists better learn about A–Precipitation, Overland Flow, and Channel Initiation the interrelated, dynamic fluvial factors, processes, and and Module B–Stream Discharge and Channel landforms of watersheds? Formation), topography (Module C–Watershed A potential solution to these problems is to use Topography and Channel Formation), land cover stream tables as watershed education tools.