Conflict Diamonds in Zimbabwe: Actors, Issues and Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blood Diamond 2006

Blood Diamond 2006 To an extent, Blood Diamond is a victim of its own length. While the film includes a number of disturbing political and sociological insights, the adventure story is tepid and loses momentum as the storyline bogs down. The main character, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, has an effective arc that is believable because it does not force him to act contrary to his nature, but it takes a long time for Blood Diamond to get us to DiCaprio's moment of recognition. Pacing issues aside, this is a well constructed movie - clearly the product of a director who understands how to make a top- notch motion picture. It looks great and sounds great. If only Edward Zwick's mastery of the medium had extended to pruning the screenplay and editing the final result, Blood Diamond might have been a tremendous film rather than one worthy of only a lukewarm recommendation. The story takes place in 1999 Sierra Leone, when the country is embroiled in a civil war. In this struggle, it's hard to determine which side is worse: the government or the rebels. As is often the case in this sort of bloodbath, atrocities abound and it's the innocent farmers and villagers caught in between who pay the price. Diamonds, one of the country's largest exportable commodities, are being smuggled out and purchased on the open market despite a supposed international ban on the purchase of so-called "conflict diamonds" or "blood diamonds." This historical background (which is more complicated as presented in the movie) is accurate, although the three primary characters embroiled in events are fictional. -

Blood Diamond

Blood Diamond Synopsis This story is about an ex-mercenary turned smuggler Danny Archer (Leonard DiCaprio) and a Mende fisherman Soloman Vandy (Djimon Hounsou). Amid the explosive civil war overtaking 1999 Sierra Leone, these men join for two desperate missions: recovering a rare pink diamond of immense value and rescuing the fisherman's son, conscripted as a child soldier into the brutal rebel forces ripping a swath of torture and bloodshed across the alternately beautiful and ravaged countryside. Introduction This resource is aimed at GCSE, AS, A2 and Highers students. The questions and points of discussion raised throughout this resource are connected to the official website for the film. Clip references refer to sequences that can be found on the official website: http://blooddiamondmovie.warnerbros.com/ In addition to the questions and discussion points raised, there is an existing Amnesty Resource (see link at the end of this document) developed to accompany the film and covers in-depth context and tasks. These materials combined touch on topics that teachers may find useful for Film and Media Studies, Citizenship, Politics and Business Studies. www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2007. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites. Trailer Analysis How is the setting established? Think about the types of shots that are used. The structure of the trailer shows us the credentials of the director. What does this tell us about the film’s potential audience? How important is this to you as a cinemagoer? Does it affect your choice? The trailer is designed to establish a sense of the story for the widest potential audience. -

Making Defiance Where He Built a Trucking Business with His Wife Lilka, (Played in the Film by Alexa Davalos)

24 | Lexington’s Colonial Times Magazine MARCH | APRIL 2009 a book, and a book is not a movie. So it has to be different. I cannot put everything that comes from years of work into two hours.’” “Did you actually talk to Tuvia?” prompted Leon Tec. His wife introduced him to the audience as “The troublemaker, my husband.” After the war Tuvia Bielski moved first to Israel and then to New York, Making Defiance where he built a trucking business with his wife Lilka, (played in the film by Alexa Davalos). Nechama Tec had spoken with him by telephone while researching her book “In the Lion’s Den,” but all attempts to meet in person had been stymied by Lilka Bielski’s excuses. Finally, Tec secured a meeting at the Bielskis’ Brooklyn home in May 1987. She hired a driver for the two-hour drive from Westport, Conn., and was greeted by Lilka, who told her that Tuvia had had a bad night, was very sick, and could not see her as planned. Tec said that she was leaving for Israel the next day on a research trip, and was politely insistent. “I want to get a sense of the man before I go,” she told Lilka. “So we’re going back and forth on the doorstep and she doesn’t let me in, and we hear a voice from the other room, ‘Let her in,’” recalled Tec. Tuvia Bielski, clearly weak and very sick, came out to meet her, dismissed the hovering Lilka, and sat down with Tec and her tape recorder. -

PDF (751.18 Kib)

arcade II Annie Jones Little Miss Sunshine: Thi5. staff writer film's very talented en emble ca t won a SAG award for their col- It's that time of year again - エ ゥ ュ セ for Holly- lectively heartfelt performances. wood hunks and silver screen starlets to squeeze Two of its actors, Alan Arkin and into designer eveningwear and pile into limos to the adorable Abagail Brc lin, arc gather and congratulate them elves yet again at nominated for their supporting the pinnacle of the wards season - the Oscars. roles. Little Miss Sunshine, a semi- ety of characters ranging from Ryan Go ling's tum as Arguably the most important night of the year for comcdy, is the underdog, but an Oscar win would a drug-addicted middle school teacher in HalfNelson the film industry, the Academy Awards has come cement the hopeful message of the movie itself. to Hollywood veteran Peter O'Toole's performance to represent the glamour of movies and provides The Departed: This crime drama set in Boston as an aging actor in Venus. The oft- nubbcd Leonardo us common folk with an oppor- DiCaprio received a nod for his tunity to drool over and dream work in Blood Diamond, but not about our favorite stars, ju t m for The Departed, a wa widely case there wasn't enough celeb- expected. The frontrunner here, rity worship already. This year's however, is Fore. t Whitaker, who ceremony should prove to be an portrays a Ugandan dictator in The especially exciting one, thanks Last King ofScotland. -

Teaching Social Studies Through Film

Teaching Social Studies Through Film Written, Produced, and Directed by John Burkowski Jr. Xose Manuel Alvarino Social Studies Teacher Social Studies Teacher Miami-Dade County Miami-Dade County Academy for Advanced Academics at Hialeah Gardens Middle School Florida International University 11690 NW 92 Ave 11200 SW 8 St. Hialeah Gardens, FL 33018 VH130 Telephone: 305-817-0017 Miami, FL 33199 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 305-348-7043 E-mail: [email protected] For information concerning IMPACT II opportunities, Adapter and Disseminator grants, please contact: The Education Fund 305-892-5099, Ext. 18 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.educationfund.org - 1 - INTRODUCTION Students are entertained and acquire knowledge through images; Internet, television, and films are examples. Though the printed word is essential in learning, educators have been taking notice of the new visual and oratory stimuli and incorporated them into classroom teaching. The purpose of this idea packet is to further introduce teacher colleagues to this methodology and share a compilation of films which may be easily implemented in secondary social studies instruction. Though this project focuses in grades 6-12 social studies we believe that media should be infused into all K-12 subject areas, from language arts, math, and foreign languages, to science, the arts, physical education, and more. In this day and age, students have become accustomed to acquiring knowledge through mediums such as television and movies. Though books and text are essential in learning, teachers should take notice of the new visual stimuli. Films are familiar in the everyday lives of students. -

Time to Rethink the Kimberley Process: the Zimbabwe Case - International Crisis Group

Time to Rethink the Kimberley Process: The Zimbabwe Case - International Crisis Group English Français Regions / Countries Browse by Publication Type Key Issues About Crisis Group Support Crisis Group ••••••• Other emailtwitter alerts Press Sitemap Text only RSS Login facebook Register Regions / Countries Homepage > Regions / Countries > Africa > Southern Africa > Zimbabwe > Time to Rethink the Kimberley Process: The Zimbabwe Case ● Africa ❍ Time to Rethink the Kimberley Process: The Zimbabwe Case Central Africa Thierry Vircoulon, On the African Peacebuilding Agenda | 4 Nov 2010 ❍ Horn of Africa On 11-12 September 2010, Zimbabwe auctioned diamonds from the controversial Marange mines. There was ❍ Southern Africa little international condemnation, especially compared to the controversy over the first sale of Marange diamonds in August. Since an export ban was imposed on diamonds from Marangein November 2009, the Kimberley ■ Angola Process (KP)[1] has permitted Zimbabwe to hold two auctions, although the country has not been able to guarantee that widespread human rights violations in the mines and smuggling have stopped. Criticised by both ■ Madagascar those who favour and those who oppose the ban, this unusual compromise demonstrates that the KP’s narrow ■ Zimbabwe definition of conflict diamonds is inadequate, and that the body must expand its authority if it is not to loose its credibility and legitimacy as the diamond-trade watchdog. ❍ West Africa A. Zimbabwe: Still Trying for Democracy Zimbabwe, a landlocked country of some 12.5 million inhabitants, is stuck in a decade-long political crisis and ● Asia struggling to move from dictatorship to democracy. For 28 years from independence in 1980, Robert Mugabe ● Europe ruled uninterrupted. -

Diamonds in the Rough

Diamonds in the Rough Human Rights Abuses in the Marange Diamond Fields of Zimbabwe Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-505-9 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org June 2009 1-56432-505-9 Diamonds in the Rough Human Rights Abuses in the Marange Diamond Fields of Zimbabwe Map of Zimbabwe and the Marange Diamond Fields ........................................................... 1 Glossary of Acronyms ......................................................................................................... 2 I. Summary ......................................................................................................................... 3 II. Recommendations .......................................................................................................... 7 To the Government of Zimbabwe ........................................................................................... 7 To the Government of South Africa ........................................................................................ 7 To the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme ..................................................................... -

The Kimberley Process: Conflict Diamonds, WTO Obligations, and the Universality Debate Tracey Michelle Price

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Journal of International Law 2003 The Kimberley Process: Conflict Diamonds, WTO Obligations, and the Universality Debate Tracey Michelle Price Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Price, Tracey Michelle, "The Kimberley Process: Conflict Diamonds, WTO Obligations, and the Universality Debate" (2003). Minnesota Journal of International Law. 115. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Journal of International Law collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles The Kimberley Process: Conflict Diamonds, WTO Obligations, and the Universality Debate Tracey Michelle Price" "Diamondsare forever, it is often said. But lives are not. We must spare people the ordeal of war, mutilations and death for the sake of conflict diamonds."' INTRODUCTION At the hands of rebels, dictators, and terrorists, diamonds have crystallized into a source of financing for conflict and civil wars, which have caused the deaths of more than two million people.2 These "conflict" diamonds have additionally threatened to tarnish the legitimate diamond trade by associating dia- monds with hardened brutality. The international community has attempted to curb the trade of conflict diamonds and pro- mote peace and stability in Angola, the Mano River Union states,3 and the Great Lakes region 4 of Africa. In the last two * LL.M. Candidate, Georgetown University Law Center; J.D., 1997, University of Baltimore School of Law; B.A., University of Georgia. -

Problems and Prospects in Marange Diamond Mining in Zimbabwe

GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DEVELOPMENT POLICY GOVERNANCE AND REFORMS AND NATIONAL BENEFITS: PRACTICE PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS IN MARANGE DIAMOND MINING IN ZIMBABWE Percy Fungayi Makombe September 2017 MASTER’S DISSERTATION SERIES No.2 GOVERNANCE REFORMS AND NATIONAL BENEFITS: PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS IN MARANGE DIAMOND MINING IN ZIMBABWE *Percy Fungayi Makombe Abstract Zimbabwe is among the top diamond-producing countries and is believed to hold a quarter of the world’s diamond reserves. Yet it is still one of the poorest countries as the economy is slumped and growth has slackened, and it is expected to further weaken. This study tracks the history of diamond mining at Marange diamond fields, describing what has played out since the discovery of huge diamond deposits in 2006.The study considers potential entry points to try and effect reform in diamond mining in the country. It also explores the governance options and their experience, distinguishing between domestic and global mechanisms and exploring the prospects for each. The study interrogates the strength and ability of various stakeholders to affect reform casting light on the politics and power dynamics at play. Key words: Marange, Diamods, Best Practice, Predatory, Governance, Zimbabwe, Zanu PF, Factions, Power, Community Trusts, Transparency, Resource Curse. Disclaimer: The working papers presented in this series showcase the dissertation research component of the MPhil in Development Policy and Practice offered by the University of the Cape Town’s Graduate School of Development Policy and Practice. The papers included in this series represent the top tier of work produced in this research component. The dissertations, which have gone rigorous assessment processes by both internal and external examiners are published in their entirety. -

Zimbabwe: the State, the Security Forces, and a Decade of Disappearing Diamonds

AN INSIDE JOB ZIMBABWE: THE STATE, THE SECURITY FORCES, AND A DECADE OF DISAPPEARING DIAMONDS SEPTEMBER 2017 AN INSIDE JOB ZIMBABWE: THE STATE, THE SECURITY FORCES, AND A DECADE OF DISAPPEARING DIAMONDS MOZAMBIQUE ZAMBIA Harare ZIMBABWE Gweru BOTSWANA Bulawayo Marange diamond fields SOUTH AFRICA AN INSIDE JOB ZIMBABWE: THE STATE, THE SECURITY FORCES, AND A DECADE OF DISAPPEARING DIAMONDS 03 CONTENTS SUMMARY 06 THE FIND 12 THE COMPANIES 14 Limited information about production and revenue flows frustrates oversight 16 Company ownership information is guarded as a state secret 18 Zimbabwe’s diamonds are reaching international markets with minimal scrutiny 19 OFF-BUDGET FUNDING TO THE SECURITY SECTOR 20 Marange diamonds fund the CIO through Kusena? 22 Secret memos reveal CIO involvement in Marange 23 CIO linked diamonds tendered on the international market 26 Diamonds and the military: Anjin and Jinan 28 Anjin is part-owned by a military-linked company 28 Were EU sanctions violated by Antwerp tenders? 29 The Future of Anjin 33 Jinan is closely linked to Anjin 33 DMC: FROM SMUGGLERS TO MINERS? 34 Marange diamonds smuggled prior to Kimberley Process certification 35 From diamond smugglers to diamond miners 36 DMC Principal may also be implicated in global smuggling networks 36 MBADA, CRONIES, AND STATE SECRETS 38 Concealment of Mbada’s beneficial owners 38 Transfrontier makes extensive use of secrecy jurisdictions 39 Robert Mhlanga likely controls Transfrontier 39 THE FUTURE OF MARANGE 46 RECOMMENDATIONS 47 ENDNOTES 50 04 ACRONYMS AFECC(G) Anhui -

Produced with the Participation of Blue Ice Docs

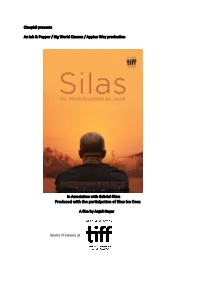

Cinephil presents An Ink & Pepper / Big World Cinema / Appian Way production In Association with Gabriel Films Produced with the participation of Blue Ice Docs A film by Anjali Nayar World Premiere at 80 minutes English, Liberian English • • Canada/South Africa/Kenya 2017 • Contacts at TIFF: Producer: Producer: Steven Markovitz Anjali Nayar Big World Cinema Ink & Pepper Productions E: [email protected] E: T: +27 83 2611 044 T: +1- 415-910-4625 Sales Agent: Publicist: Philippa Kowarsky Charlene Coy Cinephil C2C Communications E: [email protected] E: [email protected] T: +972 3 566 4129 T: +1-416-451-1471 Tagline: No more business as usual Logline With a network of dedicated citizen reporters by his side, seasoned Liberian activist Silas Siakor challenges the corrupt and nepotistic status quo in his fight for local communities. Synopsis Liberian activist, Silas Siakor is a tireless crusader, fighting to crush corruption and environmental destruction in the country he loves. Through the focus on one country, Silas is a global tale that -

The Blood Diamond

1 The Blood Diamond The Story, Function of The Music, Tendencies Kodjo D. Attivor THESIS – Summer 2014 Advisor: Lucio Godoy Scoring for Film, Television, and Video Games Berklee College of Music 2 Table of Content Introduction 3 Synopsis 4 The Composer 6 Function of the music 7 Cue List 11 Source Music 13 Repetition – Music Editing 14 Final Thought 15 References 16 Transcription See Attachment 3 Introduction In the field of movie production, film scoring is essential; it helps reveal the film genre as the music sets the mood of the plot. Music: Science and art, functions as an emotion enhancer. It helps illustrate movements, create atmosphere, produce a sense of space, fictitious imaginations, creates a perception of time, and cleverly controls the viewer’s perception. It has been proven that soundtracks control the emotions of the viewer as it does in the “Blood Diamond.” Obviously, the music sets the geographic and cultural references for the “Blood diamond film.” The “Blood Diamond” is an adventure and drama film that relates the true story of the Sierra Leone genocide were the people fought and killed fiercely in a political war that generated into one of the most controversial tribal war around a stone called “Diamond.” The music enhanced the story and the physiological consequences of the images even though the music has not been pronounced at all times. Successfully, the composer wrote all original themes and some of the source music for the movie. The approach of the hybrid orchestration confirmed the composer’s skills and professionalism as the production techniques enhanced its function.