Two-Way Migration of Lychnis Wilfordii Caused by the Circular Landform Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In This Issue

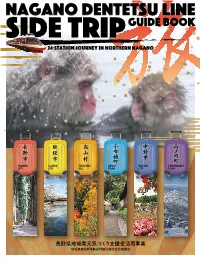

to Kanazawa In this issue to JoetsuJCT Toyoda-Iiyama I.C P.12 Nakano City Shinsyu-Nakano I.C P.14 Yudanaka Station Shinsyu-Nakano P.04 P.10 Station Nagano Yamanouchi Town Nagano City Obuse Town Snow Monkey Obuse Dentetsu Station Line Obuse P.A P.08 Suzaka Station Takayama Vill Nagano Zenkoji Temple Station P.06 Nagano I.C Expressway Suzaka City Nagano Expressway Joshinetsu Koshoku J.C.T Nagano Prefecture Nagano City Suzaka City Greetings from Northern 1Zenkoji × Soba× Oyaki p04 2 What´s Misosuki Don ? p06 Nagano! Come take a JoshinetsuExpressway Shinshu Matsumoto Airport Mathumoto I.C JR Hokuriku Shinkansen to Tokyo journey of 24 stations ! 02 Enjoy a scenic train ride through the 03 Nagano Hongo Kirihara Kamijyo Hino Kita-suzaka Entoku Nakano-Matsukawa Fuzokuchugakumae Murayama Shiyakushomae Shinano-Yoshida Suzaka Sakurasawa Shinsyu-Nakano Shinano-Takehara Gondo Obuse Zenkojishita Asahi Tsusumi Yomase Yudanaka Yanagihara Nagano countryside on the Nagano Dentetsu line. Nicknamed “Nagaden”, min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 3 min 4 min 4 min 2 min 4 min 3 min 4 min 3 min 4 min 2 min 2 min 3 the train has linked Nagano City with Suzaka, Obuse, Nakano and Yamanouchi since it opened in 10- June, 1922. Local trains provide min 2 min 2 min 3 min 2 min 3 min 8 min 6 min 9 12min Limited B express leisurely service to all 24 stations min 2 14min min 6 min 9 12min along the way, while the express trains Limited A express such as the “Snow Monkey” reaches Takayama Village Obuse Town 【About express train 】 Yudanaka from Nagano Station in as quickly as 44 minutes. -

Nagano Regional

JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation Focusing mainly on Nagano Prefecture Regional Map Nagano Prefecture, where the 1998 winter Olympics were held, is located in the center of Japan. It is connected to Tokyo in the southeast, Nagoya in the southwest, and also to Kyoto and Osaka. To the northeast you can get to Niigata, and to the northwest, you can get to Toyama and Kanazawa. It is extremely convenient to get to any major region of Japan by railroad, or highway bus. From here, you can visit all of the major sightseeing area, and enjoy your visit to Japan. Getting to Nagano Kanazawa Toyama JR Hokuriku Shinkansen Hakuba Iiyama JR Oito Line JR Hokuriku Line Nagano Ueda Karuizawa Limited Express () THUNDER BIRD JR Shinonoi Line JR Hokuriku Matsumoto Chino JR Chuo Line Shinkansen JR Chuo Line Shinjuku Shin-Osaka Kyoto Nagoya Tokyo Narita JR Tokaido Shinkansen O 二ニ〕 kansai Chubu Haneda On-line゜ Booking Hotel/Ryokan & Tour with information in Japan CLICK! CLICK! ~ ●JAPAN iCAN.com SUN 廊 E TOURS 四 ※All photos are images. ※The information in this pamphlet is current as of February 2019. ≫ JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation ヽ ACCESS NAGANO ヽ Narita International Airport Osaka Haneda(Tokyo ダ(Kansai International International Airport) Airport) Nagoya Snow Monkey (Chubu Centrair The wild monkeys who seem to International Airport) enjoy bathing in the hot springs during the snowy season are enormously popular. Yamanouchi Town, Nagano Prefecture Kenrokuen This Japanese-style garden is Sado ga shima Niigata (Niigata Airport) a representative example of Nikko the Edo Period, with its beauty Niigata This dazzling shrine enshrines and grandeur. -

Matsumoto City Cycling Stadium

Matsumoto City Cycling Stadium Matsumoto City Summary Matsumoto City lies more or less at the center of the Japan. Utsukushigahara Highland (2,000m) situates east of the city and 3,000m-class “Japan Northern Alps” mountain range is lying around west. The national treasure Matsumoto Castle is located in the heart of the city and it boasts over 400 years of history. As well as historic castle, there is world’s famous mountain scenic area “Kamikochi”. In addition, there are 16 Onsen (hot springs) too. Annually more than 5 million tourists are visiting these charms which make the city popular destination. The Matsumoto City is located at 600m above sea level. It is comfortable environment as the climate is relatively cool and low humidity in a summer. About Matsumoto Area 978.47km² Elevation 592.21m Coordinates 36°14' 17''N 137°58'19''E Population 240,941 Average Temperature July 23.6℃ August 24.7℃ Transport to Matsumoto ・By train: 2hrs 30min from Shinjuku(Tokyo) by JR “Azusa” limited express train ・By car: About 3hrs from Tokyo through Chuo-Highway and Nagano-Highway. History・Culture・Nature National Treasure Matsumoto Castle Matsumoto City Museum of Art Matsumoto Castle is the oldest castle in The museum exhibits the creations of Japan and also designated as national the world’s famous artist Yayoi Kusama. treasure. The combination of the black and white castle and Japan Northern Alps is beautiful. Kamikochi Utsukushigahara Highland Kamikochi is the one of the world’s It is the highest plateau in the country. famous scenic area backed by the It commands a magnificent view of Japan Northern Alps. -

Japan Alps Winter 6 Days: Nagano and Gifu

長 野 Japan Alps Winter 6 days: Nagano and Gifu Introduction Lying at the heart of central Japan, Shinshu and Hida Please ask for information about our tour extensions: - the traditional names for Nagano and northern Gifu spend more time in the Hida region with our Prefectures - have flourished since ancient times as a Takayama extension, visiting the UNESCO thatched- cultural crossroads between east and west Japan. The roof community of Shirakawa-go and the wonderful region is also home to the Northern Alps, a range of teahouses of Kanazawa; enjoy spectacular views of 3,000-metre high mountains often called “the roof Mount Fuji from the Hakone hot-spring area and of Japan”, and an area of great scenic beauty, offering the rural village of Oshino Mura; be charmed by the superb views, unspoiled natural landscapes and some of peaceful agricultural community of Asuka while staying Japan’s best Onsen hot springs. in a delightful small inn or with a local family for a unique homestay experience. Explore the feudal castle town of Matsumoto, then head into the Oku-Hida mountains to discover the biodiverse highlands and secluded Onsen hot springs. Continue onwards to Hida-Furukawa and Takayama. An unforgetable winter experience. Yudanaka Onsen Snow Monkeys Choose a pre-tour 1-night extension to visit Yudanaka Onsen hot-spring village in northern Nagano. Here the famous Japanese macaque “snow monkeys” come to warm themselves in the outdoor hot-spring baths during the cold winters, enjoying the natural setting just like humans. 1 DETAILS TOUR LENGTH AND PRICES SEASON Train tickets and pre-bookable bus 6 days Recommended from January until tickets for intermediate journeys; March. -

Contact Information for the Core Organization

●Knowledge Cluster Initiative Contact Information for the Core Organization Knowledge Clusters: The Second Stage (Active) Knowledge Clusters: Innovative Stage (Active) Northem Advancement Center for Science & Technology(NOASTEC FOUNDATION) Hakodate Regional Industry Promotion Organization Hokkaido University, Northern Campus Research Building Ⅲ 3F Hokkaido Area Adress: 379 Kikyocho, Hakodate City, Hokkaido 041-0801, JAPAN North 21 West 11 Kita-Ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido 001-0021, JAPAN Hakodate Area (with Sapporo as the core) TEL:+81-11-757-2288 FAX:+81-11-757-2289 URL:http://www.bio-sss.jp/ TEL:+81-138-34-2600 FAX:+81-138-34-2601 URL:http://www.techakodate.or.jp/ Knowledge Cluster Initiative Promotion Section, Intelligent Cosmos Research Institute Co., Ltd. Yamaguchi prefectural Industrial technology Institute Greater Sendai Area 7F, 1-3-1, Chuo, Aoba-ku, Sendai City, Miyagi 980-6107, JAPAN Yamaguchi 4-1-1 ASUTOPIA, Ube City, Yamaguchi 755-0195, JAPAN TEL:+81-22-346-9237 FAX:+81-22-346-9238 URL:http://www.sendai-cyber.icr-eq.co.jp/ TEL:+81-836-53-5061 FAX:+81-836-53-5072 URL:http://www.iti-yamaguchi.or.jp/ Knowledge Cluster Promotion Office, The Hokuriku Industrial Advancement Center Industry and Academia Collaboration Department, Tokushima Industrial Promotion Organization Toyama/Ishikawa 2-2-15, Katamachi, Kanazawa, Ishikawa, 920-0981, JAPAN Tokushima 11-2 Nishigai, Saika-cho, Tokushima 770-8021, JAPAN TEL:+81-76-210-7400 FAX:+81-76-210-7450 URL:http://www.hiac.or.jp/cluster/ TEL:+81-88-669-4757 FAX:+81-88-669-4759 URL:http://www.our-think.or.jp/ Nagano Techno Foundation Biotechnology Division, Kurume Research Park, Co., Ltd. -

KAKEHASHI Project (United States of America) Inbound Program for High School Students the 2Nd Slot Program Report

KAKEHASHI Project (United States of America) Inbound program for High School Students the 2nd Slot Program Report 1. Program Overview Under the “KAKEHASHI Project” of Japan’s Friendship Ties Program, 100 high school students and supervisors from the U.S. visited Japan from July 23 to July 30, 2019 to participate in the program aimed at promoting their understanding of Japan with regard to Japanese politics, economy, society, culture, history, and foreign policy. Through the lectures, observations and interactions with Japanese people etc., the participants enjoyed a wide range of opportunities to improve their understanding of Japan and shared their individual interests and experiences on social media. Based on their findings and learning in Japan, each group of participants made a presentation in the final session and reported on the action plans to be taken after returning to the U.S. [Participating Countries and Numbers of Participants] United States of America: 100 participants, (Breakdown) Group A (50participants): Glendale Unified School District (State of California) Columbus North International School (State of Ohio) Group B (50 participants): Forest Hills High School (State of New York) Boston Latin Academy (Commonwealth of Massachusetts) [Prefectures Visited] Tokyo (All), Nagano (Group A), Aichi and Mie (Group B) 2. Program Schedule 7/23(Tue) 【Arrival】 7/24(Wed) 【Orientation】 【Lecture】Dr. KIMURA Hideo, Executive Managing Director, Strategic International Management Associates (SIMA) (Japan Today) (1) Group A:Nagano (2) Group -

Regional Map Nagano Prefecture, Where the 1998 Winter Olympics Were Held, Is Located in the Center of Japan

JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation Focusing mainly on Nagano Prefecture Regional Map Nagano Prefecture, where the 1998 winter Olympics were held, is located in the center of Japan. It is connected to Tokyo in the southeast, Nagoya in the southwest, and also to Kyoto and Osaka. To the northeast you can get to Niigata, and to the northwest, you can get to Toyama and Kanazawa. It is extremely convenient to get to any major region of Japan by railroad, or highway bus. From here, you can visit all of the major sightseeing area, and enjoy your visit to Japan. Getting to Nagano Kanazawa Toyama JR Hokuriku Shinkansen Hakuba Iiyama JR Oito Line JR Hokuriku Line Nagano Ueda Karuizawa Limited Express ( THUNDER BIRD) JR Shinonoi Line JR Hokuriku Matsumoto Chino JR Chuo Line Shinkansen JR Chuo Line Shinjuku Shin-Osaka Kyoto Nagoya Tokyo Narita JR Tokaido Shinkansen kansai Chubu Haneda On-line Booking Hotel/Ryokan & Tour with information in Japan CLICK! CLICK! ※All photos are images. ※The information in this pamphlet is current as of February 2019. JTB-Affiliated Ryokan & Hotels Federation ACCESS NAGANO Narita International Airport Osaka Haneda(Tokyo (Kansai International International Airport) Airport) Nagoya Snow Monkey (Chubu Centrair The wild monkeys who seem to International Airport) enjoy bathing in the hot springs during the snowy season are enormously popular. Yamanouchi Town, Nagano Prefecture Kenrokuen This Japanese-style garden is Sado ga shima Niigata (Niigata Airport) a representative example of Nikko the Edo Period, with its beauty Niigata This dazzling shrine enshrines and grandeur. It is considered Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first one of the three best gardens Hokuriku Shogun who began the Edo in Japan. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

Effects of the Mid Niigata Prefecture Earthquake in 2004 on Dams By

Effects of the Mid Niigata Prefecture Earthquake in 2004 on dams by Nario Yasuda1, Masafumi Kondo2, Takayuki Sano3, Hidetaka Yoshioka4, Yoshikazu Yamaguchi5, Takashi Sasaki6 and Naoki Tomita7 ABSTRUCT lowered at some facilities. Due to the Mid Niigata Prefecture Earthquake 2. OUTLINE OF THE SITE INVESTIGATIONS that occurred in October 2004, several embankment dams and other off-stream Fig. 1 shows the locations of the investigated impounding facilities for irrigation and power dams, which are shown in Table 2, and the generation located near hypocenter of the epicenter. The main purposes of the investigations earthquake were suffered some changes in were to verify the occurrence or nonoccurrence of condition or damage such as cracks on their dam earthquake-induced changes in the conditions of bodies. the dams in detail, collect earthquake motion In this paper, results of site investigations on records, investigate dam deformation and changes the changes in condition or damage found at dams in leakage/seepage rates, and identify the and regulating reservoirs after the earthquake are tendencies of such changes, if any. This report reported. The records of strong earthquake motion focuses on the earthquake-induced changes and observed at the dam sites near hypocenter of the damage to the regulating reservoirs for power earthquake are also indicated and discussed. generation of East Japan Railway Company (JR East) and the embankment dams built for KEYWORDS : the Mid Niigata Prefecture irrigation purposes that have been suffered Earthquake in 2004, dam, site investigations, relatively large changes in condition. The report earthquake motion also deals with the recorded earthquake motions at dam sites located near the hypocenter of the 1. -

Tour Itinerary

GEEO ITINERARY x-JAPAN – Summer Day 1: Tokyo Arrive at any time. On arrival, please check the notice board in the hotel entrance for details of the time and place of the meeting. As fellow group members will be arriving throughout the day, there are no planned activities until the group meeting in the early evening (6:00 p.m. or 7:00 p.m.). After the group meeting, consider heading out for a group dinner. Day 2: Tokyo Take a walking tour of eclectic modern Tokyo from the hub of Shinjuku to Shibuya through to Harajuku. The rest of the day is free for exploring more of the city. Your tour leader will lead the group on a walking tour of eclectic modern Tokyo from the hub of Shinjuku to Shibuya through to Harajuku. The rest of the day is free for exploring more of the city. Day 3: Tokyo/Nagano Journey to Nagano, located in the Japanese Alps and host city of the 1998 Winter Olympics. Visit the world-famous Jigokudani Monkey Park and watch Japanese snow monkeys bathing in the natural hot springs. Today we board a bullet train and journey to Nagano, located in the Japanese Alps and host city of the 1998 Winter Olympics. We will visit the Jigokudani Monkey Park, where wild snow monkeys can be seen bathing in the natural hot springs. The pool where most of the monkeys soak is man-made, fed by the hot springs. Along the walking paths up to the pools other monkeys tend to stop and watch visitors curiously. -

Koshinetsu and Shizuoka Soy Sauce Brewing Development of a Multipurpose Seasoning and Pickling Culture Nami Fukutome, Associate Professor, Tokyo Seiei College

Soy Sauce in Koshinetsu and Shizuoka Koshinetsu and Shizuoka Soy Sauce Brewing Development of a Multipurpose Seasoning and Pickling Culture Nami Fukutome, Associate Professor, Tokyo Seiei College 1. Yamanashi Natives Love Dashi-tsuyu the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 when a large amount In Yamanashi Prefecture, following on the heels of five of Shinshu-produced miso that had been stockpiled at an major producers is a brewery that leads the regional unused sericulture (silkworm culture) farm was released industry as the top mid-size maker. Founded in 1872, as emergency supplies. With the decline of the sericulture the brewery recently introduced a machine for large- industry, many businesses switched to miso brewing, but were scale production of koji, allowing it not only to meet later consolidated into large-scale manufacturers. In contrast, its own needs but also supply other companies. It also the local soy sauce brewing industry is dotted with cottage introduced a bottling machine that can even fill liquids industry–style brewers handcrafting their moromi mash. like dressings that contain solids, and is invested in OEM A brewer from northern Nagano near the prefectural border manufacturing. Another defining feature of this soy sauce with Niigata, is in an area famous for Togakushi Soba. I brewery is its focus on tsuyu soup bases and tare sauces. learned that the correct way to eat this dish is to soak the In particular, the dashi-tsuyu launched by the brewery in noodles deep in the tsuyu, slurping the soup base and soba 1964 was a big hit, creating a boom alongside mentsuyu noodles together, unlike in Tokyo where noodles are barely (noodle soup base) and dashi shoyu (combined stock and dipped. -

Living Guide for Foreign Residents in Matsumoto City St Issued On: March 31 , 2018

英 語 Living Guide for Foreign Residents in Matsumoto City This guidebook contains information necessary for life in Matsumoto. If you have any trouble, or something you don’t understand, please call the number below. Our staff will be available to listen to any questions you have. ―Multicultural Plaza (Tabunka Kyosei Plaza)― TEL 0263-39-1106 Table of Contents Consultation and Advice Counter 1 Emergency Phone Numbers 2 Please Prepare for Earthquakes 4 If a Typhoon or Heavy Rain Comes 5 Resident Registration 6 The Residence Card 7 Status of Residence 8 Rules for Living 10 Moving House 12 Neighborhood Groups 13 Naturalization, Choosing Your Nationality 14 Marriage & Divorce 15 Pregnancy & Birthing 17 Child Raising 20 Japanese Schools 22 Sickness & Injury 26 Pensions 28 Taxes 30 Driver’s Licenses 31 Jobs 33 Consultation and Advice Counter ●Matsumoto City Multicultural Plaza (Tabunka Kyosei Plaza) The place to inquire about any matter. Please come any time if you have a difficulty or something you don’t understand. We offer consultation services in foreign Languages, (Portuguese, Thai, Chinese, English, Tagalog, etc). Please call to ask about an available time. This service is free. ― Examples ― Q:Where can I go to learn Japanese? Q:I received a letter from the city office, but I can’t read it. Q:My employer fired me. What should I do now? Q:My Japanese husband and I got divorced. Can I continue to stay in Japan? ■Location The 3rd Floor of the M Wing Building(1-18-1 Chuo, Matsumoto City) ■Opening Hours Mon-Fri: 9:00~22:00(Please come by 21:00.) Weekends and National Holidays:9:00~17:00 ■Closed The 2nd and 4th Wednesdays and from Dec 29th to Jan 3rd Inquiries; Matsumoto City Multicultural Plaza TEL 0263-39-1106 ●Consultation Service in Portuguese We have consultation service in Portuguese.