Decorated Flat Surfaces and the Invention of Design in Armenian Architecture of the Bagratids Era1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eduard L. Danielyan Progressive British Figures' Appreciation of Armenia's Civilizational Significance Versus the Falsified

INSTITUTE OF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA EDUARD L. DANIELYAN PROGRESSIVE BRITISH FIGURES’ APPRECIATION OF ARMENIA’S CIVILIZATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE VERSUS THE FALSIFIED “ANCIENT TURKEY” EXHIBIT IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM YEREVAN 2013 1 PUBLISHED WITH THE APPROVAL OF THE SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL OF THE INSTITUTE OF HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA This work was supported by State Committee of Science MES RA, in frame of the research project № 11-6a634 “Falsification of basic questions of the history of Armenia in the Turkish-Azerbaijani historiogrpahy”. Reviewer A.A.Melkonyan, Doctor of History, corresponding member of the NAS RA Edited by Dr. John W. Mason, Pauline H. Mason, M.A. Eduard L. Danielyan Progressive British Figures’ Appreciation of Armenia’s Civilizational Significance Versus the Falsified “Ancient Turkey” Exhibit in the British Museum This work presents a cultural-spiritual perception of Armenia by famous British people as the country of Paradise, Noah’s Ark on Mt. Ararat-Masis and the cradle of civilization. Special attention is paid in the book to the fact that modern British enlightened figures call the UK government to recognize the Armenian Genocide, but this question has been politicized and subjected to the interests of UK-Turkey relations, thus being pushed into the genocide denial deadlock. The fact of sheltering and showing the Turkish falsified “interpretations” of the archaeological artifacts from ancient sites of the Armenian Highland and Asia Minor in the British Museum’s “Room 54” exhibit wrongly entitled “Ancient Turkey” is an example of how the genocide denial policy of Turkey pollutes the Britain’s historical-cultural treasury and distorts rational minds and inquisitiveness of many visitors from different countries of the world.The author shows that Turkish falsifications of history have been widely criticized in historiography. -

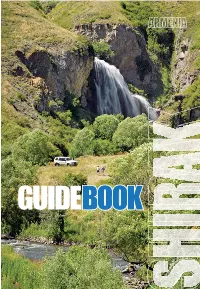

Shirak Guidebook

Wuthering Heights of Shirak -the Land of Steppe and Sky YYerevanerevan 22013013 1 Facts About Shirak FOREWORD Mix up the vast open spaces of the Shirak steppe, the wuthering wind that sweeps through its heights, the snowcapped tops of Mt. Aragats and the dramatic gorges and sparkling lakes of Akhurian River. Sprinkle in the white sheep fl ocks and the cry of an eagle. Add churches, mysterious Urartian ruins, abundant wildlife and unique architecture. Th en top it all off with a turbulent history, Gyumri’s joi de vivre and Gurdjieff ’s mystical teaching, revealing a truly magnifi cent region fi lled with experi- ences to last you a lifetime. However, don’t be deceived that merely seeing all these highlights will give you a complete picture of what Shirak really is. Dig deeper and you’ll be surprised to fi nd that your fondest memories will most likely lie with the locals themselves. You’ll eas- ily be touched by these proud, witt y, and legendarily hospitable people, even if you cannot speak their language. Only when you meet its remarkable people will you understand this land and its powerful energy which emanates from their sculptures, paintings, music and poetry. Visiting the province takes creativity and imagination, as the tourist industry is at best ‘nascent’. A great deal of the current tourist fl ow consists of Diasporan Armenians seeking the opportunity to make personal contributions to their historic homeland, along with a few scatt ered independent travelers. Although there are some rural “rest- places” and picnic areas, they cater mainly to locals who want to unwind with hearty feasts and family chats, thus rarely providing any activities. -

Armenia, Republic of | Grove

Grove Art Online Armenia, Republic of [Hayasdan; Hayq; anc. Pers. Armina] Lucy Der Manuelian, Armen Zarian, Vrej Nersessian, Nonna S. Stepanyan, Murray L. Eiland and Dickran Kouymjian https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T004089 Published online: 2003 updated bibliography, 26 May 2010 Country in the southern part of the Transcaucasian region; its capital is Erevan. Present-day Armenia is bounded by Georgia to the north, Iran to the south-east, Azerbaijan to the east and Turkey to the west. From 1920 to 1991 Armenia was a Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR, but historically its land encompassed a much greater area including parts of all present-day bordering countries (see fig.). At its greatest extent it occupied the plateau covering most of what is now central and eastern Turkey (c. 300,000 sq. km) bounded on the north by the Pontic Range and on the south by the Taurus and Kurdistan mountains. During the 11th century another Armenian state was formed to the west of Historic Armenia on the Cilician plain in south-east Asia Minor, bounded by the Taurus Mountains on the west and the Amanus (Nur) Mountains on the east. Its strategic location between East and West made Historic or Greater Armenia an important country to control, and for centuries it was a battlefield in the struggle for power between surrounding empires. Periods of domination and division have alternated with centuries of independence, during which the country was divided into one or more kingdoms. Page 1 of 47 PRINTED FROM Oxford Art Online. © Oxford University Press, 2019. -

Armenian Architecture Through the Pages of Robert G. Ousterhout's Book

790 A. Kazaryan УДК: 72.033 ББК: 85.11 А43 DOI: 10.18688/aa199-7-70 A. Kazaryan Armenian Architecture through the Pages of Robert G. Ousterhout’s Book “Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands”1 Among the historians of Byzantine architecture, professor of the University of Pennsylvania Robert G. Ousterhout holds a prominent place due to the nature of his scientific interests and distinct individuality manifested in a combination of full-scale study of monuments and skillful formulation of historical and theoretical issues. A new perspective on the development of building art, architectural composition, function and symbolic content of buildings and complexes is common to his articles and monographs on the architecture of Constantinople, Jerusalem, and Cappadocia. In his new monograph “Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands” [10], along with the Byzantine regions, R. Ousterhout pays attention to the architecture of Christian countries that surrounded Byzantium and had close historical and cultural ties with it, as well as Muslim political entities on the territories torn away from the empire. This fact sets this book apart from most of the previous review studies on Byzantine art and architecture, in which only those territories related to Christian countries were included in the circle of the problems discussed. Some other innovations include a survey of the post-Byzantine architecture up to its later forms of development, discussion of the problem of reproducing the ideas of Byzantine architecture to the rival powers — the Ottoman and Russian empires — and, in the epilogue of the book, to the architecture of Modern and Contemporary times. -

Armenian Church Timeline

“I should like to see any power of the world destroy this race, this small tribe of unimportant people, whose history is ended, whose wars have all been fought and lost, whose structures have crumbled, whose literature is unread, whose music is unheard, whose prayers are no longer uttered. Go ahead, destroy this race. Let us say that it is again 1915. There is war in the world. Destroy Armenia. See if you can do it. Send them from their homes into the desert. Let them have neither bread nor water. Burn their houses and their churches. See if they will not live again. See if they will not laugh again.” –William Saroyan ARMENIAN CHURCH TIMELINE 1. Birth of the Holy Savior Jesus Christ in Bethlehem. Years later, an Armenian prince, Abqar of Edessa (Urfa), invites Jesus to his court to cure him of an illness. Abgar’s messengers encounter Jesus on the road to Calvary and receive a piece of cloth impressed with the image of the Lord. When the cloth is brought back to Edessa, Abgar is healed. 33. Crucifixion, Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus Christ On the 50th day after the Resurrection (Pentecost)the Holy Spirit descends upon the Apostles gathered in Jerusalem. 43. The Apostle Thaddeus comes to Armenia to preach Christianity. He is martyred in Artaz in southeastern Armenia. 66-68. The Apostle Bartholomew preaches in Armenia. He is martyred in Albac, also in southeastern Armenia. The Armenian Church is apostolic because of the preaching of the Apostles Thaddeus and Bartholomew in Armenia. 75. King Sanatruk and his daughter, Sandoukht convert to Christianity. -

Armenian Tourist Attraction

Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... rediscover armenia guide armenia > tourism > rediscover armenia guide about cilicia | feedback | chat | © REDISCOVERING ARMENIA An Archaeological/Touristic Gazetteer and Map Set for the Historical Monuments of Armenia Brady Kiesling July 1999 Yerevan This document is for the benefit of all persons interested in Armenia; no restriction is placed on duplication for personal or professional use. The author would appreciate acknowledgment of the source of any substantial quotations from this work. 1 von 71 13.01.2009 23:05 Armenian Tourist Attractions: Rediscover Armenia Guide http://mapy.mk.cvut.cz/data/Armenie-Armenia/all/Rediscover%20Arme... REDISCOVERING ARMENIA Author’s Preface Sources and Methods Armenian Terms Useful for Getting Lost With Note on Monasteries (Vank) Bibliography EXPLORING ARAGATSOTN MARZ South from Ashtarak (Maps A, D) The South Slopes of Aragats (Map A) Climbing Mt. Aragats (Map A) North and West Around Aragats (Maps A, B) West/South from Talin (Map B) North from Ashtarak (Map A) EXPLORING ARARAT MARZ West of Yerevan (Maps C, D) South from Yerevan (Map C) To Ancient Dvin (Map C) Khor Virap and Artaxiasata (Map C Vedi and Eastward (Map C, inset) East from Yeraskh (Map C inset) St. Karapet Monastery* (Map C inset) EXPLORING ARMAVIR MARZ Echmiatsin and Environs (Map D) The Northeast Corner (Map D) Metsamor and Environs (Map D) Sardarapat and Ancient Armavir (Map D) Southwestern Armavir (advance permission -

Saint Gayane Church

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Seminář dějin umění Saint Gayane Church Bakalárska diplomová práca Autor: Michaela Baraničová Vedúci práce: prof. Ivan Foletti, MA, Docteur es Lettres Brno 2020 ii Prehlasujem, že som svoju bakalársku diplomovú prácu vypracovala samostatne a uviedla všetkú použitú literatúru a pramene. .............................................................. Podpis autora práce iii iv On the ancient peak of Ararat The centuries have come like seconds, And passed on. The swords of innumerable lightnings Have broken upon its diamond crest, And passed on. The eyes of generations dreading death Have glanced at its luminuos summit, And passed on. The turn is now yours for a brief while: You, too, look at its lofty brow, And pass on! Avetik Isahakyan, “Mount Ararat”, in Selected Works: Poetry and Prose, ed. M. Kudian, Moscow 1976. v vi My first sincere thanks belong to my thesis’ supervisor, prof. Ivan Foletti, for his observations, talks and patience during this time. Especially, I would like to thank him for introducing me to the art of Caucasus and giving me the opportunity to travel to Armenia for studies, where I spent five exciting months. I would like to thank teachers from Yerevan State Academy of Arts, namely to Gayane Poghosyan and Ani Yenokyan, who were always very kind and helped me with better access of certain Armenian literature. My gratitude also belongs to my friends Susan and colleagues, notably to Veronika, who was with me in Armenia and made the whole experience more entertaining. To Khajag, who helped me with translation of Armenian texts and motivating me during the whole process. It´s hard to express thanks to my amazing parents, who are constantly supporting me in every step of my studies and life, but let me just say: Thank you! vii viii Content Introduction.........................................................................1 I. -

The 7 Most Endangered 2016 Archaeological Site of Ererouyk And

The 7 Most Endangered 2016 Programme run by Europa Nostra, the Voice of Cultural Heritage in Europe, in partnership with the European Investment Bank Institute Archaeological Site of Ererouyk and village of Anipemza, Armenia Technical report Table of contents 1. Summary and recommendations 2. Location and purpose 3. Context 4. Description and scope 5. Technical aspects 6. Implementation and calendar 7. Environment, sustainability, social 8. Use, demand, market 9. Investment cost 10. Potential alliances and sources for funding the project Appendices 1. Rationale for investing in tourism 2. Detailed description of the site and its components 3. Details related to the scope of the project 4. Methodological approach – Guidelines for the implementation of works 5. Promoters and potential partners 6. Meetings, missions and actions taken so far 7. Photographic support and general map of the site Mario Aymerich and Guy Clausse Technical Consultants, EIB Institute Luxembourg, March 2017 1 1. Summary Foreword This report is prepared within the cooperation on the 7 Most Endangered Heritage Sites between Europa Nostra and the European Investment Bank Institute. The content of this report is the result of meetings, interchange of information and discussions between experts from different organizations. Europa Nostra, the leading Cultural Heritage organization in Europe, supported this project through the participation of qualified experts that volunteered for the realization of the assessment of the site during 2016 and experts from EIB Institute have drafted this report. The project The Ererouyk site, identified as one of the “7 Most Endangered Sites” of Europe in 2016, is situated to the North West of Yerevan on a rocky plateau next to the Akhourian River. -

The Cathedral of Ani, Turkey from Church to Monument

chapter 25 The Cathedral of Ani, Turkey From Church to Monument Heghnar Z. Watenpaugh* Located on a remote triangular plateau overlook- by a ‘historic partnership’ between the Ministry ing a ravine that separates Turkey and Armenia, and the World Monuments Fund, and partially the medieval ghost city of Ani was once a cul- financed by the us Department of State’s Amba- tural and commercial center on the Silk Road ssadors Fund.2 These high-profile government (Figures 25.1, 25.2). Now, it is the largest cultural initiatives occur at a time of unprecedented heritage site in Eastern Turkey. Ani boasts a diverse deliberation within Turkish civil society about the range of extraordinary ruins—ramparts, churches, country’s foundation and modern history. Indeed, mosques, palaces, and rock-carved dwellings, built an ongoing and contested debate has questioned over centuries by successive Christian and Muslim the tenets of official Turkish historiography, such dynasties. However, its most celebrated monu- as the idea of the monolithic nature of Turkish ments are Armenian churches from the tenth to identity; it has rediscovered the religious and eth- the thirteenth centuries. Ani is inextricably linked nic diversity of Turkish society; and has sought to to this Armenian Christian layer, a sense captured uncover and acknowledge repressed episodes of by its medieval name, ‘The City of 1001 Churches.’ the twentieth century, focusing in particular on Ani’s Cathedral is arguably the site’s most iconic the destruction of the Armenian communities of structure, the one most endowed with world archi- Anatolia through genocide. While the Ministry’s tectural importance (Figure 25.3). -

Matean Ołbergut‛Ean – Das „Buch Der Klagelieder“

Matean ołbergut‛ean – das „Buch der Klagelieder“ Eine Konzeption aus der Klosterschule von Narek als eine Praktik der kulturellen Selbstverortung in dem sich transformierenden armenischen Kulturraum des 10. und 11. Jahrhunderts Dissertation zur Erlangung des philosophischen Doktorgrades an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Georg-August-Universität zu Göttingen vorgelegt von Mekhak Ayvazyan aus Jerewan (Armenien) Göttingen 2011 Inhaltsverzeichnis I. Einleitung................................................................................................................. 4 1. Zum „Buch der Klagelieder“ .................................................................................... 7 2. Reproduktion der Handschriften ............................................................................ 11 3. Forschungsstand zur Klosterschule von Narek ...................................................... 17 4. Methodische Orientierung ...................................................................................... 20 II. Formierung und Transformation des politischen und religiösen Feldes ....... 31 1. Fundierung der politischen Ordnung ...................................................................... 31 2. Transformation, Spannungsfelder, Grenzmarkierungen ........................................ 58 3. Konfessionelle Asymmetrien ................................................................................. 70 4. Antihäretische Diskursorganisation ....................................................................... 77 5. Positionsbestimmung -

Nte Nn E Au Moyen Age

APERÇU $ U R L'ARCHITECTURE A R M É NTE NN E AU MOYEN AGE orné de 62 illustrations dont 8 en couleurs: par A. ORAK 53 INGÉNIEUR cIVIL U.R. ROME ÉDITÉ PAR LES "AMIS DE LA CULTURE ARMÉNIENNE " LE CAIRE, 1951. -ati IL A ÉTÉ IMPRIMÉ DE CETTE BROCHURE, 2.600 EXEMPLAIRES EN ARABE, ANGLAIS, FRANÇAIS ET ARMÉNIEN, DONT 100 EXEM- PLAIRES DE LUXE EN ARMÉNIEN, SUR PAPIER EXTRA, NUMÉROTÉS DE 1 À 100. A PE R Ç U s U R L'ARCHITECTURE A R M É NI E N N E A U MOYEN AGE orné de 62 illustrations dont 8 en couleurs par A. ORAK INGÉNIEUR CIVIL U. R. R O ME " " ÉoIté rar uEs AMIS DE LA CULTURE ARMÉNIENNE -LE CATRE, 1951. Cette brochure a été publiée à l'occasion de l'EXPOSITION D'ARCHITECTURE ARMÉNIENNE placée SOUS LE HAUT PATRONAGE DE S.E. TAHA HUSSEIN PACHA MINISTRE DE L'INSTRUCTION PUBLIQUE L'exposition organisée par les "Amis de la Culture Arménienne" a 'eu lieu au Caire du 15 au 29 Avril 1951, dans le "Finney Hall de la Société Orientale de Publicité. AMIS DE LA CULTURE ARMÉNIENNE Membres d'honneur : Mme. Neçurs Bourros-GnaL PACHA Mr. JANIG CHAKER Comité directeur : YERVANT DRENTZ-MARCARIAN, Président ALEXANDRE SAROUKAAN, Vice-Président ONNIG AvÉDISSIAN, Secrétaire honoraire Garoz Gocantan, Trésorier ARDACHÈS -ORAKIAN, Conseiller Membres : DICRAN-ANTRANIKIAN Dr. Y. KHATANASSIAN EUGÈNE PAPASIAN -ARSÈNE YERGATIA L APERÇU SUR L'ARCHITECTURE ARMÉNIENNE " "' AU MOYEN AGE (du Ye au MifimeHêlle ) par A. ORAK Lorsqu'en l'an 313, le Christianisme fut reconnu religion d'état dans l'Empire Romain, l'Eglise Arménienne comptait déjà 25 années d'existence, sa reconnaissance officielle par l'Etat Arménien remontant à l'an 288. -

Stereotomy and the Mediterranean: Notes Toward an Architectural History*

STEREOTOMY AND THE MEDITERRANEAN: * NOTES TOWARD AN ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY SARA GALLETTI DUKE UNIVERSITY Abstract Stereotomy, the art of cutting stones into particular shapes for the construction of vaulted structures, is an ancient art that has been practiced over a wide chronological and geographical span, from Hellenistic Greece to contemporary Apulia and across the Mediterranean Basin. Yet the history of ancient and medieval stereotomy is little understood, and nineteenth- century theories about the art’s Syrian origins, its introduction into Europe via France and the crusaders, and the intrinsic Frenchness of medieval stereotomy are still largely accepted. In this essay, I question these theories with the help of a work-in-progress database and database-driven maps that consolidate evidence of stereotomic practice from the third century BCE through the eleventh century CE and across the Mediterranean region. I argue that the history of stereotomy is far more complex than what historians have assumed so far and that, for the most part, it has yet to be written. Key Words Stereotomy, stone vaulting, applied geometry, history of construction techniques. * I am very grateful to John Jeffries Martin and Jörn Karhausen for reading drafts of this essay and providing important suggestions. I am also indebted to the faculty and students of the Centre Chastel (INHA, Paris), where I presented an early version of this essay in April 2016, for helping me clarify aspects of my research. Philippe Cabrit, a maître tailleur of the Compagnons du devoir de France, helped me immensely by generously sharing his knowledge of the practice of stereotomy. This essay is dedicated to Maître Cabrit as a token of my gratitude.