Southern Anthropologist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

ORDEM CRONOLÓGICA: 1ª Star Trek: the Original Series (1966-1969

ORDEM CRONOLÓGICA: 1ª Star Trek: The Original Series (1966-1969) 2ª Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1993) 3ª Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-1999) 4ª Star Trek: Voyager (1995-2001) 5ª Star Trek: Enterprise (2001-2005) Jornada nas Estrelas: A Série Original (NCC-1701) Temporada 1 (1966-1967) 01. The Cage (1964) (A Jaula) -02. Where No Man Has Gone Before (1965) (Onde Nenhum Homem Jamais Esteve) 03. The Corbomite Maneuver (O Ardil Corbomite) 04. Mudds Women (As Mulheres de Mudd) 05. The Enemy Within (O Inimigo Interior) 06. The Man Trap (O Sal da Terra) 07. The Naked Time (Tempo de Nudez) 08. Charlie X (O Estranho Charlie) 09. Balance of Terror (O Equilíbrio do Terror) 10. What Are Little Girls Made Of? (E as Meninas, de que São Feitas?) 11. Dagger of the Mind (O Punhal Imaginário) 12. Miri (Miri) 13. The Conscience of the King (A Consciência do Rei) 14. The Galileo Seven (O Primeiro Comando) -15. Court Martial (Corte Marcial) 16. The Menagerie, Parts I & II (A Coleção, Partes I & II) 17. Shore Leave (A Licença) 18. The Squire of Gothos (O Senhor de Gothos) -19. Arena (Arena) 20. The Alternative Factor (O Fator Alternativo) 21. Tomorrow Is Yesterday (Amanhã é Ontem) 22. The Return of the Archons (A Hora Rubra) 23. A Taste of Armageddon (Um Gosto de Armagedon) 24. Space Seed (Semente do Espaço) 25. This Side of Paradise (Deste Lado do Paraíso) 26. The Devil in the Dark (Demônio da Escuridão) 27. Errand of Mercy (Missão de Misericórdia) 28. The City on the Edge of Forever (Cidade à Beira da Eternidade) 29. -

STAR TREK® on DVD

STAR TREK® on DVD Prod. Season/ Box/ Prod. Season/ Box/ Title Title # Year Disc # Year Disc All Our Yesterdays 78 3/1969 3/6, 39 Man Trap, The 06 1/1966 1/1, 3 Alternative Factor, The 20 1/1967 1/7, 10 Mark of Gideon, The 72 3/1969 3/4, 36 Amok Time 34 2/1967 2/1, 17 Menagerie, The, Part I 16 1/1966 1/3, 8 And the Children Shall Lead 60 3/1968 3/1, 30 Menagerie, The, Part II 16 1/1966 1/3, 8 Apple, The 38 2/1967 2/2, 19 Metamorphosis 31 2/1967 2/3, 16 Arena 19 1/1967 1/5, 10 Miri 12 1/1966 1/2, 6 Assignment: Earth 55 2/1968 2/7, 28 Mirror, Mirror 39 2/1967 2/1, 20 Balance of Terror 09 1/1966 1/4, 4 Mudd's Women 04 1/1966 1/2, 2 Bread and Circuses 43 2/1968 2/7, 22 Naked Time, The 07 1/1966 1/1, 3 By Any Other Name 50 2/1968 2/6, 25 Obsession 47 2/1967 2/4, 24 Cage, The 01\99 0/19641),1988\1986 3/7, 40 Omega Glory, The 54 2/1968 2/6, 27 Catspaw 30 2/1967 2/2, 15 Operation: Annihilate! 29 1/1967 1/8, 15 Changeling, The 37 2/1967 2/1, 19 Paradise Syndrome, The 58 3/1968 3/1, 29 Charlie X 08 1/1966 1/1, 4 Patterns of Force 52 2/1968 2/6, 26 City on the Edge of Forever, The 28 1/1967 1/7, 14 Piece of the Action, A 49 2/1968 2/5, 25 Cloud Minders, The 74 3/1969 3/6, 37 Plato's Stepchildren 67 3/1968 3/3, 34 Conscience of the King, The 13 1/1966 1/4, 6 Private Little War, A 45 2/1968 2/5, 23 Corbomite Maneuver, The 03 1/1966 1/3, 1 Requiem for Methuselah 76 3/1969 3/5, 38 Court Martial 15 1/1967 1/5, 7 Return of the Archons, The 22 1/1967 1/6, 11 Dagger of the Mind 11 1/1966 1/3, 5 Return to Tomorrow 51 2/1968 2/5, 26 Day of the Dove 66 3/1968 -

''Star Trek: the Original Series'': Season 3

''Star Trek: The Original Series'': Season 3 PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 13 Mar 2014 18:19:48 UTC Contents Articles Season Overview 1 Star Trek: The Original Series (season 3) 1 1968–69 Episodes 5 Spock's Brain 5 The Enterprise Incident 8 The Paradise Syndrome 12 And the Children Shall Lead 16 Is There in Truth No Beauty? 19 Spectre of the Gun 22 Day of the Dove 25 For the World Is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky 28 The Tholian Web 32 Plato's Stepchildren 35 Wink of an Eye 38 The Empath 41 Elaan of Troyius 44 Whom Gods Destroy 47 Let That Be Your Last Battlefield 50 The Mark of Gideon 53 That Which Survives 56 The Lights of Zetar 58 Requiem for Methuselah 61 The Way to Eden 64 The Cloud Minders 68 The Savage Curtain 71 All Our Yesterdays 74 Turnabout Intruder 77 References Article Sources and Contributors 81 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 83 Article Licenses License 84 1 Season Overview Star Trek: The Original Series (season 3) Star Trek: The Original Series (season 3) Country of origin United States No. of episodes 24 Broadcast Original channel NBC Original run September 20, 1968 – June 3, 1969 Home video release DVD release Region 1 December 14, 2004 (Original) November 18, 2008 (Remastered) Region 2 December 6, 2004 (Original) April 27, 2009 (Remastered) Blu-ray Disc release Region A December 15, 2009 Region B March 22, 2010 Season chronology ← Previous Season 2 Next → — List of Star Trek: The Original Series episodes The third and final season of the original Star Trek aired Fridays at 10:00-11:00 pm (EST) on NBC from September 20, 1968 to March 14, 1969. -

TOS Archives and Inscriptions Trading Cards Checklist

Star Trek: TOS Archives and Inscriptions Trading Cards Checklist Base Cards (Up to 36 variations/quotes per character/base card) # Card Title [ ] 01 Captain Kirk [ ] 02 Spock [ ] 03 Dr. McCoy [ ] 04 Lt. Uhura [ ] 05 Scotty [ ] 06 Lt. Sulu [ ] 07 Ensign Chekov [ ] 08 Nurse Christine Chapel [ ] 09 Yeoman Janice Rand [ ] 10 Captain Pike in The Cage [ ] 11 The Keeper in The Cage [ ] 12 Vina in The Cage [ ] 13 Lt. Cmdr. Gary Mitchell in Where No Man Has Gone Before [ ] 14 Dr. Elizabeth Dehner in Where No Man Has Gone Before [ ] 15 Eve McHuron in Mudd's Women [ ] 16 Balok/Puppet in The Corbomite Maneuver [ ] 17 Lt. Dave Bailey in The Corbomite Maneuver [ ] 18 Charlie Evans in Charlie X [ ] 19 Romulan Commander in Balance of Terror [ ] 20 Andrea in What Are Little Girls Made Of? [ ] 21 Roger Korby in What Are Little Girls Made Of? [ ] 22 Dr. Tristan Adams in Dagger of the Mind [ ] 23 Dr. Helen Noel in Dagger of the Mind [ ] 24 Miri in Miri [ ] 25 Jahn in Miri [ ] 26 Anton Karidian in The Conscience of the King [ ] 27 Lenore Karidian in The Conscience of the King [ ] 28 Lt. Areel Shaw in Court Martial [ ] 29 Samuel T. Cogley in Court Martial [ ] 30 Commodore Jose Mendez in The Menagerie, Parts I and II [ ] 31 Finnegan in Shore Leave [ ] 32 Trelane in The Squire of Gothos [ ] 33 Gorn Captain in Arena [ ] 34 Lazarus in The Alternative Factor [ ] 35 Captain Christopher in Tomorrow Is Yesterday [ ] 36 Mea 3 in A Taste of Armageddon [ ] 37 Anan 7 in A Taste of Armageddon [ ] 38 Khan Noonien Singh in Space Seed [ ] 39 Leila Kalomi in This Side of Paradise [ ] 40 Elias Sandoval in This Side of Paradise [ ] 41 Kor in Errand of Mercy [ ] 42 Ayelborne in Errand of Mercy [ ] 43 Edith Keeler in The City on the Edge of Forever [ ] 44 Sylvia in Catspaw [ ] 45 Korob in Catspaw [ ] 46 Zefram Cochrane in Metamorphosis [ ] 47 Commissioner Nancy Hedford in Metamorphosis [ ] 48 Kras in Friday's Child [ ] 49 Eleen in Friday's Child [ ] 50 Apollo in Who Mourns for Adonais? [ ] 51 Lt. -

2014 Star Trek TOS Portfolio Prints Checklist Base Cards # Card Title

2014 Star Trek TOS Portfolio Prints Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 The Cage [ ] 02 Where No Man Has Gone Before [ ] 03 The Corbomite Maneuver [ ] 04 Mudd's Women [ ] 05 The Enemy Within [ ] 06 The Man Trap [ ] 07 The Naked Time [ ] 08 Charlie X [ ] 09 Balance of Terror [ ] 10 What Are Little Girls Made Of? [ ] 11 Dagger of the Mind [ ] 12 Miri [ ] 13 The Conscience of the King [ ] 14 The Galileo Seven [ ] 15 Court Martial [ ] 16 The Menagerie, Part 1 [ ] 17 The Menagerie, Part 2 [ ] 18 Shore Leave [ ] 19 The Squire of Gothos [ ] 20 Arena [ ] 21 The Alternative Factor [ ] 22 Tomorrow is Yesterday [ ] 23 The Return of the Archons [ ] 24 A Taste of Armageddon [ ] 25 Space Seed [ ] 26 This Side of Paradise [ ] 27 The Devil in the Dark [ ] 28 Errand of Mercy [ ] 29 The City on the Edge of Forever [ ] 30 Operation -- Annihilate! [ ] 31 Catspaw [ ] 32 Metamorphosis [ ] 33 Friday's Child [ ] 34 Who Mourns for Adonais? [ ] 35 Amok Time [ ] 36 The Doomsday Machine [ ] 37 Wolf in The Fold [ ] 38 The Changeling [ ] 39 The Apple [ ] 40 Mirror, Mirror [ ] 41 The Deadly Years [ ] 42 I, Mudd [ ] 43 The Trouble With Tribbles [ ] 44 Bread and Circuses [ ] 45 Journey to Babel [ ] 46 A Private Little War [ ] 47 The Gamesters of Triskelion [ ] 48 Obsession [ ] 49 The Immunity Syndrome [ ] 50 A Piece of the Action [ ] 51 By Any Other Name [ ] 52 Return to Tomorrow [ ] 53 Patterns of Force [ ] 54 The Ultimate Computer [ ] 55 The Omega Glory [ ] 56 Assignment: Earth [ ] 57 Spectre of the Gun [ ] 58 Elaan of Troyius [ ] 59 The Paradise Syndrome [ ] 60 The Enterprise Incident [ ] 61 And the Children Shall Lead [ ] 62 Spock's Brain [ ] 63 Is There in Truth No Beauty? [ ] 64 The Empath [ ] 65 The Tholian Web [ ] 66 For the World is Hollow…. -

Robert H. Justman Collection of Star Trek Television Series Scripts, 1966-1968

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf038n99s7 No online items Finding Aid for the Robert H. Justman Collection of Star Trek Television Series Scripts, 1966-1968 Processed by Arts Library-Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill; Arts Library-Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 89 1 Finding Aid for the Robert H. Justman Collection of Star Trek Television Series scripts, 1966-1968 Collection number: 89 UCLA Arts Library-Special Collections Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: Art Library-Special Collections staff Date Completed: Unknown Encoded by: D.MacGill © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Robert H. Justman Collection of Star Trek Television Series Scripts, Date (inclusive): 1966-1968 Collection number: 89 Origination: Justman, Robert H. Extent: 8 boxes (3.4 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Shelf location: Held at SRLF. Please contact the Performing Arts Special Collections for paging information. -

We Have Never Been Star Trek Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 9-8-2016 We Have Never Been Star Trek Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Sight & Sound (September 8, 2016). Permalink. © 2016 British Film Institute. Used with permission. We have never been Star Trek If not even Star Trek can live up to the Star Trek Ideal, what hope for the race that made it? Gerry Canavan 8 September 2016 1. Star Trek turns 50 today, and a few months after that I will turn 37, the age my father was in 1987 the night Star Trek: The Next Generation premiered. We watched that first episode together, and then every new episode after, through the end of TNG in 1994 and well into the Deep Space Nine and Voyager years, until I left for college in 1998. As a kid, I’d watched scattered The Original Series reruns, as well as The Animated Series reruns that aired weekends on Nickelodeon, but TNG-era Trek was the real start of my fandom of the franchise and the part of it I think I’ll always hold dearest. There was, and is, just something special about it; I don’t know that I can really say precisely what it is. Somehow Trek has just stuck with me, even as – like for so many other people who deeply love this franchise – I seem to have spent most of my time as a fan talking with other fans about how I thought the incompetent showrunners and idiot corporate suits were completely screwing the entire thing up. -

Paved with the Best Intentions? Utopian Spaces in Star Trek, the Original Series (NBC, 1966-1969)

TV/Series 2 | 2012 Les séries télévisées dans le monde : Échanges, déplacements et transpositions ... Paved with the Best Intentions? Utopian Spaces in Star Trek, the Original Series (NBC, 1966-1969) Donna Spalding Andréolle Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/1376 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.1376 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Donna Spalding Andréolle, « ... Paved with the Best Intentions? Utopian Spaces in Star Trek, the Original Series (NBC, 1966-1969) », TV/Series [Online], 2 | 2012, Online since 01 November 2012, connection on 20 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/1376 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.1376 TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. ... Paved with the Best Intentions? Utopian Spaces in Star Trek, the Original Series (NBC, 1966-1969) Donna SPALDING ANDRÉOLLE This paper is an examination of the ways in which the science fiction series Star Trek of the 1960s sheds light on a crucial moment in American history, the social context of which includes political turmoil and the questioning of mainstream values. The very structure of the episodes, often introduced by the captain’s log giving a stardate and a summary of the current situation of the starship Enterprise’s mission-in-progress, points to the exploratory traditions of the American nation built over an almost 300-year period of westward expansion. It is possible, then, to draw a parallel between the Enterprise’s journeys through the universe in search of “strange new planets and civilizations” (dixit Kirk’s voice in the credit scene) and the American quest for new lands needed to perpetuate the utopian project of democratic society first set into motion by the Puritans of New England in the 17th century. -

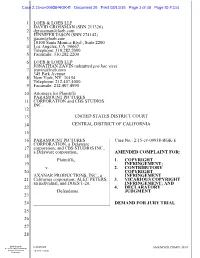

AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR: 18 Plaintiffs, 1

Case 2:15-cv-09938-RGK-E Document 26 Filed 03/11/16 Page 1 of 48 Page ID #:114 1 LOEB & LOEB LLP DAVID GROSSMAN (SBN 211326) 2 [email protected] JENNIFER JASON (SBN 274142) 3 [email protected] 10100 Santa Monica Blvd., Suite 2200 4 Los Angeles, CA 90067 Telephone: 310.282.2000 5 Facsimile: 310.282.2200 6 LOEB & LOEB LLP JONATHAN ZAVIN (admitted pro hac vice) 7 [email protected] 345 Park Avenue 8 New York, NY 10154 Telephone: 212.407.4000 9 Facsimile: 212.407.4990 10 Attorneys for Plaintiffs PARAMOUNT PICTURES 11 CORPORATION and CBS STUDIOS INC. 12 13 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 14 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 15 16 PARAMOUNT PICTURES Case No.: 2:15-cv-09938-RGK-E CORPORATION, a Delaware 17 corporation; and CBS STUDIOS INC., a Delaware corporation, AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR: 18 Plaintiffs, 1. COPYRIGHT 19 INFRINGEMENT; v. 2. CONTRIBUTORY 20 COPYRIGHT AXANAR PRODUCTIONS, INC., a INFRINGEMENT 21 California corporation; ALEC PETERS, 3. VICARIOUS COPYRIGHT an individual, and DOES 1-20, INFRINGEMENT; AND 22 4. DECLARATORY Defendants. JUDGMENT 23 24 DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL 25 26 27 28 Loeb & Loeb LA2480428 A Limited Liability Partnership AMENDED COMPLAINT Including Professional 202828-10048 Corporations Case 2:15-cv-09938-RGK-E Document 26 Filed 03/11/16 Page 2 of 48 Page ID #:115 1 Plaintiffs Paramount Pictures Corporation (“Paramount”) and CBS Studios 2 Inc. (“CBS”) (collectively, “Plaintiffs”), by their attorneys, hereby bring this 3 complaint against Axanar Productions, Inc. (“Axanar Productions”), Alec Peters 4 (“Peters”), and Does 1-20 (collectively, “Defendants”), and allege as follows: 5 NATURE OF THE ACTION 6 1. -

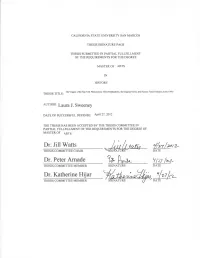

?R A,"T 2Lzar. THESIS COMMITTEE MEMBER SIGNATURE DATE Dr

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY SAN MARCOS THESIS SIGNATTIRE PAGE THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OT THE REQUIRXMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTEROF ARTS IN HISTORY The Origins ofthe Sta Trck Phenomaoa: Gme Roddaber4y, tie Origiml Ssieg and Science Fiction Sandom in the 1960s THESIS TITLE: AUTHOR; LaUra J. Sweeney DATE OF SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE: Apri127,2012 THE THESIS HAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE THESIS COMMITTEE IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FORTHE DEGREE OF MASTEROF ARTS Dr. Jill Vflatts y'/"2/-,2 THESIS COMMITTEE CHAIR oArp Dr. Peter Arnade ?r A,"t 2lzAr. THESIS COMMITTEE MEMBER SIGNATURE DATE Dr. Katherine Hrjar rfzt l,- I THESIS COMMITTEE MEMBER DATE The Origins of the Star Trek Phenomenon: Gene Roddenberry, the Original Series, and Science Fiction Fandom in the 1960s Laura J. Sweeney Department of History California State University San Marcos © 2012 Dedication Mom, you are the only one that has been there for me through thick and thin consistently in my life. Without you, I would not have been able to attend graduate school and write this thesis. Thank you for all your support. I love you always. iii Acknowledgements There are so many wonderful people to thank for making this thesis possible. When I was researching graduate schools, I found California State University San Marcos History Department fascinating and I was overjoyed to be accepted. Yet, I had no idea what it would truly be like and still felt apprehensive on taking a chance. Many chances I took in life did not turn out so well, but this time I was incredibly blessed with good fortune. -

Star Trek: the Original Series

STAR TREK: THE ORIGINAL SERIES List of Episodes in Production Order STAR TREK: THE ORIGINAL SERIES Production Order Airdate Order Season 1 01 The Cage 80 02 Where No Man Has Gone Before 03 03 The Corbomite Maneuver 10 04 Mudd’s Women 06 05 The Enemy Within 05 06 The Man Trap 01 07 The Naked Time 04 08 Charlie X 02 09 Balance of Terror 14 10 What Are Little Girls Made Of? 07 11 Dagger of the Mind 09 12 Miri 08 13 The Conscience of the King 13 14 The Galileo Seven 16 15 Court Martial 20 16 The Menagerie, Pt. I 11 17 The Menagerie, Pt. II 12 18 Shore Leave 15 19 The Squire of Gothos 17 20 Arena 18 21 The Alternative Factor 27 22 Tomorrow is Yesterday 19 23 The Return of the Archons 21 24 A Taste of Armageddon 23 25 Space Seed 22 26 This Side of Paradise 24 27 The Devil in the Dark 25 28 Errand of Mercy 26 29 The City on the Edge of Forever 28 30 Operation: Annihilate! 29 Season 2 31 Catspaw 36 32 Metamorphosis 38 33 Friday's Child 40 34 Who Mourns for Adonais? 31 35 Amok Time 30 36 The Doomsday Machine 35 37 Wolf in the Fold 43 38 The Changeling 32 39 The Apple 34 40 Mirror, Mirror 33 41 The Deadly Years 41 42 I, Mudd 37 43 The Trouble With Tribbles 44 44 Bread and Circuses 54 45 Journey to Babel 39 46 A Private Little War 48 47 The Gamesters of Triskelion 45 48 Obsession 42 49 The Immunity Syndrome 47 50 A Piece of the Action 46 51 By Any Other Name 51 52 Return to Tomorrow 49 53 Patterns of Force 50 54 The Ultimate Computer 53 55 The Omega Glory 52 56 Assignment: Earth 55 Season 3 57 Spectre of the Gun 61 58 Elaan of Troyius 68 59 The