Appropriation of the Spaces of Caste in Sindhi Short

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Sindh Flood Response 2011 FINAL REPORT

Sindh Flood Response 2011 FINAL REPORT (OCT 18, 2011 – FEB 29, 2012) AID-OFDA-G-12-00003 Funded by: United States Agency for International Development Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance USAID/OFDA Organization: Mercy Corps Date: May 31, 2011 HQ Address: 45 SW Ankeny St Portland, OR, 97204, USA USA Pakistan Peter O'Farrell Steve Claborne, Country Director Senior Program Officer, South Asia Tel: (92) 300-501-2340 Tel.: (1) 503-896-5849 E-mail : [email protected] Fax: (1) 503-896-5013 House #36, Street #1, F/6-3 Email: [email protected] Islamabad, Pakistan Country/Region: Pakistan, Districts Badin and Mirpur Khas in Southern Sindh. Mercy Corps, Pakistan ͳ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The monsoon rains that started in the second week of August 2011 triggered serious flooding affecting more than 5.3 million people. It is reported to have destroyed or damaged nearly one million houses and inundated 4.2 million acres of cropland, prompting the Government of Pakistan to call for support from the United Nations. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) for Sindh mobilized its resources relatively quickly, however their response was far too limited compared with the needs of so many people. During the contingency planning phase, they estimated resources adequate to the temporary care of some 50,000 IDPs. The situation had worsened nearly a month after the start of the emergency and the national authorities requested international support. At that point, the NDMA and PDMA indicated that between 5.3 million flood-affected people of Lower Sindh were in urgent need of assistance. -

Final Merit List of Candidates Applied for Admission in Bs Medical Laboratory

BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION - 2020-2021 FINAL MERIT LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR ADMISSION IN BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION 2020-2021 LIAQUAT UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES, JAMSHORO DISTRICT - BADIN (BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) - 01 - SEAT - MERIT) Test Test Int. Total Merit Inter A / Level Test Form No. Name of Candidates Fathers Name Surname Gender DOB District Seat Marks 50% score Positon Obt 50% Year Inter% Grade No. Marks 1 4841 Habesh Kumar Veero Mal Khattri Male 1/11/2001 BADIN 2019 905 82.273 A1 719 82 41 41.136 82.136 District: BADIN - WAITING Menghwar 1496 Akash Kumar Mansingh Male 10/16/2001 BADIN 2020 913 83 A1 167 78 39 41.5 80.5 2 Bhatti 3 1215 Janvi Papoo Kumar Lohana Female 2/11/2002 BADIN 2020 863 78.455 A 894 82 41 39.227 80.227 4 3344 Bushra Muhammad Ayoub Kamboh Female 9/30/2000 BADIN 2019 835 75.909 A 490 82 41 37.955 78.955 5 1161 Chanderkant Papoo Kumar Lohana Male 3/8/2003 BADIN 2020 889 80.818 A1 503 76 38 40.409 78.409 6 3479 Bushra Amjad Amjad Ali Jat Female 4/20/2001 BADIN 2019 848 77.091 A 494 73 36.5 38.545 75.045 7 4306 Noor Ahmed Ghulam Muhammad Notkani Male 10/12/2001 BADIN 2020 874 79.455 A 1575 70 35 39.727 74.727 Muhammad Talha 2779 Hasan Nasir Rajput Male 7/21/2001 BADIN 2020 927 84.273 A1 1378 65 32.5 42.136 74.636 8 Nasir 9 3249 Vandna Dev Anand Lohana Female 3/21/2002 BADIN 2020 924 84 A1 2294 65 32.5 42 74.5 10 2231 Sanjai Eshwar Kumar Luhano Male 8/17/2000 BADIN 2020 864 78.546 A 1939 70 35 39.273 74.273 RANA RAJINDAR 3771 RANA AMAR -

Caste, Materiality and Embodiment: Questioning the Idealism/ Materialism Debate

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 200–216 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.123 Caste, Materiality and Embodiment: Questioning the Idealism/ Materialism Debate Subro Saha1 (Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2019) Abstract Exploring the contingencies and paradoxes shaping the idealism/materialism separation in absolutist terms, this paper attempts to analyze the problems of such separatist tendencies in terms of dealing with the question of caste. Engaging with the problems of separating ‘idea’ and ‘matter’ in relation to the three dominant aspects that shape the conceptualisation of caste—origin(s), body, and society—the paper presents caste as an enmeshed idea-matter embrace that gains its circulation in practice through embodiment. Aiming to counter caste with its own logic and internal contradictions, the paper further proceeds to show that these three aspects that had otherwise been seen for a long time as shaping caste also contradict their own efficacy and logic. With such an approach the paper presents caste as a ghost that feeds on our embodied ideas. Further, bringing in the trope of (mis)reading, the paper tries to examine the intricacies haunting any attempt to deal with the ghost. The paper therefore, can be seen as a humble effort at reminding the necessity of reading the idea of caste in its spectralities and continuous figurations. Keywords Caste, idealism, materiality, touch, embodiment Introduction Despite all diverse attempts to get rid of caste, its persistence reminds us continuously of its haunting spectrality that even after so much beating refuses to die.1 It haunts us like a ghost whose origin and functional modalities continue to baffle us with its shifting trajectories and (trans)formative capacities, and thus continuously challenges our approaches to exorcise it. -

Origin and Development of Urdu Language in the Sub- Continent: Contribution of Early Sufia and Mushaikh

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 27, No. 1, January-June 2012, pp.141-169 Origin and Development of Urdu Language in the Sub- Continent: Contribution of Early Sufia and Mushaikh Muhammad Sohail University of the Punjab, Lahore ABSTRACT The arrival of the Muslims in the sub-continent of Indo-Pakistan was a remarkable incident of the History of sub-continent. It influenced almost all departments of the social life of the people. The Muslims had a marvelous contribution in their culture and civilization including architecture, painting and calligraphy, book-illustration, music and even dancing. The Hindus had no interest in history and biography and Muslims had always taken interest in life-history, biographical literature and political-history. Therefore they had an excellent contribution in this field also. However their most significant contribution is the bestowal of Urdu language. Although the Muslims came to the sub-continent in three capacities, as traders or business men, as commanders and soldiers or conquerors and as Sufis and masha’ikhs who performed the responsibilities of preaching, but the role of the Sufis and mash‘iskhs in the evolving and development of Urdu is the most significant. The objective of this paper is to briefly review their role in this connection. KEY WORDS: Urdu language, Sufia and Mashaikh, India, Culture and civilization, genres of literature Introduction The Muslim entered in India as conquerors with the conquests of Muhammad Bin Qasim in 94 AH / 712 AD. Their arrival caused revolutionary changes in culture, civilization and mode of life of India. -

Tando Muhammad Khan

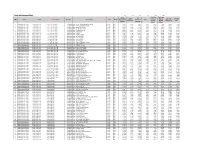

Tando Muhammad Khan 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010002 GBPS - YAR M. KANDRA@PIR BUX KANDRA Primary Boys 9,117 1,823 7,294 1,823 1,823 7,294 29,175 7,294 2 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010016 GBPS - YAR MUHAMMAD KANDRA Primary Boys 11,323 2,265 9,058 2,265 2,265 9,058 36,233 9,058 3 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010017 GBPS - KHUDA BUX GUMB Primary Boys 14,353 2,871 11,482 2,871 2,871 11,482 45,929 11,482 4 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010022 GBPS - ALAM KHAN TALPUR Primary Boys 44,542 8,908 35,634 8,908 8,908 35,634 142,535 35,634 5 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010025 GBPS - PALIO GHUMRANI Primary Boys 28,220 5,644 22,576 5,644 5,644 22,576 90,303 22,576 6 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010026 GBPS - KARIMABAD Primary Boys 28,690 5,738 22,952 5,738 5,738 22,952 91,808 22,952 7 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

Historical Sketch of Peasant Activism: Tracing Emancipatory Political Strategies of Peasant Activists of Sindh

International Journal Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN (P): 2319-393X; ISSN(E): 2319-3948 Vol. 3, Issue 5, Sep 2014, 23-42 © IASET HISTORICAL SKETCH OF PEASANT ACTIVISM: TRACING EMANCIPATORY POLITICAL STRATEGIES OF PEASANT ACTIVISTS OF SINDH GHULAM HUSSAIN 1 & ANWAAR MOHYUDDIN 2 1MPhil Scholar, Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 2 Lecturer, Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan ABSTRACT Peasant activism in Sindh is very diverse and has its own typical history. Temporally, it has been focused on contextual issues that demand more than just land reforms. Peasant activists have, over the years, pursued roughly articulated, expedient and highly diverse agendas that are enacted by the mix of civil society activists, NGOs and ethnic peasant activists. In this article, which is the result of ethnographic study and the analysis of secondary ethnographic and historical data, effort has been made to trace the formation of peasantivist agendas and strategies in Sindh, particularly tracing it from the peasant struggle of Shah Inayat in 17 th century. The introduction of exploitative Batai system during British rule, the consequent institutionalization of sharecropping, establishment of Hari Committee in 1930s, the launching of Batai Tehreek and Elati Tehreek have been traced in relation to shifting peasantivist agendas. Failure of peasant activists to bring about substantive land reforms and the recent process of NGO-ising of peasant activism, have been analyzed vis-à-vis historical past. KEYWORDS: Peasant Activism, Peasant Movements, N.G.Os INTRODUCTION In this study the genesis of exploitation in peasant communities of Sindh has been elaborated, and the historical analysis of some of the important peasant struggles, rebels, and movements have been done to understand where peasants and peasant activist in Sindh stands now. -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

![[Jan-Mar.'2006] Awareness / Disclosure](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0740/jan-mar-2006-awareness-disclosure-680740.webp)

[Jan-Mar.'2006] Awareness / Disclosure

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PREFACE The report in hand is the Final (updated October 2006) of the Integrated Social & Environmental Assessment (ISEA) for proposed Water Sector Improvement Project (WSIP). This report encompasses the research, investigations, analysis and conclusions of a study carried out by Mls Osmani & Co. (Pvt.) Ltd., Consulting Engineers for the Institutional Reforms Consultant (IRC) of Sindh Irrigation & Drainage Authority (SIDA). The Proposed Water Sector Improvement Project (WSIP) Phase-I, being negotiated between Government of Sindh and the World Bank entails a number of interventions aimed at improving the water management and institutional reforms in the province of Sindh. The second largest province in Pakistan, Sindh has approx. 5.0 Million Ha of farm area irrigated through three barrages and 14 canals. The canal command areas of Sindh are planned to be converted into 14 Area Water Boards (AWBs) whereby the management, operations and maintenance would be carried out by elected bodies. Similarly the distributaries and watercourses are to be managed by Farmers Organizations (FOs) and Watercourse Associations (WCAs), respectively. The Project focuses on the three established Area Water Boards (AWBs) of Nara, Left Bank (Akram Wah & Phuleli Canal) & Ghotki Feeder. The major project interventions include the following targets:- * Improvement of 9 main canals (726 Km) and 37 branch canals (1,441 Km). This includes new lining of 50% length of the lined reach of Akram Wah. * Control of Direct Outlets * Replacement of APMs with agreed type of modules * Improvement of 173 distributaries and minor canals ( 1527 Krn) including 145 Km of geomembrane lining and 1 12 Km of concrete lining in 3 AWBs. -

Paninian Studies

The University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies MICHIGAN PAPERS ON SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA Ann Arbor, Michigan STUDIES Professor S. D. Joshi Felicitation Volume edited by Madhav M. Deshpande Saroja Bhate CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Number 37 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress catalog card number: 90-86276 ISBN: 0-89148-064-1 (cloth) ISBN: 0-89148-065-X (paper) Copyright © 1991 Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-064-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-89148-065-5 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12773-3 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90169-2 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ CONTENTS Preface vii Madhav M. Deshpande Interpreting Vakyapadiya 2.486 Historically (Part 3) 1 Ashok Aklujkar Vimsati Padani . Trimsat . Catvarimsat 49 Pandit V. B. Bhagwat Vyanjana as Reflected in the Formal Structure 55 of Language Saroja Bhate On Pasya Mrgo Dhavati 65 Gopikamohan Bhattacharya Panini and the Veda Reconsidered 75 Johannes Bronkhorst On Panini, Sakalya, Vedic Dialects and Vedic 123 Exegetical Traditions George Cardona The Syntactic Role of Adhi- in the Paninian 135 Karaka-System Achyutananda Dash Panini 7.2.15 (Yasya Vibhasa): A Reconsideration 161 Madhav M. Deshpande On Identifying the Conceptual Restructuring of 177 Passive as Ergative in Indo-Aryan Peter Edwin Hook A Note on Panini 3.1.26, Varttika 8 201 Daniel H. -

Faculty of Juridical Sciences

FACULTY OF JURIDICAL SCIENCES COURSE:BALLB Semester –IV SUBJECT: SOCIOLOGY-III SUBJECT CODE:BAL-401 NAME OF FACULTY: DR.SHIV KUMAR TRIPATHI Lecture-21 Varna (Hinduism) Varṇa (Sanskrit: व셍ण, romanized: varṇa), a Sanskrit word with several meanings including type, order, colour or class,[1][2] was used to refer to social classes in Hindu texts like the Manusmriti.[1][3][4] These and other Hindu texts classified the society in principle into four varnas:[1][5] Brahmins: priests, scholars and teachers. Kshatriyas: rulers, warriors and administrators. [6] Vaishyas: agriculturalists and merchants. Shudras: laborers and service providers. Communities which belong to one of the four varnas or classes are called savarna or "caste Hindus". The Dalits and tribes who do not belong to any varna were called avarna.[7][8] This quadruple division is a form of social stratification, quite different from the more nuanced system Jātis which correspond to the European term "caste".[9] The varna system is discussed in Hindu texts, and understood as idealised human callings.[10][11] The concept is generally traced to the Purusha Sukta verse of the Rig Veda. The commentary on the Varna system in the Manusmriti is oft-cited.[12] Counter to these textual classifications, many Hindu texts and doctrines question and disagree with the Varna system of social classification.[13] Etymology and origins The Sanskrit term varna is derived from the root vṛ, meaning "to cover, to envelop, count, classify consider, describe or choose" (compare vṛtra).[14] The word appears -

Controlled Growth of Zinc Oxide Nanowire Arrays by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) Method

IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.19 No.8, August 2019 135 Controlled Growth of Zinc Oxide Nanowire Arrays by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) Method Waseem A. Bhutto1, Abdul Majid Soomro1, Altaf H. Nizamani1, Hussain Saleem2*, Murad Ali Khaskheli1, Ali Ghulam Sahito3, Roshan Das1, Usman Ali Khan1, Samina Saleem2,4 1Institute of Physics, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan. 2Department of Computer Science, UBIT, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan. 3Centre for Pure & Applied Geology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan. 4Karachi University Business School, KUBS, University of Karachi, Pakistan. *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract The Nanostructured materials like nanotubes, nanowires, sensors [11], Resistive-switching Random Access Memory nanorods, and nanobelts etc. have remained the subject of interest (RRAM) [12][13], nano-generators [14][15], nano- these days because of its unique thermal, mechanical and optical capacitors [16], and gas sensors [17][18]. properties. Zinc Oxide (푍푛푂), is the most attractive material due to its unique properties and availability of a variety of growth The performance of 푍푛푂 based devices strongly depend methods. At nanostructured level, the properties of 푍푛푂 can be on their dimensions and morphologies [19][20][21][22][23] altered by controlling the growth process, such as the shape, size, [24][25][26]. Therefore, the investigation of 푍푛푂 nano- morphology, aspect ratio and density control. In this work, structures in highly oriented, aligned and ordered arrays is of Aligned 푍푛푂 Nanowires (NWs) were successfully synthesized by critical importance for the development of novel devices. Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) on Aluminum doped Zinc Different methods have been used to synthesize 푍푛푂 Oxide (AZO) substrate.