B'telem Report: "Expel and Exploit: the Israeli Practice of Taking Over

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

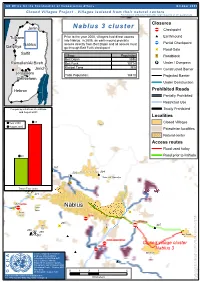

Nablus 3 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) Nablus 3 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm Prior to the year 2000, villagers had direct access Earthmound into Nablus. In 2005, an earthmound prohibits ¬Ç Nablus access directly from Beit Dajan and all access must Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya go through Beit Furik checkpoint D Road Gate Salfit Village Population /" Roadblock Beit Dajan 3696 Ramallah/Al Bireh Beit Furik 10714 º¹P Under / Overpass Jericho Khirbet Tana N/A Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 14410 Projected Barrier Bethlehem Under Construction Hebron Prohibited Roads Partially ProhibitedTubas Restricted Use Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited ## and August 2005 Tubas Burqa Localities 45 Closed Villages Year 2000 Yasid August 2005 Beit Imrin Palestinian localities Natural center Nisf Jubeil Access routes Sabastiya Ijnisinya Road used today 290 # 358#20Shave Shomeron Road prior to Intifada ¬Ç An Naqura 287 ## 389 'Asira ash Shamaliya 294 # 293 # ## ## 288¬Ç beit iba 'Asira ash Shamaliya /" Qusin Travel Time (min) 271 D 270Ç SARRA Nablus D ¬ Sarra Sarra Sarra D Sarra ¬Ç At Tur 279 beit furik cp the of part the 265 D ÇÇ 297 Tell ¬¬ delimitation the concerning # Tell # 269 ## ## 296## 268 ## # Beit Dajan 266#267 ## awarta commercial cp ¬Ç Closed village cluster ¬Ç huwwara Nablus 3 ## Closure mapping is a work in Beit Furik progress. Closure data is collected by OCHA field staff and is subject to change. ## Maps will be updated regularly. Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian Information Centre - October 2005 Base data: 03612 O C H A O C H OCHA update August 2005 For comments contact <[email protected]> Tel. -

Privatizing Religion: the Transformation of Israel's

Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious- Zionist community BY Yair ETTINGER The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Author 2 Acknowlegements 3 Introduction 4 The Religious Zionist tribe 5 Bennett, the Jewish Home, and religious privatization 7 New disputes 10 Implications 12 Conclusion: The Bennett era 14 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious-Zionist community The Author air Ettinger has served as a journalist with Haaretz since 1997. His work primarily fo- cuses on the internal dynamics and process- Yes within Haredi communities. Previously, he cov- ered issues relating to Palestinian citizens of Israel and was a foreign affairs correspondent in Paris. Et- tinger studied Middle Eastern affairs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is currently writing a book on Jewish Modern Orthodoxy. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — the Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — The Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Index More Information Index 1948 Arab–Israeli War, the, 2 Ariel, Uri, 76, 116 1949 Armistice Agreements, the, 2 Arutz Sheva, 120–121, 154, 205 1956 Sinai campaign, the, 60 Ashkenazi, 42, 64, 200 1979 peace agreement, the, 57 Association for Retired People, 23 Australia, 138 Abrams, Eliott, 59 Aviner, Shlomo, 65, 115, 212 Academic Council for National, the. See Professors for a Strong Israel B’Sheva, 120 action B’Tselem, 36, 122 connective, 26 Barak, Ehud, 50–51, 95, 98, 147, 235 extreme, 16 Bar-Ilan University, 50, 187 radical, 16 Bar-Siman-Tov, Yaacov, 194, 216 tactical, 34 Bat Ayin Underground, the, 159 activism BDS. See Boycott, Divestment and moderate, 15–16 Sanctions transnational, 30–31 Begin, Manahem, 47, 48, 118–119, Adelson, Sheldon, 179, 190 157, 172 Airbnb, 136 Beit El, 105 Al Aqsa Mosque, the, 146 Beit HaArava, 45 Al-Aqsa Intifada. See the Second Intifada Beitar Illit, 67, 70, 99 Alfei Menashe, 100 Beitar Ironi Ariel, 170 Allon, Yigal, 45–46 Belafonte, Harry, 14 Alon Shvut, 88, 190 Ben Ari, Michael, 184 Aloni, Shulamit, 182 Bendaña, Alejandro, 24 Altshuler, Amos, 189 Ben-Gurion, David, 46 Amana, 76–77, 89, 113, 148, 153–154, 201 Ben-Gvir, Itamar, 184 American Friends of Ariel, 179–180 Benn, Menachem, 164 American Studies Association, 136 Bennett, Naftali, 76, 116, 140, 148, Amnesty International, 24 153, 190 Amona, 79, 83, 153, 157, 162, 250, Benvenisti, Meron, 1 251 Ben-Zimra, Gadi, 205 Amrousi, Emily, 67, 84 Ben-Zion, -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

Ultraorthodox Jews in Israel – Epidemic As a Measure of Challenges Marek Matusiak

OSW Commentary CENTRE FOR EASTERN STUDIES NUMBER 341 23.06.2020 www.osw.waw.pl Ultraorthodox Jews in Israel – epidemic as a measure of challenges Marek Matusiak In Israel as in other countries, when the COVID-19 epidemic surfaced it exacerbated the existing divi- sions and tensions in society. A group that came under severe attack from the public was the Jewish Ultraorthodox population (the Haredi). This was due to disregard on the part of certain ultraorthodox groups of the restrictions imposed in response to the epidemic and an exceptionally high infection rate in that community – as much as 70% of cases recorded from February until May this year affected members of that community.1 This non-conformity with the regulations by some Haredi (in fact a distinct minority) resonated broadly because it was an element of a decades-long heated dispute over the state’s approach towards the group and its place in Israeli society. Over the years, the issue has repeatedly caused severe shockwaves (including collapse of government coalitions). The stance adopted by the Haredi during the initial phase of the epidemic provided critics of the Haredi with new arguments that they are de facto a law unto themselves, and as a result are becoming increasingly socially and politically problematic. While COVID-19 cannot be expected to significantly change the subjects under debate, the arguments used in the debate, or the balance of power, it will make the dispute even more complex than before the epidemic and lead to greater polarisation. This will further complicate Israel’s efforts to meet challenges posed by the rapid increase in the community’s population. -

Nablus Salfit Tubas Tulkarem

Iktaba Al 'Attara Siris Jaba' (Jenin) Tulkarem Kafr Rumman Silat adh DhahrAl Fandaqumiya Tubas Kashda 'Izbat Abu Khameis 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza 'Izbat al Khilal Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid Kafa El Far'a Camp Al Hafasa Beit Imrin Ramin Ras al Far'a 'Izbat Shufa Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil Wadi al Far'a Tammun Sabastiya Shufa Ijnisinya Talluza Khirbet 'Atuf An Naqura Saffarin Beit Lid Al Badhan Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Kafr Sur Qusin Zawata Khirbet Tall al Ghar An Nassariya Beit Iba Shida wa Hamlan Kur 'Ein Beit el Ma Camp Beit Hasan Beit Wazan Ein Shibli Kafr ZibadKafr 'Abbush Al Juneid 'Azmut Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jit Sarra Salim Furush Beit Dajan Baqat al HatabHajja Tell 'Iraq Burin Balata Camp 'Izbat Abu Hamada Kafr Qallil Beit Dajan Al Funduq ImmatinFar'ata Rujeib Madama Burin Kafr Laqif Jinsafut Beit Furik 'Azzun 'Asira al Qibliya 'Awarta Yanun Wadi Qana 'Urif Khirbet Tana Kafr Thulth Huwwara Odala 'Einabus Ar Rajman Beita Zeita Jamma'in Ad Dawa Jafa an Nan Deir Istiya Jamma'in Sanniriya Qarawat Bani Hassan Aqraba Za'tara (Nablus) Osarin Kifl Haris Qira Biddya Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Talfit Qusra Salfit As Sawiya Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Bani Zeid 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Sinjil Turmus'ayya. -

Initial Analysis of the Israeli Supreme Court's Decision in the Settlements Regularization Law Case

Initial Analysis of the Israeli Supreme Court's Decision in the Settlements Regularization Law Case HCJ 1308/17, Silwad Municipality, et al. v. The Knesset, et. al Issued 15 June 2020 On 9 June 2020, the Israeli Supreme Court decided in an 8 to 1 judgment to cancel the "Settlements Regularization Law for Judea and Samaria [the West Bank]".1 In a ruling spanning 107 pages, the court found that the law violates the rights of Palestinians to property, equality and dignity disproportionately.2 The Knesset passed the controversial law in February 2017. The law provides that the State of Israel could expropriate privately-owned Palestinian land in the occupied West Bank, and to retroactively “regularize” or “legalize” the Israeli settlements built on it. An Addendum to the Law identified 16 settlements to which the law would apply (see Annex at the end of this paper, which also includes a list of the Palestinian villages on which these settlements encroach). According to the court's decision, as of 2016, the scope of Israeli construction on privately-owned Palestinian land in the West Bank amounted to 3,455 structures, of which 1,285 are residential buildings or public institutions.3 The Court’s decision is based on several main legal principles: 1. International law and the non-sovereignty principle applies to the West Bank: The decision stresses that since June 1967, the laws that apply in the West Bank are the laws of "belligerent occupation," supplemented by international human rights law. Further, “the practical implication is that the law of the State of Israel does not apply in the region.”4 1 HCJ 1308/17, Silwad Municipality, et al. -

The Purpose of This Paper Is to Assess Various Unilateral Evacuation

CONFIDENTIAL NOT FOR CIRCULATION MEMORANDUM TO: DR. SAEB ERAKAT FROM: NSU SETTLEMENTS FILE SUBJECT: PRE-PERMANENT STATUS SETTLEMENT EVACUATIONS (PART I): AN ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING PROPOSALS DATE: 30 APRIL 2006 The purpose of this paper is to assess various unilateral evacuation proposals put forth thus far, including Kadima’s “convergence” plan, and their implications for Palestinian interests. I. BACKGROUND Since the evacuation of some 8,500 Israeli settlers from Gaza and four small West Bank settlements as part of Sharon’s unilateral “disengagement” plan, there are growing indications that Israel may seek to carry out further settlement evacuations (as distinct from military withdrawals or redeployments) on a unilateral basis. While a negotiated settlement evacuation remains the preferred strategic option for Palestinians, the growing acceptability of Israeli unilateralism in Israel and abroad suggests that Palestinians may be forced to prepare for the possibility of further disengagement-type evacuations prior to (or instead of) permanent status negotiations, most likely in the context of a “state with provisional borders”. Many in Israel and elsewhere appear to view further unilateral settlement evacuations with increasing favor, particularly if Israeli and/or international confidence in the PA continues to wane. A recent poll shows that a slight majority of Israelis (51%) would favor further unilateral ‘disengagement-type’ evacuations by Israel in the event of the Palestinian leadership’s inability to negotiate or deliver a permanent status deal.1 Indeed, Israeli and international support for unilateralism may now be even higher following Hamas’s recent election victory. A number of unilateral evacuation proposals have already been put forward since the Gaza evacuation, by both the Israeli “left” and “center”. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13864-3 — The Israeli Settler Movement Sivan Hirsch-Hoefler , Cas Mudde Excerpt More Information Introduction Fifty years ago, the State of Israel was able to return to Judea, Samaria and the Jordan Valley. Fifty years have passed, and we are stronger and certainly much more successful. We will have all the international sup- port when we have the confidence. We need to know that this is our land. We will never return to the ‘67 borders. Former Deputy Foreign Minister Tzipi Hotovely (Likud) (Arutz Sheva, March 28, 2017) The Israeli settler movement is not only one of the most enduring social movements in recent history, having been active for over fifty years now, but it is also widely seen as one of the most successful. Observers on both sides of the highly polarized issue of Israel’s politics in the West Bank agree on little, but all accept that the settler movement is one of the most important actors on this issue. For example, Likud member and then- Knesset Speaker Reuven Rivlin, who has served as President of Israel since 2014, has thanked the settlers for keeping Zionism alive (Kikar Hashabat, August 3, 2011), while Labor Party Member of Knesset (the Israeli Parliament) Stav Shaffir has argued that the left-wing camp should learn from the settler movement, because, although accounting for only a tiny percent of the population, they have managed to establish facts on the ground so that the next generation will grow up in a messianic and extremist society (At Magazine, August 1, 2018). -

Inside This Issue

PAM GOLDING ON MAIN NOW LETTING Locate your office in Kenilworth. Peter Golding 082 825 5561 | Teresa Cook 079 527 0348 Office: 021 426 4440 www.pamgolding.co.za/on-main VOLUME 31 No 10 NOVEMBER 2014 /5775 www.cjc.org.za An interview with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu By Shlomo Cesana, Gonen Ginat, and Amos Regev/JNS.org In this interview with Israel Hayom objective, meaning achieving lasting commander and a bad ahead of Rosh Hashanah, Prime peace and quiet by re-establishing commander, is that Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shared deterrence via dealing [Hamas] a massive a good commander his perspective and strategy, and blow. What happens if they try again? They knows how to achieve analysed the changing realities in the will be dealt a doubly debilitating blow — the declared goals for a Middle East. and they know it.” lesser price. We would Why didn’t Israel vanquish Hamas? have ended up with the Israel Hayom: Is Israel doing better or he answer to that question is same result, only with a worse than it was doing on the eve of Rosh “Tvery complex and it entails a much heavier price, and Hashanah last year? variety of considerations. One of those I don’t want to elaborate enjamin Netanyahu: “We are doing considerations is a spatial consideration, further.” Bbetter while facing a harsher reality. which cannot be ignored. We have Hamas How influential was the The reality around us is that radical Islam in the south, al-Qaeda and the Nusra IDF in preventing a wider is marching forward on all fronts. -

West Bank Settlement Homes and Real Estate Occupation

Neoliberal Settlement as Violent State Project: West Bank Settlement Homes and Real Estate Occupation Yael Allweil Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning, Technion and Israel Institute for Advanced Studies [email protected] Abstract Intense ideological debates over the legal status of West Bank settlements and political campaigns objecting to or demanding their removal largely neglect the underlying capitalist processes that construct these settlements. Building upon the rich scholarship on the interrelations of militarism and capitalism, this study explores the relationship between capitalist and militarist occupation through housing development. Pointing to neoliberalism as central to the ways in which militarism and capitalism have played out in Israeli settlement dynamics since 1967, this paper unpacks the mutual dependency of the Israeli settlement project on real estate capitalism and neoliberal governance. Through historical study of the planning, financing, construction, and architecture of settlement dwellings as real estate, as well as interviews and analysis of settler-produced historiographies, this paper identifies the Occupied Territories (OT) as Israel’s testing ground for neoliberal governance and political economy. It presents a complementary historiography for the settlement project, identifying three distinct periods of settlement as the product of housing real estate: neoliberal experimentation (1967-1994), housing militarization (1994-2005), and “real-estate-ization” (2005-present). Drawing on Maron and Shalev -

Violations of Civil and Political Rights in the Realm of Planning and Building in Israel and the Occupied Territories

Violations of Civil and Political Rights in the Realm of Planning and Building in Israel and the Occupied Territories Shadow Report Submitted by Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights Response to the State of Israel’s Report to the United Nations Regarding the Implementation of the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights September 2014 Written by Atty. Sharon Karni-Kohn Edited by Elana Silver and Ma'ayan Turner Contributions by Cesar Yeudkin, Nili Baruch, Sari Kronish, Nir Shalev, Alon Cohen Lifshitz Translated from Hebrew by Jessica Bonn 1 Table of Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….…5 Response to Pars. 44-48 in the State Report: Territorial Application of the Covenant………………………………………………………………………………5 Question 6a: Demolition of Illegal Construstions………………………………...5 Response to Pars. 57-59 in the State Report: House Demolition in the Bedouin Population…………………………………………………………………………....5 Response to Pars. 60-62 in the State Report: House Demolition in East Jerusalem…7 Question 6b: Planning in the Arab Localities…………………………………….8 Response to Pars. 64-77 in the State Report: Outline Plans in Arab Localities in Israel, Infrastructure and Industrial Zones…………………………………………………8 Response to Pars. 78-80 in the State Report: The Eastern Neighborhoods of Jerusalem……………………………………………………………………………10 Question 6c: State of the Unrecognized Bedouin Villages, Means for Halting House Demolitions and Proposed Law for Reaching an Arrangement for Bedouin Localities in the Negev, 2012…………………………………………...15 Response to Pars. 81-88 in the State Report: The Bedouin Population……….…15 Response to Pars. 89-93 in the State Report: Goldberg Commission…………….19 Response to Pars. 94-103 in the State Report: The Bedouin Population in the Negev – Government Decisions 3707 and 3708…………………………………………….19 Response to Par.