Guide to Further Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friedrich Engels in the Age of Digital Capitalism. Introduction

tripleC 19 (1): 1-14, 2021 http://www.triple-c.at Engels@200: Friedrich Engels in the Age of Digital Capitalism. Introduction. Christian Fuchs University of Westminster, [email protected], http://fuchs.uti.at, @fuchschristian Abstract: This piece is the introduction to the special issue “Engels@200: Friedrich Engels in the Age of Digital Capitalism” that the journal tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique published on the occasion of Friedrich Engels’s 200th birthday on 28 November 2020. The introduction introduces Engels’s life and works and gives an overview of the special issue’s contributions. Keywords: Friedrich Engels, 200th birthday, anniversary, digital capitalism, Karl Marx Date of Publication: 28 November 2020 CC-BY-NC-ND: Creative Commons License, 2021. 2 Christian Fuchs 1. Friedrich Engels’s Life Friedrich Engels was born on 28 November 1820 in Barmen, a city in North Rhine- Westphalia, Germany, that has since 1929 formed a district of the city Wuppertal. In the early 19th century, Barmen was one of the most important manufacturing centres in the German-speaking world. He was the child of Elisabeth Franziska Mauritia Engels (1797-1873) and Friedrich Engels senior (1796-1860). The Engels family was part of the capitalist class and operated a business in the cotton manufacturing industry, which was one of the most important industries. In 1837, Engels senior created a business partnership with Peter Ermen called Ermen & Engels. The company operated cotton mills in Manchester (Great Britain) and Engelskirchen (Germany). Other than Marx, Engels did not attend university because his father wanted him to join the family business so that Engels junior already at the age of 16 started an ap- prenticeship in commerce. -

Untitled Remarks from “Köln, 30

Jewish Philosophical Politics in Germany, 1789–1848 the tauber institute series for the study of european jewry Jehuda Reinharz, General Editor Sylvia Fuks Fried, Associate Editor Eugene R. Sheppard, Associate Editor The Tauber Institute Series is dedicated to publishing compelling and innovative approaches to the study of modern European Jewish history, thought, culture, and society. The series features scholarly works related to the Enlightenment, modern Judaism and the struggle for emancipation, the rise of nationalism and the spread of antisemitism, the Holocaust and its aftermath, as well as the contemporary Jewish experience. The series is published under the auspices of the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry— established by a gift to Brandeis University from Dr. Laszlo N. Tauber—and is supported, in part, by the Tauber Foundation and the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com Sven-Erik Rose Jewish Philosophical Politics in Germany, 1789–1848 ChaeRan Y. Freeze and Jay M. Harris, editors Everyday Jewish Life in Imperial Russia: Select Documents, 1772–1914 David N. Myers and Alexander Kaye, editors The Faith of Fallen Jews: Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi and the Writing of Jewish History Federica K. Clementi Holocaust Mothers and Daughters: Family, History, and Trauma *Ulrich Sieg Germany’s Prophet: Paul de Lagarde and the Origins of Modern Antisemitism David G. Roskies and Naomi Diamant Holocaust Literature: A History and Guide *Mordechai -

PHILOSOPHICAL (PRE)OCCUPATIONS and the PROBLEM of IDEALISM: from Ideology to Marx’S Critique of Mental Labor

PHILOSOPHICAL (PRE)OCCUPATIONS AND THE PROBLEM OF IDEALISM: From Ideology to Marx’s Critique of Mental Labor by Ariane Fischer Magister, 1999, Freie Universität Berlin M.A., 2001, The Ohio State University M.Phil., 2005, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2010 Dissertation directed by Andrew Zimmerman Associate Professor of History The Columbian College of The George Washington University certifies that Ariane Fischer has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 25, 2009. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. PHILOSOPHICAL (PRE)OCCUPATIONS AND THE PROBLEM OF IDEALISM: From Ideology to Marx’s Critique of Mental Labor Ariane Fischer Dissertation Research Committee: Andrew Zimmerman, Associate Professor of History, Dissertation Director Peter Caws, University Professor of Philosophy, Committee Member Gail Weiss, Professor of Philosophy, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2010 by Ariane Fischer All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments The author wishes to thank her dissertation advisor Andrew Zimmerman, who has been a continuous source of support and encouragement. His enthusiastic yet demanding guidance has been invaluable. Both his superior knowledge of history and theory as well as his diligence in reviewing drafts have been crucial in the successful completion of the research and writing process. Further, many thanks are extended to Gail Weiss and Peter Caws for joining the dissertation committee, and to Dan Moschenberg and Paul Smith for agreeing to be readers. -

Volume 25, Number 1, Fall 2010 • Marx, Politics… and Punk Roland Boer

Volume 25, Number 1, Fall 2010 • Marx, Politics… and Punk Roland Boer. “Marxism and Eschatology Reconsidered” Mediations 25.1 (Fall 2010) 39-59 www.mediationsjournal.org/articles/marxism-and-eschatology-reconsidered. Marxism and Eschatology Reconsidered Roland Boer Marxism is a secularized Jewish or Christian messianism — how often do we hear that claim? From the time of Nikolai Berdyaev (1937) and Karl Löwith (1949) at least, the claim has grown in authority from countless restatements.1 It has become such a commonplace that as soon as one raises the question of Marxism and religion in a gathering, at least one person will jump at the bait and insist that Marxism is a form of secularized messianism. These proponents argue that Jewish and Christian thought has influenced the Marxist narrative of history, which is but a pale copy of its original: the evils of the present age with its alienation and exploitation (sin) will be overcome by the proletariat (collective redeemer), who will usher in a glorious new age when sin is overcome, the unjust are punished, and the righteous inherit the earth. The argument has served a range of very different purposes since it was first proposed: ammunition in the hands of apostate Marxists like Berdyaev and especially Leszek Kolakowski with his widely influential three-volume work, Main Currents of Marxism;2 a lever to move beyond the perceived inadequacies of Marxism in the hands of Christian theologians eager to assert that theological thought lies at the basis of secular movements like Marxism, however -

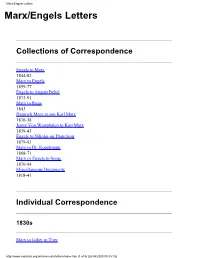

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters

Marx/Engels Letters Marx/Engels Letters Collections of Correspondence Engels to Marx 1844-82 Marx to Engels 1859-77 Engels to August Bebel 1873-91 Marx to Ruge 1843 Heinrich Marx to son Karl Marx 1836-38 Jenny Von Westphalen to Karl Marx 1839-43 Engels to Nikolai-on Danielson 1879-93 Marx to Dr. Kugelmann 1868-71 Marx or Engels to Sorge 1870-94 Miscellaneous Documents 1818-41 Individual Correspondence 1830s Marx to father in Trier http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (1 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters November 10, 1837 1840s Marx to Carl Friedrich Bachman April 6, 1841 Marx to Oscar Ludwig Bernhard Wolf April 7, 1841 Marx to Dagobert Oppenheim August 25, 1841 Marx To Ludwig Feuerbach Oct 3, 1843 Marx To Julius Fröbel Nov 21, 1843 Marx and Arnold Ruge to the editor of the Démocratie Pacifique Dec 12, 1843 Marx to the editor of the Allegemeine Zeitung (Augsburg) Apr 14, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Bornstein Dec 30, 1844 Marx to Heinrich Heine Feb 02, 1845 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Sep 19, 1846 Engels to the communist correspondence committee in Brussels Oct 23, 1846 Marx to Pavel Annenkov Dec 28, 1846 1850s Marx to J. Weydemeyer in New York (Abstract) March 5, 1852 1860s http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/letters/index.htm (2 of 5) [26/08/2000 00:28:15] Marx/Engels Letters Marx to Lasalle January 16, 1861 Marx to S. Meyer April 30, 1867 Marx to Schweitzer On Lassalleanism October 13, 1868 1870s Marx to Beesly On Lyons October 19, 1870 Marx to Leo Frankel and Louis Varlin On the Paris Commune May 13, 1871 Marx to Beesly On the Commune June 12, 1871 Marx to Bolte On struggles witht sects in The International November 23, 1871 Engels to Theodore Cuno On Bakunin and The International January 24, 1872 Marx to Bracke On the Critique to the Gotha Programme written by Marx and Engels May 5, 1875 Engels to P. -

Dialectical Humanism: an Ethic of Self-Actualization

DIALECTICAL HUMANISM: AN ETHIC OF SELF-ACTUALIZATION BY Hernan David Carrillo Submitted to the graduate degree in Philosophy and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________ Chairperson ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Date defended: ______________ The Dissertation Committee for Hernan David Carrillo certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: DIALECTICAL HUMANISM: AN ETHIC OF SELF-ACTUALIZATION Committee: _____________________________ Chairperson _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ Date approved: _________________________ ii Abstract In the history of western philosophy, few thinkers have managed to generate as much controversy and confusion as Karl Marx. One issue caught in this controversy and mired in confusion the presence of evaluative language in Marx’s ‘later’ works. Critics have seized on its presence, contending that it contradicts his theory of history, rendering his critique of political economy nothing more than proletarian ideology. These criticisms are based on an inconsistency that is only apparent. As this dissertation will demonstrate, Marx is able to consistently and objectively combine evaluation and description in his ‘later’ works because embedded within his dialectical method is an ethic of self-actualization I call Dialectical Humanism. Since so much of the confusion surrounding this issue stems from a failure to adequately contextualize it, Chapter I places Marx’s life and thought in proper perspective. With the overview of the development of Marx’s life and thought complete, Chapter II examines his theory of history to understand how it explains socio-historical phenomena. Chapter III elucidates Marx’s humanism, tracing its development from an explicit to an implicit aspect of his thought. -

Becoming Max Stirner

BECOMING MAX STIRNER Most of what is known about the person who became “Max Stirner” was discovered and collected in the late nineteenth century by his biographer, the Scottish-German novelist, poet, and anarchist writer John Henry Mackay. Mackay laments in his biography that very little is known about Max Stirner. Mackay regrets that he was able to gather only the “bare facts” about Stirner’s life, especially before the publication of The Ego alld Its Own. Mackay reports that many of his efforts to uncover the facts about Stirner’s life, beyond the “mere statistics” and “dead numbers,” were frustrated by the absence of pertinent documents and lack of cooperation from certain principals, specifically, Stirner’s second wife Marie Dahnhardt. “Max Stirner” was actually the pen name, or the nom de guerre, of a German schoolteacher named Johann Caspar Schmidt. Schmidt acquired the nickname “Stirner” as student because of his high forehead, which was accentuated by the manner in which he parted his hair. “Max Stirner” was a humorous, but affectionate moniker because it translates into “Max the Highbrow.” Schmidt was born in the Bavarian town of Bayreuth on November 6, 1806, to Albert Christian Heinrich Schmidt, a flute maker and part-time portrait painter, and Sophia Eleonora Schmidt. 1806 was a year of considerable social disorganization in Bayreuth and the entirety of West Prussia because of the Napoleonic Wars. 1806 was the last year of Prussian rule, which was replaced by the domination of Napoleon. Schmidt’s parents were likely married in 1805 and had no other children. -

The Discreet Charm of the Petty Bourgeoisie: Marx, Proudhon, and the Critique of Political Economy

The Discreet Charm of the Petty Bourgeoisie: Marx, Proudhon, and the Critique of Political Economy by Ryan Breeden B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2018 Associate of Arts, Douglas College, 2016 Thesis SuBmitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Ryan Breeden 2020 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2020 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Ryan Breeden Degree: Master of Arts Thesis title: The Discreet Charm of the Petty Bourgeoisie: Marx, Proudhon, and the Critique of Political Economy Committee: Chair: Thomas Kuehn Associate Professor, History Mark Leier Supervisor Professor, History Roxanne Panchasi Committee Member Associate Professor, History Stephen Collis Examiner Professor, English ii Abstract This thesis examines Marx and Engels’s concept of the petty Bourgeoisie and its application to the French socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Rather than treating the concept as purely derogatory, I show that for Marx and Engels, the petty bourgeoisie was crucial in their Broader critique of political economy By emBodying the contradiction between capital and labour. Because of their structural position between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, the petty bourgeoisie are economically, politically, and socially pulled in two separate directions––identifying with either the owners of property, with propertyless workers, or with both simultaneously. This analysis is then extended by investigating Marx’s critique of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. I argue that for Marx, Proudhon was not wrong Because he was a memBer of the petty Bourgeoisie. -

Rescuing the Individual from Neoliberalism: Education, Anarchism, and Subjectivity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Educational Policy Studies Dissertations Department of Educational Policy Studies Spring 5-11-2018 Rescuing the Individual from Neoliberalism: Education, Anarchism, and Subjectivity Gabriel Keehn Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss Recommended Citation Keehn, Gabriel, "Rescuing the Individual from Neoliberalism: Education, Anarchism, and Subjectivity." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2018. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss/178 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Educational Policy Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Educational Policy Studies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, RESCUING THE INDIVIDUAL FROM NEOLIBERALISM: EDUCATION, ANARCHISM, AND SUBJECTIVITY, by GABRIEL T. KEEHN, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Philosophy, in the College of Education and Human Development, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chairperson, as representatives of the faculty certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. __________________________ Deron Boyles, Ph.D. Committee Chair __________________________ __________________________ Kristen Buras, Ph.D. Chara Bohan, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member __________________________ __________________________ Judith Suissa, Ph.D. Michael Bruner, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member __________________________ Date __________________________ William Curlette, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Educational Policy Studies __________________________ Paul A. -

Roland's Heading 1

ISSN 1556-3723 (print) Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion __________________________________________________________________ Volume 6 2010 Article 2 __________________________________________________________________ Revelation and Revolution: Friedrich Engels and the Apocalypse Roland Boer* Research Professor School of Humanities and Social Science University of Newcastle New South Wales, Australia * [email protected] Copyright © 2010 Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion is freely available on the World Wide Web at http://www.religjournal.com. Revelation and Revolution: Friedrich Engels and the Apocalypse Roland Boer Research Professor School of Humanities and Social Science University of Newcastle New South Wales, Australia Abstract In tracing a relatively unknown but important feature of the work of Friedrich Engels, this article offers a critical commentary on his lifelong engagement with the New Testament book of Revelation. Beginning with material from his late teens, when he was undergoing the long, slow process of giving up his Calvinist faith, Engels used the text for humor and satire, for polemics, and as a way to express his own exuberance. As the years unfolded, he would come to appreciate this biblical book in a very different fashion, namely, as a historical document that offered a win- dow into earliest Christianity. Through three essays, one on Revelation, another on Bruno Bauer (from whom Engels drew increasingly as he grew older), and a third on early Christianity, Engels developed the influential argument that Christianity had revolutionary origins. -

The Young Hegelians and Karl Marx

5-" || AVID MC THE YOUNG HEGELIANS AND KARL MARX David McLellan Essential reading for students of nineteenth-century German thought and of Marxism,this book rediscovers in the Young Hegelian movement the intellectual origins of Marx's thought After an introductory analysis of the secularisation ofthe move ment as its members moved from theological criticism to political opposition, there followsections on the four most prominent radical disciples of Hegel: Bruno Bauer, Feuerbach, Stirner and Hess. Their work is dis cussed in itself and also for its influence on Marx. Inthese sections the background to such questions as the theological origins of Marx’s ideas, his relationship to Hegel and how he came to be primarily interested in economics is discussed. The book makes clear that Marxism is very much a product. albeit an original product, of its time and can only be understood with reference to the intellectual atmosphere in which it was conceived. Fora biographical note on the author see back flap. THE YOUNG l-IEGELIANS AND KARL MARX Also by David McLellan EARLY MARX TEXTS THE YOUNG HEGELIANS AND KARL MARX DAVID McLELLAN University of Kent at Canterbury MACNHLLAN London - Melbourne - Toronto 1969 © David McLellan 1969 Published by MACMILLAN AND co LTD Little Essex Street London w c 2 and also at Bombay Calcutta and Madras Macmillan South Africa (Publishers) Pty Ltd Johannesburg The Alacmillan Company of Australia Pty Ltd Melbourne The Macmillan Company of Canada Ltd Toronto Printed in Great Britain by R. a R. CLARK LTD. Edinburgh TO SIMONE BRASSART CONTENTS PREFACE ix INTRODUCTION 1. The Beginnings of the Hegelian School a. -

Philosophia · 31 ·

PHILOSOPHIA · 31 · DELLO STESSO AUTORE PRESSO LE NOSTRE EDIZIONI Esistenza e progetto. Tra Hegel e Nietzsche L’incompiuto maestro. Metafisica e morale in Schopenhauer e Kant Verità e potere. Oltre il nichilismo del senso del reale Esperienza del tempo. Studio su Hegel FABIO BAZZANI UNICO AL MONDO Studi su Stirner Editrice Clinamen Questo volume è frutto di una ricerca svolta presso il Dipartimento di Lettere e Filosofia dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze e beneficia per la pubblicazione di un contributo a carico dei fondi di ricerca d’Ateneo ex 60%. 1a edizione giugno 2013 © Copyright 2013 Editrice Clinamen Progetto grafico di Norma Tassoni In copertina: rielaborazione dell’opera di Otto Dix, Roter Kopf (1919) Editing e impaginazione: PCS - Servizi per l’editoria ([email protected]) Stampa: RM Print - Firenze ([email protected]) Editrice Clinamen - Firenze, via Cigoli 49 - www.clinamen.it ISBN: 978-88-8410-198-3 INDICE PREFAZIONE 7 INTRODUZIONE 11 1. LO SPIRITO DEL TEMPO E L’ANNICHILIMENTO DELL’INDIVIDUALITÀ 23 2. LA RIVOLTA CONTRO LA METAFISICA 61 3. IL RITORNO DELLA METAFISICA. L’UNIONE DEGLI UNICI 81 4. LA DIFFERENZA 97 5. UN UNICO INEFFABILE 111 6. MORALE E LIBERTÀ DELL’UNICO 131 CONCLUSIONE 141 BIBLIOGRAFIA 159 PREFAZIONE Negazione di tutto ciò che nega l’individualità. Rivolta contro la meta- fisica, non contro una metafisica. Reiezione di un senso universale oltre il reale per come mi appare. Questo “reale” è il mio reale, per come io lo de- termino esser tale, stabilendo in questa mia determinazione ogni reale in coincidenza con il suo apparire medesimo.