Transformational Trademark Law in Cyberspace*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C. T. Geppert FLEETING CITIES Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe Co-Edited EUROPEAN EGO-HISTORIES Historiography and the Self, 1970–2000 ORTE DES OKKULTEN ESPOSIZIONI IN EUROPA TRA OTTO E NOVECENTO Spazi, organizzazione, rappresentazioni ORTSGESPRÄCHE Raum und Kommunikation im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert NEW DANGEROUS LIAISONS Discourses on Europe and Love in the Twentieth Century WUNDER Poetik und Politik des Staunens im 20. Jahrhundert Imagining Outer Space European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century Edited by Alexander C. T. Geppert Emmy Noether Research Group Director Freie Universität Berlin Editorial matter, selection and introduction © Alexander C. T. Geppert 2012 Chapter 6 (by Michael J. Neufeld) © the Smithsonian Institution 2012 All remaining chapters © their respective authors 2012 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. -

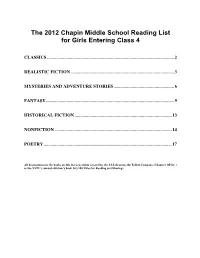

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4 CLASSICS ............................................................................................................... 2 REALISTIC FICTION .......................................................................................... 3 MYSTERIES AND ADVENTURE STORIES ..................................................... 6 FANTASY ................................................................................................................ 9 HISTORICAL FICTION ..................................................................................... 13 NONFICTION ...................................................................................................... 14 POETRY ................................................................................................................ 17 All descriptions for the books on this list were either created by the LS Librarian, the Follett Company (Chapin’s OPAC ) or the NYPL’s annual children’s book list (100 Titles for Reading and Sharing). Classics Aiken, Joan. Wolves of Willoughby Chase. Two young girls are sent to live on an isolated country estate where they find themselves in the clutches of an evil governess. Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Follow the lives of four sisters in nineteenth-century New England. Baum, L. Frank. The Wizard Of Oz. An elegant and rich story about a girl, her friends, and a humbug wizard. Burnett, Frances Hodgson. The Secret Garden. A young orphan named Mary is sent to live at a creepy English estate -

Biography Fantasy, Folklore, Mythology Graphic Historical Novels/Non- Fiction Fiction Non-Fiction Mystery Poetry Realistic Science Fiction Fiction

Grade 5 – Grade 6 Booklist Biography Fantasy, Folklore, Mythology Graphic Historical Novels/Non- Fiction Fiction Non-Fiction Mystery Poetry Realistic Science Fiction Fiction Biography Fleischman, Sid Escape!: The Story of the Great Houdini A biography of the magician, ghost chaser, aviator, and king of escape artists whose amazing feats are remembered long after his death in 1926. Pair this with The Abracadabra Kid: A Writer’s Life by the same author! Freedman, The Adventures of Marco Polo (Read other books by this author) Russell An illustrated chronicle of the travels of thirteenth-century explorer Marco Polo; includes a discussion of the controversy over whether he indeed went to China. Green, Michelle A Strong Right Arm Y. Tells the story of Mamie "Peanut" Johnson, a woman who had to overcome the obstacles of gender and race to pursue her dream of playing baseball, and who finally got her chance when she and other African-American women were invited to play in the Negro Leagues after male players were allowed on major league teams. Kostyal, K. M. Trial by Ice: A Photobiography of Sir Ernest Shackleton Traces the adventurous life of the South Pole explorer whose ship, the Endurance, was frozen in ice and crushed, leaving the captain and crew to fight for survival. Krull, Kathleen Marie Curie Presents a biography of Polish-French physicist and chemist Marie Curie, who was a pioneer in the field of radioactivity and won a Noble prize in both physics and in chemistry. Paulsen, Gary Guts: The True Stories Behind Hatchet and the Brian Books This collection of six stories reveals Paulsen's real-life spirit and the part it played in Brian's four adventures. -

Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators Official Reading List Summer 2016

SOCIETY OF CHILDREN’S BOOK WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS OFFICIAL READING LIST SUMMER 2016 All books are grouped by geographical region of the author or illustrator. They are listed in alphabetical order by title and divided into grade levels. TABLE OF CONTENTS ATLANTIC (Pennsylvania / Delaware / New Jersey / Washington D.C. / Virginia / West Virginia / Maryland) . 3 AUSTRALIA / NEW ZEALAND (May - December 2016) . 15 CALIFORNIA / HAWAII . 21 CANADA . 37 INTERNATIONAL / OTHER . 43 MID-SOUTH (Kansas / Louisiana / Arkansas / Tennessee / Kentucky / Missouri / Mississippi) . 45 MIDDLE EAST / INDIA / ASIA . 51 MIDWEST (Minnesota / Iowa / Nebraska / Wisconsin / Illinois / Michigan / Indiana / Ohio) . 53 NEW ENGLAND (Maine / Vermont / New Hampshire / Connecticut / Massachusetts / Rhode Island) . 69 NEW YORK . 81 SOUTHEAST (Florida / Georgia / South Carolina / North Carolina / Alabama) . 89 SOUTHWEST (Nevada / Arizona / Utah / Colorado / Wyoming / New Mexico) . 99 TEXAS / OKLAHOMA . 107 UK / IRELAND . 113 WEST (Washington / Oregon / Alaska / Idaho / Montana / North Dakota / South Dakota) . 117 SPANISH / BILINGUAL . 127 SOCIETY OF CHILDREN’S BOOK WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS OFFICIAL READING LIST — SUMMER 2016 ATLANTIC (Pennsylvania / Delaware / New Jersey / Washington D.C. / Virginia / West Virginia / Maryland) GRADES K-2: garten beginning readers. Author’s Residence: Reading, Pennsylvania Apple Days: A Rosh Hashanah Story Publisher: Reading Reading Books by Allison Sarnoff Soffer, illustrated by Bob McMahon Picture Book The Boy Who Said Nonsense Description: A touching story about a child’s beloved apple-picking by Felicia Sanzari Chernesky, illustrated by Nicola Anderson tradition, disappointment, and the power of community. Apple- Picture Book sauce recipe included. Description: Tate can count just by looking at things! All this count- Author’s Residence: Washington, D.C. ing makes everyone think Tate talks nonsense—until his brother Publisher: Kar-Ben Publishing sees everything from Tate’s perspective. -

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Reading and activity ideas for your Chatterbooks group About this pack Ahoy, me Hearties – and shiver me timbers! Here be a Chatterbooks pack full of swashbuckling pirate fun – activity ideas and challenges, and great reading for your group! The pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their publisher partnership Children’s Reading Partners Chatterbooks [ www.readinggroups.org/chatterbooks] is a reading group programme for children aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. The Reading Agency is an independent charity working to inspire more people to read more through programmes for adults, young people and Children – including the Summer Reading Challenge, and Chatterbooks. See www.readingagency.org.uk Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Contents 2 Things to talk about 2 Activity ideas 8 Chatterbooks double session plan, with a pirates theme 10 Pirates and perils quiz 11 Pirates and perils: great titles to read 17 More swashbuckling stories For help in planning your Chatterbooks meeting, have a look at these Top Tips for a Successful Session 2 Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Ideas for your Chatterbooks sessions Things to talk about What do you know about pirates? Get together a collection of pirate books – stories and non-fiction – so you’ve got lots to refer to, and plenty of reading for your group to share. -

Slaying Dragons Ebook, Epub

SLAYING DRAGONS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Daniel Kolenda | 224 pages | 07 Jan 2020 | Charisma House | 9781629996578 | English | Lake Mary, United States Slaying Dragons PDF Book But had he ever awoken to the truth, it would have been truly pitiable. We have listed all the details we had about the same. Product image 1. It sees you shrink. I have family members who have also fallen for scams. Bad boy Gentleman thief Pirate Air pirate Space pirate. Like this: Like Loading But our daily battles are part of a much bigger war, and we have been given all we need to win. Notify me of new posts by email. Please enter your name, your email and your question regarding the product in the fields below, and we'll answer you in the next hours. A similar thing befell my uncle. The perspective of meeting people beyond the veil, free from the haze of mortality, resonates with me. I sometimes see my life as slaying dragons. You will falsely think that quitting will bring peace and reprieve, but alas, only regret and disappointment await the quitter. The recurring Crucible event in Destiny 2 , Iron Banner, has returned once again. Then, the real property is sold because of defaulted mortgages or unpaid taxes. Do you believe it? Sigurd overhears two nearby birds discussing the heinous treachery being planned by his companion, Regin. Strings were broken, the tail piece looked awful, the bridge was weird, and the fingerboard was covered in old, brittle tape. Join the conversation There are 6 comments about this story. Add To Cart. -

Pirates and Perils of the Deep Chatterbooks Activity Pack

Pirates and Perils of the Deep Chatterbooks activity pack Pirates and Perils of the Deep About this pack Ahoy, me Hearties – and shiver me timbers! Here be a Chatterbooks pack full of swashbuckling pirate fun – activity ideas and challenges, and great reading for your group! The pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their publisher partnership Children’s Reading Partners Chatterbooks is a reading group programme for children aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. The Reading Agency is an independent charity working to inspire more people to read more through programmes for adults, young people and Children – including the Summer Reading Challenge, and Chatterbooks. See www.readingagency.org.uk Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Contents 2 Things to talk about 2 Activity ideas 8 Chatterbooks double session plan, with a pirates theme 10 Pirates and perils quiz 11 Pirates and perils: great titles to read 17 More swashbuckling stories 2 Pirates and Perils of the Deep Chatterbooks Activity Pack Ideas for your Chatterbooks sessions Things to talk about What do you know about pirates? Get together a collection of pirate books – stories and non-fiction – so you’ve got lots to refer to, and plenty of reading for your group to share. -

Rick Spacey and the Space Detectives

UPDATED: 11/22/2011 RICK SPACEY AND THE SPACE DETECTIVES by S.D GRAUBERT 2 UPDATED: 11/22/2011 Characters: Team Leader - Rick Spacey Female Actor- Page, Hank, Wobbly, Jack Sparrow, Davy Jones Male Actor - Great Frump, Marv, Wobbly, Red Beard OMB song. (Male Actor leaves during song to change.) (GREAT FRUMP sits on the trunk and wails.) GREAT FRUMP Ohhhhhhhhhhh.OhWohhhhhh. (Muttering) Inconsolable, insoncolable, inconsolable. (Loud) that means disconsolate, which means very, very, very UNHAPPY. Ohhhhhhhwohhhh. (She continues) PAGE (Enters SR, with questions) Ahem. GREAT FRUMP Ohhhhhhhwohhhh. Inconsolable, inconsolable, inconsol—(etc). PAGE Ahem. Great Frumpness? GREAT FRUMP Yes, yes? What? PAGE The little Frumps are here to see you, M’am ( or Sir). GREAT FRUMP Can’t you, you know, get rid of them? PAGE They must see you now. They have been waiting. GREAT FRUMP Oh, alright then. Show them in. (PAGE coaches two kids in audience, who read out printed IOUs. Get them to stand up and ask their name. Introduce them to frump and then have them read the questions.) KID You owe me five frumps of gold— GREAT FRUMP 3 UPDATED: 11/22/2011 Five frumps? What on Planet Frump do I owe you five Frumps of gold for? KID For picking up all the leaves. PAGE Very important job, Great Frumpness. Here we have another: KID #2 You owe me ten gold frumps. GREAT FRUMP Ten? What for this time? KID #2 For counting all the stars in the sky. PAGE Very important job, Great Frumpness. How else would we know how many there were? GREAT FRUMP Well, how many are there? KID #2 (Makes up a number) GREAT FRUMP (Asks other kids in audience) And how many gold frumps do you say I owe you? For what? And you? (Continues to ask until) Okay, okay. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Long Way Home

Deep Space D-6 Adventure #1: The Long Way Home Science Fiction Role-Playing Game and Adventure by Tony Go with Illustrations by Ilya Baranovsky For use with Deep Space D-6 solitaire board game Ver. 1.43 1 We Survived. Barely... The shockwave from the last destroyed enemy ship felt more like a lulling nudge than the staccato reverberations that once punctuated the ongoing assault. It was a trap. Though we survived, our warp drive was severely damaged and our systems were left in critical condition. Luckily, we still have the best weapon in the galaxy: our crew. It’s a long way home. With the amount of fuel we have left, there is no choice but to pass through pirate occupied space. Parts of the journey may even take us through uncharted regions. As a member of the United Earths, it is our duty to provide aid wherever it is needed- even if, as it appears, we are the ones in need of assistance... What happens next in the story? It all depends on the choices you make. The Long Way Home is a role playing supplement created for use with the solitaire board game Deep Space D-6. A copy of Deep Space D-6 is required. The Endless Expansion may be added, but is not required. A symbol denotes the use of expansion content. In The Long Way Home players will take control of a single ship and travel between points on a starmap. As you play, you will be asked to make a choice. Your choice may lead to success or disaster! After you make a choice, follow the instructions to see what hap- pens next. -

Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books

ILLINOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. ?·;·w~""r~~I ` "~ '·~~E University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science University of Illinois Press Uio Ier Nc U UI e vs II r, Tutankhamen's._1~ý4- I _ GC ftI By ROBERT SABUDA Illustrated in five colors by the author *'"As in Sabuda's Saint Valentine, this equally arresting five-color picture book appropriates the art of another culture to evoke a specific historical setting....Sabuda neatly distills the history of a celebrated young ruler while offering a visual treat on each page." -Starred, Publishers Weekly "While not much is really known about Tutankhamen, his persona continues to intrigue young and old alike. Here is a book geared toward younger children about this fascinating figure....The unique- ness of this book is in its extraordinary illustrations....For sheer beauty, Sabuda's book is a winner."- School LibraryJournal $15.95 SBE/0-689-31818-9/Ages 6-9 SBE indicates a reinforced hardcover edition. SATHENEUM BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS An imprint of Simon & Schuster Children's Publishing Division OCTOBER 1994 * 35 THE BIG PICTURE It's Perfectly Normal: A Book about Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex, and Sexual Health written by Robie H. Harris; illustrated by Michael Emberley "Most kids wonder about and have lots of questions about sex," the introduction says, and this frank and cheerful book attempts to answer those questions. There are seven sections: Lots of Questions, What Is Sex, Our Bodies, Puberty, Families and Babies, Decisions, and Staying Healthy; within these sections the author ex- plores puberty, sexual feelings, reproduction, contraception, and other topics. -

Captain Harlock CYOA

Space Pirate Captain Harlock CYOA (Jumpchain-Compliant!) With special thanks to Eisenstein! It is the year 2977 AD. For years, mankind has harvested the resources of many planets to sustain itself and made a multitude of scientific achievements. Robots are used to establish farms on other worlds to feed the people of Earth. However, the people of Earth have grown complacent and weak-willed, controlled by a government unwilling to brave the stars. The apathy gripping the world has grown too great, and one man has decided to shake off the government's shackles and claim the endless sea of the stars for his own! His name – is Captain Harlock! He is not alone in space, however – aimed directly towards Earth are the alien species known as the Mazone. In three days, a mysterious black sphere will strike Tokyo, serving as a beacon for the Mazone invasion forces. All the while, the Federation of Earth is content to fritter away its citizens' days with golf games and parties. What will you do with the ten years you spend here? +1000 CP What is your choice, traveler? Section 1: Identity Roll 1d8+20 to determine your age and keep your current gender, or pay 50 CP to choose it within the range. Drop-In [Free] – You've arrived with no memory of your new life here, but that just means nothing to hold you back. The Earth Federation seems to regard you as a citizen, though, so there's that. You may appear anywhere on Earth when you enter this world.