Explorations in the Vitality of the Ludic Object in Contemporary Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C. T. Geppert FLEETING CITIES Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe Co-Edited EUROPEAN EGO-HISTORIES Historiography and the Self, 1970–2000 ORTE DES OKKULTEN ESPOSIZIONI IN EUROPA TRA OTTO E NOVECENTO Spazi, organizzazione, rappresentazioni ORTSGESPRÄCHE Raum und Kommunikation im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert NEW DANGEROUS LIAISONS Discourses on Europe and Love in the Twentieth Century WUNDER Poetik und Politik des Staunens im 20. Jahrhundert Imagining Outer Space European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century Edited by Alexander C. T. Geppert Emmy Noether Research Group Director Freie Universität Berlin Editorial matter, selection and introduction © Alexander C. T. Geppert 2012 Chapter 6 (by Michael J. Neufeld) © the Smithsonian Institution 2012 All remaining chapters © their respective authors 2012 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. -

Against 'Flat Ontologies'

64 Ray Brassier Deleveling: Against ‘Flat Ontologies’ Ray Brassier is associate professor of philosophy at the American University of Beirut. What I am going to present today is a critical discussion of the 65 tenets of so-called ‘flat ontology’. The expression ‘flat onto- logy’ has a complicated genealogy. It was originally coined as a pejorative term for empiricist philosophies of science by Roy Bhaskar in his 1975 book, A Realist Theory of Science. By the late 1990s, it had begun to acquire a positive sense in discus- sions of the work of Deleuze and Guattari. But it only achieved widespread currency in the wake of Manual De Landa’s 2002 book about Deleuze, Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy. More recently, it has been championed by proponents of ‘ob- ject-oriented ontology’ and ‘new materialism’. It is its use by these theorists that I will be discussing today. I will begin by explaining the ‘four theses’ of flat onto- logy, as formulated by Levi Bryant. Bryant is a proponent of ‘object-oriented ontology’, a school of thought founded by Graham Harman. In his 2010 work The Democracy of Objects, Bryant encapsulates flat ontology in the following four theses: Thesis 1: “First, due to the split characteristic of all ob- jects, flat ontology rejects any ontology of transcendence or presence that privileges one sort of entity as the origin of all others and as fully present to itself.” Thesis 2: “Second, […] the world or the universe does not exist. […] [T]here is no super-object that gathers all other ob- jects together in a single, harmonious -

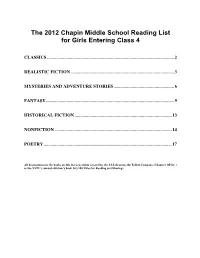

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4 CLASSICS ............................................................................................................... 2 REALISTIC FICTION .......................................................................................... 3 MYSTERIES AND ADVENTURE STORIES ..................................................... 6 FANTASY ................................................................................................................ 9 HISTORICAL FICTION ..................................................................................... 13 NONFICTION ...................................................................................................... 14 POETRY ................................................................................................................ 17 All descriptions for the books on this list were either created by the LS Librarian, the Follett Company (Chapin’s OPAC ) or the NYPL’s annual children’s book list (100 Titles for Reading and Sharing). Classics Aiken, Joan. Wolves of Willoughby Chase. Two young girls are sent to live on an isolated country estate where they find themselves in the clutches of an evil governess. Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Follow the lives of four sisters in nineteenth-century New England. Baum, L. Frank. The Wizard Of Oz. An elegant and rich story about a girl, her friends, and a humbug wizard. Burnett, Frances Hodgson. The Secret Garden. A young orphan named Mary is sent to live at a creepy English estate -

Biography Fantasy, Folklore, Mythology Graphic Historical Novels/Non- Fiction Fiction Non-Fiction Mystery Poetry Realistic Science Fiction Fiction

Grade 5 – Grade 6 Booklist Biography Fantasy, Folklore, Mythology Graphic Historical Novels/Non- Fiction Fiction Non-Fiction Mystery Poetry Realistic Science Fiction Fiction Biography Fleischman, Sid Escape!: The Story of the Great Houdini A biography of the magician, ghost chaser, aviator, and king of escape artists whose amazing feats are remembered long after his death in 1926. Pair this with The Abracadabra Kid: A Writer’s Life by the same author! Freedman, The Adventures of Marco Polo (Read other books by this author) Russell An illustrated chronicle of the travels of thirteenth-century explorer Marco Polo; includes a discussion of the controversy over whether he indeed went to China. Green, Michelle A Strong Right Arm Y. Tells the story of Mamie "Peanut" Johnson, a woman who had to overcome the obstacles of gender and race to pursue her dream of playing baseball, and who finally got her chance when she and other African-American women were invited to play in the Negro Leagues after male players were allowed on major league teams. Kostyal, K. M. Trial by Ice: A Photobiography of Sir Ernest Shackleton Traces the adventurous life of the South Pole explorer whose ship, the Endurance, was frozen in ice and crushed, leaving the captain and crew to fight for survival. Krull, Kathleen Marie Curie Presents a biography of Polish-French physicist and chemist Marie Curie, who was a pioneer in the field of radioactivity and won a Noble prize in both physics and in chemistry. Paulsen, Gary Guts: The True Stories Behind Hatchet and the Brian Books This collection of six stories reveals Paulsen's real-life spirit and the part it played in Brian's four adventures. -

Certificate for Approving the Dissertation

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Kevin J. Rutherford Candidate for the Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Director (Jason Palmeri) Reader (Michele Simmons) Reader (Heidi McKee) Reader (Kate Ronald) Graduate School Representative (Bo Brinkman) ABSTRACT PACK YOUR THINGS AND GO: BRINGING OBJECTS TO THE FORE IN RHETORIC AND COMPOSITION by Kevin J. Rutherford This dissertation project focuses on object-oriented rhetoric (OOR), a perspective that questions the traditional notions of rhetorical action as solely a human province. The project makes three major, interrelated claims: that OOR provides a unique and productive methodology to examine the inclusion of the non-human in rhetorical study; that to some extent, rhetoric has always been interested in the way nonhuman objects interact with humans; and that these claims have profound implications for our activities as teachers and scholars. Chapter one situates OOR within current scholarship in composition and rhetoric, arguing that it can serve as a useful methodology for the field despite rhetoric’s traditional focus on epistemology and human symbolic action. Chapter two examines rhetorical history to demonstrate that a view of rhetoric that includes nonhuman actors is not new, but has often been marginalized. Chapter three examines two videogames as sites of theory and practice for object-oriented rhetoric, specifically focusing on a sense of metaphor to understand the experience of nonhuman rhetors. Chapter four interrogates the network surrounding a review aggregation website to argue that, while some nonhumans may be unhelpful rhetorical collaborators, OOR can assist us in improving relationships with them. -

Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators Official Reading List Summer 2016

SOCIETY OF CHILDREN’S BOOK WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS OFFICIAL READING LIST SUMMER 2016 All books are grouped by geographical region of the author or illustrator. They are listed in alphabetical order by title and divided into grade levels. TABLE OF CONTENTS ATLANTIC (Pennsylvania / Delaware / New Jersey / Washington D.C. / Virginia / West Virginia / Maryland) . 3 AUSTRALIA / NEW ZEALAND (May - December 2016) . 15 CALIFORNIA / HAWAII . 21 CANADA . 37 INTERNATIONAL / OTHER . 43 MID-SOUTH (Kansas / Louisiana / Arkansas / Tennessee / Kentucky / Missouri / Mississippi) . 45 MIDDLE EAST / INDIA / ASIA . 51 MIDWEST (Minnesota / Iowa / Nebraska / Wisconsin / Illinois / Michigan / Indiana / Ohio) . 53 NEW ENGLAND (Maine / Vermont / New Hampshire / Connecticut / Massachusetts / Rhode Island) . 69 NEW YORK . 81 SOUTHEAST (Florida / Georgia / South Carolina / North Carolina / Alabama) . 89 SOUTHWEST (Nevada / Arizona / Utah / Colorado / Wyoming / New Mexico) . 99 TEXAS / OKLAHOMA . 107 UK / IRELAND . 113 WEST (Washington / Oregon / Alaska / Idaho / Montana / North Dakota / South Dakota) . 117 SPANISH / BILINGUAL . 127 SOCIETY OF CHILDREN’S BOOK WRITERS AND ILLUSTRATORS OFFICIAL READING LIST — SUMMER 2016 ATLANTIC (Pennsylvania / Delaware / New Jersey / Washington D.C. / Virginia / West Virginia / Maryland) GRADES K-2: garten beginning readers. Author’s Residence: Reading, Pennsylvania Apple Days: A Rosh Hashanah Story Publisher: Reading Reading Books by Allison Sarnoff Soffer, illustrated by Bob McMahon Picture Book The Boy Who Said Nonsense Description: A touching story about a child’s beloved apple-picking by Felicia Sanzari Chernesky, illustrated by Nicola Anderson tradition, disappointment, and the power of community. Apple- Picture Book sauce recipe included. Description: Tate can count just by looking at things! All this count- Author’s Residence: Washington, D.C. ing makes everyone think Tate talks nonsense—until his brother Publisher: Kar-Ben Publishing sees everything from Tate’s perspective. -

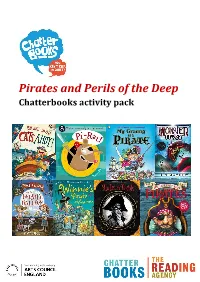

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack

Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Reading and activity ideas for your Chatterbooks group About this pack Ahoy, me Hearties – and shiver me timbers! Here be a Chatterbooks pack full of swashbuckling pirate fun – activity ideas and challenges, and great reading for your group! The pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their publisher partnership Children’s Reading Partners Chatterbooks [ www.readinggroups.org/chatterbooks] is a reading group programme for children aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. The Reading Agency is an independent charity working to inspire more people to read more through programmes for adults, young people and Children – including the Summer Reading Challenge, and Chatterbooks. See www.readingagency.org.uk Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Contents 2 Things to talk about 2 Activity ideas 8 Chatterbooks double session plan, with a pirates theme 10 Pirates and perils quiz 11 Pirates and perils: great titles to read 17 More swashbuckling stories For help in planning your Chatterbooks meeting, have a look at these Top Tips for a Successful Session 2 Pirates and Perils of the Deep! Chatterbooks Activity Pack Ideas for your Chatterbooks sessions Things to talk about What do you know about pirates? Get together a collection of pirate books – stories and non-fiction – so you’ve got lots to refer to, and plenty of reading for your group to share. -

147 Levi R. Bryant. Onto-Cartography: an Ontology Of

Philosophy in Review XXXVI (August 2016), no. 4 Levi R. Bryant. Onto-Cartography: An Ontology of Machines and Media. Edinburgh University Press 2014. 312 pp. $130.00 USD (Hardcover ISBN 9780748679966); $39.95 USD (Paperback ISBN 9780748679973). Levi Bryant characterizes himself as a fervent convert who has recently ‘awoken from [the] dogmatic slumbers’ of historical materialism to produce an anti-humanist political philosophy that dispenses with the ‘discursivism’ and anthropocentrism that has dominated Western philosophy for far too long (4). He has sought to displace the prevailing assumptions of cultural studies and critical theory by crafting a materialist metaphysics that decentralizes humanity and proposes a practice—onto- cartography—that demonstrates how the natural environment shapes our social relations. This new ontological framework, he argues, will allow us to develop more effective strategies for the estab- lishment of justice. The practice of onto-cartography presupposes what Bryant calls a machine-oriented ontol- ogy. Bryant proposes that ‘all beings’, ‘all entities, things, or objects are machines’ (18, 23). According to this model, being consists entirely of machines ‘at a variety of different levels of scale’, from galaxies and social institutions to subatomic particles (6). He broadly defines a machine as any system of operations that takes on inputs and transforms them to produce outputs. So, for example, a tree is a machine that absorbs sunlight and carbon dioxide and, through the process of photosyn- thesis, operates on those inputs to produce oxygen, its output. Moreover, all machines are enmeshed in a fabric of assemblages or a network of machines. An assemblage is a system of relations between ‘coupled’ machines in which particular machinic nodes shape the functioning and development of other machines within the field of relations. -

Slaying Dragons Ebook, Epub

SLAYING DRAGONS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Daniel Kolenda | 224 pages | 07 Jan 2020 | Charisma House | 9781629996578 | English | Lake Mary, United States Slaying Dragons PDF Book But had he ever awoken to the truth, it would have been truly pitiable. We have listed all the details we had about the same. Product image 1. It sees you shrink. I have family members who have also fallen for scams. Bad boy Gentleman thief Pirate Air pirate Space pirate. Like this: Like Loading But our daily battles are part of a much bigger war, and we have been given all we need to win. Notify me of new posts by email. Please enter your name, your email and your question regarding the product in the fields below, and we'll answer you in the next hours. A similar thing befell my uncle. The perspective of meeting people beyond the veil, free from the haze of mortality, resonates with me. I sometimes see my life as slaying dragons. You will falsely think that quitting will bring peace and reprieve, but alas, only regret and disappointment await the quitter. The recurring Crucible event in Destiny 2 , Iron Banner, has returned once again. Then, the real property is sold because of defaulted mortgages or unpaid taxes. Do you believe it? Sigurd overhears two nearby birds discussing the heinous treachery being planned by his companion, Regin. Strings were broken, the tail piece looked awful, the bridge was weird, and the fingerboard was covered in old, brittle tape. Join the conversation There are 6 comments about this story. Add To Cart. -

Degruyter Opphil Opphil-2020-0105 314..334 ++

Open Philosophy 2020; 3: 314–334 Object-Oriented Ontology and Its Critics Graham Harman* The Battle of Objects and Subjects: Concerning Sbriglia and Žižek’s Subject Lessons Anthology https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2020-0105 received April 8, 2020; accepted June 16, 2020 Abstract: This article mounts a defense of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) from various criticisms made in Russell Sbriglia and Slavoj Žižek’sco-edited anthology Subject Lessons. Along with Sbriglia and Žižek’s own Introduction to the volume, the article responds to the chapters by Todd McGowan, Adrian Johnston, and Molly Anne Rothenberg, the three in which my own version of OOO is most frequently discussed. Keywords: Ljubljana School, Object-Oriented Ontology, Slavoj Žižek, G. W. F. Hegel, Jacques Lacan, thing- in-itself, materialism, realism Russell Sbriglia and Slavoj Žižek’sco-edited collection Subject Lessons: Hegel, Lacan, and the Future of Materialism has long been awaited in circles devoted to Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO).¹ All twelve chapters in the anthology (eleven plus the editors’ Introduction) are written from the merciless Lacano- Hegelian standpoint that defines the Ljubljana School, one of the most fruitful trends in the continental philosophy of recent decades.² The Slovenian core of the group is here – Žižek, Mladen Dolar, and Alenka Zupančič – as are many of their most capable international allies (though Joan Copjec is keenly missed), along with some impressive younger voices. As a rule, the book is most impressive when making a positive case for what G. W. F. Hegel and Jacques Lacan still have to offer contemporary philosophy; all of the chapters are clearly written, and some are among the most lucid statements I have seen from the Ljubljana group. -

The Problem: the Theory of Ideas in Ancient Atomism and Gilles Deleuze

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013 The rP oblem: The Theory of Ideas in Ancient Atomism and Gilles Deleuze Ryan J. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Johnson, R. (2013). The rP oblem: The Theory of Ideas in Ancient Atomism and Gilles Deleuze (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/706 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROBLEM: THE THEORY OF IDEAS IN ANCIENT ATOMISM AND GILLES DELEUZE A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College & Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ryan J. Johnson May 2014 Copyright by Ryan J. Johnson 2014 ii THE PROBLEM: THE THEORY OF IDEAS IN ANCIENT ATOMISM AND GILLES DELEUZE By Ryan J. Johnson Approved December 6, 2013 _______________________________ ______________________________ Daniel Selcer, Ph.D Kelly Arenson, Ph.D Associate Professor of Philosophy Assistant Professor of Philosophy (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ______________________________ John Protevi, Ph.D Professor of Philosophy (Committee Member) ______________________________ ______________________________ James Swindal, Ph.D. Ronald Polansky, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College & Graduate Chair, Department of Philosophy School of Liberal Arts Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT THE PROBLEM: THE THEORY OF IDEAS IN ANCIENT ATOMISM AND GILLES DELEUZE By Ryan J. Johnson May 2014 Dissertation supervised by Dr. -

Pirates and Perils of the Deep Chatterbooks Activity Pack

Pirates and Perils of the Deep Chatterbooks activity pack Pirates and Perils of the Deep About this pack Ahoy, me Hearties – and shiver me timbers! Here be a Chatterbooks pack full of swashbuckling pirate fun – activity ideas and challenges, and great reading for your group! The pack is brought to you by The Reading Agency and their publisher partnership Children’s Reading Partners Chatterbooks is a reading group programme for children aged 4 to 14 years. It is coordinated by The Reading Agency and its patron is author Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Chatterbooks groups run in libraries and schools, supporting and inspiring children’s literacy development by encouraging them to have a really good time reading and talking about books. The Reading Agency is an independent charity working to inspire more people to read more through programmes for adults, young people and Children – including the Summer Reading Challenge, and Chatterbooks. See www.readingagency.org.uk Children’s Reading Partners is a national partnership of children’s publishers and libraries working together to bring reading promotions and author events to as many children and young people as possible. Contents 2 Things to talk about 2 Activity ideas 8 Chatterbooks double session plan, with a pirates theme 10 Pirates and perils quiz 11 Pirates and perils: great titles to read 17 More swashbuckling stories 2 Pirates and Perils of the Deep Chatterbooks Activity Pack Ideas for your Chatterbooks sessions Things to talk about What do you know about pirates? Get together a collection of pirate books – stories and non-fiction – so you’ve got lots to refer to, and plenty of reading for your group to share.