1. Morphology Lecture Notes 1.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sandwiches / Sandwiches Salads / Ensaladas Hot Buffet / Bufé Caliente

Sandwiches / Sandwiches Choice of a variety of sandwiches (ham, pate, meat paste, cold sausage, camembert, emmental) 4.80 Sandwich variado a elegir (jamón, paté, chicharrones finos, camembert, Emmental) Mixed sandwich (Ham and emmental cheese) – Sandwich mixto (jamón y Emmental) 7.50 Cantal cheese sandwich – Sandwich de queso Cantal 8.00 Cured ham sandwich – Sandwich de Jamón de país 8.50 Hot dog (sausages, gratinated emmental cheese) – Perrito caliente(salchichas, Emmental gratinado) 12.00 Malakoff sandwich (salad leaves, tomato, egg, ham, mayonnaise) 11.00 Sandwich Malakoff (lechuga, tomate, huevo, jamón, mayonesa) Chaillot sandwich (salad leaves, tomato, egg, poultry meat, mayonnaise) 11.00 Sandwich Chaillot (lechuga, tomate, huevo, ave, mayonesa) Troca sandwich (salad leaves, tomato, egg, tuna, mayonnaise) 11.00 Sandwich Troca (lechuga, tomate, huevo, atún, mayonesa) Classic club sandwich (Bread crumb toasted, tomato, egg, ham, Emmenthal cheese) 12.00 Emparedado Club Clásico (Pan miga toasté, tomate huevo jamón queso gruyère fabricado en Emmenthal) Club sandwich Salmon (Bread crumb toasted, tomato, salmon, guacamole ) 15.00 Emparedado Club Asalmondo (Pan miga toasté, tomate, salmon, guacamole) Plate of chipped potatoes or green salad leaves – Plato de patatas fritas o ensalada 3.80 Salads / Ensaladas Chef’salad (Ham, Emmental cheese, egg) – Ensalada del chef (Jamón, Emmental, huevo) 14.00 Vegetarian Salad (Fresh French beans, fresh mushrooms, artichoke, palm tree heart, sweet corn) 14.50 Ensalada vegetariana (judías verdes frescas, -

Fast-Food Udstyr.Qxd 16-02-2007 09:34 Side 1

Fast-Food Udstyr.qxd 16-02-2007 09:34 Side 1 Fast-Food udstyr Fast-Food Udstyr.qxd 16-02-2007 09:34 Side 3 COOKING EQUIPMENT KOGEUDSTYR KOCHER Pølsekar - Sausage pan - Wurstentöpfe Varenr. Udvendig mål i mm Spænding Max. forbrug Article No. Outside dim. in mm Voltage Total power Art. Nr. Außenmaße in mm Spanning Max. Leistung Højde Bredde Dybde Height Width Depth Höhe Breite Tiefe PK 112 300 250 350 230/400 V 1000/1500 W Tilbehør: Åben ramme. Skydelåg. Hulrist. Skillerum. Accessories: Open frame. Sliding cover. Steaming grid. Divider. PK 112 Zubehör: Offener Rahmen. Schiebedeckel. Dunstrost. Scheidewand. Gasudgave - For bottled gas - Für Propangas: PKG 112 Pølsekar - Sausage pan - Wurstentöpfe Varenr. Udvendig mål i mm Spænding Max. forbrug Article No. Outside dim. in mm Voltage Total power Art. Nr. Außenmaße in mm Spanning Max. Leistung Højde Bredde Dybde Height Width Depth Höhe Breite Tiefe PK 113 300 320 335 230 V 1000 W PK 113 Pølsekar - Sausage pan - Wurstentöpfe Varenr. Udvendig mål i mm Spænding Max. forbrug Article No. Outside dim. in mm Voltage Total power Art. Nr. Außenmaße in mm Spanning Max. Leistung Højde Bredde Dybde Height Width Depth Höhe Breite Tiefe PK 114 300 250 440 230 V 1000 W PK 114 Pølsekar - Sausage pan - Wurstentöpfe Varenr. Udvendig mål i mm Spænding Max. forbrug Article No. Outside dim. in mm Voltage Total power Art. Nr. Außenmaße in mm Spanning Max. Leistung Højde Bredde Dybde Height Width Depth Höhe Breite Tiefe PK 115 300 335 440 230 V 1000 W PK 115 Pølsekar - Sausage pan - Wurstentöpfe Varenr. -

Camp Cooking Tips and Techniques

CAMP COOKING TIPS & TECHNIQUES A collection of information from the internet, from fellow Scouters and originated specifically for this booklet. Wood Badge Ticket Item – Karl Kuegler, Jr. Originally Created January 2008 - Revised & Expanded March 2017 Camp Cooking Tips & Techniques Page 1 Notes: ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ -

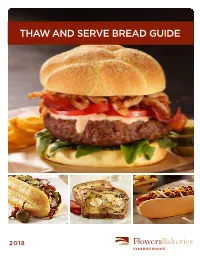

Thaw and Serve Bread Guide

THAW AND SERVE BREAD GUIDE 2018 GREAT BREAD MADE FOR CONVENIENCE At Flowers Bakeries Foodservice, it’s all the little things that make our bread so special. Like the care we take in baking our breads for the best flavor, texture and crumb. It’s also in how we freeze our breads to lock in that “just baked” freshness, the standard by which all great bread is measured. What’s more is we help you choose the right bread products for your signature recipes and stay ahead of the latest culinary trends to keep things exciting. Our hard work and dedication to being the industry’s leading bread expert is all part of our promise to be the only bread partner you’ll ever need. II SUBS & HOAGIES SANDWICH BUNS SANDWICH BREADS MEAL ACCOMPANIMENTS PREMIUM THAW & SERVE BREAD PRODUCTS BREAKFAST BREADS PAGES 2-31 DESSERTS THE VERY BEST IN FROZEN BISCUITS AND READY TO HEAT BISCUITS, GLUTEN FREE OPTIONS FROZEN BISCUIT DOUGH PAGES 32-33 AND GLUTEN FREE MADE WITH CERTIFIED ORGANIC INGREDIENTS PAGES 34-35 ORGANIC BREADS SANDWICH BREADS AND SANDWICH BUNS WHOLE GRAIN BREADS FOR SCHOOLS BISCUITS, ENGLISH MUFFINS PAGES 36-40 AND MEAL ACCOMPANIMENTS 10527420 - TOP SLICED HOT DOG BUN 10599210 - POTATO BUN 10599480 - FRENCH BREAD CREATED FOR FOODSERVICE European Bakers breads are crafted to hold up to the demands of foodservice for the best burgers, sandwiches and paninis in town. ALWAYS SAVE TIME EASY HANDLING & “FIRST DAY” FRESH & MONEY LONG SHELF LIFE Freezing fresh bread stops the Our breads are delivered For first day fresh bread, staling process, so the bread will on the same truck as the rest thaw at room temperature for 12 still taste fresh when it’s thawed. -

Grammar Summary 2Nd Person Ihr Euch Euch 3Rd Person Sie Sie Ihnen Formal Form Sie Sie Ihnen (Singular Or Plural)

DA-01BackGrammar.QXD 6/19/02 12:31 PM Page 387 Personal Pronouns SINGULAR Nominative Accusative Dative 1st person ich mich mir 2nd person du dich dir 3rd person er ihn ihm sie sie ihr es es ihm PLURAL 1st person wir uns uns Grammar Summary 2nd person ihr euch euch 3rd person sie sie ihnen formal form Sie Sie Ihnen (singular or plural) Definite Article Singular Plural Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative der die das die Accusative den die das die Dative dem der dem den Question Words: Wer? Was? Nominative wer was Accusative wen was Dative wem Indefinite Article Singular Plural Masculine Feminine Neuter Nominative ein eine ein keine Accusative einen eine ein keine Dative einem einer einem keinen Grammar Summary 387 DA-01BackGrammar.QXD 6/19/02 12:32 PM Page 388 Regular Verb Forms — Present Tense gehen finden heißen ich gehe finde heiße du gehst findest heißt er, sie, es geht findet heißt wir gehen finden heißen ihr geht findet heißt sie, Sie gehen finden heißen Irregular Verb Forms — Present Tense haben sein wissen ich habe bin weiß du hast bist weißt er, sie, es hat ist weiß wir haben sind wissen ihr habt seid wisst sie, Sie haben sind wissen Command Forms Familiar Geh! Warte! Sei! Hab! (singular) Familiar Geht! Wartet! Seid! Habt! (plural) Formal Gehen Sie! Warten Sie! Seien Sie! Haben Sie! (singular/plural) Wir-form Gehen wir! Warten wir! Seien wir! Haben wir! (Let’s...) 388 Grammar Summary DA-01BackGrammar.QXD 6/19/02 12:32 PM Page 389 Plural of Nouns Singular Plural no change or add das Zimmer die Zimmer umlaut die Mutter die Mütter die Ecke die Ecken add -n, -en or -nen der Herr die Herren die Freundin die Freundinnen der Tag die Tage add -e or -¨e die Stadt die Städte das Buch die Bücher add -¨er das Fach die Fächer das Auto die Autos add -s das Büro die Büros Inverted Word Order 1. -

Sandwiches & Rounds

Sandwiches" & Rounds For more information and samples call 781-598-4451 PSR-700FB Sandwich Round PFI-720 5” Sandwich Round 65/3 oz. FB 50/4.5 oz. PB PSR-700 4” Sandwich Round A little bigger than our ever popular 65/3 oz. PB 4” round, this larger hamburger adds A Traditional French round. great taste to an upscale burger or The crisp, golden crust provides sandwich. Light crust on the outside distinctive texture for burgers and and great taste on the inside. upscale sandwich creations. LRS-790 Brioche Roll-Sliced STP-262 Sourdough Tuscan 72/2.75 oz. FB 60/5 oz. PB PBP-704LS Brioche Rolls Great for grilling and creating upscale 72/2.75 oz. FB sandwiches, the Sourdough Tuscan A sweet dough made with butter has a great natural sour flavor due and eggs creates a roll that results to its long fermentation process. in a wow factor for any sandwich. SFR-200 French 8” Sandwich HWL-230 Honey Wheat Grain Loaf 60/4 oz. PB 70/3.75 oz. FB A great tasting French sandwich roll is This Honey Wheat Grain loaf is so a crowd favorite for deli sandwiches or good; it’s gotten Fan Mail! The ideal table bread. Its light crusty outside and bread for two or three, serve it warm moist inside, makes it one of our most with butter on a rustic breadboard or requested items! in a basket. Deep, rich brown, textured with a grain-filled crust, and light moist interior that releases a tempting aroma when you break it open. -

Hot Fresh Bread Handcrafted Every Day!

Hot Fresh Bread Handcrafted Every Day! We start baking at 3:45am and hot bread comes out of the oven from 9am to noon! Get it Hot! MAY Breads Everyday Honey Whole Wheat, Honey White, Cinnamon Burst, Cinnamon Monkey, Alaskan Sourdough and Sourdough Baguette. Monday 9 Grain, Apple Cinnamon Swirl, Italian Herb Parmesan Sourdough and Jalapeno Cheddar Sourdough. Tuesday High Five Fiber, Bakers Choice, Blueberry Swirl, Sun-Dried Tomato Herb Sourdough and Tomato Pesto Provolone Sourdough. Wednesday Whole Grain Goodness, Apple Cinnamon Swirl, Italian Herb Sourdough and Roasted Garlic Rosemary Sourdough. Thursday High Five Fiber, Potato Cheddar Chive, Blueberry Swirl, 3 Cheese Sourdough and Kalamata Olive Parmesan Sourdough. Friday Dakota, Popeye, Apple Cinnamon Swirl, Sun-Dried Tomato Herb Sourdough, Bacon Cheddar Sourdough and French Bread Saturday High Five Fiber, Apple Cinnamon Swirl, Cheese & Garlic Swirl, Tomato Pesto Provolone, Jalapeno Cheddar Sourdough, Italian Herb Sourdough and French Bread Fresh Made Sandwiches May Goodies Premium Great Harvest bread Everyday combined with select fresh ingredients make a delicious and Blueberry Cream Scones, Cinnamon Cream Scones, Cinnamon Rolls, Breakfast Rolls wholesome sandwich. Come in and and Bread Pudding. let us make one fresh for you! Monday Salted Caramel Cookies, Apple Streusel Coffeecake, Honey Bran Muffin. Turkey & Swiss Tuesday California Cobb Oatmeal Chocolate Chip Cookies, Lemon Blueberry Muffin and Pound Cake, Banana Bread and Muffins Pepper Bleu Roast Beef Wednesday Harvest Veggie Dillon Cookies, M&M Cookies, Almond Poppyseeed Muffin and Tea Cake, Honey Wine Country Bran Muffin. Chipotle Turkey Thursday Salted Caramel Cookies, Zucchini Bread, Granny's Crumb Cake and Muffins. Turkey Pesto Panini Friday Bacon Chicken Club Panini Oatmeal Chocolate Chip Cookies, Snickdoodles, Pumpkin Chocolate Chip Bread and Tuscan Chicken Panini Carrot Cake. -

Homemade Sandwich Bread

Homemade Sandwich Bread photo by Helena Gifford Ingredients 3 cups all-purpose flour ½ cup milk ½ to ⅔ cup hot water 4 tablespoons of melted butter or vegetable oil 2 tablespoons granulated sugar 1 ¼ teaspoons salt 1 packet active dry yeast dissolved in 1 tablespoon warm (95-115°F) water or 2 teaspoons instant yeast Recipe Homemade Sandwich Bread In a large bowl, combine all of the ingredients and stir until the dough stops sticking to the sides of the bowl. Transfer the dough to a lightly greased surface, oil your hands, and knead the dough for six to eight minutes or until it becomes smooth and supple. People have different ways of kneading, but I repeatedly fold the dough in half and turn it 90 degrees before the next fold. You should be stretching the dough, not tearing it. By kneading the dough, you are forming gluten and making it nice and elastic. You’ll know when the dough is done if it quickly returns to its original shape when you stretch it out a little bit. Or you can just knead it until your arms get tired. Transfer the dough to a lightly greased bowl, cover the bowl with a lightly greased plastic wrap, and allow the dough to rise until puffy but not necessarily doubled in size. It should take about one to two hours, depending on the warmth of your kitchen. If your kitchen is cold (less than 70°F), you can let the dough rise in an oven with the light on instead. Gently deflate the dough and transfer it to a lightly oiled surface. -

Global Bread Survey 2018

Global Bread Survey 2018 - White Bread, Wholemeal Bread, Flat Bread, Mixed Grain Bread Notes: Data per 100g and per portion was collected online and in store between July and December 2017. See WASH website for further information. Portion size as stated on pack Data sorted from highest to lowest for salt per 100g Colour coding according to DH Front of Pack Guidance: Green ≤0.3/100g, Amber >0.3 - ≤1.5g, Red >1.5g /100g, >1.8g/portion for salt NA = Data not available GF = Gluten Free Portion Size Sodium/100g Salt/portion Sodium/portion Country Product Name Brand/Manufacturer Bread Type Salt / 100g (g) (g) (mg) (g) (mg) Argentina Jumbo artesanal pan de molde multicereal con chia Jumbo Mixed Grain Bread 50.0 NA NA NA NA Argentina Pan multicereal sin sal agregada Natural bread Mixed Grain Bread 50.0 NA NA NA NA Belgium pain multigrains Beck Mixed Grain Bread NA NA NA NA NA Belgium pain multi-céréales Damhert Mixed Grain Bread NA NA NA NA NA Belgium Meerzaden brood Genius (Albert Heijn) Mixed Grain Bread 29.0 NA NA NA NA Belgium pain blanc pur froment Beck White Bread NA NA NA NA NA Belgium pain blanc GLUTEN FREE Damhert White Bread, GF NA NA NA NA NA Belgium pain gris pur froment Beck Wholemeal Bread NA NA NA NA NA Belgium pain tournesol Kelderman Wholemeal Bread NA NA NA NA NA Bulgaria Bread type "Tipov" for toast SaviMeks Wholemeal Bread 34.0 NA NA NA NA Bulgaria Bread whole grain for toast SaviMeks Wholemeal Bread 34.0 NA NA NA NA Canada Ancient Grain Bread - Loaf Loblaws Mixed Grain Bread NA NA NA NA NA Canada Bocata Ronda - 10 Pack Boulangerie -

Winter 2019-2020

Frozen Autumn Winter 2019-2020 Frozen Autumn Winter thomasridley.co.uk 2019 - Delivering the best in foodservice... 2020 Welcome to our new brochure... delivering the best in Foodservice... Frozen2019/2020 t Thomas Ridley, we know how e pride ourselves on delivering elebrating over 100 years as a Limited importantA it is to keep up with the latest qualityW products, value, convenience Company,C we continuously invest in our trends and demands of this ever changing and exceptional customer service, whilst people and our business to ensure Thomas industry by responding quickly to ensure retaining the personal touch. As one of Ridley Foodservice is at the forefront of the we are offering everything that you need the largest independent wholesalers, wholesale food industry. Our team have for your menus. With this in mind, we we can adapt quickly to market changes incomparable experience in their fields of present to you our full Frozen guide with and lead the way in working with our expertise and are passionate in working new, innovative products from both local customers and suppliers to ensure together to achieve further success into the and national brands as well as our own mutually beneficial relationships. future. Customer service remains at the heart Country Range brand. This enables us to of our business ensuring you have peace of provide a total food service solution to mind and the confidence that we will go that the whole of the catering industry. extra mile to make sure you get the products you require, when you need them. ur easy to use, industry leading website is the best way to find enhanced product information including clear allergen labelling, nutritionalO advice and storage instructions. -

Cooking Until Cheese Is Melted and Lightly Browned

Delicious Sandwich Recipes Delicious Sandwich Recipes Collection of Delicious Sandwich Recipes Ebook with Master Resale and Redistribution Rights!! Legal Notice:- You have full rights to sell or distribute this document. You can edit or modify this text without written permission from the compiler. This Ebook is for informational purposes only. While every attempt has been made to verify the information provided in this recipe Ebook, neither the author nor the distributor assume any responsibility for errors or omissions. Any slights of people or organizations are unintentional and the Development of this Ebook is bona fide. This Ebook has been distributed with the understanding that we are not engaged in rendering technical, legal, accounting or other professional advice. We do not give any kind of guarantee about the accuracy of information provided. In no event will the author and/or marketer be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential or other loss or damage arising out of the use of this document by any person, regardless of whether or not informed of the possibility of damages in advance. Contents - 1 - Delicious Sandwich Recipes Contents ABC Sandwich ALL-AMERICAN BARBECUE SANDWICHES All American Club Sandwich Acapulco Fishburgers Anytime Apple Muffinwiches Alaska Salmon Sandwich Stuffer Alaska Salmon Salad Sandwich Alan's Special Sandwich Apple-Mustard Sliced Ham Antipasto Sandwich Asian Turkey Burgers Avocado and Chicken Tortas Avocado Bacon Sandwiches Avocado Chicken Melt Avocado Chicken Salad Sandwich -

Sandwich Bread + Grades 9-10 - Common Core English Language Arts - Language Analysis

Families: Pilot Light Family Meal Lessons are designed to easily bring food education into your home. We recommend using the Family Resources in the following way: 1. Watch the Family Meal video for the lesson as a family. 2. Make the recipe as a family. 3. In the Common Core Connections section, children can learn through and about food while strengthening Common Core English Language Arts or Math skills. 4. Family Discussion questions and Extension Activities are provided to allow learners of all ages opportunities to participate in the learning experience! Pilot Light Family Meal Lesson Sandwich Bread + Grades 9-10 - Common Core English Language Arts - Language Analysis Suggested Recipe Age Range: 4 and up with adult help Recipe by Chef Justin Large: Sandwich Bread Ingredients: ● 6.5 to 7.5 cups unbleached, all purpose flour ● 2.5 tsp kosher salt ● 1.5 Tbsp instant yeast ● 1/4 cup honey (or sugar) ● 2.75 cups 90-95F water ● 1/4 cup vegetable oil ● Softened butter for greasing pans Materials: ● Large mixing bowls ● Large metal spoon or rubber spatula ● Whisk ● Plastic wrap or large kitchen towel ● Large knife ● Two 8.5x4.5(9x5)inch bread pans ● Wire cooling rack ● Cutting Board ©2020 Pilot Light. All Rights Reserved. Directions: 1. Using the softened butter, grease the bread pans. 2. In a large mixing bowl, combine 3 cups of the AP flour, and all of the yeast. Using the whisk, mix until combined. 3. Add the water, oil, and honey to the flour mix. Using the metal spoon or spatula, mix until combined.