Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Beginning of the Church

Excerpts from the “The Historical Road of Eastern Orthodoxy” By Alexander Schmemann Translated by Lynda W. Kesich (Please get the full version of this book at your bookstore) Content: 1. The Beginning of the Church. Acts of the Apostles. Community in Jerusalem — The First Church. Early Church Organization. Life of Christians. Break with Judaism. The Apostle Paul. The Church and the Greco-Roman World. People of the Early Church. Basis of Persecution by Rome. Blood of Martyrs. Struggle of Christianity to Keep its Own Meaning. The New Testament. Sin and Repentance in the Church. Beginnings of Theology. The Last Great Persecutions. 2. The Triumph Of Christianity. Conversion of Constantine. Relations between Church and State. The Arian Disturbance. Council of Nicaea — First Ecumenical Council. After Constantine. The Roman Position. Countermeasures in the East. End of Arianism. New Relation of Christianity to the World. The Visible Church. Rise of Monasticism. State Religion — Second Ecumenical Council. St. John Chrysostom. 3. The Age Of The Ecumenical Councils. Development of Church Regional Structure. The Byzantine Idea of Church and State Constantinople vs. Alexandria The Christological Controversy — Nestorius and Cyril. Third Ecumenical Council. The Monophysite Heresy. Council of Chalcedon (Fourth Ecumenical Council). Reaction to Chalcedon — the Road to Division. Last Dream of Rome. Justinian and the Church. Two Communities. Symphony. Reconciliation with Rome — Break with the East. Recurrence of Origenism. Fifth Ecumenical Council. Underlying Gains. Breakup of the Empire — Rise of Islam. Decay of the Universal Church Last Efforts: Monothelitism. Sixth Ecumenical Council. Changing Church Structure. Byzantine Theology. Quality of Life in the New Age. Development of the Liturgy. -

Working Papers on Suffering and Hope

FAITH AND WITNESS COMMISSION CANADIAN COUNCIL OF CHURCHES WORKING PAPERS ON SUFFERING AND HOPE Editor: Dr Paul Ladouceur PREFACE 2 SUFFERING, SACRIFICE AND SURVIVAL AS A FRAMEWORK FOR THINKING ABOUT MORAL AGENCY by Dr Gail Allan (United Church of Canada) 3 BIBLE STUDY ON SUFFERING AND HOPE by Neil Bergman (Christian Church – Disciples of Christ) 14 PAIN AND SUFFERING IN THE ORTHODOX PERSPECTIVE by Fr. Dr. Jaroslaw Buciora (Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Canada) 17 “FROM FEAR TO TRUST”: A THEOLOGICAL DISCOURSE ON THEODICY by Fr. Dr. Jaroslaw Buciora (Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Canada) 26 REFLECTION ON ROMANS 8:16-28, 31-39 by Rev. Fred Demaray (Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec) 36 CROSS WORDS WITH GOSPEL REFLECTIONS - A RESPONSIVE READING ON THE SEVEN WORDS FROM THE CROSS by Rev. Fred Demaray (Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec) 38 GOD DOES NOT WANT SUFFERING - A PATRISTIC APPROACH TO SUFFERING by Dr Paul Ladouceur (Orthodox Church in America) 41 REFLECTION ON THE BOOK OF JOB: JOB, THE GREAT SUFFERER OF THE OLD TESTAMENT Dr Paul Ladouceur (Orthodox Church in America) 46 SUFFERING ACCORDING TO JOHN PAUL II by Dr Christophe Potworowski (Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops) 49 SUFFERING AND HOPE: ANGLICAN PERSPECTIVES by Rev. Dr. Ian Ritchie (Anglican Church of Canada) 54 TEACHING ON SUFFERING AND HOPE IN THE SALVATION ARMY by Major Kester Trim (The Salvation Army) 61 SUFFERING AND HOPE: A LUTHERAN PERSPECTIVE by Rev. Beth Wagschal (Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada) 66 THE DOOR OF HOPE by Fr. Lev Gillet (“A Monk of the Eastern Church”) 68 February 2010. -

15/35/54 Liberal Arts and Sciences Russian & East European Center

15/35/54 Liberal Arts and Sciences Russian & East European Center Paul B. Anderson Papers, 1909-1988 Papers of Paul B. Anderson (1894-1985), including correspondence, maps, notes, reports, photographs, publications and speeches about the YMCA World Service (1919-58), International Committee (1949-78), Russian Service (1917-81), Paris Headquarters (1922-67) and Press (1919-80); American Council of Voluntary Agencies (1941-47); Anglican-Orthodox Documents & Joint Doctrinal Commission (1927-77); China (1913-80); East European Fund & Chekhov Publishing House (1951-79); displaced persons (1940-52); ecumenical movement (1925-82); National Council of Churches (1949-75); prisoners of war (1941-46); Religion in Communist Dominated Areas (1931-81); religion in Russia (1917-82); Russian Correspondence School (1922-41); Russian emigrés (1922-82); Russian Orthodox Church (1916-81) and seminaries (1925-79); Russian Student Christian Movement (1920-77); Tolstoy Foundation (1941-76) and War Prisoners Aid (1916-21). For an autobiographical account, see Donald E. Davis, ed., No East or West: The Memoirs of Paul B. Anderson (Paris: YMCA-Press, 1985). For Paul Anderson's "Reflections on Religion in Russia, 1917-1967" and a bibliography, see Richard H. Marshall Jr., Thomas E. Bird and Andrew Q. Blane, Eds., Aspects of Religion in the Soviet Union 1917-1967 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1971). Provenance Note: The Paul B. Anderson Papers first arrived at the University Archives on May 16, 1983. They were opened on September 11, 1984 and a finding aid completed on December 15, 1984. The cost of shipping the papers and the reproduction of the finding aid was borne by the Russian and East European Center. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Ludmila & Paul Kulikovsky №117 December 2017 Detail on a door in the Russian Orthodox Church of Saint Elizabeth in Wiesbaden, Germany The conference and exhibition "Hessian Princesses in Russian History" in Frankfurt On December 19, in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, the scientific and educational conference "Hessian Princesses in Russian History" arranged by the Russian Ministry of culture and the Elizabeth-Sergei Enlightenment Society, was opened. The conference was held in the "Knights hall" of the "German order" - commonly known as the "Teutonic Knights" - the full name being "The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem". It is a Catholic religious order founded as a military order c. 1190 in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. More than 50 Russian and German historians, archivists, and cultural figures attended the conference. Among them were: Alla Manilova, Deputy Minister of Culture of the Russian Federation; Anna Gromova, Chairman of the Elizabeth-Sergei Enlightenment Society"; Karl Weber, Director of the Office of State Palaces and Parks of the Land of Hesse; Sergey Mironenko, Scientific director of the State Archives of the Russian Federation; Elena Kalnitskaya, General director of Museum "Peterhof", and Ludmila and Paul Kulikovsky. The relations between the Hessen and Russian Imperial houses started in the reign of Empress Catherine the Great. In 1773 she invited the Hessian Princess, Wilhelmina Louisa of Hesse-Darmstadt, to St. Petersburg. On 29 September the same year Princess Wilhelmina married Empress Catherine the Great's son, the Tsarevich Paul Petrovich - the later Emperor Paul I. In Russia she was named Grand Duchess Natalia Alexeevna. -

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches A

Atlas cover:Layout 1 4/19/11 11:08 PM Page 1 Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches Assembling a mass of recently generated data, the Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches provides an authoritative overview of a most important but often neglected segment of the American Christian community. Protestant and Catholic Christians especially will value editor Alexei Krindatchʼs survey of both Eastern Orthodoxy as a whole and its multiple denominational expressions. J. Gordon Melton Distinguished Professor of American Religious History Baylor University, Waco, Texas Why are pictures worth a thousand words? Because they engage multiple senses and ways of knowing that stretch and deepen our understanding. Good pictures also tell compelling stories. Good maps are good pictures, and this makes the Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Churches, with its alternation and synthesis of picture and story, a persuasive way of presenting a rich historical journey of Orthodox Christianity on American soil. The telling is persuasive for both scholars and adherents. It is also provocative and suggestive for the American public as we continue to struggle with two issues, in particular, that have been at the center of the Orthodox experience in the United States: how to create and maintain unity across vast terrains of cultural and ethnic difference; and how to negotiate American culture as a religious other without losing oneʼs soul. David Roozen, Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research Hartford Seminary Orthodox Christianity in America has been both visible and invisible for more than 200 years. Visible to its neighbors, but usually not well understood; invisible, especially among demographers, sociologists, and students of American religious life. -

Aspects of Church History Aspects of Church History

ASPECTS OF CHURCH HISTORY ASPECTS OF CHURCH HISTORY VOLUME FOUR in the Collected "Works of GEORGES FLOROVSKY Emeritus Professor of Eastern Church History Harvard University NORDLAND PUBLISHING COMPANY BELMONT, MASSACHUSETTS 02178 MAJOR WORKS BY GEORGES FLOROVSKY The Eastern Fathers of the Fourth Century (in Russian) The Byzantine Fathers from the Fifth to the Eighth Century (in Russian) The Ways of Russian Theology (in Russian) Bible, Church, Tradition: An Eastern Orthodox View (Vol. I in The Collected Works) Christianity and Culture (Vol. II in The Collected Works) Creation and Redemption (Vol. Ill in The Collected Works) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 74-22862 ISBN 0-913124-10-9 J) Copyright 1975 by NORD LAND PUBLISHING COMPANY All Rights Reserved PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA About the Author Born in Odessa in 1893, Father Georges Florovsky was Assistant Professor at the University of Odessa in 1919. Having left Russia, Fr. Florovsky taught philosophy in Prague from 1922 until 1926. He was then invited to the chair of Patrology at St. Sergius' Orthodox Theological Institute in Paris. In 1948 Fr. Florovsky came to the United States. He was Professor and Dean of St. Vladimir's Theological School until 1955, while also teaching as Adjunct Profes- sor at Columbia University and Union Theological Seminary. From 1956 until 1964 Fr. Florovsky held the chair of Eastern Church History at Harvard University. Since 1964 he has taught Slavic studies and history at Princeton Uni- versity. Fr. Georges Florovsky, Emeritus Professor of Eastern Church History at Harvard University and recipient of numerous honorary degrees, is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1981, No.51

www.ukrweekly.com СВОБОДАХЗУОВООА Ж УКРАЇНСЬКИЙ ЩОЛ,ІННИК ^Ч0рР иЛЯАІНІІЬПАІІ^ І ажгч Ukrainian Weekly і w– PUBLISHED BY THE UKRAINIAN NATIONAL ASSOCIATION INC., A FRATERNAL, NON-PROFIT ASSOCIATION : voi. LXXXVIII No. 51 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, DECEMBER 20, i98i 25 cents ХРИСТОС РОЖДАЄТЬСЯ - CHRIST IS BORN .r"– Jacques Hnizdovsky's depiction of the traditional Ukrainian Christmas Eve dinner. Patriarch,hierarchs issue Christmas message Soviets sentence four for ROME - in their Christmas ing that Jesus Christ came primarily pastoral letter released here, Patriarch not to the chosen few of society, not posting Solidarity Day leaflets Josyf and the hierarchs of the "Po– to the powerful, but to the down- misna" Ukrainian Catholic Church trodden, the persecuted, the for– NEW YORK - Four persons were " Mr. Naboka - of writing and urged Ukrainians throughout the gotten. "For each person, the Nati– sentenced by the municipal court disseminating "slanderous" poetry and world to come to the aid of the vity of Christ brings a special bless– in Kiev, Ukraine, to three years each in articles; persecuted Church and their suffer– ing: for sinners it brings salvation; for Soviet prison camps for posting leaflets ' Ms. Lokhvytska and Ms. Cher– ing brothers and sisters in Ukraine. the suffering it brings hope; for the urging their countrymen to mark the niavska - co-authoring an article titled The pastoral also focused on the dying it brings eternal life," the Day of Solidarity with Ukrainian "Charter"; importance of a Christian outlook on hierarchs wrote. Political Prisoners which falls on Ja– " Ms. Lokhvytska — writing articles life and stressed that this outlook is The pastoral letter went on to note nuary 12 each year. -

MONASTIC ECONOMY ACROSS TIME Wealth Management, Patterns, and Trends

CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDY MONASTIC ECONOMY SOFIA ACROSS TIME WEALTH MANAGEMENT, PATTERNS, AND TRENDS The Centre for Advanced Study So a (CAS) Roumen Avramov The book aims at a readership of both econo- EDITED BY is an independent non-pro t institution Aleksandar Fotić mists and historians. Beyond the well-known ROUMEN AVRAMOV with strong international and Elias Kolovos Weberian thesis concerning the role of Protes- ALEKSANDAR FOTIĆ multidisciplinary pro le set up Phokion P. Kotzageorgis tantism in the development of capitalism, mo- ELIAS KOLOVOS for the promotion of freedom Dimitrios Kalpakis nastic economies are studied to assess their PHOKION P. KOTZAGEORGIS of research, scholarly excellence Styliani N. Lepida impact on the religious patterns of economic be- and academic cooperation Preston Perluss havior. Those issues are discussed in the frame in the Humanities Gheorghe Lazăr of key economic concepts such as rationality, and Social Sciences. Konstantinos Giakoumis state intervention, networking, agency, and gov- Wealth Management, Patterns, and Trends Patterns, Management, Wealth Lidia Cotovanu ernance. The book includes essays concerning Andreas Bouroutis Byzantine, Ottoman and modern South-Eastern www.cas.bg Brian Heffernan Europe, and early modern and modern Western Antoine Roullet Europe. Survival and continuity of the monastic Michalis N. Michael wealth is considered as an example of success- Daniela Kalkandjieva ful handling of real estate transactions, ows of Isabelle Depret funds, and contacts with nancial institutions. Isabelle Jonveaux Moreover, the book focuses on the economic im- pact of the privileged relations of monasticism with the secular powers. Finally, the question is raised how the monastic economy (still) matters in the contemporary world. -

Renewing the Jesus Movement in the Episcopal Church: Weaving Good News Into Spiritual Formation Robert Swope [email protected]

Masthead Logo Digital Commons @ George Fox University Doctor of Ministry Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2019 Renewing the Jesus Movement in the Episcopal Church: Weaving Good News Into Spiritual Formation Robert Swope [email protected] This research is a product of the Doctor of Ministry (DMin) program at George Fox University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Swope, Robert, "Renewing the Jesus Movement in the Episcopal Church: Weaving Good News Into Spiritual Formation" (2019). Doctor of Ministry. 301. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dmin/301 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE FOX UNIVERSITY RENEWING THE JESUS MOVEMENT IN THE EPISCOPAL CHURCH: WEAVING GOOD NEWS INTO SPIRITUAL FORMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF PORTLAND SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY ROBERT SWOPE PORTLAND, OREGON FEBRUARY 2019 Portland Seminary George Fox University Portland, Oregon CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ________________________________ DMin Dissertation ________________________________ This is to certify that the DMin Dissertation of Robert Swope has been approved by the Dissertation Committee on February 14, 2019 for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in Leadership and Spiritual Formation Dissertation Committee: Primary Advisor: David Robinson, DMin Secondary Advisor: Mary Pandiani, DMin Lead Mentor: MaryKate Morse, PhD Copyright © 2019 by Robert Swope All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To my beloved Anam Cara, Sharon, whose tender wisdom, compassion, and brilliance have encouraged and transformed me during our life together and beyond. -

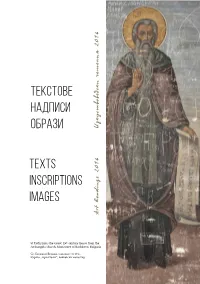

Текстове Надписи Образи Texts Inscriptions Images

ТЕКСТОВЕ НАДПИСИ ОБРАЗИ Изкуствоведски четения 2016 TEXTS INSCRIPTIONS IMAGES Art Readings 2016 St Euthymius the Great, 19th century fresco from the Archangels church, Monastery of Bachkovo, Bulgaria Св. Евтимий Велики, стенопис от 19 в., църква „Архангели“, Бачковски манастир ИЗКУСТВОВЕДСКИ ЧЕТЕНИЯ Тематично годишно рецензирано издание за изкуствознание в два тома ART READINGS Thematic annual peer-reviewed edition in Art Studies in two volumes Международна редакционна колегия International Advisory Board Andrea Babuin (Italy) Konstantinos Giakoumis (Albania) Nenad Makulijevic (Serbia) Vincent Debiais (France) Редактори от ИИИзк In-house Editorial Board Ivanka Gergova Emmanuel Moutafov Научни редактори на тома Scholarly Edited by Emmanuel Moutafov Jelena Erdeljan (Serbia) Institute of Art Studies 21 Krakra Str. 1504 Sofia Bulgaria www.artstudies.bg © Институт за изследване на изкуствата, БАН, 2017 ИЗКУСТВОВЕДСКИ ЧЕТЕНИЯ Тематично годишно рецензирано издание за изкуствознание в два тома 2016/ т. I – Старо изкуство ТЕКСТОВЕ • НАДПИСИ • ОБРАЗИ TEXTS • INSCRIPTIONS •IMAGES ART READINGS Thematic annual peеr-reviewed edition in Art Studies in two volumes 2016/ vol. I – Old Art Под научната редакция на Емануел Мутафов Йелена Ерделян Scholarly edited by Emmanuel Moutafov Jelena Erdeljan София 2017 Книгата се издава със съдействието на Плесио компютърс Content Art Readings 2016 ............................................................................................................11 Emmanuel Moutafov The Visual Language of Roman Art and Roman -

The Personalism of Denis De Rougemont

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! The personalism of Denis de Rougemont: ! Spirituality and politics in 1930s Europe! ! ! ! ! ! Emmanuelle Hériard Dubreuil! ! St John’s College, 2005! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This dissertation is submitted for the degree of! Doctor of Philosophy! !1 ! ! !2 Abstract! ! ! ! ! ! Neither communist, nor fascist, the personalist third way was an original attempt to remedy the malaise of liberal democracies in 1930s Europe. Personalism puts the emphasis on the human person – understood to be an individual in relation to others – as the foundation and aim of society. Yet, because of the impossibility of subjecting the human person to a systematic definition, personalism remains complex and multifaceted, to the extent that it might be best to speak of ‘personalisms’ in the plural. The various personalist movements that emerged in France in the 1930s are little known, and the current historiography in English misrepresents them. ! This dissertation is a study of the various personalist movements based in France in the 1930s, examining their spiritual research and political philosophy through the vantage point of Swiss writer Denis de Rougemont (1906-1985). In Rougemont lies the key to understanding the personalist groupings because he was the only thinker to remain active in the two foremost movements (Ordre Nouveau and Esprit) throughout the 1930s. The personalism of Ordre Nouveau was the most original, in both senses of the term. It deserves particular attention as an important political philosophy and an attempt to justify political and economic federalism in 1930s Europe. Whilst an Ordre Nouveau activist, Rougemont can be looked upon as the mediator and federator of personalisms in the 1930s. ! However, Rougemont’s particular contribution to personalist thought was more spiritual and theological than political or economic. -

Theological Studies

Theological Studies http://tsj.sagepub.com/ Orthodox Ecumenism and Theology: 1978−83 Michael A. Fahey Theological Studies 1983 44: 625 DOI: 10.1177/004056398304400405 The online version of this article can be found at: http://tsj.sagepub.com/content/44/4/625.citation Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Theological Studies, Inc Additional services and information for Theological Studies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://tsj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://tsj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Dec 1, 1983 What is This? Downloaded from tsj.sagepub.com by guest on March 9, 2014 Theological Studies 44 (1983) CURRENT THEOLOGY ORTHODOX ECUMENISM AND THEOLOGY: 1978-83 MICHAEL A. FAHEY, S.J. Concordia University, Montreal The period covered in this survey of Orthodox theology, 1978 to the eve of the General Assembly meeting of the World Council of Churches in Vancouver 1983, has been a time rich in symbolic events and solid theological achievements for Orthodoxy.1 A high-ranking Metropolitan, Nikodim of Leningrad, died in the arms of Pope John Paul I during a formal visit in a year that came to be known as the year of three popes. For the first time in history an Orthodox bishop preached at a liturgical service in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. The official international theo logical commission between the Orthodox Church and the Roman Cath olic Church met on the islands of Patmos and Rhodes and later in Munich, where for the first time since the Council of Florence a joint theological statement was agreed to.