MONASTIC ECONOMY ACROSS TIME Wealth Management, Patterns, and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emmanuele F.M. Emanuele Emmanuele Francesco Maria

Emmanuele F.M. Emanuele Emmanuele Francesco Maria Emanuele, descendant of one of the most illustrious ancient noble Christian Catholic families of medieval Spain (1199) and Southern Italy, Baron. University Professor, Supreme Court lawyer, economist, expert in financial, tax and insurance issues, essayist and author of books on economics and poetry. EDUCATION - Primary school: “S. Anna”, Palermo; - Lower secondary school: “Istituto Gonzaga” (Jesuit), Palermo; - Upper secondary school: “Istituto Don Bosco - Ranchibile” (Salesian), Palermo; - Lyceum: “Giuseppe Garibaldi”, Palermo; - Degree in law awarded by the University of Palermo in 1960; - Business training course held by ISDA (Istituto Superiore per la Direzione Aziendale), 1962-63; - Financial and Monetary Economics course at the Harvard Summer School, Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts U.S.A., through a scholarship granted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1968. PROFESSORSHIPS Former - Assistant to the Chair of Economic Policy at the Faculty of Statistical, Demographic and Actuarial Sciences of the ‘La Sapienza’ University of Rome, 1963-74; - Tenured assistant to the Chair of Taxation Law at the Faculty of Political Science of the University of Naples; - Professor of Tax Law at the University of Salerno, 1971-81; - Professor of Tax and Public Sector Law at the LUISS Guido Carli University, 1982-83; - Professor of Tax Law at the LUISS Guido Carli University, 1983-84 and 1993-96; - Professor of Financial Law at the LUISS Guido Carli University, 1984-92; - Professor -

Maxi-Catalogue 2014 Maxi-Catalogue 2014

maxi-catalogue 2014 maxi-catalogue 2014 New publications coming from Alexander Press: 1. Διερχόμενοι διά τού Ναού [Passing Through the Nave], by Dimitris Mavropoulos. 2. Εορτολογικά Παλινωδούμενα by Christos Yannaras. 3. SYNAXIS, The Second Anthology, 2002–2014. 4. Living Orthodoxy, 2nd edition, by Paul Ladouceur. 5. Rencontre avec λ’οrthodoxie, 2e édition, par Paul Ladouceur. 2 Alexander Press Philip Owen Arnould Sherrard CELEBR ATING . (23 September 1922 – 30 May 1995 Philip Sherrard Philip Sherrard was born in Oxford, educated at Cambridge and London, and taught at the universities of both Oxford and London, but made Greece his permanent home. A pioneer of modern Greek studies and translator, with Edmund Keeley, of Greece’s major modern poets, he wrote many books on Greek, Orthodox, philosophical and literary themes. With the Greek East G. E. H. Palmer and Bishop Kallistos Ware, he was and the also translator and editor of The Philokalia, the revered Latin West compilation of Orthodox spiritual texts from the 4th to a study in the christian tradition 15th centuries. by Philip Sherrard A profound, committed and imaginative thinker, his The division of Christendom into the Greek East theological and metaphysical writings covered issues and the Latin West has its origins far back in history but its from the division of Christendom into the Greek East consequences still affect western civilization. Sherrard seeks and Latin West, to the sacredness of man and nature and to indicate both the fundamental character and some of the the restoration of a sacred cosmology which he saw as consequences of this division. He points especially to the the only way to escape from the spiritual and ecological underlying metaphysical bases of Greek Christian thought, and contrasts them with those of the Latin West; he argues dereliction of the modern world. -

Greece I.H.T

Greece I.H.T. Heliports: 2 (1999 est.) GREECE Visa: Greece is a signatory of the 1995 Schengen Agreement Duty Free: goods permitted: 800 cigarettes or 50 cigars or 100 cigarillos or 250g of tobacco, 1 litre of alcoholic beverage over 22% or 2 litres of wine and liquers, 50g of perfume and 250ml of eau de toilet. Health: a yellow ever vaccination certificate is required from all travellers over 6 months of age coming from infected areas. HOTELS●MOTELS●INNS ACHARAVI KERKYRA BEIS BEACH HOTEL 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63913 (0663) 63991 CENTURY RESORT 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63401-4 (0663) 63405 GELINA VILLAGE 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 64000-7 (0663) 63893 [email protected] IONIAN PRINCESS CLUB-HOTEL 491 00 Acharavi Kerkyra ACHARAVI KERKYRA GREECE TEL: (0663) 63110 (0663) 63111 ADAMAS MILOS CHRONIS HOTEL BUNGALOWS 848 00 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22226, 23123 (0287) 22900 POPI'S HOTEL 848 01 Adamas, on the beach Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22286-7, 22397 (0287) 22396 SANTA MARIA VILLAGE 848 01 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE TEL: (0287) 22015 (0287) 22880 Country Dialling Code (Tel/Fax): ++30 VAMVOUNIS APARTMENTS 848 01 Adamas Milos ADAMAS MILOS GREECE Greek National Tourism Organisation: Odos Amerikis 2b, 105 64 Athens Tel: TEL: (0287) 23195 (0287) 23398 (1)-322-3111 Fax: (1)-322-2841 E-mail: [email protected] Website: AEGIALI www.araianet.gr LAKKI PENSION 840 08 Aegiali, on the beach Amorgos AEGIALI AMORGOS Capital: Athens Time GMT + 2 GREECE TEL: (0285) 73244 (0285) 73244 Background: Greece achieved its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1829. -

Saint Patrick Parish ‘A Faith Community Since 1870‘ 1 Cross Street Whitinsville, MA 01588

Saint Patrick Parish ‘A Faith Community since 1870‘ 1 Cross Street Whitinsville, MA 01588 MASS SCHEDULE Office Hours: Monday-Friday 9:00 AM - 4:00 PM Saturday: 4:30 PM Sunday 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM, 5:00 PM Rectory Phone: 508-234-5656 Monday– Wednesday 8:30 AM Rectory Fax: 508-234-6845 Religious Ed. Phone: 508-234-3511 Sacrament of Reconciliation: Parish Website: www.mystpatricks.com Confessions are offered every Saturday from 3:30 - 4:00 PM in the Church or by calling the Find us on Facebook at Parish Office for an appointment. St Patricks Parish Whitinsville St. Patrick Church, Whitinsville MA October 16, 2016 Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time Rev. Tomasz Borkowski: Deacon Patrick Stewart: Deacon Chris Finan: Deacon Pastor Deacon [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Christina Pichette: Mrs. Shelly Mombourquette: Pastoral Associate to Youth Ministry Administrative Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Maryanne Swartz: Mrs. Mary Contino: Wedding Coordinator Coordinator of Children’s Ministries [email protected] [email protected] Mrs. Jackie Trottier: Operations Manager Mr. Jack Jackson: Cemetery Superintendent: [email protected] [email protected] Ms. Jeanne LeBlanc: Ministry Scheduler Mrs. Marylin Arrigan: Staff Support, Bulletin [email protected] [email protected] RELIGIOUS EDUCATION SCHEDULE OUR LADY OF THE VALLEY REGIONAL SCHOOL Pre school Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM 71 Mendon Street, Uxbridge, MA 01569 Kindergarten Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM 508-278-5851 First Grade Sunday 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM www.ourladyofthevalleyregional.com Grades 2 & 3 Sunday 11:20 AM - 12:20 PM Grades 4 & 5 Sunday 8:50 AM - 9:50 AM Free Breakfast every Saturday from 8-10 Children are to attend the 10:00 am Mass and take part AM for those in need. -

CBM Short Catalogue : NT Corpus Explanation: Codex Type T

CBM Short Catalogue : NT corpus Explanation: codex type T Sources 1Catalogues : of MSS per library Table I: Tetraevangelion codex type (T 0001 - 1323) Sources 4 : Catalogues of NT Mss CODEX TYPE CODE PLACE LIBRARY - HOLDING LIBRARY CODE AGE - date SCRIPT IRHT INTF: GA A T 0001 Alexandria Greek Orthodox Patriarchal Library Ms. 77 (276) 1360 AD Mn ● 904 T 0002 Alexandria Greek Orthodox Patriarchal Library Ms. 451 (119) 1381 AD Mn ● 903 St. Petersburg Russian National Library Ms. gr. 398 T 0003 (etc.) Amorgos Panagias Chozoviotissas Monastery Ms. 7 XIII Mn ● 2647 T code Amorgos Panagias Chozoviotissas Monastery Ms. 12 XIII Mn ● 1306 T code Amorgos Panagias Chozoviotissas Monastery Ms. 27 XIII Mn ● 1308 T code Amorgos Panagias Chozoviotissas Monastery Ms. 38 XIV Mn ● 1307 T code Andros Panachrantou Monastery Ms. 11 XV Mn ● 1383 T code Andros Panachrantou Monastery Ms. 43 XVI Mn ● 2630 T code Andros Zoodochou Peges (Hagias) Monastery Ms. 53 1539 AD? Mn ● 1362 T code Andros Zoodochou Peges (Hagias) Monastery Ms. 56 XIV Mn ● 1363 T code Ankara National Library of Turkey Ms. gr. 1 (548) XIV Mn ● 2439 T code Ankara National Library of Turkey Ms. gr. 2 (470) XII Mn ● 1803 T code Ankara National Library of Turkey Ms. gr. 5 (470A) XII Mn ● 1804 T code Ankara National Library of Turkey Ms. gr. 49 (7) 1668 Mn ● 1802 T code Ankara Turkish Historical Society Ms. 5 XII Mn ● 650 T code Ann Arbor, MI University of Michigan, Special Collections Library Ms. 15 XII Mn ● 543 T code Ann Arbor, MI University of Michigan, Special Collections Library Ms. -

Michael Panaretos in Context

DOI 10.1515/bz-2019-0007 BZ 2019; 112(3): 899–934 Scott Kennedy Michael Panaretos in context A historiographical study of the chronicle On the emperors of Trebizond Abstract: It has often been said it would be impossible to write the history of the empire of Trebizond (1204–1461) without the terse and often frustratingly la- conic chronicle of the Grand Komnenoi by the protonotarios of Alexios III (1349–1390), Michael Panaretos. While recent scholarship has infinitely en- hanced our knowledge of the world in which Panaretos lived, it has been approx- imately seventy years since a scholar dedicated a historiographical study to the text. This study examines the world that Panaretos wanted posterity to see, ex- amining how his post as imperial secretary and his use of sources shaped his representation of reality, whether that reality was Trebizond’s experience of for- eigners, the reign of Alexios III, or a narrative that showed the superiority of Tre- bizond on the international stage. Finally by scrutinizing Panaretos in this way, this paper also illuminates how modern historians of Trebizond have been led astray by the chronicler, unaware of Panaretos selected material for inclusion for the narratives of his chronicle. Adresse: Dr. Scott Kennedy, Bilkent University, Main Camous, G Building, 24/g, 06800 Bilkent–Ankara, Turkey; [email protected] Established just before the fall of Constantinople in 1204, the empire of Trebi- zond (1204–1461) emerged as a successor state to the Byzantine empire, ulti- mately outlasting its other Byzantine rivals until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1461. -

Jesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration

JesuitsJesuits and Eucharistic Concelebration James J. Conn, S.J.S.J. Jesuits,Jesuits, the Ministerial PPriesthood,riesthood, anandd EucharisticEucharistic CConcelebrationoncelebration JohnJohn F. Baldovin,Baldovin, S.J.S.J. 51/151/1 SPRING 2019 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits is a publication of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States. The Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality is composed of Jesuits appointed from their provinces. The seminar identifies and studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially US and Canadian Jesuits, and gath- ers current scholarly studies pertaining to the history and ministries of Jesuits throughout the world. It then disseminates the results through this journal. The opinions expressed in Studies are those of the individual authors. The subjects treated in Studies may be of interest also to Jesuits of other regions and to other religious, clergy, and laity. All who find this journal helpful are welcome to access previous issues at: [email protected]/jesuits. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Note: Parentheses designate year of entry as a seminar member. Casey C. Beaumier, SJ, is director of the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. (2016) Brian B. Frain, SJ, is Assistant Professor of Education and Director of the St. Thomas More Center for the Study of Catholic Thought and Culture at Rock- hurst University in Kansas City, Missouri. (2018) Barton T. Geger, SJ, is chair of the seminar and editor of Studies; he is a research scholar at the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies and assistant professor of the practice at the School of Theology and Ministry at Boston College. -

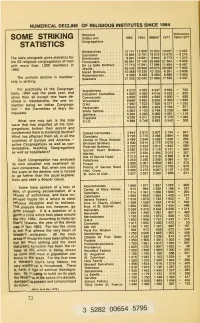

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

The Roots of the Fondazione Roma: the Historical Archives

The Historical Archives are housed in the head-offices of the Fondazione Roma, situated in the THE ROOTS OF THE FONDAZIONE ROMA: THE HISTORICAL prestigious Palazzo Sciarra which was built in the second half of the sixteenth century by the ARCHIVES Sciarra branch of the Colonna family who held the Principality of Carbognano. Due to the beauty of the portal, the Palace was included amongst the ‘Four Wonders of Rome’ together with the In 2010, following a long bureaucratic procedure marked by the perseverance of the then Borghese cembalo, the Farnese cube and the Caetani-Ruspoli staircase. During the eighteenth Chairman, now Honorary President, Professor Emmanuele F.M. Emanuele, Fondazione Roma century, Cardinal Prospero Colonna renovated the Palace with the involvement of the famous acquired from Unicredit a considerable amount of records that had been accumulated over five architect Luigi Vanvitelli. The Cardinal’s Library, the small Gallery and the Mirrors Study, richly hundred years, between the sixteenth and the twentieth century, by two Roman credit institutions: decorated with paintings, are some of the rooms which were created during the refurbishment. the Sacro Monte della Pietà (Mount of Piety) and the savings bank Cassa di Risparmio. The documents are kept inside a mechanical and electric mobile shelving system placed in a depot The Honorary President Professor Emanuele declares that “The Historical Archives are a precious equipped with devices which ensure safety, the stability and constant reading of the environmental source both for historians and those interested in the vicissitudes of money and credit systems and indicators and respect of the standards of protection and conservation. -

1 the Beginning of the Church

Excerpts from the “The Historical Road of Eastern Orthodoxy” By Alexander Schmemann Translated by Lynda W. Kesich (Please get the full version of this book at your bookstore) Content: 1. The Beginning of the Church. Acts of the Apostles. Community in Jerusalem — The First Church. Early Church Organization. Life of Christians. Break with Judaism. The Apostle Paul. The Church and the Greco-Roman World. People of the Early Church. Basis of Persecution by Rome. Blood of Martyrs. Struggle of Christianity to Keep its Own Meaning. The New Testament. Sin and Repentance in the Church. Beginnings of Theology. The Last Great Persecutions. 2. The Triumph Of Christianity. Conversion of Constantine. Relations between Church and State. The Arian Disturbance. Council of Nicaea — First Ecumenical Council. After Constantine. The Roman Position. Countermeasures in the East. End of Arianism. New Relation of Christianity to the World. The Visible Church. Rise of Monasticism. State Religion — Second Ecumenical Council. St. John Chrysostom. 3. The Age Of The Ecumenical Councils. Development of Church Regional Structure. The Byzantine Idea of Church and State Constantinople vs. Alexandria The Christological Controversy — Nestorius and Cyril. Third Ecumenical Council. The Monophysite Heresy. Council of Chalcedon (Fourth Ecumenical Council). Reaction to Chalcedon — the Road to Division. Last Dream of Rome. Justinian and the Church. Two Communities. Symphony. Reconciliation with Rome — Break with the East. Recurrence of Origenism. Fifth Ecumenical Council. Underlying Gains. Breakup of the Empire — Rise of Islam. Decay of the Universal Church Last Efforts: Monothelitism. Sixth Ecumenical Council. Changing Church Structure. Byzantine Theology. Quality of Life in the New Age. Development of the Liturgy. -

IN DARKEST ENGLAND and the WAY out by GENERAL WILLIAM BOOTH

IN DARKEST ENGLAND and THE WAY OUT by GENERAL WILLIAM BOOTH (this text comes from the 1890 1st ed. pub. The Salvation Army) 2001 armybarmy.com To the memory of the companion, counsellor, and comrade of nearly 40 years. The sharer of my every ambition for the welfare of mankind, my loving, faithful, and devoted wife this book is dedicated. This e-book was optically scanned. Some minor updates have been made to correct some spelling errors in the original book and layout in-compatibilities 2001 armybarmy.com PREFACE The progress of The Salvation Army in its work amongst the poor and lost of many lands has compelled me to face the problems which an more or less hopefully considered in the following pages. The grim necessities of a huge Campaign carried on for many years against the evils which lie at the root of all the miseries of modern life, attacked in a thousand and one forms by a thousand and one lieutenants, have led me step by step to contemplate as a possible solution of at least some of those problems the Scheme of social Selection and Salvation which I have here set forth. When but a mere child the degradation and helpless misery of the poor Stockingers of my native town, wandering gaunt and hunger-stricken through the streets droning out their melancholy ditties, crowding the Union or toiling like galley slaves on relief works for a bare subsistence kindled in my heart yearnings to help the poor which have continued to this day and which have had a powerful influence on my whole life. -

British Reports on Ottoman Syria in 1821-1823

University of North Florida UNF Digital Commons History Faculty Publications Department of History 2-16-2019 Rebellion, Unrest, Calamity: British Reports on Ottoman Syria in 1821-1823 Theophilus C. Prousis University of North Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ahis_facpub Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Prousis, Theophilus C., "Rebellion, Unrest, Calamity: British Reports on Ottoman Syria in 1821-1823" (2019). History Faculty Publications. 29. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ahis_facpub/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2-16-2019 All Rights Reserved Chronos- Revue d’Histoire de l’Université de Balamand, is a bi-annual Journal published in three languages (Arabic, English and French). It deals particularly with the History of the ethnic and religious groups of the Arab world. Journal Name: Chronos ISSN: 1608-7526 Title: Rebellion, Unrest, Calamity: British Reports on Ottoman Syria in 1821-1823 Author(s): Theophilus C Prousis To cite this document: Prousis, T. (2019). Rebellion, Unrest, Calamity: British Reports on Ottoman Syria in 1821-1823. Chronos, 29, 185-210. https://doi.org/10.31377/chr.v29i0.357 Permanent link to this document: DOI: https://doi.org/10.31377/chr.v29i0.357 Chronos uses the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA that lets you remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes.