RESPECT the Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Inimitable? The Afterlives and Cultural Memory of Charles Dickens’s Characters England, Maureen Bridget Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 08. Oct. 2021 1 INIMITABLE? THE AFTERLIVES AND CULTURAL MEMORY OF CHARLES DICKENS’S CHARACTERS Maureen Bridget England King’s College London Candidate Number: 1233164 Thesis for PhD in English Literature 2 This paper is dedicated to the two doctors in my life who inspired me to pursue this dream: Martin England and Jenna Higgins 3 ‘Any successfully evoked character, no matter how apparently insignificant, stands a good chance of surviving its creator.’ David Galef, The Supporting Cast (1993) 4 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................ -

Deedie Pearson

Deedie Pearson Transcript of an Oral History Conducted by Anjuli Grantham at Kodiak, Alaska On June 12, 18, and 26, 2015 (With subsequent corrections and additions) Kodiak Historical Society About West Side Stories This oral history is part of the West Side Stories project of the Kodiak Historical Society. West Side Stories is a public humanities and art project that intended to document the history of the west side of Kodiak Island through oral history, photography, and art. The oral histories chart the personal stories of individuals with a longtime connection to the west side of Kodiak Island, defined for the scope of this project as the area buffeted by the Shelikof Strait that stretches from Kupreanof Strait south to the village of Karluk. The project endeavored to create historical primary source material for a region that lacks substantive documentation and engage west side individuals in the creation of that material. The original audio recording of this interview is available by contacting the Kodiak Historical Society. Additional associated content is available at the Kodiak Historical Society/ Baranov Museum, including photographs of interview subjects and west side places taken during the summer of 2015, archival collections related to the west side, and journals and art projects created by west side residents in 2015. This project is made possible due to the contributions of project partners and sponsors, including the Alaska Historical Society, Alaska Humanities Forum, Alaska State Council on the Arts, Kodiak Maritime Museum, Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, Kodiak Public Broadcasting, Prince William Sound Regional Citizens Advisory Council, and Salmon Project. -

Glisan, Rodney L. Collection

Glisan, Rodney L. Collection Object ID VM1993.001.003 Scope & Content Series 3: The Outing Committee of the Multnomah Athletic Club sponsored hiking and climbing trips for its members. Rodney Glisan participated as a leader on some of these events. As many as 30 people participated on these hikes. They usually travelled by train to the vicinity of the trailhead, and then took motor coaches or private cars for the remainder of the way. Of the four hikes that are recorded Mount Saint Helens was the first climb undertaken by the Club. On the Beacon Rock hike Lower Hardy Falls on the nearby Hamilton Mountain trail were rechristened Rodney Falls in honor of the "mountaineer" Rodney Glisan. Trips included Mount Saint Helens Climb, July 4 and 5, 1915; Table Mountain Hike, November 14, 1915; Mount Adams Climb, July 1, 1916; and Beacon Rock Hike, November 4, 1917. Date 1915; 1916; 1917 People Allen, Art Blakney, Clem E. English, Nelson Evans, Bill Glisan, Rodney L. Griffin, Margaret Grilley, A.M. Jones, Frank I. Jones, Tom Klepper, Milton Reed Lee, John A. McNeil, Fred Hutchison Newell, Ben W. Ormandy, Jim Sammons, Edward C. Smedley, Georgian E. Stadter, Fred W. Thatcher, Guy Treichel, Chester Wolbers, Harry L. Subjects Adams, Mount (Wash.) Bird Creek Meadows Castle Rock (Wash.) Climbs--Mazamas--Saint Helens, Mount Eyrie Hell Roaring Canyon Mount Saint Helens--Photographs Multnomah Amatuer Athletic Association Spirit Lake (Wash.) Table Mountain--Columbia River Gorge (Wash.) Trout Lake (Wash.) Creator Glisan, Rodney L. Container List 07 05 Mt. St. Helens Climb, July 4-5,1915 News clipping. -

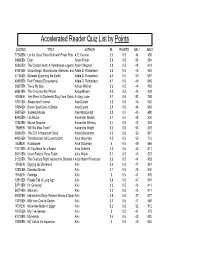

Accelerated Reader Quiz List by Points

Accelerated Reader Quiz List by Points QUIZNO TITLE AUTHOR BL POINTS ABL1 ABL2 77268EN Let the Good Times Roll with Pirate Pete aA.E. Cannon 2.6 0.5 44 453 36996EN Deer Aaron Frisch 5.8 0.5 54 894 25862EN The Crystal Heart: A Vietnamese Legend Aaron Shepard 3.8 0.5 48 618 61081EN Groundhogs: Woodchucks, Marmots, and Adele D. Richardson 3.2 0.5 46 535 51184EN Minerals (Exploring the Earth) Adele D. Richardson 4.3 0.5 50 687 43998EN Rain Forests (Ecosystems) Adele D. Richardson 4.1 0.5 49 660 28837EN Twice My Size Adrian Mitchell 2.6 0.5 44 453 68561EN The Crow and the Pitcher Aesop/Brown 2.5 0.5 44 439 6300EN Yeh-Shen: A Cinderella Story from China Ai-Ling Louie 5.1 0.5 52 798 77074EN Always and Forever Alan Durant 3.2 0.5 46 535 78584EN Brown Bear Gets in Shape Alan Durant 2.6 0.5 44 453 56876EN Scaredy Mouse Alan MacDonald 2.8 0.5 45 480 80400EN Lila Bloom Alexander Stadler 3.7 0.5 48 604 17540EN Mouse Surprise Alexandra Whitney 2.4 0.5 43 425 7598EN Will We Miss Them? Alexandra Wright 5.3 0.5 53 825 20660EN The Gift: A Hanukkah Story Aliana Brodmann 4.3 0.5 50 687 44054EN The Mountain that Loved a Bird Alice McLerran 4.5 0.5 50 715 5539EN Roxaboxen Alice McLerran 4 0.5 49 646 77073EN All You Need for a Beach Alice Schertle 2.3 0.5 43 411 30316EN Uncle Farley's False Teeth Alice Walsh 3.1 0.5 46 522 21232EN The Glorious Flight: Across the Channel wAlice/Martin Provensen 2.6 0.5 44 453 9763EN Digging Up Dinosaurs Aliki 3.6 0.5 47 591 13804EN Dinosaur Bones Aliki 3.7 0.5 48 604 9765EN Feelings Aliki 2 0.5 41 370 13815EN Fossils Tell of -

Astatula Elementary School 2007 Accelerated Reader List – by Title

Astatula Elementary School 2007 Accelerated Reader List – By Title Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 64468EN 100 Monsters in My School Bonnie Bader 2.4 0.5 73204EN The 100th Day of School (Holiday Brenda Haugen 2.7 0.5 1224EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 2.6 0.5 14796EN The 13th Floor: A Ghost Story Sid Fleischman 4.4 4.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 101417EN The 19th Amendment Michael Burgan 6.4 1.0 15903EN 19th Century Girls and Women Bobbie Kalman 5.5 0.5 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 3.8 1.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4.0 8001EN 50 Below Zero Robert N. Munsch 2.4 0.5 76205EN 97 Ways to Train a Dragon Kate McMullan 3.3 2.0 11001EN "A" Is for Africa Ifeoma Onyefulu 4.5 0.5 83128EN Aaaarrgghh! Spider! Lydia Monks 0.8 0.5 103423EN Aargh, It's an Alien! Karen Wallace 3.0 0.5 1551EN Aaron Copland Mike Venezia 5.5 0.5 14601EN Abby Wolfram Hanel 3.7 0.5 19378EN Abby and the Mystery Baby Ann M. Martin 4.6 4.0 19385EN Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Ann M. Martin 4.5 4.0 70144EN ABC Dogs Kathy Darling 4.1 0.5 61510EN Abe Lincoln and the Muddy Pig Stephen Krensky 3.7 0.5 45400EN Abe Lincoln Remembers Ann Turner 4.1 0.5 1093EN Abe Lincoln's Hat Martha Brenner 2.6 0.5 61248EN Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved B Kay Winters 3.6 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3.0 76357EN The Abernathy Boys L.J. -

The Complete Costume Dictionary

The Complete Costume Dictionary Elizabeth J. Lewandowski The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2011 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth J. Lewandowski Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations created by Elizabeth and Dan Lewandowski. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., 1960– The complete costume dictionary / Elizabeth J. Lewandowski ; illustrations by Dan Lewandowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dress—Dictionaries. I. Title. GT507.L49 2011 391.003—dc22 2010051944 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Dan. Without him, I would be a lesser person. It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause and diligence without reward. -

Fancy Dresses Described;

:5^ 1 : Fancy dresses described; OR, WHAT TO WEAR AT FANCY BALLS. By ARDERN holt. FIFTH EDITION. LONDON DEBENHAM & FREEBODY, WIGMORE STREET AND WELBECK STREET ; WYMAN & SONS, 74-76, GREAT QUEEN STREET AND ALL BOOKSELLERS. ENTERED AT STATIONERS HALL. '^/f"] 1 hit DEBENHAM & FREEBODY Invite an inspection of their Novelties and Specialties in COURT DRESSES AND TRAINS, PRESENTATION DRESSES, BALL, EVENING, AND VISITING DRESSES, COSTUMES, TAILOR-MADE JACKETS AND GOWNS, TEA-GOWNS, DRESSING-GOWNS, MANTLES, MILLINERY, AND WEDDING TROUSSEAUX. s:p'ecia;i. o.'Esre'NS in NA TIONAL, ilf/Srp^^GJlL. '^ANDjFAJk'f V COSTUMES jF<:^i?J fli'Bi^&Aj}^xya''tiEkigijzAi.s, and * FANcYBALLS. DEBENHAM & FREEBODY, WIGMORE STREET c^' WELBECK STREET, LONDON, W. aiFT OF PREFACE HE Fourth Edition of Ardern Holt's "Fancy Dresses Described" being exhausted, we have made arrange- ments for the publication of the Fifth Edition with such corrections as experience dictates, and a very large addition to the number of characters detailed. The suggestions we have received have been carefully noted, and the result is a larger and more comprehensive work than any hitherto published. The inquiry for Coloured Plates has induced us to select sixteen favourite Models for Illustration in Colours, of a completely new character, as well as a new series of smaller Illustrations, and we trust they will add greatly to the usefulness of the book. The Author's name is a guarantee for the correctness of the descriptions and accuracy of details; and we have endea- voured (as in former editions) to maintain such simplicity as will enable many ladies to produce the costumes at home. -

Imports, Mechanisation and the Decline of the English Plaiting Industry: the View from the Hatters' Gazette, Luton 1873-1900

Imports, Mechanisation and the Decline of the English Plaiting Industry: the View from the Hatters’ Gazette, Luton 1873-1900 Catherine Robinson Submitted to the University of Hertfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MA by Research June 2016 Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been possible without the kindness, encouragement, help and support of Sarah Lloyd and Julie Moore from the History Department at the University of Hertfordshire. I would like to thank Veronica Main who was the Significant Collections Curator during my research time at Luton’s Wardown Park Museum, for all her help and support; it was Veronica’s suggestion to research the decline of the plaiting industry. Veronica shared her passion for the straw hat and plait industries with me, welcomed me into the museum, facilitated my research of the Hatters’ Gazette, showed me the collections and shared her immense expertise. Being at Wardown Park Museum and reading the 19th century Hatters’ Gazette and being able to see and study the hats and plaits themselves, was a truly remarkable experience and one that I shall always treasure. I would also like to thank the staff at Wardown Park Museum for making my time researching not only fascinating but also so enjoyable. I would like to thank Elise Naish, Museums Collections Manager, for allowing me to research the Hatters’ Gazette at the museum during a very busy time for staff. I would like to thank Mary Miah for all her help – from getting the volumes of the Hatters’ Gazette out ready for my research, to scanning old documents and photographing images to be used in this research, to sharing her work space – thank you Mary. -

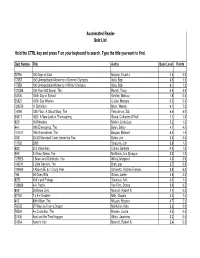

KNAPP AR LIST for Web Site

Accelerated Reader Quiz List Hold the CTRL key and press F on your keyboard to search. Type the title you want to find. Quiz Number Title Author Book Level Points 75796 100 Days of Cool Murphy, Stuart J. 2.6 0.5 17357 100 Unforgettable Moments in Summer Olympics Italia, Bob 6.5 1.0 17358 100 Unforgettable Moments in Winter Olympics Italia, Bob 6.1 1.0 122356 100-Year-Old Secret, The Barrett, Tracy 4.4 4.0 74705 100th Day of School Schiller, Melissa 1.8 0.5 35821 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery 3.0 0.5 128370 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4.1 7.0 14796 13th Floor: A Ghost Story, The Fleischman, Sid 4.4 4.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace, Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda Lee 5.2 1.0 661 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 101417 19th Amendment, The Burgan, Michael 6.4 1.0 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 11592 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 3.3 1.0 125923 3 Bears and Goldilocks, The Willey, Margaret 4.3 0.5 140211 3 Little Dassies, The Brett, Jan 3.7 0.5 109460 4 Kids in 5E & 1 Crazy Year Schwartz, Virginia Frances 3.8 6.0 166 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. -

Family Fun in Store at the SNPJ Recreation Center PROSVETA Crossword Puzzle

Your for News prosvetaOfficial Publication of the Slovene National Benefit Society In This Issue YEAR CXIV USPS: 448-080 MONDAY, MARCH 1, 2021 ISSUE 3 ISSN: 1080-0263 Slovenia from the Source .......................... 3 SNPJ Fraternal Sympathies ...................4-5 Family fun in store at the SNPJ Recreation Center PROSVETA Crossword Puzzle ................. 5 by josepH C. evanisH out at the cabins and enjoy the friendship members is $140 per person; for non-members briefly SNPJ National President/CEO of fellow SNPJ members. Of course, there’s the fee is $200 per person. There is also an ad- BOROUGH OF SNPJ, Pa. — We’re looking always time for the pool in addition to other ditional lodging fee based on the type of cabin forward to the summer season at the SNPJ special activities, many times featuring live in which you will be staying. For a two-bedroom Required Lodge report Recreation Center and counting the days until entertainment! Upper Cabin (numbers 3-24), the fee is $350 for deadlines moved to June Family Week 2021, scheduled Sunday, Aug. Campers will enjoy three meals a day. the week. For a two-bedroom Lower Cabin, the 1, through Saturday, Aug. 7. Although the meal service will conclude with fee is $230 for the week. For a one-bedroom IMPERIAL, Pa. — Due to the cur- For those of you who aren’t aware of every- breakfast on Friday, Aug. 6, you’ll be able to Lower Cabin, the fee is $120 for the week. rent state of the pandemic affecting the thing that goes on at Family Week, think of it stay in your cabin and enjoy all of the Friday Want to stay in the newly-renovated Cabins 1 country, all Lodge reporting requirements as a summer camp for families. -

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Monday, December 1, 2014 8:13:30 AM School: Plymouth Christian Elementary School

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Monday, December 1, 2014 8:13:30 AM School: Plymouth Christian Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 57450 EN 100 Days of School Harris, Trudy LG 2.3 0.5 262 NF 61130 EN 100 School Days Rockwell, Anne LG 2.8 0.5 667 F ÷ 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf LG 1.4 0.5 189 F 35821 EN 100th Day Worries Cuyler, Margery LG 3.0 0.5 956 F 12059 EN 14 Forest Mice and the Harvest Iwamura, Kazuo LG 2.9 0.5 449 F Moon Watch, The 12060 EN 14 Forest Mice and the Spring Iwamura, Kazuo LG 3.2 0.5 475 F Meadow Picnic, The 12061 EN 14 Forest Mice and the Summer Iwamura, Kazuo LG 2.9 0.5 473 F Laundry Day, The 12062 EN 14 Forest Mice and the Winter Iwamura, Kazuo LG 3.1 0.5 465 F Sledding Day, The 11101 EN 16th Century Mosque, A Macdonald, Fiona MG 7.7 1.0 5,118 NF 15902 EN 19th Century Clothing Kalman, Bobbie MG 6.0 1.0 3,211 NF 30561 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Vogel, Malvina G. MG 5.2 3.0 16,876 F 122178 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Verne, Jules MG 4.6 1.0 7,193 F (Saddleback) 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Verne, Jules MG 10.0 28.0 138,138 F (Unabridged) 160234 EN 20 Fun Facts About the Niver, Heather Moore LG 5.9 0.5 1,755 NF Declaration of Independence 160235 EN 20 Fun Facts About the Levy, Janey LG 5.5 0.5 1,701 NF Presidency 160236 EN 20 Fun Facts About the U.S. -

Masquerade and Carnival: Their Customs and Costumes

1 Purchased by the Mary Stuart Book Fund Founded A.D. 1893 Cooper Union Library ]y[ASQUERADE AND (^ARNIVAL Their Custofns and Costumes. PRICE : FIFTY CENTS or TWO SHILLINGS. UE!"V"IS:H!3D j&.]Sri> EJISTL A-UG-IEIZD. PUBLISHED BY The Butterick Publishing Co. (Limited), London, and New York, 1892. — — 'Fair ladies mask'd, are roses in their bud.'' Shakespeare. 'To brisk notes in cadence beating. filance their many twinkling feet.'' Gray. "When yon do dance, I wish you A wave of the sea, that you might ever do Nothing but that." — Winter's Tale. APR 2. 1951 312213 INTR0DUeTI0N, all the collection of books and pamphlets heretofore issued upon the IN subject of Masquerades and kindred festivities, no single work has contained the condensed and general information sought by the multi- tude of inquirers who desire to render honor to Terpsichore in her fantastic moods, in the most approved manner and garb. Continuous queries from our correspondents and patrons indicated this lack, and research confirmed it. A work giving engravings and descriptions of popular costumes and naming appropriate occasions for their adoption, and also recapitulating the different varieties of Masquerade entertainments and their customs and requirements was evidently desired and needed; and to that demand we have responded in a manner that cannot fail to meet with approval and appreciation. In preparing this book every available resource has been within our reach, and the best authorities upon the subject have been consulted. These facts entitle us to the full confidence of our patrons who have only to glance over these pages to decide for themselves that the work is ample and complete, and that everyone may herein find a suitable costume for any festivity or entertainment requiring Fancy Dress, and reliable decisions as to the different codes of etiquette governing such revelries.