Patient-Evaluated Cognitive Function Measured with Smartphones And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning Languages Through Walking Tours with Native Speakers

LEARNING LANGUAGES THROUGH WALKING TOURS WITH NATIVE SPEAKERS www.neweuropetours.eu SANDEMANs NEW Europe is the world’s largest city walking tour provider. With hundreds of thousands of five-star reviews, millions of satisfied guests annually and outstanding service, for a lot of travelers, SANDEMANs tours are an important part of their trip. While many customers choose SANDEMANs to get to know a city with the help of an informed, entertaining and unforgettable expert guide, there is a growing segment of guests who use SANDEMANs to learn a language. With over 600 independent guide partners, native speakers of English and Spanish as well as native speakers of the respective national language are available in all 20 cities in which SANDEMANs is active. With trained English, Spanish and German teachers and a fascinating selection of stories, SANDEMAN tours are an entertaining and interesting way to learn a language. Why SANDEMANs NEW Europe?The SANDEMANs SANDEMANsStory NEW Europe at a glance Qualified language teachers In our multilingual office team Freelance guides from 25 countries Over 600 Freelance guide partners At SANDEMANs NEW Europe, we work with tour guides who specialise in making history, society and culture come alive. These young (and young at heart) guides are experts not only in the cities they call home, but in keeping guests of all ages, nationalities and backgrounds engaged - this is particularly true for school groups. 235,000 Five-star reviews These guides are native English/Spanish and German-speakers from all over the world, giving students the opportunity to hear a range of real-life accents and vocabulary, and to interact with people from different cultures. -

Pia Lindgren

Pia Lindgren Fra: TMFKP Sekretariat Emne: Svar. Politikerspørgsmål om vejarbejde på Østerbrogade - tidsplan til Østerbro Handelsforening og/eller de enkelte butiksejere. eDoc sag 2021-0052863 Fra: TMFKP MKB Rådhuspost Sendt: 25. februar 2021 12:53 Til: Flemming Steen Munch (Borgerrepræsentationen) Cc: Stine Grangaard Emne: Svar. Politikerspørgsmål om vejarbejde på Østerbrogade ‐ tidsplan til Østerbro Handelsforening og/eller de enkelte butiksejere. eDoc sag 2021‐0052863 Kære Flemming Steen Munch Tak for din henvendelse til forvaltningen af 16. februar 2021 vedrørende kommunikation med erhvervsdrivende i forbindelse med vejarbejde på Østerbrogade fra marts 2021-sommeren 2022. Jeg besvarer din henvendelse, da den vedrører mit ansvarsområde i forvaltningen. Fra begyndelsen af marts 2021 og frem til forsommeren 2022 vil der være vejarbejde på Østerbrogade. I vedhæftede tidsplan fremgår det, i hvilke perioder, der arbejdes på henholdsvis østsiden og vestsiden af delstrækningerne Blegdamsgade – Jagtvej og Classensgade – Blegdamsvej. Fra juli 2021 til ultimo oktober 2021 foregår der også vejarbejder i Viborggade, på strækningen mellem Østerbrogade og Randersgade. Udførelsestidsplanen for Viborggade fremgår ligeledes af den vedlagte tidsplan. Det ses, at arbejder foregår i den periode, hvor der spilles EM i fodbold, og hvor der ikke foregår arbejder i Østerbrogade. Forvaltningen har orienteret Østerbro Lokaludvalg og Østerbro Handelsforening om tidsplanen og vil fremadrettet være i en løbende dialog med de enkelte erhvervsdrivende om forholdene foran deres butikker, cafeer, mv. Dialogen vil finde sted både før og under arbejdernes udførelse, således der kan skabes de bedste betingelser for den enkelte erhvervsdrivende. Det skal i den forbindelse bemærkes, at der under arbejdernes gennemførelse altid vil være adgang til alle gadedøre og butikker via gangbroer eller plader. -

Om Østerbro Cykelkort København Kommunes Cykeldogmer

A B C D E F G H J #5 GERSONSVEJ 9 VANDTÅRNSVEJ GLADSAXEVEJ STRANDVEJEN 2 GLADSAXE SØBORG HOVEDGADE GLADSAXE MØLLEVEJ IDRÆTSPARKIDRÆTSPARK HILLERØDMOTORVEJEN GLADSAXE RINGVEJ LYNGBYVEJ Hør klokken RYVANGS ALLÉ IRÆTSANLÆGIRÆTSANLÆG DYSSEGÅRDSVEJ IRÆTSANLÆG Hellerup LYNGBYVEJ Station HELSINGØRMOTORVEJEN RINGVEJ GLADSAXEVEJ HERLEV RYVANGS ALLÉ DYSSEGÅRDS PARKEN BERNSTORFFSVEJ TUBORGVEJ MOTORRING 3 TUBORGVEJ TUBORGVEJ STRANDVEJEN OM ØSTERBRO CYKELKORT KØBENHAVN KOMMUNES RYMARKSVEJ 1 GYNGEMOSEN ØSTERBRO CYKELKORT ER EN OVERSIGT OVER EKSISTERENDE OG KOMMENDE CYKELSTIER PÅ FREDERIKS TUBORGVEJ BORGVEJ PHILLIP HEYMANS ALLÉ ØSTERBRO. DE KOMMENDE CYKELSTIER ER EN DEL AF CYKELPAKKE ØSTERBRO, HVIS FORMÅL ER 9 7 AT FORBEDRE CYKELFORBINDELSERNE PÅ ØSTERBRO, BÅDE GENERELT OG I FORBINDELSE MED CYKELDOGMER RYVANGS ALLÉ 9 EMDRUPVEJ HØJE GLADSAXEVEJ HELSINGØRMOTORVEJEN LYNGBYVEJ ANLÆGGET AF NORDHAVNSVEJ. 2 LYNGBYVEJ MØRKHØJVEJ #2 STRANDØRE HILLERØDMOTORVEJEN #1 4 TUBORGVEJ Emdrup ØSTERBRO LOKALUDVALG HAR SAMARBEJDET MED TEKNIK- OG MILJØFORVALTNINGEN OM DE Hold til højre Station STRANDPROMENADEN Spred god karma STRANDVEJEN KONKRETE FORSLAG I CYKELPAKKEN, MED UDGANGSPUNKT I DE EKSISTERENDE PLANER FOR FREDERIKSBORGVEJ NYE CYKELRUTER. HERLEV HOVEDGADE PILEGÅRDENS RYVANGS ALLÉ LERSØ PARKALLÉ ØSTERBRO HAVEBY LYNGBYVEJ 2 LYNGBYVEJ STRANDVÆNGET UDOVER AT KORTET KAN GIVE DIG VIDEN OMNOVEMBERVEJ DE KOMMENDE CYKELPLANER PÅ ØSTERBRO, KAN Svanemøllen 9 Station FREDERIKSSUNDSVEJ TAGENSVEJ DU OGSÅ BRUGE KORTET SOM INSPIRATION, NÅR DU SKAL BEVÆGE DIG RUNDT I BYDELEN PÅ Ryparken -

Nørrebro Tour a Livable & Sustainable Neighborhood?

Nørrebro Tour A livable & Sustainable Neighborhood?ROVSINGSGADE VERMUNDSGADE ALDERSROGADE g)Nørrebropark/ ROVSINGSGADE h)BanannaPark Superkilen HARALDSGADE This local neighborhood park has since its opening in 2009 found international NørrebroPark: Walk through this park. TAGENSVEJ interest. This park has become perticularly well recieved by local users. We nd a Notice the greenery, aesthetics and visual MJØLNERPARKEN very high amount of daily users. The three surrounding institutions (day-care, identity. Does this park correspond with grade school and after school activity center) use the park as their extended the demoraphics of the people using it? SKJOLDS schoolyard/gym/playground. Note the functions/programs of the park. Notice Which elements of the park stand out to PLADS the interaction/overlapping of the programs and thus also the user goups. Does you? Why? overlap of programs promote social interaction across user goups? Does diver- Superkilen: Continue across Hillerødgade sity of activity promote user goup diversity? Notice the visual identity of the and Nørrebrogade. You will get to a red HEIMDALSGADE park. Notice the surrounding windows, the park has 24-7 ’natural surveillance’ HERMODSGADE thermo-plast square; this is Red Square. JAGTVEJ (Jane RÅDMANDSGADEJacobs term). Note if the kids are accompanied by parents or on their Notice the urban furniture and the BORGMESTERVANGEN own? Does it feel safe? Does it feel livable? Can you tell this use to be a gang design of the square. Notice the peole and dealer hot spot? Would you consider this gentried or livable? HAMLETSGADE using it; is there social interaction bet- ween people? Continue further on to LYNGSIES Black Square. -

Velkommen Til Danmarks Dejligste Domicil Må Vi Byde På En Rundvisning? Frydenlund 30

VELKOMMEN TIL DANMARKS DEJLIGSTE DOMICIL MÅ VI BYDE PÅ EN RUNDVISNING? FRYDENLUND 30 Frydenlund 30 i Vedbæk er ikke et nybyggeri, men det er en nyistandsæt- telse og nytænkning. Rammerne ude er grønne og næsten overvældende. Rammerne inde er brede og gavmilde. Der er banet vej for både lyset, prak- tikken og det funktionelle. Her tilbyder vi Danmarks måske smukkeste domicil skræddersyet til jeres behov. Bistro, kaffebar, lounge og receptionsservices kan tilkøbes, og I får adgang til konference- og mødefaciliteter på Frydenlund 30, men også i Bredgade 30 i København. GÅ PÅ OPDAGELSE HER DOMICIL MED SKOV, SØ OG PARK På Frydenlund 30 i Vedbæk danner spektakulær natur rammen om denne unikke ejendom. Her er ro til fordybelse og innovation. Både sø, skov og park er tilknyttet domicilet, i perfekt kombination med moderne faciliteter og gode trafikale forhold. BYGNING J (KANTINE) ST. 1.2221.148 m m²² KLD. 280649 m m²² BYGNING G VARMECENTRAL BYGNING E 1.SAL 357 m² (TEK) BYGNING K,L, M, N ST. 1.814m² 1.SAL1. SAL 2.7282.597 m² m² ST. 2.7702.747 m² m² PARTERRE 762722 m² m² KLD. 569633 m² m² BYGNING B 1.SAL 704625 mm²² ST. 705649 m m²² BYGNING H 1.SAL 1.053 m² ST. 1.110 m² KLD. 494 m² BYGNING D ST. 485 m² BYGNING C ST. 359 m² KLD. 357 m² BYGNING A 1.SAL 646 m² BYGNING R + S ST. 698 m² ST. R R 172139 m m²² ST. S S 172139 m m²² EKSISTERENDE FORHOLD BRUTTOAREALER EN OASE INDE. EN OASE UDE NYE RAMMER MED NYE MULIGHEDER På Frydenlund 30 får I 6.829 m² kontor fordelt på 4 ejendomme, som er forbundet. -

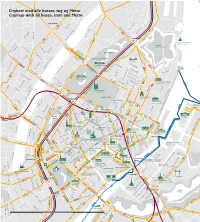

Byens Net Til

Citykort med alle busser, tog og Metro Citymap with all buses, train and Metro Rigshospitalet 3A Dag Hammerskjölds Allé Ryesgade Blegdamsvej Kristianiagade 26 1A 15 Østbanegade Øster Søgade Møllegade Nørre Allé Østerport st. 3A Folke Bernadottes Allé Sortedam Dossering 40 14 Den Lille Havfrue Blegdamsvej Øster Farimagsgade Little Mermaid Læssøesgade Fredensbro Kastellet Guldbergsgade Copenhagen Citadel 6A 42 43 Webersgade Møllegade Ryesgade Peter Fabers Gade Skt. Hans Gade 184 185 Østre Anlæg Stockholmsgade Sølvgade173E Nørrebrogade Store Kongensgade Elmegade 150S Hirschsprungs Samling Hirschsprung’s Collection 26 Nyboder Grønningen 3A 5A Stokhusgade Suensonsgade 6A Fælledvej 1A 184 185 Statens Museum 350S 15 Sølvgade for Kunst 1A Nordre Sortedam Dossering Danish National 173E 150S e Gernersgade 15 Toldbod NørrebrogadeRavnsborggade Gallery Griffenfeldsgade Øster Voldgade Øster Søgade Skt. Pauls Gade Esplanaden Baggesensgade Olfert Fischers Gade 3A Dr. Bartholinsgade Rigensgade Stengade Lo Botanisk Have onprinsessgad 14 40 42 43 5A uises Bro Botanic Garden Sølvgade Kr Fredericiagade 350S Klerkegade Øster Farimagsgade 26 15 Kunstindustrimuseet 901 Gothersgade 1A Frederiksborggade Museum of Art & Design 902 15 50S Adelgade 1A Korsgade Blågårdsgede 73E 1 1 42 43 Store Kongensgade Rosenborg Slot Borgergade Bredgade Gartnergade Wesselsgade Vendersgade 184 185 Rosenborg Casttle Amaliegade Arbejdermuseet 6A Øster Voldgade 26 5A Rømers- 14 gade Toldbodgade 350S Kongens Have Marmorkirken Smedegade Peblinge Dossering Dronningens TværgadeFrederik’s Church Nørreport st. Kronprinsessegade Davids Samling 350S 11 Gothersgade The David 26 Amalienborg Amalienborg Casttle Åboulevard Åbenrå Collection 11 11 Holmen 11 350S 26 12 66 69 Rosenborgg. Nørre Søgade Israels 66 Ahlefeldtsgade 11 Plads Filminstituttet Hausergade 11 Borgergade VognmagerDanish gade Film InstituteAdelgade Nansensgade Landemærket Linnésg. Kul- 11 350SGothersgade Amaliegade Fiolstræde 15Palægade 26 Skt. -

Und Tschüß Stilllegungsdaten Straßenbahnstrecken Europa Seite 1 DK 02 Kopenhagen

... und tschüß Stilllegungsdaten Straßenbahnstrecken Europa Seite 1 DK 02 Kopenhagen 22.04.1972 1435 mm SL 5 Husum – Bronshoj – Bellahoj Abzw. - Frederikssundsvej - Norrebro Bf - Norrebro, Depot - Norrebro, Runddel – Norrebrogade - Norreport – Norregade - Stormgade - Langebro– Holmbladsgate Abzw / Schleife – Öresundsvej (Schleife) – Backersvej - Sundby Depot (Ost) – Formosavej 16.10.1971 Obus OBL 27 A, Soborg Torg – Vangede Str – Kildegards Pl. – Hellerupvejen – 27 B Hellerup – Depot – Strandvejen – Charlottenlund Abzw. (Einfahrt Schleife: 27 A / 27 B ) – Charlottenlund – Strandvejen - Klampenborg – Ordrup – Ordrupvej – Femvejen – Charlottenlund Bf. – Charlottenlund Abzw. 25.04.1971 1435 mm SL 7 Norreport – Gothersgade - Kongens Nytorv 26.04.1970 1435 mm SL 16 Emdrupvej – Bispebjerg Abzw + Schleife – Frederiksborgvej - Norrebro Bf 26.04.1970 1435 mm SL 16 Norreport - Norre Voldgade - Radhuspl – Hauptbahnhof – Vesterbrogade - Istedgade – Enghaveplads - Enghave – Toftegardspl. 19.10.1969 1435 mm SL 2 Bronshoj – Hulgardsvej – Godthabsvej – Godthabsvej/N. Fasanvej (Aerovej) Godthabsvej/Jagtvej – Godthabsvej/H. C. Orstedsvej - Radhuspl – Stormgade – Knippelsbro Abzw. - Holmbladsgade – Amagerbrogade - Sundby Depot (West) – Sundbyvester Plads. 27.04.1969 1435 mm SL 6 Ryparken – Lyngbyvej Bf – H. Knudsens Pl – Vibenshus, Runddel – Oster Allee - Trianglen – Blegdamsvej Depot – Osterport Bf – Kongens Nytorv – Knippelsbro Abzw, 27.04.1969 1435 mm SL 6 Hauptbahnhof – Vesterbrogade – Slotskroen – Langgade - Valby Bf – Valby Depot – Alholm Plads 13.10.1968 1435 mm SL 10 Istedgade Abzw. Hauptbahnhof Süd - Stormgade 13.10.1968 1435 mm SL 10 Kongens Nytorv – Solvgade – Tagensvej – Tagensvej/Blegdamsvej – Tagensvej/Jagtvej – Bispebjerg Abzw + Schleife 13.10.1968 1435 mm SL 16 Enghave – Vestre Kirkegard 28.04.1968 1435 mm SL 3 Strandboulevard – Trianglen – Blegdamsvej – Blegdamsvej/Tagensvej - H. C. Orsteds Vej/Godthabsvej - H. C. Orsteds Vej/Gl. Kongevej - H. -

Exploring Amsterdam by Tram

Exploring Amsterdam by tram Trams are a convenient and simple way to get around Amsterdam. But even more than just a way to get from A to B, a tram ride can be a sightseeing tour in itself, taking in some of the city’s best sights and attractions along the way. There are three tram routes (1, 2 and 5) that travel up and down a central ‘spine’ of Amsterdam, from Centraal Station to Museumplein and back again. Tram #1, #2 and #5 Stop: Centraal Station As Amsterdam’s main transport hub, Centraal Station is a familiar starting point for most visitors to the city. The spectacular building opened its doors in 1889, and was designed by architect Pierre Cuypers, who also designed the Rijksmuseum. What to see and do: • Check out the vintage shops, hip cafes and arty design stores of vibrant Haarlemmerstraat to the west • Take the free ferry from behind Centraal Station to trendy Amsterdam Noord • Explore Oosterdok to the east of the station, making sure to take in the view of the city from NEMO’s rooftop terrace and stop for a drink at Hannekes Boom. From Centraal Station, the tram heads south down Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, once the city’s defence line (‘burgwal’ means ‘bastion wall’). Stop: Nieuwezijds Kolk Continue south, passing behind the impressive Nieuwe Kerk on your left. Despite being called ‘New Church’, this imposing monument actually dates from the 15th century and is only ‘new’ in relation to the nearby Oude Kerk (old church) which was deemed too small to be the parish church of Amsterdam’s expanding population in 1408. -

Københavnske Gader Og Sogne I 1890 RIGSARKIVET SIDE 2

HJÆLPEMIDDEL Københavnske gader og sogne i 1890 RIGSARKIVET SIDE 2 Københavnske gader og sogne Der står ikke i folketællingerne, hvilket kirkesogn de enkelte familier hørte til. Det kan derfor være vanskeligt at vide, i hvilke kirkebøger man skal lede efer en familie, som man har fundet i folketællingen. Rigsarkivet har lavet dette hjælpemiddel, som sikrer, at I som brugere får lettere ved at finde fra folketællingen 1890 over i kirkebøgerne. Numrene i parentes er sognets nummer. RIGSARKIVET SIDE 3 Gader og sogne i København 1890 A-B Gade Sogn Aabenraa .............................................................................. Trinitatis (12) Abel Cathrinesgade .............................................................. Sankt Matthæus (58) Abildgårdsgade .................................................................... Sankt Jakobs (23) Absalonsgade ....................................................................... Sankt Matthæus (58) Adelgade ............................................................................... Trinitatis (12) Adelgade ............................................................................... Sankt Pauls (24) Adilsvej ................................................................................. Frederiksberg (64) Admiralgade ......................................................................... Holmens (21) Agnetevej .............................................................................. Frederiksberg (64) Ahlefeldtsgade .................................................................... -

Oversigt Over Legepladser Der Skal Inspiceres

BILAG 4: Oversigt over legepladser der skal inspiceres Ved henvendelse er det muligt at få tilsendt et kort over legepladsernes placering nummer navn på legeplads lokalitet/ adresse bemandet INDRE BY 9 3 Langelinieanlægget ved Nordre Toldbod 4 Østre Anlæg Stockholmsgade 24 9 5 Østre Anlæg Sølvtorvet 10 6 Gammel Vagt Gammel Vagt 5 12 9 Ørstedsparken Overfor Ahlefeldtsgade 16 4 10 Sankt Annæ Plads udfor Skt Annæs Plads 1-13 10 13 Nikolaj Plads Udfor Nikolaj Plads 5-11 11 14 Christianshavns Vold På Panterens Bastion 8 15 Christianshavns Vold På Elefantens Bastion B 8 6 ØSTERBRO 10 7 16 Kildevældsparken Vognmandsmarken 69 B 85 17 Musholmsgade Musholmsgade Legegade 18 Svendborggade Svendborggade/ Nyborggade 22 Bopa Plads Bopa Plads 23 Silkeborg Plads Silkeborg Plads 26 Livjægergade Rosenvængets Allé/ Livjægergade 27 Fælledparken Sansehaven ved Trianglen 28 Blegdamsremisen (indendørs legeplads) Blegdamsvej 132A B 132 Amorparken Tagensvej/ Nørre Allé 30 Fredens Park Fredensgade/ Søpassagen NØRREBRO 12 31 Folkets Park Stengade 50 33 Balders Plads ved Balders Plads 35 Guldbergs Plads Guldbergs Plads 36 Allersgade mellem Allersgade og Thorsgade 37 Bispeengen Hillerødgade 23B B 39 Udbygade Guldbergsdade/ Sjællandsgade/ Udbygade 41 Hans Tavsens Park vest Hans Tavsensgade 40 B 43 Sankt Hans Gade Skant Hans Gade 3-5 44 Hans Tavsens Park Øst Hans Tavsensgade 40 B 45 Blågårds Plads vestlige ende af Blågårds Plads 46 Wesselsgade Wesselsgade 12-16 B 130 Banana Park Nannasgade 6 VESTERBRO, KONGENS ENGHAVE 4 47 Saxoparken Saxoparken 48 Skydebanehaven Mathæusgade -

Busser Storkøbenhavn

Constantia Vandtårnsvej Tog, metro, C-, A- og S-busser i Storkøbenhavn Annasvej Trains, metro, C, A and S buses in Greater Copenhagen A.N.Hansensens Allé ole Lille Strandvej orv Søborg Sk Vandtårnsvej Søborg T Søborg Hovedgade Onsgårdsvej Hellerup St. Erik Bøghs Allé zone e Gladsaxevej 30 e Hellerupvej Sydmarken Møllevej Gladsax 1 osevej Dyssegårdsvej Dyssegård St. Lyngbyvej50S Callisensvej Gyngem Høje Gladsax Høje Gladsaxevej Tuborg Boulevard Gladsaxevej Færgehavn Nord Gl. Vartov Vej uborgvej Juni Allé T A Emdrup 1 Strandøre 7 Torv 2 0S 00S g Strandvejen 2 Tingbjerg 25 Frederiksborgvej Strandvænget Stavnsbjerg Allé Mørkhøjvej Bispebjer 25 Fuglegavl Parkallé Grundtvigs Kirke Emdrup St. 27 Høje Gladsaxe Vej Gladsaxe Høje Ryparken St. Arkaderne Grundvig’s Church Ocean Kaj Cruise Ships zone Gavlhusvej Tingbjerg Kirke Svanemøllen St. A Nørre Gymnasium 2 Tingbjerg Skole Bispebjerg Ocean Kaj - Østerport St. - Nørreport St. Torv 25 Tagensvej Hans Knudsens Terrasserne Hareskovvej 6A Operates only from May to September 31 25 Plads Thomas 0S uborgvej Laubs Nygårdsvej zone T S Gade zone Husum Torv Voldparken Skole 2 1 Mellemvangen Kildevælds Husumvej Bispebjerg Hospital 50 Apark 1 4 5C 350S 200S 5C 350S Husumvold Kirke A Åkandevej Lersø Parkallé Østerbrogade Svendborg- HaraldsgadeNygårdsvej 1 Lyngbyvej en Jagtvej Lygten Skt. Kjeld gade Frederikssundvej Aldersrogade Plads - 8A ej Brønshøj Kirke Bispebjerg St. e Lyngbyvej/ s Kobbelvænget Veksøv Århusgade Brønshøj Torv Serridslevvej Glasvej Astrupvej Hulgårds Plads Bellahøj Haraldsgade Hyrdevangen -

Unikt Kontordomicil ”Ved Trianglen”

LEJEPROSPEKT Unikt kontordomicil ”Ved Trianglen” Kontorlejemål på 4.644 m² af højeste kvalitet i meget spændende rammer med højloftet lagerhal, taghave, tagterrasse og Metro lige til døren Klar til indflytning fra juni 2021 BLEGDAMSVEJ 124/RYESGADE 113 2100 KØBENHAVN Ø Trianglen Karma Sushi Trianglen Metro Fælledparken Røde Kors Marathon Sport Blegdamsvej 124/ Ryesgade 113 Den Danske Frimurerorden Irma Niels Bohr Instituttet Den Franske Cafe Joe And the Juice Eksklusiv beliggenhed på Østerbro Det bliver næppe mere centralt på Østerbro med udsigt til Fælledparken, Sortedams Sø Famo Dag H Trianglen Metrostation for foden af ejendommen og 200 meter til Søerne. Nærområdet byder på alt hvad hjertet begærer af cafémiljø og pulserende handel i krydsfeltet mellem Østerbrogade og Nordre Frihavnsgade. Ligeledes er lejemålet tæt forbundet med den trafikale infrastruktur ind og ud af byen via Lyngbyvej. Parken ligger ganske tæt på lejemålet med rigeligt af parkeringsmuligheder. Fælledparken Trianglen Metro Caféer Holmens Kirkegaard 50 m 50 m 50 m 3 | LEJEPROSPEKT | SAG 290455 | Rev. nr. E2038 | Blegdamsvej 124/Ryesgade 113 | PARKERINGSKORT PARKERINGSANÆG Parkeringsmuligheder GUNNAR NU HANSENS PLADS Mulighed for private p-pladser 850 METER lige overfor lejemålet Pris: 1.200,- pr. plads/md. 10 faste p-pladser ved PARKEN ca. 500 meter fra lejemålet Pris: 1.500,- pr. plads/md. Mere end 1.000 offentlige p-pladser under 250 m. fra PARKEN 10 P-pladser til udlejning lejemålet. 1.500 kr. / md. + moms Blå P-zone, 14 kr./time, 500 METER hverdage 8-18 401 PARKERINGPLADSER 500 METER ØSTER ALLE < 700 METER FRA BLEGDAMSVEJ 124 PARKERING PÅ NORDRE FRIHAVNSGADE < 500 METER FRA BLEGDAMSVEJ 124 TRIANGLEN 619 PARKERINGSPLADSER PÅ BLEGDAMSVEJ < 250 METER FRA BLEGDAMSVEJ 124 PARKERING PÅ RYESGADE < 250 METER FRA BLEGDAMSVEJ 124 4 | LEJEPROSPEKT | SAG 290455 | Rev.