Shaping the System. National Park Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Spiritual Program Fall 2009

Saturday, September 26, 2009 • 7:30 p.m. Asbury United Methodist Church • 1401 Camden Avenue, Salisbury Comprised of some of the finest voices in the world, the internationally acclaimed ensemble offers stirring renditions of Negro spirituals, Broadway songs and other music influenced by the spiritual. This concert is sponsored by The Peter and Judy Jackson Music Performance Fund;SU President Janet Dudley-Eshbach; Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs Diane Allen; Dean Maarten Pereboom, Charles R. and Martha N. Fulton School of Liberal Arts; Dean Dennis Pataniczek, Samuel W. and Marilyn C. Seidel School of Education and Professional Studies; the SU Foundation, Inc.; and the Salisbury Wicomico Arts Council. THE AMERICAN SPIRITUAL ENSEMBLE EVERETT MCCORVEY , F OUNDER AND MUSIC DIRECTOR www.americanspiritualensemble.com PROGRAM THE SPIRITUAL Walk Together, Children ..........................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Jacob’s Ladder ..........................................................................................................arr. Harry Robert Wilson Angelique Clay, Soprano Soloist Plenty Good Room ..................................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Go Down, Moses ............................................................................................................arr. Harry T. Burleigh Frederick Jackson, Bass-Baritone Is There Anybody Here? ....................................................................................................arr. -

990-PF and Its Instructions Is at /Form990pf

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491316011664 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 0- Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. By law, the 2013 IRS cannot redact the information on the form. Department of the Treasury 0- Information about Form 990-PF and its instructions is at www.irs.gov /form990pf . Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2013 , or tax year beginning 01-01-2013 , and ending 12-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 22-6029397 O/o MARGARET H EINHORN CFO&TRE Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite 6 ieiepnone number (see instructions) PO BOX 2316 Suite (609) 452-8701 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here F PRINCETON, NJ 085432316 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here F r-Final return r-Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation E If private foundation status was terminated H C heck type of organization F Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F_ Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part II, col. -

Shouse, Kay (Medal of Freedom)” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 45, folder “Shouse, Kay (Medal of Freedom)” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON May4, 1976 Nancy: I did want to talk to Mrs. Ford about the attached. I do not like to send something like this direct and would be pleased to refer it to another office if she feels that would be more appropriate. Mrs. Shouse just happens to be a most outstanding per son. PILENE CENTER/WOLr TRAP rARM PARK roR THE PERrORMING ARTS THE WOLF TRAP FOUNDATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Mrs. Gerald R. Ford Honorary Chairman Mrs. Jouett Shouse Founder J. William Middendorf II Chairman Rodney Weir Markley, Jr. Vice-Chairman Hobart Taylor, Jr. April 20, 1976 Vice-Chairman Bradshaw Minte.1er Secretary Douglas R. Smith Mrs. Gerald R. Ford Treasurer The White House Ralph E. Becker Washington, D. C. -

VIRGINIA the Birthplace of a Nation

VIRGINIA The Birthplace of a Nation Created for free use in the public domain American Philatelic Society ©2010 • www.stamps.org Financial support for the development of these album pages provided by Mystic Stamp Company America’s Leading Stamp Dealer and proud of its support of the American Philatelic Society www.MysticStamp.com, 800-433-7811 Virginia Discovered The history of Virginia begins long before the Englishmen set foot in the New World. The land had been inhabited by Native Americans for several thousand years. The Algonquian, Iroquoian, Siouan all resided along the Central Atlantic coast. After the discovery of the New World, England, the Dutch Republic, France, Portugal, and Spain all attempted to establish New World colonies. A Spanish exploration party had come to the lower Chesapeake Bay region of Virginia about 1560 and met the Native Americans living on the Virginia Peninsula. The first English settlers arrived at Jamestown in 1607. Jamestown Exposition Issue Jamestown Exposition Issue Founding of Jamestown, 1607 Captain John Smith 1907 • Scott 329 1580–1631 1907 • Scott 328 Jamestown was founded in 1607 by a group of 104 English “gentlemen” who were sent by King James I to John Smith is remembered as the leader of the first English search for gold and a water route to the Orient. Disease, settlement in Virginia. Having endured the four month famine, and attacks from the Algonquians, took a toll on journey (from December 1606 to April 1607) to the New the initial population. However, with the determination World, the colonists only survived because of Smith’s “He of John Smith and the trading with Powhatan (chief of who does not work, will not eat” policy. -

2005/2007 Catalog

2005/2007 Catalog Wheaton College | Norton, Massachusetts www.wheatoncollege.edu/Catalog2005/2007 catalog 2 College Calendar Fall Semester 2005 Fall Semester 2006 New Student Orientation Aug. 27–30 New Student Orientation Aug. 26–Aug. 29 Upperclasses Return August 29 Classes Begin August 30 Classes Begin August 3 Labor Day (no classes) September 4 Labor Day September 5 October Break October 9–0 October Break October 0– Mid-Semester October 8 Mid-Semester October 9 Course Selection Nov. 6–0 Course Selection Nov. 7– Thanksgiving Recess Nov. 22–26 Thanksgiving Recess Nov. 23–27 Classes End December 8 Classes End December 9 Review Period Dec. 9–0 Review Period Dec. 0– Examination Period Dec. –6 Examination Period Dec. 2–7 Residence Halls Close Residence Halls Close (9 p.m.) December 6 (9 p.m.) December 7 Winter Break and Winter Break and Internship Period Dec. 6–Jan. 23, 2007 Internship Period Dec. 7–Jan. 24, 2006 Spring Semester 2007 Spring Semester 2006 Residence Halls Open Residence Halls Open (9 a.m.) January 23 (9 a.m.) January 24 Classes Begin January 24 Classes Begin January 25 Mid–Semester March 9 Mid–Semester March 8 Spring Break March 2–6 Spring Break March 3–7 Course Selection April 9–3 Course Selection April 0–4 Classes End May 4 Classes End May 5 Review Period May 5–6 Review Period May 6–7 Examination Period May 7–2 Examination Period May 8–3 Commencement May 9 Commencement May 20 Fall Semester Deadlines 2006 Fall Semester Deadlines 2005 Course registration Course registration concludes September 8 concludes September 9 Last -

National Park Service National Capital Region Administrative History, 1952-2005

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY, 1952-2005 Final Report Prepared by Robinson & Associates, Inc. June 6, 2008 National Capital Region Administrative History Final Report Robinson & Associates, Inc. June 6, 2008 Page 1 ______________________________________________________________________________________ NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 INTRODUCTION Purpose 9 Methodology 10 Executive Summary 12 CHAPTER I: ORGANIZATION OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Administration 17 Planning 24 Design and Construction 26 Maintenance 30 Museum Collections Management 32 Illustrations 34 CHAPTER II: OUTSIDE THE SERVICE: PHILANTHROPY, PARTNERS, AND CONCESSIONS Philanthropy 43 Partners 44 Interagency Cooperation 49 Concessions 50 Illustrations 53 CHAPTER III: THE NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION AND THE POST-WORLD WAR II GROWTH OF METROPOLITAN WASHINGTON Growth of the Region 55 The Commission of Fine Arts and the National Capital Planning Commission 56 NCR and Metropolitan Transportation Needs 58 Mission 66 65 The Bicentennial 73 Illustrations 77 CHAPTER IV: NATURAL RESOURCES Natural Resources Management in the National Park Service, 1952-2005 83 Natural Resources in the National Capital Region 87 The Potomac and Anacostia Rivers 91 Interpretation of Natural Resources 94 Lady Bird Johnson’s Beautification Program 99 Illustrations 104 National Capital Region Administrative History Final Report Robinson & Associates, Inc. June 6, 2008 Page 2 ______________________________________________________________________________________ -

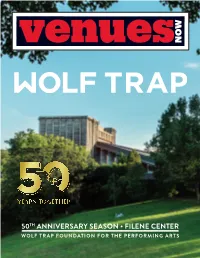

07-21 Wolftrap Spotlight

50TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON • FILENE CENTER WOLF TRAP FOUNDATION FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS CELEBRATING ARTISTS OVER THE PAST HALF CENTURY STING MARY J BLIGE MARC ANTHONY THE AVETT BROTHERS MILES DAVIS COMMON AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE HALSEY BACKSTREET BOYS LEON BRIDGES BRANDI CARLILE MARY CHAPIN CARPENTER JUDY COLLINS HARRY CONNICK, JR. JOAN BAEZ CROSBY, STILLS & NASH SHERYL CROW CELINE DION DAVID BYRNE EARTH, WIND & FIRE ELLA FITZGERALD RENÉE FLEMING ARETHA FRANKLIN PHISH JOSH GROBAN HEART DON HENLEY WHITNEY HOUSTON JENNIFER HUDSON NORAH JONES KESHA JUANES CAROLE KING RAY LAMONTAGNE RICKY MARTIN NATHANIEL RATELIFF & THE NIGHT SWEATS NATIONAL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WILCO SUFJAN STEVENS KEITH URBAN ONEREPUBLIC JOHN PRINE RIVERDANCE ROBYN PRINCE ROYCE JILL SCOTT PAUL SIMON YO-YO MA ALANIS MORISSETTE LENNY KRAVITZ AND MORE BOOKINGS: SARA BEESLEY WOLFTRAP.ORG 703.255.1902 • [email protected] JULY 2021 VOLUME 20 | NUMBER 7 VENUESNOW.COM LIGHT FANTASTIC LED GIVES VENUES A NEW WAY TO SHINE The Arts, Naturally COURTESY WOLF TRAP TRAP WOLF COURTESY 24 JULY 2021 ARTS CATHEDRAL: The Filene Center has 7,028 seats and is the primary venue at Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts. WOLF TRAP MARKS HALF A CENTURY AND GEARS UP FOR THE FUTURE BY LISA WHITE he pandemic isn’t the only seemingly insur- mountable challenge that the Wolf Trap Foundation for the Performing Arts in Vienna, Virginia, has Tfaced in its 50 years of operation. In April 1982, after its Filene Center venue burned to the ground, patrons stepped up not only to financially support a true- to-the-original rebuild but also to create a temporary structure that would ensure Wolf Trap’s season of 77 performances went on as planned. -

Leadership Lessons of the White House Fellows

“Leadership Lessons of White House Fellows takes a close look at the young Americans who have participated in this program and at their interesting and absorbing stories and insights.” —The Honorable Elaine L. Chao, former United States Secretary of Labor, President and CEO of United Way of America, Director of the Peace Corps “The lessons I learned as a White House Fellow have informed my leadership principles and influenced me deeply throughout my career. In this powerful and insightful book, Garcia shows readers how to use these same lessons within their lives.” —Marshall Carter, Former Chairman and CEO, State Street Bank and Trust; Senior Fellow, Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government “This is a reflective and compelling account of how a remarkable program shaped the lives of many of America’s best leaders – and continues to shape the leaders that we’ll need in our future.” —Clayton M. Christensen, Robert & Jane Cizik Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School; bestselling author of Innovator’s Prescription, Disrupting Class, and The Innovator’s Dilemma “This book is full of illuminating leadership lessons that teach and inspire.” —Roger B. Porter, IBM Professor of Business and Government, Harvard University “Garcia has done a tremendous service by writing this book. There is abso- lutely no better training ground for the next generation of leaders than the White House Fellows Program.” —Myron E. Ullman, III, Chairman and CEO of J.C. Penney and Chairman of the National Retail Federation “Charlie Garcia’s book recounts the stories of Americans who have given their lives to public service, and explains in their own words the “how” that made them effective servant leaders. -

Event Program Here

27th Anniversary Women’s International Center Living Legacy Awards May 5 2012 Women’s International Center Living Legacy Awards Welcome! Honoring, Encouraging and Educatng Women for More tan a Quartr Century... Since its founding in 1982, Women’s Intrnatonal Centr (WIC) has demanded excelence of itself and al tose affiliatd wit te organizaton. Beginning in 1984, WIC has publicly honored excelence, accomplishment, philantropy and humanitarianism trough te Living Legacy Awards. From tat glorious beginning t tday, over two hundred of te world’s exceptonal contibutrs have acceptd te Living Legacy Award. Te Award has been presentd t presidents, heads of stat, first ladies, educatrs, film and stage actrs, scientsts, atlets, business and military leaders, politcal personalites, and oter remarkable individuals and organizatons contibutng t te beterment of oters. Please join us tday Saturday May 5, 2012, in celebratng te accomplishments of tis year’s Living Legacy Award Honorees, in support of our educatonal scholarship fnds. We tank te Crowne Plaza Hanalei and teir Supportve Team. Women’s Intrnatonal Centr (501c3) A non-profit service and educaton foundaton Fed Tax ID 95-3806872 CA non-profit #D113-1510 PO Box 669 Rancho Santa Fe, CA 92067-0669 Phone & Fax: 858 759 3567 websit www.wic.org Gloria: [email protected] (please cc [email protected] ) CEO: [email protected] CFO: [email protected] Cover Photos: Living Legacy Honorees Top: Lucy C Lin, Ashley Gardner, Mary B. Maschal Tribute, Velina Hasu Houston, Ph.D., Mary Lyons Ph.D., Chairman Heng-Tzu Hsu, Thomas Del Ruth, ASC, Patricia West Del Ruth, David Straus Middle: Mary Cain Youngflesh, June Foray WIC Leadership: Gloria Lane President, Bridget McDonald CEO, Sally B. -

Sonya Levien Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf558003r5 No online items Sonya Levien Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Gayle M. Richardson, January 31, 1997, revised November 10, 2010. Initial cataloging and biography Carolyn Powell, November 1994. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2017 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Sonya Levien Papers: Finding Aid mssHM 55683-56785, mssHM 74388 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Sonya Levien Papers Dates (inclusive): 1908-1960 Collection Number: mssHM 55683-56785, mssHM 74388 Creator: Levien, Sonya, 1888?-1960. Extent: 1,181 pieces + ephemera and awards in 35 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Hollywood screenwriter Sonya Levien (1888?-1960), including screenplays, literary manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, awards and ephemera. There is also material in the collection related to Levien's early involvement with the Suffrage movement, both in America and England, as well as material recounting life in England and surviving the Blitz in World War Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

Wheaton College Catalog 2001-2003 (Pdf)

Wheaton 2001 – 2003 CATALOG WHEATON COLLEGE Norton, Massachusetts www.wheatoncollege.edu/Catalog 2 College Calendar Fall Semester 2001–2002 New Student Orientation Sept. 1–Sept. 4, 2001 Labor Day September 3 Upperclasses Return September 3 Classes Begin September 5 October Break October 8–9 Mid-Semester October 24 Course Selection Nov. 5–14 Thanksgiving Recess Nov. 21–25 Classes End December 11 Review Period Dec. 12–13 Examination Period Dec. 14–19 Residence Halls Close (8:00 p.m.) December 19 Winter Break and Internship Period Dec. 20 – Jan. 27, 2002 Spring Semester Residence Halls Open (9:00 a.m.) January 27, 2002 Classes Begin January 28 Mid–Semester March 8 Spring Break March 11–15 Course Selection April 15–22 Classes End May 3 Review Period May 4–5 Examination Period May 6–10;13–14 Commencement May 18 First Semester Deadlines, 2001–2002 Course registration concludes September 13 Last day to declare pass/fail registration September 27 Mid-semester grades for freshmen due (Registrar’s Office) October 24 Last day to drop course without record November 2 January study scholarship application (Advising Center) November 2 Registration deadline for spring courses (Registrar’s Office) November 14 Spring Semester Deadlines, 2001–2002 Application deadline for 11 College Exchange (Advising Center) February 1 Course registration concludes (Registrar’s Office) February 5 Last day to declare pass/fail registration February 22 Mid-semester grades for freshmen due (Registrar’s Office) March 8 Last day to drop a course without record March 22 Application deadlines for off-campus study—fall and 2002-03 programs; Wheaton graduate scholarships/fellowships and summer school scholarships (Advising Center) April 1* Registration deadline for fall courses, 2002 (Registrar’s Office) April 22 *Check with the Filene Center for individual JYA or domestic study programs which may vary. -

Faye Glenn Abdellah 1919 - • As a Nurse Researcher Transformed Nursing Theory, Nursing Care, and Nursing Education

Faye Glenn Abdellah 1919 - • As a nurse researcher transformed nursing theory, nursing care, and nursing education • Moved nursing practice beyond the patient to include care of families and the elderly • First nurse and first woman to serve as Deputy Surgeon General Bella Abzug 1920 – 1998 • As an attorney and legislator championed women’s rights, human rights, equality, peace and social justice • Helped found the National Women’s Political Caucus Abigail Adams 1744 – 1818 • An early feminist who urged her husband, future president John Adams to “Remember the Ladies” and grant them their civil rights • Shaped and shared her husband’s political convictions Jane Addams 1860 – 1935 • Through her efforts in the settlement movement, prodded America to respond to many social ills • Received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 Madeleine Korbel Albright 1937 – • First female Secretary of State • Dedicated to policies and institutions to better the world • A sought-after global strategic consultant Tenley Albright 1934 – • First American woman to win a world figure skating championship; triumphed in figure skating after overcoming polio • First winner of figure skating’s triple crown • A surgeon and blood plasma researcher who works to eradicate polio around the world Louisa May Alcott 1832 – 1888 • Prolific author of books for American girls. Most famous book is Little Women • An advocate for abolition and suffrage – the first woman to register to vote in Concord, Massachusetts in 1879 Florence Ellinwood Allen 1884 – 1966 • A pioneer in the legal field with an amazing list of firsts: The first woman elected to a judgeship in the U.S. First woman to sit on a state supreme court.