2005/2007 Catalog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

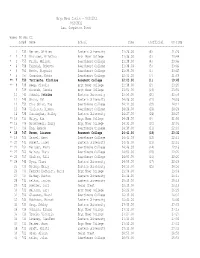

Bryn Mawr Invite - 9/2/2011 9/2/2011 Last Completed Event

Bryn Mawr Invite - 9/2/2011 9/2/2011 Last Completed Event Women 5k Run CC Comp# Name School Time UnOfficial UO TIME =================================================================================================================== 1 732 Kerner, Whitney Eastern University 21:26.00 {8} 21:26 * 2 710 Kronauer, Kristina Bryn Mawr College 21:36.00 {3} 20:44 * 3 755 Frick, Melissa Swarthmore College 21:38.00 {4} 20:46 * 4 758 Hammond, Rebecca Swarthmore College 21:38.03 {5} 20:46 * 5 751 Beebe, Stepanie Swarthmore College 21:39.00 {6} 20:47 * 6 757 Gonzalez, Katie Swarthmore College 22:01.00 {7} 21:09 ** 7 750 Torriente, Klarisse Rosemont College 22:03.00 {1} 19:45 ** 8 708 Keep, Claudia Bryn Mawr College 22:38.00 {2} 20:20 9 709 Kosarek, Cassie Bryn Mawr College 23:51.00 {19} 23:51 10 743 Schmid, K atrina Eastern University 23:59.00 {20} 23:59 11 745 Wrona, Val Eastern University 24:06.00 {21} 24:06 12 752 Cina-Sklar, Zoe Swarthmore College 24:11.00 {22} 24:11 13 768 Violante, Ximena Swarthmore College 24:24.00 {23} 24:24 14 728 Cunningham, Hailey Eastern University 24:27.00 {24} 24:27 ** 15 716 Wiley, Kim Bryn Mawr College 24:28.00 {9} 21:59 ** 16 704 Brownawell, Emily Bryn Mawr College 24:35.00 {10} 22:06 ** 17 754 Eng, Amanda Swarthmore College 24:39.00 {11} 22:10 * 18 747 Brown, Lisanne Rosemont College 24:41.00 {18} 23:32 ** 19 766 Saarel, Emma Swarthmore College 24:41.03 {12} 22:11 ** 20 741 Rupert, Josey Eastern University 24:46.00 {13} 22:16 ** 21 761 Marquez, Mayra Swarthmore College 24:46.03 {14} 22:16 ** 22 763 Naiman, Thera Swarthmore -

The Ursinus Weekly, February 15, 1967

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Ursinus Weekly Newspaper Newspapers 2-15-1967 The rsinU us Weekly, February 15, 1967 Lawrence Romane Ursinus College Herbert C. Smith Ursinus College Mort Kersey Ursinus College Frederick Jacob Ursinus College Lewis Bostic Ursinus College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/weekly Part of the Cultural History Commons, Higher Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation Romane, Lawrence; Smith, Herbert C.; Kersey, Mort; Jacob, Frederick; and Bostic, Lewis, "The rU sinus Weekly, February 15, 1967" (1967). Ursinus Weekly Newspaper. 196. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/weekly/196 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ursinus Weekly Newspaper by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .... rstnus Volume LXVI WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 1967 Number 6 Lorelei, t he Drifters, and Winter I. F. Highlight February Social Events Winter Weekend Approaches Rock and Roll Comes to Ursinus Tomorrow evening at 8 :00 the third annual l.F.-I.s. Win On Thursday, February 16, the Agency will present the ter \Veekend will again dismember the myth of Ursinus as a DRIFTERS in concert at Ursinus. A group well known a suitcase college. In cooperation with the Agency this year mong those who enjoy rock and roll, the Drifters have been the Inter-Fraternity Inter-Sorority Council is beginning their one of America's most popular vocal groups since 1955. -

American Spiritual Program Fall 2009

Saturday, September 26, 2009 • 7:30 p.m. Asbury United Methodist Church • 1401 Camden Avenue, Salisbury Comprised of some of the finest voices in the world, the internationally acclaimed ensemble offers stirring renditions of Negro spirituals, Broadway songs and other music influenced by the spiritual. This concert is sponsored by The Peter and Judy Jackson Music Performance Fund;SU President Janet Dudley-Eshbach; Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs Diane Allen; Dean Maarten Pereboom, Charles R. and Martha N. Fulton School of Liberal Arts; Dean Dennis Pataniczek, Samuel W. and Marilyn C. Seidel School of Education and Professional Studies; the SU Foundation, Inc.; and the Salisbury Wicomico Arts Council. THE AMERICAN SPIRITUAL ENSEMBLE EVERETT MCCORVEY , F OUNDER AND MUSIC DIRECTOR www.americanspiritualensemble.com PROGRAM THE SPIRITUAL Walk Together, Children ..........................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Jacob’s Ladder ..........................................................................................................arr. Harry Robert Wilson Angelique Clay, Soprano Soloist Plenty Good Room ..................................................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Go Down, Moses ............................................................................................................arr. Harry T. Burleigh Frederick Jackson, Bass-Baritone Is There Anybody Here? ....................................................................................................arr. -

America's Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb on Japan Joseph H

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 America's decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan Joseph H. Paulin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Paulin, Joseph H., "America's decision to drop the atomic bomb on Japan" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 3079. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICA’S DECISION TO DROP THE ATOMIC BOMB ON JAPAN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Inter-Departmental Program in Liberal Arts By Joseph H. Paulin B.A., Kent State University, 1994 May 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………...………………...…….iii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………...………………….1 CHAPTER 2. JAPANESE RESISTANCE………………………………..…………...…5 CHAPTER 3. AMERICA’S OPTIONS IN DEFEATING THE JAPANESE EMPIRE...18 CHAPTER 4. THE DEBATE……………………………………………………………38 CHAPTER 5. THE DECISION………………………………………………………….49 CHAPTER 6. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………..64 REFERENCES.………………………………………………………………………….68 VITA……………………………………………………………………………………..70 ii ABSTRACT During the time President Truman authorized the use of the atomic bomb against Japan, the United States was preparing to invade the Japanese homeland. The brutality and the suicidal defenses of the Japanese military had shown American planners that there was plenty of fight left in a supposedly defeated enemy. -

College/University Visit Clusters

COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY VISIT CLUSTERS The groupings of colleges and universities below are by no means exhaustive; these ideas are meant to serve as good starting points when beginning a college search. Happy travels! BOSTON/RHODE ISLAND AREA Large: Boston University University of Massachusetts at Boston Northeastern University Medium: Bentley University (business focus) Boston College Brandeis University Brown University Bryant College (business focus) Harvard University Massachusetts Institute of Technology Providence College University of Massachusetts at Lowell University of Rhode Island Suffolk University Small: Babson College (business focus) Emerson College Olin College Rhode Island School of Design (art school) Salve Regina University Simmons College (all women) Tufts University Wellesley College (all women) Wheaton College CENTRAL/WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS Large: University of Massachusetts at Amherst/Lowell Medium: College of the Holy Cross Worcester Polytechnic Institute Small: Amherst College Clark University Hampshire College Mount Holyoke College (all women) Smith College (all women) Westfield State University Williams College CONNECTICUT Large: University of Connecticut Medium: Fairfield University Quinnipiac University Yale University Small: Connecticut College Trinity College Wesleyan University NORTHERN NEW ENGLAND Large: University of New Hampshire University of Vermont Medium: Dartmouth College Middlebury College Small: Bates College Bennington College Bowdoin College Colby College College of the Atlantic Saint Anselm College -

Historical Memory Symposium | June 2-5, 2019 Gettysburg College

! Historical Memory Symposium | June 2-5, 2019 Gettysburg College | Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, USA Sunday, June 2nd 6 pm Welcome dinner at the Gettysburg Hotel Monday, June 3rd 9 am Opening Remarks & Introductions | All seminars held in Science Center 200 9:30-10:30 am Monumental Commemorations Julian Bonder, architect; Roger Williams College Exploring the role of monuments, parks and museums in preserving and celebrating historic events and in shaping collective memory 11 am-3 pm Guided Visit to Gettysburg Battlefield Led by Peter Carmichael and Jill Titus, Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College 3 pm-5:30 pm Gettysburg Museum and Visitors’ Center Tuesday, June 4th 9-10:15 am Memory vis-à-vis Recent Events in the United States and Central America Stephen Kinzer, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University Location: Science Center 200 10:30-11:45 am Historical Memory Research I: SPAIN Brief presentations by faculty and students about their research focused on historical and collective memory, with a focus on methodologies. Juanjo Romero, Resident Director, CASA Barcelona Ava Rosenberg, Returning student, CASA Spain Maria Luisa Guardiola, Professor, Swarthmore 12-1 pm Lunch 1:15-2:15 pm Historical Memory Research II: CUBA Brief presentations by faculty and students about their research focused on historical and collective memory, with a focus on methodologies. Somi Jun, Returning student, CASA Cuba Rainer Schultz, Resident Director, CASA Cuba 2:30-4 pm De-Brief and Sharing Project Ideas 5:30-7:30 pm Dinner and closing remarks | Atrium Dining Hall Speaker Bios Julian Bonder Professor of Architecture, Roger Williams University Julian Bonder is a teacher, designer and architect born in New York and raised in Argentina. -

Elite Colleges Or Colleges for the Elite?: a Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege Margaret Lee O'brien Dickinson College

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Honors Theses By Year Student Honors Theses 5-22-2011 Elite Colleges or Colleges For the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege Margaret Lee O'Brien Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_honors Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation O'Brien, Margaret Lee, "Elite Colleges or Colleges For the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege" (2011). Dickinson College Honors Theses. Paper 129. This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elite Colleges or Colleges for the Elite?: A Qualitative Analysis of Dickinson Students' Perceptions of Privilege By Margaret O'Brien Submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors Requirements For the Dickinson College Department of Sociology Professor Steinbugler, Advisor Professor Schubert, Reader Professor Love, Reader 16 May 2011 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ~----------------------~2 2. Literature Review 4 3. Methodology 20 4. Data Analysis 29 5. Conclusion 48 6. Acknowledgements 52 7. Appendix A (Interview Recruitment Flier) 53 8. Appendix B (Interview Recruitment Email) 54 9. References 55 1 Studying privileged people is important because they create the ladders that others must climb to move up in the world. Nowhere is this more true than in schools, which have been official ladders of mobility and opportunity in U.S. society for hundreds of years. Mitchell L. Stevens, Creating a Class The college experience is often portrayed as a carefree four years filled with new experiences, lifelong friendships, parties, papers and the ease of a semi-sheltered, yet independent, life. -

The Classicists of Ohio Wesleyan University: 1844-2014 © Donald Lateiner 2014

The Classicists of Ohio Wesleyan University: 1844-2014 © Donald Lateiner 2014 When Ohio Wesleyan could hire only four professors to teach in Elliott Hall (and there was yet no other building), one of the four professors taught Latin and another taught Ancient Greek. This I was told in 1979, when I arrived at Sturges Hall to teach the Classics. True or not,1 the story reflects the place of Greek and Latin in the curriculum of the mid-1800s. Our first graduate, William Godman, followed the brutally demanding “classical course.” The percentage of faculty teaching Greek and Latin steadily declined in the Nineteenth and most of the Twentieth century. New subjects and new demands attracted Wesleyan students. Currently we descry another Renaissance of antiquity at Ohio Wesleyan in Classical Studies. Sturges Hall itself was opened in 1855, its original function, as you see in the photo on the left, to serve the campus as library with alcoves divided by subject. Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams studied and revered Greek and Roman writers, their demanding languages, and their culture. Ben Franklin was not interested. For many decades, mere admission to Harvard College required a solid knowledge of Greek and Latin. One of Ohio’s sons who became President of the United States, James A. Garfield, was both a student and a teacher of Greek and Latin. Legend holds that he could write Greek with one hand, Latin with the other--at the same time. I doubt it, but Thucydides tells us humans usually doubt that others can achieve what they know they cannot. -

Opening Set for 2002 Uring the May Lumni Memorial D18 Trustee-Fac- Gymnasium Is Ulty Dinner, Alan W

Psychology_2001.qxd 5/9/03 2:13 PM Page 1 PSYCHOLOGY LAFAYETTE COLLEGE SUMMER 2001 ■ Vol.6 CHILDS WINS JAMES P. CRAWFORD AWARD Opening Set for 2002 uring the May lumni Memorial D18 trustee-fac- Gymnasium is ulty dinner, Alan W. currently being Childs, associate transformed into professor, received the Aa state-of-the-art home for James P. Crawford Lafayette’s programs in psy- Award for his out- chology and neuroscience. standing ability in The new facility will pro- classroom instruction. vide 45,000 square feet of Childs is known for his ability space on five levels including to lead classroom discussions, par- teaching laboratories, faculty ticularly in his First-Year Seminar research laboratories, shared “Human Aggression and Social faculty- student research lab- Pathology,” and his Values and oratories, and faculty offices. Science/Technology Seminar “Patient- Completion is expected to be Practitioner Interaction: The Role of sometime in 2002. Medical Technology,” noted Provost Members of the depart- June Schlueter in her remarks. ment were involved in “It was an honor to have been reviewing the plans and given an award named after some- meeting with the architects one whose career at the college I as the space was designed. have greatly admired,” says Childs. They provided advice based In a department of excellent teach- on experience in the current An architectural rendering of psychology’s new home. ers, it is a little embarrassing to be location and on exploring singled out in this way, and I think psychology facilities at other colleges. Some features include an animal of it as a compliment to the depart- research area on the lower level, common meeting spaces off the entryway ment as much as to me. -

990-PF and Its Instructions Is at /Form990pf

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491316011664 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 0- Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. By law, the 2013 IRS cannot redact the information on the form. Department of the Treasury 0- Information about Form 990-PF and its instructions is at www.irs.gov /form990pf . Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2013 , or tax year beginning 01-01-2013 , and ending 12-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 22-6029397 O/o MARGARET H EINHORN CFO&TRE Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite 6 ieiepnone number (see instructions) PO BOX 2316 Suite (609) 452-8701 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here F PRINCETON, NJ 085432316 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here F r-Final return r-Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation E If private foundation status was terminated H C heck type of organization F Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F_ Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part II, col. -

Shouse, Kay (Medal of Freedom)” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 45, folder “Shouse, Kay (Medal of Freedom)” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON May4, 1976 Nancy: I did want to talk to Mrs. Ford about the attached. I do not like to send something like this direct and would be pleased to refer it to another office if she feels that would be more appropriate. Mrs. Shouse just happens to be a most outstanding per son. PILENE CENTER/WOLr TRAP rARM PARK roR THE PERrORMING ARTS THE WOLF TRAP FOUNDATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS Mrs. Gerald R. Ford Honorary Chairman Mrs. Jouett Shouse Founder J. William Middendorf II Chairman Rodney Weir Markley, Jr. Vice-Chairman Hobart Taylor, Jr. April 20, 1976 Vice-Chairman Bradshaw Minte.1er Secretary Douglas R. Smith Mrs. Gerald R. Ford Treasurer The White House Ralph E. Becker Washington, D. C. -

Sacrifice, Curse, and the Covenant in Paul's Soteriology

SACRIFICE, CURSE, AND THE COVENANT IN PAUL'S SOTERIOLOGY Norio Yamaguchi A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/7419 This item is protected by original copyright Sacrifice, Curse, and the Covenant in Paul’s Soteriology Norio Yamaguchi This thesis is submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Sacrifice, Curse, and the Covenant in Paul’s Soteriology Presented by Norio Yamaguchi For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2015 St Mary’s College University of St Andrews - i - 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Norio Yamaguchi, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2011 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph D in July 2012; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2011 and 2015. I, Norio Yamaguchi, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language, which was provided by Sandra Peniston-Bird. Date Feb.12 2015 sig nature of candidate 2.