Green Our City Strategic Action Plan 2017-2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

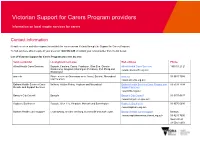

Victorian Support for Carers Program Providers

Victorian Support for Carers Program providers Information on local respite services for carers Contact information Respite services and other support is available for carers across Victoria through the Support for Carers Program. To find out more about respite in your area call 1800 514 845 or contact your local provider from the list below. List of Victorian Support for Carers Program providers by area Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Alfred Health Carer Services Bayside, Cardinia, Casey, Frankston, Glen Eira, Greater Alfred Health Carer Services 1800 51 21 21 Dandenong, Kingston, Mornington Peninsula, Port Phillip and <www.carersouth.org.au> Stonnington annecto Phone service in Grampians area: Ararat, Ballarat, Moorabool annecto 03 9687 7066 and Horsham <www.annecto.org.au> Ballarat Health Services Carer Ballarat, Golden Plains, Hepburn and Moorabool Ballarat Health Services Carer Respite and 03 5333 7104 Respite and Support Services Support Services <www.bhs.org.au> Banyule City Council Banyule Banyule City Council 03 9457-9837 <www.banyule.vic.gov.au> Baptcare Southaven Bayside, Glen Eira, Kingston, Monash and Stonnington Baptcare Southaven 03 9576 6600 <www.baptcare.org.au> Barwon Health Carer Support Colac-Otway, Greater Geelong, Queenscliff and Surf Coast Barwon Health Carer Support Barwon: <www.respitebarwonsouthwest.org.au> 03 4215 7600 South West: 03 5564 6054 Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Bass Coast Shire Council Bass Coast Bass Coast Shire Council 1300 226 278 <www.basscoast.vic.gov.au> -

CITY of MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners

CITY OF MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners The City of Melbourne respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) people of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. For the Kulin Nation, Melbourne has always been an important meeting place for events of social, educational, sporting and cultural significance. Today we are proud to say that Melbourne is a significant gathering place for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. melbourne.vic.gov.au CONTENTS Foreword 04 Context 05 Melbourne, a city that can’t stand still 05 How to thrive in a world of change 05 Our roadmap to a bold, inspirational future 05 Why creativity? Work, wandering and wellbeing 06 Case Studies 07 Düsseldorf Metro, Germany, 2016 09 Te Oro, New Zealand, 2015 11 Neighbour Doorknob Hanger 13 The Strategy 14 Appendices 16 Measuring creativity 17 How Melburnians contributed to this strategy 18 Melbourne’s Creative Strategy on a page 19 September 2018 Cover Image: SIBLING, Over Obelisk, part of Biennial Lab 2016. Photo by Bryony Jackson Image on left: Image: Circle by Naretha Williams performed at YIRRAMBOI Festival 2017. Photo Bryony Jackson Disclaimer This report is provided for information and it does not purport to be complete. While care has been taken to ensure the content in the report is accurate, we cannot guarantee is without flaw of any kind. There may be errors and omissions or it may not be wholly appropriate for your particular purposes. In addition, the publication is a snapshot in time based on historic information which is liable to change. -

Investigation Into Review of Parking Fines by the City of Melbourne

Investigation into review of parking fines by the City of Melbourne September 2020 Ordered to be published Victorian government printer Session 2018-20 P.P. No. 166 Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please call 9613 6222, using the National Relay Service on 133 677 if required, or email [email protected]. The Victorian Ombudsman pays respect to First Nations custodians of Country throughout Victoria. This respect is extended to their Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge their sovereignty was never ceded. Letter to the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly To The Honourable the President of the Legislative Council and The Honourable the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Pursuant to sections 25 and 25AA of the Ombudsman Act 1973 (Vic), I present to Parliament my Investigation into review of parking fines by the City of Melbourne. Deborah Glass OBE Ombudsman 16 September 2020 2 www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au Contents Foreword 5 What motivated Council’s approach? 56 Alleged revenue raising – the evidence 56 Background 6 Poor understanding of administrative The protected disclosure complaint 6 law principles 59 Jurisdiction 6 Inflexible policies and lack of discretion 60 Methodology 6 Culture and resistance to feedback 62 Scope 7 What motivated these decisions? 63 Procedural fairness 7 Council’s response 63 City of Melbourne 8 Conclusions 65 The Branch 9 The conduct of individuals 65 Relevant staff 10 Final comment 65 Conduct standards for Council officers 10 -

Proposed Determination of Allowances for Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors

Proposed Determination of allowances for Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors Consultation paper July 2021 1 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations and glossary ........................................................................................................ 3 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 5 2 Call for submissions ........................................................................................................... 7 3 Scope of the Determination ............................................................................................... 9 4 The Tribunal’s proposed approach ................................................................................... 10 5 Overview of roles of Councils and Council members......................................................... 11 Role and responsibilities of Mayors ..................................................................................... 13 Role and responsibilities of Deputy Mayors ........................................................................ 15 Role and responsibilities of Councillors ............................................................................... 15 Time commitment of Council role ....................................................................................... 16 Other impacts of Council role ............................................................................................. -

Application of Connectivity Modelling to Fragmented Landscapes at Local Scales

Application of connectivity modelling to fragmented landscapes at local scales Austin J. O Malley1 & Alex M. Lechner2 1 Eco Logical Australia – A Tetra Tech Company, 436 Johnston Street, Abbotsford, VIC 3067 E: [email protected] 2 School of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, 43500 Semenyih, Selangor, Malaysia E: [email protected] Multispecies connectivity modelling for conservation planning • Understanding habitat connectivity an essential requirement for effective conservation of wildlife populations • Used by planners and wildlife managers to address complex questions relating to the movement of wildlife • “What is the most effective design of a wildlife connectivity network for a particular species or suite of species”? • Important consideration in the management of road networks to avoid barriers between wildlife populations and reduce collisions • Estimating ecological connectivity at landscape scales is a complex task aided by the application of ecological models • Relatively underutilised in Australia, however, commonly used internationally in both planning and academia Connectivity Modelling and GAP CLoSR • Connectivity modelling has advanced rapidly in the last decade with improved computing power and more mainstream take-up of modelling tools in planning • Suite of modelling tools available to answer different questions (Circuitscape, Graphab, Linkage Mapper) • Recently integrated into a single decision-framework and software interface called GAP-CloSR1 • -

Victoria Harbour Docklands Conservation Management

VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Places Victoria & City of Melbourne June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi PROJECT TEAM xii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and brief 1 1.2 Melbourne Docklands 1 1.3 Master planning & development 2 1.4 Heritage status 2 1.5 Location 2 1.6 Methodology 2 1.7 Report content 4 1.7.1 Management and development 4 1.7.2 Background and contextual history 4 1.7.3 Physical survey and analysis 4 1.7.4 Heritage significance 4 1.7.5 Conservation policy and strategy 5 1.8 Sources 5 1.9 Historic images and documents 5 2.0 MANAGEMENT 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Management responsibilities 7 2.2.1 Management history 7 2.2.2 Current management arrangements 7 2.3 Heritage controls 10 2.3.1 Victorian Heritage Register 10 2.3.2 Victorian Heritage Inventory 10 2.3.3 Melbourne Planning Scheme 12 2.3.4 National Trust of Australia (Victoria) 12 2.4 Heritage approvals & statutory obligations 12 2.4.1 Where permits are required 12 2.4.2 Permit exemptions and minor works 12 2.4.3 Heritage Victoria permit process and requirements 13 2.4.4 Heritage impacts 14 2.4.5 Project planning and timing 14 2.4.6 Appeals 15 LOVELL CHEN i 3.0 HISTORY 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Pre-contact history 17 3.3 Early European occupation 17 3.4 Early Melbourne shipping and port activity 18 3.5 Railways development and expansion 20 3.6 Victoria Dock 21 3.6.1 Planning the dock 21 3.6.2 Constructing the dock 22 3.6.3 West Melbourne Dock opens -

VICTORIA Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne Royal

VICTORIA Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne Royal WHERE SHOULD ALL THE TREES GO? STATE BY STATE VIC WHAT’S HAPPENING? There has been an In VIC, 44% of urban LGAs have overall increase of undergone a significant loss of tree canopy, Average canopy cover for urban VIC is 3% in hard with only 8% having had a significant surfaces, which is increase in shrubbery. 18.83% exactly the same down 2.06% from rate of increase as NSW, but overall 20.89% VIC has around in 2013. 5% less hard surfaces than NSW. THERE HAVE BEEN QUITE A FEW SIGNIFICANT CANOPY LOSSES. – Notably in the City of Ballarat (5%), Banyule City Council (4.6%), Cardinia Shire Council (5.9%), Nillumbik Shire Council (12.8%), Maroondah City Council (4.7%), Mornington Peninsula Shire (4.7%) and Eira City Council (4.8%). WHERE SHOULD ALL THE TREES GO? VICTORIA VIC THE MOST & LEAST VULNERABLE 2.5 Rating Glen Eira City Council, Kingston City 3.0 Rating Council, City of Stonnington 2.0 Rating City of Port Phillip, Maroondah City Council, Moonee Valley City Council, Whittlesea City of Casey, Banyule City Council Council, Wyndham City Council 3.5 Rating 1.5 Rating City of Boroondara, City of Monash, Mornington Peninsula Shire, Frankston City Council, City of Greater Bendigo, City of Greater Dandenong, Cardinia Shire Council, City of Melbourne City of Greater Geelong, Hobsons Bay City Council, City of Melton 1.0 Rating 4.0 Rating City of Brimbank, Maribyrnong City Council, Yarra City Council, City of Whitehorse, Manningham City Council Moreland City Council 4.5 Rating Yarra Ranges Council, -

Spring 2020 Ear Nd Y 42

Spring 2020 ear nd y 42 ISSUE 190 THE NORTH & WEST MELBOURNE NEWS IS PRODUCED BY VOLUNTEERS AT THE CENTRE: Connecting Community in North & West Melbourne Inc www.centre.org.au A stitch in Pandemic affects time behind the mask policing in the crusader inner suburbs Anna Huynh Nicole Pereira masks. “If they can’t pay the fine, eana Eddington began stitching it generally becomes a debt,” he says. Dgowns to protect front-line A policeman’s lot is not a happy Craig is keenly aware that healthcare workers during the first one (Pirates of Penzance) homelessness isn’t easily solved. lockdown. “It’s a long-term project for housing In the harsher stage-four lockdown, ergeant Craig McIntosh can services. But most of our local the new North Melbourne resident Sgive the lie to that old line. A homeless are reasonably easy to talk found another way to help her policeman for 14 years and now to, and we run several operations community. She turned her sewing based at Melbourne West Police and support programs that involve skills to making masks, and her Station, he loves his work. “I dreaded chatting with them,” he says. efforts have seen her turn out well a desk job and I didn’t want to be He is heartened that recent COVID- over 700. doing the same things day in and related offences are generally milder It all started in her own apartment day out,” he says. than the occasional mayhem of complex. Deana was taking a craft At Melbourne West, Craig’s beat Friday and Saturday nights. -

Making the City of Melbourne More Inclusive for People with Disability

Making the City of Melbourne more inclusive for people with disability Jerome N Rachele, Ilan Wiesel, Ellen van Holstein, Tessa de Vries, Celia Green, Ellen Bicknell May 2019 Research Team Dr Jerome Rachele, Co-Lead Investigator, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne, and NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health Dr Ilan Wiesel, Co-Investigator, School of Geography, University of Melbourne Dr Ellen van Holstein, Co-Investigator, School of Geography, University of Melbourne Ms Tessa de Vries, Project advisor, Melbourne Disability Institute, University of Melbourne Ms Celia Green, Workshop Lead, Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health, University of Melbourne, UNSW, Canberra Ms Ellen Bicknell, Research Assistant, Centre for Health Equity, University of Melbourne Acknowledgements Funding The research is co-funded by the City of Melbourne, Melbourne Disability Institute, and Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, and Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation Additional Support The research team acknowledges the support provided by the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health. City of Melbourne Partners Ms Vickie Feretopoulos, Co-Lead Investigator, City of Melbourne Ms Georgie Myer, Team Leader Community Engagement and Partnerships and Acting Manager, Placemaking and Engagement, City of Melbourne Mr Peter Whelan, Metro Access, City of Melbourne Stakeholder Groups The following organisations provided advice and support recruiting participants for the stakeholder workshops conducted in February 2019: • City of Melbourne Disability Advisory • Brain Injury Matters We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the Committee • Association of Children with Disability land on which we work, and pay our respects to • City of Melbourne Inclusive • Victorian Advocacy League for the Elders, past and present. -

Transport Strategy 2030 Contents

TRANSPORT STRATEGY 2030 CONTENTS Foreword 3 Implementation 106 Executive Summary 4 Policy summary 108 Vision 2030 8 Implementation plan 110 Context 20 Walking and Station Precincts map 112 Context map 22 Public Transport map 114 Policy alignment 25 Bikes map 116 Challenges and opportunities 26 Motor Vehicles map 118 Strategy development 28 2030 Proposed Integrated Network map 120 Theme 1: A Safe and Liveable City 30 Appendices 122 Challenges and opportunities 32 References 122 Outcomes 1-4 34 Glossary 123 Theme 2: An Efficient and Productive City 60 Evidence-based public transport planning 126 Challenges and opportunities 62 Outcomes 5-9 64 Theme 3: A Dynamic and Adaptable City 88 Challenges and opportunities 90 A CONNECTED CITY Outcomes 10-13 92 In a connected city, all people and goods can move to, from and within the city efficiently. Catering for growth and safeguarding prosperity will require planning for an efficient and sustainable transport network. Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners Disclaimer The City of Melbourne respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners This report is provided for information and it does not purport to be complete. While care has been taken to ensure the content in the report is accurate, we cannot guarantee it is without flaw of any kind. There may be errors and omissions or it may not be wholly appropriate for your particular purposes. In addition, the publication of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) people is a snapshot in time based on historic information which is liable to change. The City of Melbourne accepts no responsibility and disclaims all liability for any error, loss or of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. -

Council Looks Set to Support Overshadowing

FOR THE MONTH OF SEPTEMBER, 2014 ISSUE 02 FREE WWW.CBDNEWS.COM.AU Food Events Nightlife LUNCH TIME 14 AFTER WORK 15 THE WEEKEND 17 HELP FOR GRESTE CHURCH DEFIES TREND ANAÏS’S ACHIEVEMENT RETAIL BOOM page 3 page 9 page 5 page 23 Council looks set to support overshadowing By Shane Scanlan Cbus is entitled to build a lower structure on just about all the site but prefers to leave at least a third of it as public open space. It return, it wants to build a 300m tower on Th e City of Melbourne the remaining area. Strictly-speaking, Cbus appears ready to support doesn’t need the council’s approval for the amendment to planning law it is seeking over-shadowing of the south and the decision remains with the Planning bank of the Yarra in return for Minister, Matthew Guy. Cbus CEO Adrian desperately-needed open space Pozzo did not respond to CBD News. Monash Uni student Hannah Scholte wants to speak with CBD residents. in the CBD. At the Future Melbourne Committee meeting of August 12, most councillors Hannah wants your story spoke glowingly of the proposal, however Th e council has not previously supported they voted for a month’s deferral to allow over-shadowing of the river and the principle closer collaboration with Cbus. Honours year journalism student Hannah Scholte wants to know has remained “sacrosanct”. Ironically, until recently, Melburnians have what it is like to live in the CBD. Lord Mayor Robert Doyle used the term enjoyed a vast open plaza along the length “sacrosanct” on August 5 when making of Collins St in front of the old Suncorp Th e Monash University student is making a “I get the feeling that now is a really crucial an impassioned plea to Planning Minister building since 1965. -

City of Melton’S

Shaping a city A whole of Government approach to the City of Melton’s population boom 2020—2021 Federal Government Budget Submission Pauline Hobbs | Advocacy Officer P |03 9747 5440 E | [email protected] W | melton.vic.gov.au 2 | P a g e INTRODUCTION The City of Melton is one of Australia’s fastest growing municipalities; growth that represents not only exciting opportunities, but also significant, immediate and emerging challenges. Melton City Council is calling on all levels of government to partner to deliver essential infrastructure and services as we shape an emerging city to increase liveability. KEY PRIORITIES This document outlines Melton City Council’s Federal budget submission for the municipality, with a view to having these priorities included in the Federal Government’s 2020/2021 Budget: HEALTH PRECINCT Contribute funding to build the new Melton Hospital or fund a Page specialist centre within the hospital 10 PUBLIC TRANSPORT: Co-fund the Western Rail Plan with the Victorian State Page RAIL Government to deliver an efficient and frequent train system with 11 new stations for residents to access employment, education and health services FREIGHT Commit to co-fund the Western Interstate Freight Terminal Page (WIFT) as part of the Commonwealth Inland Rail Project to 12 increase productivity and reduce congestion WESTERN HIGHWAY Use the committed $50 million congestion fund toward the Page development of a business case and upgrade the critical arterial 13 road link A TERTIARY Deliver TAFE and tertiary education in the City of Melton Page EXPERIENCE 14 EARLY YEARS Ongoing universal access funding for four-year-old kinder Page EDUCATION 15 SPORTS & Build critical sport and recreational infrastructure including the Page RECREATION Macpherson Regional Park (Stage 2) redevelopment.