Victorian Historical Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Support for Carers Program Providers

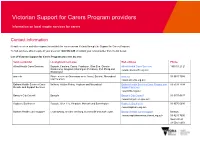

Victorian Support for Carers Program providers Information on local respite services for carers Contact information Respite services and other support is available for carers across Victoria through the Support for Carers Program. To find out more about respite in your area call 1800 514 845 or contact your local provider from the list below. List of Victorian Support for Carers Program providers by area Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Alfred Health Carer Services Bayside, Cardinia, Casey, Frankston, Glen Eira, Greater Alfred Health Carer Services 1800 51 21 21 Dandenong, Kingston, Mornington Peninsula, Port Phillip and <www.carersouth.org.au> Stonnington annecto Phone service in Grampians area: Ararat, Ballarat, Moorabool annecto 03 9687 7066 and Horsham <www.annecto.org.au> Ballarat Health Services Carer Ballarat, Golden Plains, Hepburn and Moorabool Ballarat Health Services Carer Respite and 03 5333 7104 Respite and Support Services Support Services <www.bhs.org.au> Banyule City Council Banyule Banyule City Council 03 9457-9837 <www.banyule.vic.gov.au> Baptcare Southaven Bayside, Glen Eira, Kingston, Monash and Stonnington Baptcare Southaven 03 9576 6600 <www.baptcare.org.au> Barwon Health Carer Support Colac-Otway, Greater Geelong, Queenscliff and Surf Coast Barwon Health Carer Support Barwon: <www.respitebarwonsouthwest.org.au> 03 4215 7600 South West: 03 5564 6054 Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Bass Coast Shire Council Bass Coast Bass Coast Shire Council 1300 226 278 <www.basscoast.vic.gov.au> -

CITY of MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners

CITY OF MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners The City of Melbourne respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) people of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. For the Kulin Nation, Melbourne has always been an important meeting place for events of social, educational, sporting and cultural significance. Today we are proud to say that Melbourne is a significant gathering place for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. melbourne.vic.gov.au CONTENTS Foreword 04 Context 05 Melbourne, a city that can’t stand still 05 How to thrive in a world of change 05 Our roadmap to a bold, inspirational future 05 Why creativity? Work, wandering and wellbeing 06 Case Studies 07 Düsseldorf Metro, Germany, 2016 09 Te Oro, New Zealand, 2015 11 Neighbour Doorknob Hanger 13 The Strategy 14 Appendices 16 Measuring creativity 17 How Melburnians contributed to this strategy 18 Melbourne’s Creative Strategy on a page 19 September 2018 Cover Image: SIBLING, Over Obelisk, part of Biennial Lab 2016. Photo by Bryony Jackson Image on left: Image: Circle by Naretha Williams performed at YIRRAMBOI Festival 2017. Photo Bryony Jackson Disclaimer This report is provided for information and it does not purport to be complete. While care has been taken to ensure the content in the report is accurate, we cannot guarantee is without flaw of any kind. There may be errors and omissions or it may not be wholly appropriate for your particular purposes. In addition, the publication is a snapshot in time based on historic information which is liable to change. -

City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 Early Childhood Community Profile

Early Childhood Community Profile City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 Early Childhood Community Profile City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 This Aboriginal Early childhood community profile was prepared by the Office for Children and Portfolio CdiiCoordination, ini the h ViVictorian i Government G DDepartment of f EdEducation i and d EEarly l ChildhChildhood d DDevelopment. l The series of Early Childhood community profiles draw on data on outcomes for children compiled through the Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System (VCAMS). The profiles are intended to provide local level information on the health, wellbeing, learning, safety and developmental outcomes of young Aboriginal children. They are published to aid Aboriginal organisations and local councils, as well as Best Start partnerships, with local service development, innovation and program planning to improve these outcomes. The Department of Human Services, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and the Australian Bureau of Statistics provided data for this document. Aboriginal Early Childhood Community Profile i Published by the Victorian Government DepartmentDepartment of Education and Early Childhood Development, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. January 2010 © Copyright State of Victoria, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisionsprovisions of the Copyright Act 19681968.. Principal author and analyst: Hiba -

Climate Adaptation Strategy 2021–2025 DRAFT for PUBLIC COMMENT Who Is This Document For?

DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT Grampians Region Climate Adaptation Strategy 2021–2025 DRAFT FOR PUBLIC COMMENT Who is this document for? Victoria’s Climate Change Act requires the Government to ‘take strong action to build resilience to, and reduce the risks posed by, climate change and protect those most vulnerable.’11 Development of this community-led Grampians Region Climate Adaptation Strategy and coordination of its implementation has been funded by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP). The Strategy was written collaboratively by members of Regional Climate Adaptation Groups (RCAG) representing state government, agencies, local government, universities, farmers, business and community in close consultation with key stakeholders throughout the Grampians Region. It is intended that everyone involved can see their own climate adaptation aspirations reflected. Efforts across the Region can be better coordinated, leading to improved outcomes for communities and the environment. Community groups, local governments, agencies and organisations can use this document to: • Align their own climate adaptation planning and projects to regional goals and outcomes, providing opportunities for partnerships and collaboration to maximise collective impact. • Apply for grants funded by DELWP. • Support funding applications for other government, corporate and philanthropic grants. Activities aligned with these goals and outcomes will be able to demonstrate a high level of strategic thinking at a regional level, stakeholder engagement -

2009-10 Annual Report on Drinking Water Quality in Victoria

Annual report on drinking water quality in Victoria 2009–2010 Annual report on drinking water quality in Victoria 2009–2010 Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, please telephone 1300 761 874, use the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required or email [email protected] This document is also available in PDF format on the internet at: www.health.vic.gov.au/environment/water/drinking Published by the Victorian Government, Department of Health, Melbourne, Victoria ISBN 978 0 7311 6340 3 © Copyright, State of Victoria, Department of Health, 2011 This publication is copyright, no part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the State Government of Victoria, 50 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. Printed on sustainable paper by Impact Digital, Unit 3-4, 306 Albert St, Brunswick 3056 March 2011 (1101024) Foreword The provision of safe drinking water to Victoria’s urban and rural communities is essential for maintaining public health and wellbeing. In Victoria, drinking water quality is protected by legislation that recognises drinking water’s importance to the state’s ongoing social and economic wellbeing. The regulatory framework for Victoria’s drinking water is detailed in the Safe Drinking Water Act 2003 and the Safe Drinking Water Regulations 2005. The Act and Regulations provide a comprehensive framework based on a catchment-to-tap approach that actively safeguards the quality of drinking water throughout Victoria. The main objectives of this regulatory framework are to ensure that: • where water is supplied as drinking water, it is safe to drink • any water not intended to be drinking water cannot be mistaken for drinking water • water quality information is disclosed to consumers and open to public accountability. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 87, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2016 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history produced twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Jill Barnard Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) Marie Clark Mimi Colligan Don Garden (President, RHSV) Don Gibb David Harris (Editor, Victorian Historical Journal) Kate Prinsley Marian Quartly (Editor, History News) John Rickard Judith Smart (Review Editor) Chips Sowerwine Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 286 VOLUME 87, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2016 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2016 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

A Grampians Massacre? an Analysis of the Participant’S Account of an Early Whyte Brothers Massacre in the Portland District

A Grampians Massacre? An analysis of the Participant’s account of an early Whyte Brothers massacre in the Portland district by PD Gardner (written with assistance from the Search Foundation.This is an unpublished essay completed about 2010) The account of this massacre - which I consider a primary source and not as well known as it should be - went as follows: “ ‘Why' said one of them, the elder of the two, ‘I can remember when they used to shoot down the blacks in this colony as you would do kangaroos, all because they sometimes killed a few sheep. I remember down in the Port District, when the four Parks and three other men, I was one of them, shot sixty-nine in one afternoon. The devils had stolen about 100 sheep and driven them away to the ranges. When they got them there they broke their legs to prevent them escaping, and were killing them and eating them at their leisure ... We all mounted horses, and armed with rifles set off in hot pursuit. It was early morning when we started, and about the middle of the day we came up with the black rascals, and a rare chase we had of it. They set off like mad, about one hundred and fifty of them, never showing fight in the least. The ranges were so rocky that we had to dismount and follow them on foot, and after two or three hours chase we got them beautiful - right between a crossfire, a steep rock on one side they could not climb, and rifles on each of the other. -

Middle Island Little Penguin Monitoring Program 2015-16 Season Report

Middle Island Little Penguin Monitoring Program 2015-16 Season Report By Jess Bourchier & Lauren Kivisalu 2016 Project Partners: Middle Island Little Penguin Monitoring 2015-16 Season Report Citation Bourchier J. and L. Kivisalu (2016) Middle Island Little Penguin Monitoring Program 2015-16 Season Report. Report to Warrnambool Coastcare Landcare Group. NGT Consulting – Nature Glenelg Trust, Mount Gambier, South Australia. Correspondence in relation to this report contact Ms Jess Bourchier Project Ecologist NGT Consulting (08) 8797 8596 [email protected] Cover photos (left to right): Volunteers crossing to Middle Island (J Bourchier), Maremma Guardian Dog on Middle Island (M Wells), Sunset from Middle Island (J Bourchier), 2-3 week old Little Penguin chick (J Bourchier), 7 week old Little Penguin chick (J Bourchier) Disclaimer This report was commissioned by Warrnambool Coastcare Landcare. Although all efforts were made to ensure quality, it was based on the best information available at the time and no warranty express or implied is provided for any errors or omissions, nor in the event of its use for any other purposes or by any other parties. Page ii of 22 Middle Island Little Penguin Monitoring 2015-16 Season Report Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge and thank the following people and funding bodies for their assistance during the monitoring program: • Warrnambool Coastcare Landcare Network (WCLN), in particular Louise Arthur, Little Penguin Officer. • Little Penguin Monitoring Program volunteers, with particular thanks to Louise Arthur Melanie Wells, John Sutherlands and Vince Haberfield. • Middle Island Project Working Group, which includes representatives from WCLN, Warrnambool City Council, Deakin University, Department of Environment, Land Water and Planning (DELWP). -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 89, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2018 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history produced twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Judith Smart and Richard Broome (Editors, Victorian Historical Journal) Jill Barnard Rozzi Bazzani Sharon Betridge (Co-editor, History News) Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) (Co-Editor, History News) Marie Clark Jonathan Craig (Review Editor) Don Garden (President, RHSV) John Rickard Judith Smart Lee Sulkowska Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 290 VOLUME 89, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2018 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2018 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

7.5. Final Outcomes of 2020 General Valuation

Council Meeting Agenda 24/08/2020 7.5 Final outcomes of 2020 General Valuation Abstract This report provides detailed information in relation to the 2020 general valuation of all rateable property and recommends a Council resolution to receive the 1 January 2020 General Valuation in accordance with section 7AF of the Valuation of Land Act 1960. The overall movement in property valuations is as follows: Site Value Capital Improved Net Annual Value Value 2019 Valuations $82,606,592,900 $112,931,834,000 $5,713,810,200 2020 Valuations $86,992,773,300 $116,769,664,000 $5,904,236,100 Change $4,386,180,400 $3,837,830,000 $190,425,800 % Difference 5.31% 3.40% 3.33% The level of value date is 1 January 2020 and the new valuation came into effect from 1 July 2020 and is being used for apportioning rates for the 2020/21 financial year. The general valuation impacts the distribution of rating liability across the municipality. It does not provide Council with any additional revenue. The distribution of rates is affected each general valuation by the movement in the various property classes. The important point from an equity consideration is that all properties must be valued at a common date (i.e. 1 January 2020), so that all are affected by the same market. Large shifts in an individual property’s rate liability only occurs when there are large movements either in the value of a property category (e.g. residential, office, shops, industrial) or the value of certain locations, which are outside the general movements in value across all categories or locations. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

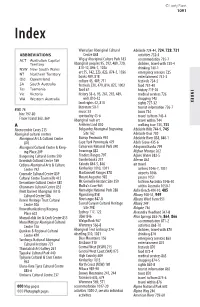

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre