Brimbank City Council1.91 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Support for Carers Program Providers

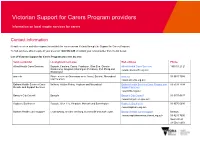

Victorian Support for Carers Program providers Information on local respite services for carers Contact information Respite services and other support is available for carers across Victoria through the Support for Carers Program. To find out more about respite in your area call 1800 514 845 or contact your local provider from the list below. List of Victorian Support for Carers Program providers by area Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Alfred Health Carer Services Bayside, Cardinia, Casey, Frankston, Glen Eira, Greater Alfred Health Carer Services 1800 51 21 21 Dandenong, Kingston, Mornington Peninsula, Port Phillip and <www.carersouth.org.au> Stonnington annecto Phone service in Grampians area: Ararat, Ballarat, Moorabool annecto 03 9687 7066 and Horsham <www.annecto.org.au> Ballarat Health Services Carer Ballarat, Golden Plains, Hepburn and Moorabool Ballarat Health Services Carer Respite and 03 5333 7104 Respite and Support Services Support Services <www.bhs.org.au> Banyule City Council Banyule Banyule City Council 03 9457-9837 <www.banyule.vic.gov.au> Baptcare Southaven Bayside, Glen Eira, Kingston, Monash and Stonnington Baptcare Southaven 03 9576 6600 <www.baptcare.org.au> Barwon Health Carer Support Colac-Otway, Greater Geelong, Queenscliff and Surf Coast Barwon Health Carer Support Barwon: <www.respitebarwonsouthwest.org.au> 03 4215 7600 South West: 03 5564 6054 Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Bass Coast Shire Council Bass Coast Bass Coast Shire Council 1300 226 278 <www.basscoast.vic.gov.au> -

CITY of MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners

CITY OF MELBOURNE CREATIVE STRATEGY 2018–2028 Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners The City of Melbourne respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) people of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. For the Kulin Nation, Melbourne has always been an important meeting place for events of social, educational, sporting and cultural significance. Today we are proud to say that Melbourne is a significant gathering place for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. melbourne.vic.gov.au CONTENTS Foreword 04 Context 05 Melbourne, a city that can’t stand still 05 How to thrive in a world of change 05 Our roadmap to a bold, inspirational future 05 Why creativity? Work, wandering and wellbeing 06 Case Studies 07 Düsseldorf Metro, Germany, 2016 09 Te Oro, New Zealand, 2015 11 Neighbour Doorknob Hanger 13 The Strategy 14 Appendices 16 Measuring creativity 17 How Melburnians contributed to this strategy 18 Melbourne’s Creative Strategy on a page 19 September 2018 Cover Image: SIBLING, Over Obelisk, part of Biennial Lab 2016. Photo by Bryony Jackson Image on left: Image: Circle by Naretha Williams performed at YIRRAMBOI Festival 2017. Photo Bryony Jackson Disclaimer This report is provided for information and it does not purport to be complete. While care has been taken to ensure the content in the report is accurate, we cannot guarantee is without flaw of any kind. There may be errors and omissions or it may not be wholly appropriate for your particular purposes. In addition, the publication is a snapshot in time based on historic information which is liable to change. -

Investigation Into Review of Parking Fines by the City of Melbourne

Investigation into review of parking fines by the City of Melbourne September 2020 Ordered to be published Victorian government printer Session 2018-20 P.P. No. 166 Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please call 9613 6222, using the National Relay Service on 133 677 if required, or email [email protected]. The Victorian Ombudsman pays respect to First Nations custodians of Country throughout Victoria. This respect is extended to their Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge their sovereignty was never ceded. Letter to the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly To The Honourable the President of the Legislative Council and The Honourable the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly Pursuant to sections 25 and 25AA of the Ombudsman Act 1973 (Vic), I present to Parliament my Investigation into review of parking fines by the City of Melbourne. Deborah Glass OBE Ombudsman 16 September 2020 2 www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au Contents Foreword 5 What motivated Council’s approach? 56 Alleged revenue raising – the evidence 56 Background 6 Poor understanding of administrative The protected disclosure complaint 6 law principles 59 Jurisdiction 6 Inflexible policies and lack of discretion 60 Methodology 6 Culture and resistance to feedback 62 Scope 7 What motivated these decisions? 63 Procedural fairness 7 Council’s response 63 City of Melbourne 8 Conclusions 65 The Branch 9 The conduct of individuals 65 Relevant staff 10 Final comment 65 Conduct standards for Council officers 10 -

Proposed Determination of Allowances for Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors

Proposed Determination of allowances for Mayors, Deputy Mayors and Councillors Consultation paper July 2021 1 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations and glossary ........................................................................................................ 3 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 5 2 Call for submissions ........................................................................................................... 7 3 Scope of the Determination ............................................................................................... 9 4 The Tribunal’s proposed approach ................................................................................... 10 5 Overview of roles of Councils and Council members......................................................... 11 Role and responsibilities of Mayors ..................................................................................... 13 Role and responsibilities of Deputy Mayors ........................................................................ 15 Role and responsibilities of Councillors ............................................................................... 15 Time commitment of Council role ....................................................................................... 16 Other impacts of Council role ............................................................................................. -

Our Asset Management Journey

Our Asset Management Journey Professor Sujeeva Setunge Deputy Dean, Research and Innovation School of Engineering 1 RMIT Journey in Infrastructure Asset Management • Central Asset Management System (CAMS) for Buildings • CAMS-Drainage • Disaster resilience of bridges, culverts and floodways • CAMS-Bridges • Automated Tree inventory using airborne LiDar and Aerial imagery • Intelligent Asset Management in Community Partnership – A smart cities project • Future cities CRC – New!! 2 CAMS for Buildings CAMS Mobile • Australian Research council grant in partnership with – MAV – City of Glen Eira – City of Kingston – City of greater Dandenong – Mornington Peninsula shire – City of Monash – City of Brimbank • State government grant to develop the cloud hosted platform • City of Melbourne investment to develop practical features such as backlog, scenario analysis, risk profile • RMIT University property services and City of Melbourne – CAMS Mobile inspection app 3 CAMS for Buildings - Features 1. Database management 2. Data exploration 3. Deterioration prediction 4. Budget calculation 5. Backlog estimation 6. Risk management 4 4 RMIT University©2015 CAMS clients Property Services Australia | Vietnam 5 CAMS TECHNOLOGY - Buildings Current Capability Research In Progress Next stage Data Driven Models for Multi-objective . Cross assets CAMS 700 components Decision Making . Augmented Cost and other input Life-Cycle Physical degradation Reality Scenarios Analysis Modelling modelling – improve . Emergency Risk-cost Relationship accuracy manageme -

Application of Connectivity Modelling to Fragmented Landscapes at Local Scales

Application of connectivity modelling to fragmented landscapes at local scales Austin J. O Malley1 & Alex M. Lechner2 1 Eco Logical Australia – A Tetra Tech Company, 436 Johnston Street, Abbotsford, VIC 3067 E: [email protected] 2 School of Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, 43500 Semenyih, Selangor, Malaysia E: [email protected] Multispecies connectivity modelling for conservation planning • Understanding habitat connectivity an essential requirement for effective conservation of wildlife populations • Used by planners and wildlife managers to address complex questions relating to the movement of wildlife • “What is the most effective design of a wildlife connectivity network for a particular species or suite of species”? • Important consideration in the management of road networks to avoid barriers between wildlife populations and reduce collisions • Estimating ecological connectivity at landscape scales is a complex task aided by the application of ecological models • Relatively underutilised in Australia, however, commonly used internationally in both planning and academia Connectivity Modelling and GAP CLoSR • Connectivity modelling has advanced rapidly in the last decade with improved computing power and more mainstream take-up of modelling tools in planning • Suite of modelling tools available to answer different questions (Circuitscape, Graphab, Linkage Mapper) • Recently integrated into a single decision-framework and software interface called GAP-CloSR1 • -

Victoria Harbour Docklands Conservation Management

VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Places Victoria & City of Melbourne June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi PROJECT TEAM xii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and brief 1 1.2 Melbourne Docklands 1 1.3 Master planning & development 2 1.4 Heritage status 2 1.5 Location 2 1.6 Methodology 2 1.7 Report content 4 1.7.1 Management and development 4 1.7.2 Background and contextual history 4 1.7.3 Physical survey and analysis 4 1.7.4 Heritage significance 4 1.7.5 Conservation policy and strategy 5 1.8 Sources 5 1.9 Historic images and documents 5 2.0 MANAGEMENT 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Management responsibilities 7 2.2.1 Management history 7 2.2.2 Current management arrangements 7 2.3 Heritage controls 10 2.3.1 Victorian Heritage Register 10 2.3.2 Victorian Heritage Inventory 10 2.3.3 Melbourne Planning Scheme 12 2.3.4 National Trust of Australia (Victoria) 12 2.4 Heritage approvals & statutory obligations 12 2.4.1 Where permits are required 12 2.4.2 Permit exemptions and minor works 12 2.4.3 Heritage Victoria permit process and requirements 13 2.4.4 Heritage impacts 14 2.4.5 Project planning and timing 14 2.4.6 Appeals 15 LOVELL CHEN i 3.0 HISTORY 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Pre-contact history 17 3.3 Early European occupation 17 3.4 Early Melbourne shipping and port activity 18 3.5 Railways development and expansion 20 3.6 Victoria Dock 21 3.6.1 Planning the dock 21 3.6.2 Constructing the dock 22 3.6.3 West Melbourne Dock opens -

Food Safety in Focus Food Act Report 2010 Food Safety in Focus Food Act Report 2010 This Report Has Been Developed As Required Under the Food Act 1984 (S

Food safety in focus Food Act report 2010 Food safety in focus Food Act report 2010 This report has been developed as required under the Food Act 1984 (s. 7(C)). If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format please phone 1300 364 352 using the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email: [email protected] This document is available as a PDF on the internet at: www.health.vic.gov.au/foodsafety © Copyright, State of Victoria, Department of Health 2012 This publication is copyright, no part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 50 Lonsdale St, Melbourne. Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual services, facilities or recipients of services. March 2012 (1201039) Print managed by Finsbury Green. Printed on sustainable paper. ISSN 2200-1220 (Print) ISSN 2200-1239 (Online) Food safety in focus Food Act report 2010 Contents From the Minister for Health 1 From the Municipal Association of Victoria 2 Highlights for 2010 3 About this report 6 Food safety reform in Victoria 7 Food regulation: a shared responsibility 15 Keeping food-borne illness in check 19 Safer food, better business: Victoria’s food industry 23 Annual review 2010 27 Supporting food safety statewide 43 Workforce: the capacity to change 49 In your municipality 55 The national picture 93 Looking forward 97 Appendices 99 -

The Brimbank Housing Strategy

HOME AND HOUSED The Brimbank Housing Strategy August 2012 OVERVIEW Our Vision Th e Brimbank Housing Strategy, ‘Home and Housed’, has been developed by talking to the community, as well as conducting research and analysis Our vision for housing in the City of Brimbank is: since late 2010. • A place to live - accommodating growth by determining the location Th e main challenges the ‘Home and Housed’ strategy seeks to address are: of new housing in Brimbank. • Population growth. • A home for everybody - meeting the housing needs of diff erent people in the Brimbank community. • An ageing population. • Liveable neighbourhoods - protecting Brimbank’s existing suburbs • Housing aff ordability, both for homes to buy and to rent. and ensuring supporting infrastructure, including green open space, • More choice in housing. is provided. • Keeping the suburban character of Brimbank that residents enjoy. Th e population of Brimbank is growing and housing needs are changing. Th e municipality adjoins the Melton and Wyndham growth areas - which • Th e provision of roads, drainage, sewerage, green open spaces, together form the fastest growing region in Australia. As metropolitan transport etc., sometimes referred to as ‘infrastructure capacity’, in Melbourne re-orientates to the west, the pressure for residential conjunction with residential development. development in Brimbank will continue. Th e Brimbank Housing Strategy • Development of local residential design guidelines to preserve local is about responding to this growth and putting in place a plan that will character. determine where new housing is best located so that the existing character of Brimbank’s suburbs is protected. Th e Brimbank Housing Strategy, ‘Home and Housed’, is Council’s ten year plan to manage future housing growth so that it best meets the needs of the community into the future. -

VICTORIA Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne Royal

VICTORIA Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne Royal WHERE SHOULD ALL THE TREES GO? STATE BY STATE VIC WHAT’S HAPPENING? There has been an In VIC, 44% of urban LGAs have overall increase of undergone a significant loss of tree canopy, Average canopy cover for urban VIC is 3% in hard with only 8% having had a significant surfaces, which is increase in shrubbery. 18.83% exactly the same down 2.06% from rate of increase as NSW, but overall 20.89% VIC has around in 2013. 5% less hard surfaces than NSW. THERE HAVE BEEN QUITE A FEW SIGNIFICANT CANOPY LOSSES. – Notably in the City of Ballarat (5%), Banyule City Council (4.6%), Cardinia Shire Council (5.9%), Nillumbik Shire Council (12.8%), Maroondah City Council (4.7%), Mornington Peninsula Shire (4.7%) and Eira City Council (4.8%). WHERE SHOULD ALL THE TREES GO? VICTORIA VIC THE MOST & LEAST VULNERABLE 2.5 Rating Glen Eira City Council, Kingston City 3.0 Rating Council, City of Stonnington 2.0 Rating City of Port Phillip, Maroondah City Council, Moonee Valley City Council, Whittlesea City of Casey, Banyule City Council Council, Wyndham City Council 3.5 Rating 1.5 Rating City of Boroondara, City of Monash, Mornington Peninsula Shire, Frankston City Council, City of Greater Bendigo, City of Greater Dandenong, Cardinia Shire Council, City of Melbourne City of Greater Geelong, Hobsons Bay City Council, City of Melton 1.0 Rating 4.0 Rating City of Brimbank, Maribyrnong City Council, Yarra City Council, City of Whitehorse, Manningham City Council Moreland City Council 4.5 Rating Yarra Ranges Council, -

Daring to Be Great. Economic Development and Jobs Strategy for the Sunshine Gateway Precinct

SUNSHINE DARING TO BE GREAT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND JOBS STRATEGY FOR THE SUNSHINE GATEWAY PRECINCT WoMEDA WEST OF MELBOURNE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ALLIANCE, 2019 WOMEDA I 1 Acknowledgement of Country CONTENTS We acknowledge the Ancestors, Elders and families of the Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) of the Kulin who are the traditional owners of the land. As we share our own knowledge practices, MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 4 may we pay respect to the deep knowledge embedded within the Aboriginal community and their ownership of Country. A SUNSHINE – DARING TO BE GREAT 7 The Wurundjeri people were the custodians of the land in the Port Phillip Bay region, including the City of Brimbank, B SUNSHINE 2036 9 for over 40,000 years before European settlement. Brimbank lies within the area occupied by the C WHAT DOES SUCCESS LOOK LIKE? 10 Kurung-Jang-Balluk and Marin-Balluk clans of the Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) who form part of D WHAT IS NEEDED FOR SUNSHINE TO SUCCEED? 12 the larger Kulin Nation. Other groups who occupied land in the area include the Yalukit- E SUNSHINE GATEWAY: THE BIG PICTURE 14 Willam and Marpeang-Bulluk clans. We acknowledge that the land on F SUNSHINE TRIANGLE - UP CLOSE 16 which we meet is a place of age old ceremonies of celebration, initiation G JOBS ARE CRITICAL 18 and renewal and that the Kulin people’s living culture has a unique role in the life H WHICH JOBS? 20 of this region. THE JOBS PLAN 21 THE AMENITY PLAN 22 THE TRANSPORT PLAN 23 THE EDUCATION PLAN 24 MORE ON JOBS 25 • Health care and social assistance • Construction and manufacturing • Justice and government precinct • Airport, tourism and business services • Retail Sources: Data from the ABS, the Victorian government population projections, and the LGA level employment data from .id demographic resources. -

Brimbank City Local Facilities the Lake Reserve

Brimbank City The City of Brimbank is a local government area located within the metropolitan area of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It comprises the western suburbs between 10 and 20 km west and northwest from the Melbourne city centre. Local Facilities The Lake Reserve Chichester Drive, Taylors Lakes Bus 476 The main playground structure at the Lakes Reserve District Park is in the shape of a fish and offers great play opportunities for all children. This park is one of five flagship parks of Council’s much improved park network, and is a key milestone in the implementation of Creating Better Parks. Delahay Recreation Reserve 36A Goldsmith Avenue Bus 422 & 425 In April 2013 Council completed the upgrade of the Delahey Recreation Reserve Suburban Park playground. This upgrade, which is part of implementing our Creating Better Parks Policy and Plan, has provided the community with an attractively landscaped play space offering a range of play opportunities for children. St Albans Leisure Center 90 Taylors Road Sydenham Library 1 Station Street, Taylors Lakes Sydenham Library is located is on the ground floor of the Sydenham Community Hub in Watergardens. It has a self-contained Council Customer Service point and spacious study areas. There is an additional computer and study area available to library members on the first floor of the Sydenham Community Hub. Dear Park Library 4 Neale Road, Deer Park Deer Park Library is located next to the Brimbank Central Shopping Centre. It offers quiet individual study rooms, collections in community languages, a toy library, and an outside children’s play area.