Asia Between Multipolarism and Multipolarity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 15, 2020 Ambassador Robert E. Lighthizer U.S. Trade

July 15, 2020 Ambassador Robert E. Lighthizer U.S. Trade Representative 600 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20508 Re: Docket No. USTR-2020-0022: Initiation of Section 301 Investigations of Digital Services Taxes Dear Ambassador Lighthizer: The Information Technology Industry Council (ITI) welcomes the U.S. Administration’s recognition that digital services taxes (DSTs) that have been adopted or are under consideration in ten jurisdictions – Austria, Brazil, the Czech Republic, the European Union (EU), India, Indonesia, Italy, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom (UK) – raise concerns under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. These unilateral measures advance a troubling precedent, unnecessarily depart from progress toward stable and sustainable international tax policies, and will disproportionately impact U.S.-headquartered companies. In accordance with the notice and request for comments published by the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) on June 5, 2020, ITI respectfully submits the following written comments on the Administration’s initiation of Section 301 investigations of these ten measures.1 In our comments, we provide USTR with evidence to support a determination that these new DSTs – like the French DST – are unfair trade practices under Section 301 because they are discriminatory, unreasonable, inconsistent with prevailing international tax principles, and unusually burdensome for affected U.S. companies. Notably, many of the DSTs are structured similarly to the French DST and share the same problematic features that USTR identified in its Report on France’s Digital Services Tax (French DST Report),2 including scope limitations and revenue thresholds that are meant to target U.S. companies and shield domestic companies. -

Accidental Prime Minister

THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE MAKING AND UNMAKING OF MANMOHAN SINGH SANJAYA BARU VIKING Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Group (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Offi ce Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in Viking by Penguin Books India 2014 Copyright © Sanjaya Baru 2014 All rights reserved 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verifi ed to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. ISBN 9780670086740 Typeset in Bembo by R. Ajith Kumar, New Delhi Printed at Thomson Press India Ltd, New Delhi This book is sold subject to the condition that -

Anne, Le Musical Viel Chante Brel Et Du West-End Frères Jacques

ÉDITO MUSICALS MAGAZINE est édité par Matthieu Gallou Entertainment 14, rue Cavé, 75018 Paris N°9 - PRinTemPS 2009 EN ATTendanT L'ÉTÉ... Tirage : 1 000 exemplaires Directeur de la publication : À l’heure où nous imprimons ce numéro, nous ne pouvons pas encore vous annoncer la pro- Matthieu Gallou grammation officielle du festival Les Musicals qui se tiendra à Paris du 6 au 26 juillet 2009. Ce Rédacteur en chef : Matthieu Gallou Rédactrice en chef adjointe : sera chose faite début avril sur le site www.lesmusicals.com. Par contre, nous connaissons l’am- Geneviève Krieff pleur de la programmation : entre 25 et 30 musicals, tous genres confondus (tout public, jeune Rédacteurs : Vanessa Bertran - Gilles de Lesdain public, comédies musicales, spectacles musicaux, opérettes) et plus de 200 représentations ! Gabriel Elian - Dorothée Gallou Les organisateurs ont aussi déterminé un tarif unique pour tous les spectacles : 19€. Ce qui Benjamin Giraud - Anne-Marie Hallynck Nicolas Maille - Hélène Milon permet d’accéder à des spectacles de premier ordre et normalement affichés à 30, 35 € la place. Michel Pouradier - Sébastien Riché Ceux qui ne partent pas en vacances, ceux qui travaillent encore, mais aussi les jeunes et les Christine Sabban - Tomoko Sawauchi Nicolas Williamson séniors pourront ainsi s’offrir des sorties à portée de leurs moyens. Secrétaire de redaction : Josée Krieff - Anne-Marie Hallynck La fin de saison approche et les récompenses commencent à être distribuées. Hélène Milon Conception graphique Après les Césars, les Oscars, les Tony Awards, les Victoires de la Musique et et mise en page : Geneviève Krieff les Molières, se profile la cérémonie des Marius, honorant les (www.genevievekrieff.com) meilleurs musicals de l’année et les meilleurs interprètes. -

Online Newshour and Newshour Extra Release

Using NewsHour Extra Feature Stories STORY What Does Lady Gaga’s Asia Tour Say About the Global Economy? 05/14/2012 http://www.pbs.org/newshour/extra/features/arts/jan-june12/gaga_05-14.html Estimated Time: One 45-minute class period with possible extension Student Worksheet (reading comprehension and discussion questions without answers) PROCEDURE 1. WARM UP Use initiating questions to introduce the topic and find out how much your students know. 2. MAIN ACTIVITY Have students read NewsHour Extra's feature story and answer the reading comprehension and discussion questions on the student handout. 3. DISCUSSION Use discussion questions to encourage students to think about how the issues outlined in the story affect their lives and express and debate different opinions.] INITIATING QUESTIONS 1. Why do musicians go on tour? 2. What do you know about Asia and its culture? 3. How do musicians like Lady Gaga make money? READING COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS – Student Worksheet 1. Where did Lady Gaga kick off her tour for the album “Born This Way?” Seoul, South Korea 2. Where else will the tour stop? Hong Kong, Taiwan’s Taipei, Jakarta in Indonesia, Singapore, and Bangkok in Thailand 3. What Asian country has always been a destination for successful music artists? Japan 4. Who is encouraging people to boycott Lady Gaga’s concerts? Religious groups from Christians in Korea to Muslims in Indonesia 5. How many tickets to Lady Gaga’s show were sold in the first two hours in Jakarta? 25,000 6. What is the new minimum age for people to attend Lady Gaga’s concerts in South Korea? 18 years old http://www.pbs.org/newshour/extra/ 1 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS (more research might be needed) 1. -

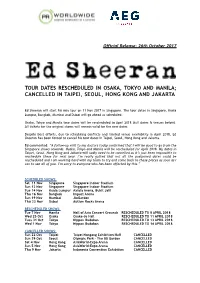

Ed Sheeran Asia Tour Dates Revised

Official Release; 26th October 2017 TOUR DATES RESCHEDULED IN OSAKA, TOKYO AND MANILA; CANCELLED IN TAIPEI, SEOUL, HONG KONG AND JAKARTA Ed Sheeran will start his Asia tour on 11 Nov 2017 in Singapore. The tour dates in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, Mumbai and Dubai will go ahead as scheduled. Osaka, Tokyo and Manila tour dates will be rescheduled to April 2018 (full dates & venues below). All tickets for the original shows will remain valid for the new dates. Despite best efforts, due to scheduling conflicts and limited venue availability in April 2018, Ed Sheeran has been forced to cancel his tour dates in Taipei, Seoul, Hong Kong and Jakarta. Ed commented: “A follow-up visit to my doctors today confirmed that I will be good to go from the Singapore shows onwards. Osaka, Tokyo and Manila will be rescheduled for April 2018. My dates in Taipei, Seoul, Hong Kong and Jakarta will sadly need to be cancelled as it’s just been impossible to reschedule these for next year. I’m really gutted that not all the postponed dates could be rescheduled and I am working hard with my team to try and come back to these places as soon as I can to see all of you. I’m sorry to everyone who has been affected by this.” SCHEDULED SHOWS: Sat 11 Nov Singapore Singapore Indoor Stadium Sun 12 Nov Singapore Singapore Indoor Stadium Tue 14 Nov Kuala Lumpur Axiata Arena, Bukit Jalil Thu 16 Nov Bangkok Impact Arena Sun 19 Nov Mumbai JioGarden Thu 23 Nov Dubai Autism Rocks Arena RESCHEDULED SHOWS: Tue 7 Nov Manila Mall of Asia Concert Grounds RESCHEDULED TO 8 APRIL 2018 Wed 25 Oct Osaka Osaka-Jo Hall RESCHEDULED TO 11 APRIL 2018 Tues 31 Oct Tokyo Nippon Budokan RESCHEDULED TO 13 APRIL 2018 Wed 1 Nov Tokyo Nippon Budokan RESCHEDULED TO 14 APRIL 2018 CANCELLED SHOWS: Sun 22 Oct Taipei Taipei Nangang Exhibition Hall CANCELLED Sun 29 Oct Seoul Olympic Park – The 88 Garden CANCELLED Sat 4 Nov Hong Kong AsiaWorld-Expo Arena CANCELLED Sun 5 Nov Hong Kong AsiaWorld-Expo Arena CANCELLED Thu 9 Nov Jakarta Indonesia Convention Exhibition CANCELLED. -

Sri Mulyani Indrawati, S.E., M.Sc., Ph.D

Image not found or type unknown Sri Mulyani Indrawati, S.E., M.Sc., Ph.D Plt. Menteri Koordinator Bidang Perekonomian RI Sri Mulyani Indrawati lahir di Bandar Lampung, Lampung, pada tanggal 26 Agustus 1962. Ia adalah wanita sekaligus orang Indonesia pertama yang menjabat sebagai Direktur Pelaksana Bank Dunia. Jabatan ini diembannya mulai 1 Juni 2010. Sebelumnya, dia menjabat Menteri Keuangan, Kabinet Indonesia Bersatu. Ketika ia menjadi Direktur Pelaksana Bank Dunia, maka ia pun meninggalkan jabatannya sebagai Menteri Keuangan. Sebelum menjadi Menteri Keuangan, Ia menjabat sebagai Menteri Negara Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional/Bappenas dari Kabinet Indonesia Bersatu. Sri Mulyani sebelumnya dikenal sebagai seorang pengamat ekonomi di Indonesia. Ia menjabat sebagai Kepala Lembaga Penyelidikan Ekonomi dan Masyarakat Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Indonesia (LPEM FEUI) sejak Juni 1998. Pada 5 Desember 2005, ketika Presiden Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono mengumumkan perombakan kabinet, Sri Mulyani dipindahkan menjadi Menteri Keuangan menggantikan Jusuf Anwar. Sejak tahun 2008, ia menjabat Pelaksana Tugas Menteri Koordinator Bidang Perekonomian, setelah Menteri Koordinator Bidang Perekonomian Boediono dilantik sebagai Gubernur Bank Indonesia. Ia dinobatkan sebagai Menteri Keuangan terbaik Asia untuk tahun 2006 oleh Emerging Markets pada 18 September 2006 di sela Sidang Tahunan Bank Dunia dan IMF di Singapura. Ia juga terpilih sebagai wanita paling berpengaruh ke-23 di dunia versi majalah Forbes tahun 2008 dan wanita paling berpengaruh ke-2 di Indonesia -

8-11 July 2021 Venice - Italy

3RD G20 FINANCE MINISTERS AND CENTRAL BANK GOVERNORS MEETING AND SIDE EVENTS 8-11 July 2021 Venice - Italy 1 CONTENTS 1 ABOUT THE G20 Pag. 3 2 ITALIAN G20 PRESIDENCY Pag. 4 3 2021 G20 FINANCE MINISTERS AND CENTRAL BANK GOVERNORS MEETINGS Pag. 4 4 3RD G20 FINANCE MINISTERS AND CENTRAL BANK GOVERNORS MEETING Pag. 6 Agenda Participants 5 MEDIA Pag. 13 Accreditation Media opportunities Media centre - Map - Operating hours - Facilities and services - Media liaison officers - Information technology - Interview rooms - Host broadcaster and photographer - Venue access Host city: Venice Reach and move in Venice - Airport - Trains - Public transports - Taxi Accomodation Climate & time zone Accessibility, special requirements and emergency phone numbers 6 COVID-19 PROCEDURE Pag. 26 7 CONTACTS Pag. 26 2 1 ABOUT THE G20 Population Economy Trade 60% of the world population 80 of global GDP 75% of global exports The G20 is the international forum How the G20 works that brings together the world’s major The G20 does not have a permanent economies. Its members account for more secretariat: its agenda and activities are than 80% of world GDP, 75% of global trade established by the rotating Presidencies, in and 60% of the population of the planet. cooperation with the membership. The forum has met every year since 1999 A “Troika”, represented by the country that and includes, since 2008, a yearly Summit, holds the Presidency, its predecessor and with the participation of the respective its successor, works to ensure continuity Heads of State and Government. within the G20. The Troika countries are currently Saudi Arabia, Italy and Indonesia. -

Akhmad Rizal Shidiq

3963 Persimmon Drive, Apt 103 Fairfax, VA 22031 Tel: +1 (571) 282-5387 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://scholar.harvard.edu/rizalshidiq/ Akhmad Rizal Shidiq Research Economist by training and currently working on Ph.D dissertation on financial crisis, Interest credit market, firms, and political connections in Indonesia. Primary fields are monetary theory and public choice. Extensive research experience especially in development mi- croeconomics, political economy, and trade. Conducted field researches and large-survey analysis in Indonesia, with substantial experience in working with government and inter- national agencies. Taught intermediate micro and macroeconomics for undergraduate. Education George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia USA Ph.D., Economics (expected Spring 2015) Dissertation Topic: \Essays on Firms and Political Connections in Indonesia" SOAS, University of London, UK M.Sc., Development Economics 2002 University of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia Sarjana (B.A.), Economics 1999 Academic Harvard Kennedy School, Cambridge, Massachusetts USA Experience Research Fellow 2011 - 2013 Pre-doctoral research fellowship George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia USA Graduate Lecturer 2010 Intermediate Macroeconomics for undergraduate Department of Economics, University of Indonesia, Jakarta Indonesia Lecturer 2006-2007 Indonesian Economic Policy and Poverty, Income Distribution, and Public Policy courses in Master of Public Policy Program Lecturer 2002-2007 Intermediate Micro and Macroeconomics for undergraduate Teaching -

Student Recruitment Tour Asia

Student Recruitment Tour Asia East Asia Tour 31 August - 12 September Seoul & Jeju, South Korea Beijing & Shanghai, China 2019 Taipei, Taiwan Hong Kong, SAR China Hanoi, Vietnam Southeast Asia Tour 9 - 20 September Hanoi & Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Phnom Penh & Siem Reap, Cambodia Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Jakarta, Indonesia Singapore, Singapore Full Asia Tour 31 August - 20 September Includes both East and Southeast Asia tours Shaping the future of international education 2018 TOUR 36 Schools Visited 4,600 Students Seen ABOUT THE TOUR By joining the CIS Asia Tour 2019, you’ll gain opportunities to interact with thousands of students from a diverse range of high schools and educational backgrounds, exposing them to the breadth of opportunity available at institutions of higher learning around the world. Our goal is to maximize opportunities for university representatives, meeting the needs of a broad range of institutional enrolment priorities. In addition to offering university fairs in high schools, the tour will provide travelers with the opportunity to facilitate educational workshops on a variety of topics for prospective students and counsellors in the schools. Tour participants will also take part in counsellor programmes offered in Shanghai, China and Siem Riep, Cambodia. Counsellor programs are designed to help university representatives build meaningful relationships with school counsellors from the region through facilitated conversations, workshops, and shared experiences. 2 [email protected] | www.cois.org WHAT MAKES CIS TOURS UNIQUE? CIS TOURS HAVE STOOD THE TEST OF TIME CIS is a non-profit organization that has been sponsoring recruitment tours for nearly 40 years. Our tour leaders are experienced admissions professionals working at CIS member universities. -

H-Diplo Roundtables, Vol. XIV, No. 28

2013 Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane H-Diplo Labrosse Roundtable Web/Production Editor: George Fujii H-Diplo Roundtable Review Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Volume XIV, No. 28 (2013) Introduction by Donal O’Sullivan, California State 22 April 2013 University Northridge Geoffrey Roberts. Molotov: Stalin’s Cold Warrior. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2011. ISBN: 978-1-57488-945-1 (cloth, $29.95). Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XIV-28.pdf Contents Introduction by Donal O’Sullivan, California State University Northridge ............................... 2 Review by Alexei Filitov, Institute of World History, Russian Academy of Sciences ................ 5 Review by Jonathan Haslam, Cambridge University ................................................................ 8 Review by Jochen Laufer, Potsdamer Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung ...................... 13 Review by Wilfried Loth, University of Duisburg-Essen .......................................................... 18 Author’s Response by Geoffrey Roberts, University College Cork Ireland ............................. 21 Copyright © 2013 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. XIV, No. 28 (2013) Introduction by Donal O’Sullivan, California State University Northridge emarkably, until recently Joseph Stalin’s closest aide, Vyacheslav Molotov, has rarely been the subject of serious scholarly interest. Geoffrey Roberts was one of the first R to see Molotov’s files. -

73 Topik : Penyelidikan Sri Mulyani Dan Boediono Oleh KPK Durasi : 03 Menit 20 Detik Sri Mulyani Dimintai Keterangan Sejak

Lampiran 1: Transkrip Pemberitaan pada Program Kabar Petang 29 April 2010 Topik : Penyelidikan Sri Mulyani dan Boediono oleh KPK Durasi : 03 menit 20 detik Sri Mulyani dimintai keterangan sejak pukul setengah sebelas hingga pukul setengah satu siang di lantai 5 di Gedung Departemen Keuangan. Sri Mulyani diminta keterangan oleh 3 penyidik dari KPK, dipimpin direktur penyelidikan, Iswan Elmi. (SHINTA) { Visual Images : from studio move to video Sri Mulyani turun dari mobil di sebuah parkiran basement dengan pengawalan pihak keamanan tanpa berkomentar apapun dan langsung menuju ke lift} Fokusnya masih pada latar belakang alasan kebijakan menyatakan kondisi ekonomi sedang krisis global dan keluarnya perpu JPSK. Sri mulyani selama ini disebut-sebut yang paling bertanggungjawab terhadap kebijakan pengucuran dana talangan Bank Century senilai 6,7 triliun. Dalam rapat paripurna dewan perwakilan rakyat telah diputuskan opsi C sebagai penyelesaian politis kasus Bank Century. Artinya keputusan DPR menyetujui kebijakan pemberian fasilitas pendanaan jangka pendek atau FPJP dan penyertaan modal sementara (PMS) kepada Bank Century, serta pelaksanaanya bermasalah. (RIZKY) { Visual Images : suasana di lobby gedung departemen keuangan yang ramai oleh kehadiran para pencari berita serta aktifitas para penjaga gedung departemen keuangan yang sedang berjaga di pintu menuju lift dan suasan sekitar} HENGKINUS MANAO ( Direktur Jenderal Dekeu) : “Ya sesuai dengan apa, aaa permintaan dari KPK ya mereka aaa meminta kesediaan menteri keuangan untuk memberi keterangan -

Dartmouth Conf Program

The Dartmouth Conference: The First 50 Years 1960—2010 Reminiscing on the Dartmouth Conference by Yevgeny Primakov T THE PEAK OF THE COLD WAR, and facilitating conditions conducive to A the Dartmouth Conference was one of economic interaction. the few diversions from the spirit of hostility The significance of the Dartmouth Confer- available to Soviet and American intellectuals, ence relates to the fact that throughout the who were keen, and able, to explore peace- cold war, no formal Soviet-American contact making initiatives. In fact, the Dartmouth had been consistently maintained, and that participants reported to huge gap was bridged by Moscow and Washington these meetings. on the progress of their The composition of discussion and, from participants was a pri- time to time, were even mary factor in the success instructed to “test the of those meetings, and it water” regarding ideas took some time before the put forward by their gov- negotiating teams were ernments. The Dartmouth shaped the right way. At meetings were also used first, in the early 1970s, to unfetter actions under- the teams had been led taken by the two countries by professionally quali- from a propagandist connotation and present fied citizens. From the Soviet Union, political them in a more genuine perspective. But the experts and researchers working for the Insti- crucial mission for these meetings was to tute of World Economy and International establish areas of concurring interests and to Relations and the Institute of U.S. and Cana- attempt to outline mutually acceptable solutions dian Studies, organizations closely linked to to the most acute problems: nuclear weapons Soviet policymaking circles, played key roles.