Prevalence of Batrachochytrium Dendrobatidis and B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Incursion Plan PIP006 Salamanders and Newts

Pre-incursion Plan PIP006 Salamanders and Newts Pre-incursion Plan PIP006 Salamanders and Newts Order: Ambystomatidae, Cryptobranchidea and Proteidae Scope This plan is in place to guide prevention and eradication activities and the management of non-indigenous populations of Salamanders and Newts (Order Caudata; Families Salamandridae, Ambystomatidae, Cryptobranchidea and Proteidae) amphibians in the wild in Victoria. Version Document Status Date Author Reviewed By Approved for Release 1.0 First Draft 26/07/11 Dana Price M. Corry, S. Wisniewski and A. Woolnough 1.1 Second Draft 21/10/11 Dana Price S. Wisniewski 2.0 Final Draft 18/01/2012 Dana Price 3.0 Revision Draft 12/11/15 Dana Price J. Goldsworthy 3.1 New Final 10/03/2016 Nigel Roberts D.Price New DEDJTR templates and document review Published by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources, Agriculture Victoria, May 2016 © The State of Victoria 2016. This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources, 1 Spring Street, Melbourne 3000. Front cover: Smooth Newt (Lissotriton vulgaris) Photo: Image courtesy of High Risk Invasive Animals group, DEDJTR Photo: Image from Wikimedia Commons and reproduced with permission under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic License. ISBN 078-1-925532-40-1 (pdf/online) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Necturus Maculosus)

MINNESOTA PROFILE Mlldplippy (Necturus maculosus) Appearance The mudpuppy is Minnesota's largest salamander species, with adults reaching lengths of 13 inches or more. Brown or grayish in color, the mudpuppy has spots peppered across its back and sides, and its underside is light gray or buff. Hatchlings and juveniles have a yellow stripe along each side. The mud- puppy has small eyes and a paddlelike tail, which it uses to propel itself during rapid swimming. The sides of the head are adorned with bushy, red gills, that are bright red and conspicuous when in heavily oxygenated water, but are smaller, more compressed, and darker colored when in low-oxygenated water. Tiger salamander larvae are often mistaken for mudpuppies because they have a similar body structure and external gills.The best distinguishing trait: Mudpuppies have four toes on each hind foot, and larval tiger salamanders have five. People often refer to mudpuppies as waterdogs or axolotls, but true waterdogs and axolotls are not found in Minnesota. Range Mudpuppies are found primarily in the eastern United States.Their range extends from southeastern Manitoba and southern Quebec, to eastern Kansas, and to northern Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. In Minnesota, mudpuppies inhabit the Mississippi, St. Croix, Minnesota, and Red river drainages. Most recorded sightings have been on the state's eastern and western edges, except for a few records along the Minnesota River. Habitat Minnesota's only fully aquatic salamander species, the mudpuppy lives in water during every stage of its life cycle. In eastern Minnesota they appear to prefer rivers with rocky or gravelly substrates. -

Final Study Plan

F INAL REPORT Black Warrior Waterdog Field Survey and Habitat Assessment William Bacon Oliver Lake, Holt Dam Tailrace Tuscaloosa County, Alabama 13 February 2015 Prepared for ALABAMA POWER COMPANY By Mark A. Bailey CONSERVATION SOUTHEAST 7746 Boggan Level Road Andalusia, AL 36420 BLACK WARRIOR WATERDOG SURVEY, HOLT DAM TAILRACE Executive Summary Trapping and visual habitat surveys were conducted for the Black Warrior Waterdog (Necturus alabamensis) in the mouth and lowermost reach of Yellow Creek and the tailrace below Holt Dam. Fieldwork was conducted on 3 through 5 February 2015 by biologists Mark Bailey of Conservation Southeast and Chad Fitch of Alabama Power Company Environmental Affairs. The absence of leaf packs precluded dip-net surveys and 30 minnow traps baited with chicken livers were employed, 20 along the main river channel shore and 10 in Yellow Creek. After 60 trap-nights (990 trap-hours), no Black Warrior Waterdogs were captured. Habitat conditions were considered poor but not entirely unsuitable. Contributing to the poor conditions are heavy sedimentation in Yellow Creek and the altered Black Warrior River channel at what is now William Bacon Oliver Lake. I BLACK WARRIOR WATERDOG SURVEY, HOLT DAM TAILRACE Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... i Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 The Black Warrior Waterdog ............................................................................................................. -

2020 SE PARC Oral Abstract Booklet Abstracts Are Listed Alphabetically by First Author’S Last Name

2020 SE PARC Oral Abstract Booklet Abstracts are listed alphabetically by first author’s last name. Presenting author is denoted with an asterisk. TROPHIC AND COMMUNITY STRUCTURE OF SNAKE ASSEMBLAGES IN SHORTLEAF PINE FORESTS WITH DIFFERENT MANAGEMENT REGIMES. Connor S. Adams1*, Christopher M. Schalk1, Daniel Saenz2 1Stephen F. Austin State University; 2USFS Southern Research Station Land-use practices such as intensive silviculture and fire suppression are common in shortleaf pine forests of eastern Texas. These practices have contributed to the loss of shortleaf pine savannahs that were once widespread throughout the southeast. Fortunately, there is a renewed interest in restoring these ecosystems through the application of forest management techniques (i.e., prescribed fire, thinning). While these applications have been shown to alter forest structure, there is little known about how these efforts influence energy flow and the consumer- resource relationships that determine community structure. Here we present the results on the trophic structure of snake communities at two shortleaf pine sites under different management regimes (high-frequency [A] vs. low-frequency [B]). We captured snakes from May-July in 2018 and 2019 using box traps and drift fences. At each trap we measured 7 habitat variables, and collected dominant basal resources and potential prey. Using stable isotope analysis, we compared community-wide metrics of trophic structure and performed isotopic mixing-models to determine the relative contribution of resources to snake consumers. We found that snakes species from site A exhibited increased trophic redundancy. At site B, we observed trophic divergence between snake species, with species supported by a wider range of resources and relative tropic positions. -

AMPHIBIANS of OHIO F I E L D G U I D E DIVISION of WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION

AMPHIBIANS OF OHIO f i e l d g u i d e DIVISION OF WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION Amphibians are typically shy, secre- Unlike reptiles, their skin is not scaly. Amphibian eggs must remain moist if tive animals. While a few amphibians Nor do they have claws on their toes. they are to hatch. The eggs do not have are relatively large, most are small, deli- Most amphibians prefer to come out at shells but rather are covered with a jelly- cately attractive, and brightly colored. night. like substance. Amphibians lay eggs sin- That some of these more vulnerable spe- gly, in masses, or in strings in the water The young undergo what is known cies survive at all is cause for wonder. or in some other moist place. as metamorphosis. They pass through Nearly 200 million years ago, amphib- a larval, usually aquatic, stage before As with all Ohio wildlife, the only ians were the first creatures to emerge drastically changing form and becoming real threat to their continued existence from the seas to begin life on land. The adults. is habitat degradation and destruction. term amphibian comes from the Greek Only by conserving suitable habitat to- Ohio is fortunate in having many spe- amphi, which means dual, and bios, day will we enable future generations to cies of amphibians. Although generally meaning life. While it is true that many study and enjoy Ohio’s amphibians. inconspicuous most of the year, during amphibians live a double life — spend- the breeding season, especially follow- ing part of their lives in water and the ing a warm, early spring rain, amphib- rest on land — some never go into the ians appear in great numbers seemingly water and others never leave it. -

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List

Section IV – Guideline for the Texas Priority Species List Associated Tables The Texas Priority Species List……………..733 Introduction For many years the management and conservation of wildlife species has focused on the individual animal or population of interest. Many times, directing research and conservation plans toward individual species also benefits incidental species; sometimes entire ecosystems. Unfortunately, there are times when highly focused research and conservation of particular species can also harm peripheral species and their habitats. Management that is focused on entire habitats or communities would decrease the possibility of harming those incidental species or their habitats. A holistic management approach would potentially allow species within a community to take care of themselves (Savory 1988); however, the study of particular species of concern is still necessary due to the smaller scale at which individuals are studied. Until we understand all of the parts that make up the whole can we then focus more on the habitat management approach to conservation. Species Conservation In terms of species diversity, Texas is considered the second most diverse state in the Union. Texas has the highest number of bird and reptile taxon and is second in number of plants and mammals in the United States (NatureServe 2002). There have been over 600 species of bird that have been identified within the borders of Texas and 184 known species of mammal, including marine species that inhabit Texas’ coastal waters (Schmidly 2004). It is estimated that approximately 29,000 species of insect in Texas take up residence in every conceivable habitat, including rocky outcroppings, pitcher plant bogs, and on individual species of plants (Riley in publication). -

2017 Hellbender Symposium Agenda

Mississippi Museum of Natural Science 2148 Riverside Drive, Jackson, Mississippi June 19-21, 2017 Page 1 Artwork for the symposium logo was kindly provided by the Mississippi Museum of Natural Science’s in-house artist, Sam Beibers. You are welcome to use this illustration as long as it is not used for resale in any capacity. Please credit its use with the following: "Illustration: Sam Beibers". IF you need illustrations for any of your own projects, you may contact Sam at 601-826-9256 or [email protected]. In this illustration, Sam Beibers wanted to take a "color challenged" animal in situ and push those colors brighter than they normally would be. "I wanted the hellbender to have something of a regal look. Afterall, they are 'superstars' to many of us in the scientific community." The final illustration was painted in watercolor on thin, clay-coated bristol board. As the paint dries on a smooth surface that is not very porous, the paint tends to "sit" on the surface instead of soaking in. Therefore it often dries in visible puddles. Pencil was used to add some detail and emphasize some areas of shade. Beibers grew up in rural northwest Mississippi. Like most boys, he enjoyed catching tadpoles, building huts, and swinging on grapevines. After one miserable year of wildlife biology studies at junior college, he changed his major to art and has since gone on to paint and draw hundreds of flora and fauna illustrations, as well as landscapes, cityscapes, and portraits. He received his MA at Mississippi College. Page 2 The following sponsors (and/or representatives from these institutions) helped make this symposium a success. -

Mudpuppy Assessment Along the St. Clair-Detroit River System 2

1 Mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus) Assessment Along the St. Clair-Detroit River System Prepared by Herpetological Resource & Management, LLC Mudpuppy Assessment Along the St. Clair-Detroit River System 2 2. IntroductionAcknowledgements Suggested Citation: Stapleton, M.M., D.A. Mifsud, K. Greenwald, Boase, J., Bohling, M., Briggs, A., Chiotti, J., Craig, J., Kennedy, G., Kik IV, R., Hessenauer, J.M., Leigh, D., Roseman, E., Stedman, A., Sutherland, J., and Thomas, M. 2018. Mudpuppy Assessment Along the St. Clair-Detroit River System. Herpetological Resource and Management Technical Report. 110 pp. Funding for this project was provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the Great Lakes Fish and Wildlife Restoration Act. The authors would like to thank the following people for their support of this project through dedicated time and resources: Zachary Barnes, Stephen Beyer, Christine Bishop, Kiley Briggs, Tricia Brockman, Amanda Bryant, Ryan Colliton, Jean-Franois Desroches, David Dortman, Rose Ellison, Megan English, Jason Fischer, Jason Folt, Melanie Foose, James Francis, James Harding, Taylor Heard, Terry Heatlie, Marisa Hildebrandt, Cynthia Hudson, Scott Jackson, Jennifer Johnson, Cheryl Kaye, Zachary Kellogg, Kristen Larson, Jeff LeClere, Melissa Lincoln, Tim Matson, the MDNR R/V Channel Cat crew, Joshua Miller, Paul Muelle, Mason Murphy, Andrew Nowicki, Sarah Pechtel, Lori Sargent, Greg Schneider, Michelle Seltzer, Alicia Stowe, Alyssa Swinehart, Anna Veltman, Patrick Walker, Rick Westerhof, Michael Wilkinson, and Sean Zera. Thanks go to the numerous organizations that helped make this project possible: Belle Isle Aquarium, Belle Isle Nature Center, Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Michigan Sea Grant, Michigan State University, Missouri Department of Natural Resources, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Potter Park Zoo, University of Michigan, U.S. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Rare Animals Tracking List

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) ‐ Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals ‐ 2020 MOLLUSKS Common Name Scientific Name G‐Rank S‐Rank Federal Status State Status Mucket Actinonaias ligamentina G5 S1 Rayed Creekshell Anodontoides radiatus G3 S2 Western Fanshell Cyprogenia aberti G2G3Q SH Butterfly Ellipsaria lineolata G4G5 S1 Elephant‐ear Elliptio crassidens G5 S3 Spike Elliptio dilatata G5 S2S3 Texas Pigtoe Fusconaia askewi G2G3 S3 Ebonyshell Fusconaia ebena G4G5 S3 Round Pearlshell Glebula rotundata G4G5 S4 Pink Mucket Lampsilis abrupta G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Plain Pocketbook Lampsilis cardium G5 S1 Southern Pocketbook Lampsilis ornata G5 S3 Sandbank Pocketbook Lampsilis satura G2 S2 Fatmucket Lampsilis siliquoidea G5 S2 White Heelsplitter Lasmigona complanata G5 S1 Black Sandshell Ligumia recta G4G5 S1 Louisiana Pearlshell Margaritifera hembeli G1 S1 Threatened Threatened Southern Hickorynut Obovaria jacksoniana G2 S1S2 Hickorynut Obovaria olivaria G4 S1 Alabama Hickorynut Obovaria unicolor G3 S1 Mississippi Pigtoe Pleurobema beadleianum G3 S2 Louisiana Pigtoe Pleurobema riddellii G1G2 S1S2 Pyramid Pigtoe Pleurobema rubrum G2G3 S2 Texas Heelsplitter Potamilus amphichaenus G1G2 SH Fat Pocketbook Potamilus capax G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Inflated Heelsplitter Potamilus inflatus G1G2Q S1 Threatened Threatened Ouachita Kidneyshell Ptychobranchus occidentalis G3G4 S1 Rabbitsfoot Quadrula cylindrica G3G4 S1 Threatened Threatened Monkeyface Quadrula metanevra G4 S1 Southern Creekmussel Strophitus subvexus -

Mud Puppy (Necturus)

Mud Puppy (Necturus) Species: maculosus Genus: Necturus Family: Proteidae Order: Caudata Class: Amphibia Subphylum: Vertebrata Phylum: Chordata Kingdom: Animalia Conditions for Customer Ownership We hold permits allowing us to transport these organisms. To access permit conditions, click here. Never purchase living specimens without having a disposition strategy in place. An end-user permit is required in order to receive Necturus maculosus into Oregon. Shipments of Necturus maculosus are restricted in Ohio. In order to protect our environment, never release a live laboratory organism into the wild. Primary Hazard Considerations • Always wash your hands thoroughly after you handle your organism. • Handle your mud puppy with care—they don’t bark (as once believed) but they can bite! If the skin is broken from a mud puppy bite, disinfect the wound, using soap and warm water. Availability • Mud puppies are wild collected from Lake Erie and are generally available late December through April. Larger than most salamanders, mud puppies can reach a length of 30 centimeters, have external gills, and are dark colored. • Mud puppies will arrive in a sealed plastic bag (double-bagged) filled with water and oxygen. Since oxygen will be continuously depleted, your mud puppy’s good health will be best preserved by moving it into its new home as soon as you receive it. • Open the shipping bag and float it in the aquarium the mud puppy will inhabit. When the water inside the bag is the same temperature as the water in the aquarium (after about 15-30 minutes), transfer the mud puppy from the bag to the tank. -

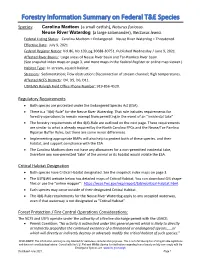

Forestry Information Summary on Federal T&E Species

Forestry Information Summary on Federal T&E Species Species: Carolina Madtom (a small catfish), Noturus furiosus. Neuse River Waterdog (a large salamander), Necturus lewisi. Federal Listing Status: Carolina Madtom = Endangered. Neuse River Waterdog = Threatened. Effective Date: July 9, 2021. Federal Register Notice: Vol.86, No.109, pg.30688-30751. Published Wednesday / June 9, 2021. Affected River Basins: Large areas of Neuse River basin and Tar-Pamlico River basin. (See snapshot index maps on page 3, and more maps in the Federal Register or online map viewer.) Habitat Type: In-stream, aquatic habitat. Stressors: Sedimentation; Flow obstruction; Disconnection of stream channel; High temperatures. Affected NCFS Districts: D4, D5, D6, D11. USF&WS Raleigh Field Office Phone Number: 919-856-4520. Regulatory Requirements • Both species are protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). • There is a “4(d)-Rule” for the Neuse River Waterdog. That rule includes requirements for forestry operations to remain exempt from permitting in the event of an “incidental take”. • The forestry requirements of the 4(d)-Rule are outlined on the next page. These requirements are similar to what is already required by the North Carolina FPGs and the Neuse/Tar-Pamlico Riparian Buffer Rules, but there are some minor differences. • Implementing appropriate BMPs will also help to protect both of these species, and their habitat, and support compliance with the ESA. • The Carolina Madtom does not have any allowances for a non-permitted incidental take, therefore any non-permitted ‘take’ of the animal or its habitat would violate the ESA. Critical Habitat Designation • Both species have Critical Habitat designated.