Helicopter Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-21B) Chapter 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Linearization and Neural Networks

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Department of Electrical and Computer Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Technical Reports Engineering August 1991 Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Linearization and Neural Networks Tobias J. Pallett Purdue University School of Electrical Engineering Shaheen Ahmad Purdue University School of Electrical Engineering Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ecetr Pallett, Tobias J. and Ahmad, Shaheen, "Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Linearization and Neural Networks" (1991). Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Technical Reports. Paper 317. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ecetr/317 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Linearization and Neural Networks Tobias J. Pallett Shaheen Ahmad TR-EE 91-35 August 1991 Real-Time Helicopter Flight Control: Modelling and Control by Lineal-ization and Neural Networks Tobias J. Pallett and Shaheen Ahmad Real-Time Robot Control Laboratory, School of Electrical Engineering, Purdue University West Lafayette, IN 47907 USA ABSTRACT In this report we determine the dynamic model of a miniature helicopter in hovering flight. Identification procedures for the nonlinear terms are also described. The model is then used to design several linearized control laws and a neural network controller. The controllers were then flight tested on a miniature helicopter flight control test bed the details of which are also presented in this report. Experimental performance of the linearized and neural network controllers are discussed. -

Helicopter Physics by Harm Frederik Althuisius López

Helicopter Physics By Harm Frederik Althuisius López Lift Happens Lift Formula Torque % & Lift is a mechanical aerodynamic force produced by the Lift is calculated using the following formula: 2 = *4 '56 Torque is a measure of how much a force acting on an motion of an aircraft through the air, it generally opposes & object causes that object to rotate. As the blades of a Where * is the air density, 4 is the velocity, '5 is the lift coefficient and 6 is gravity as a means to fly. Lift is generated mainly by the the surface area of the wing. Even though most of these components are helicopter rotate against the air, the air pushes back on the rd wings due to their shape. An Airfoil is a cross-section of a relatively easy to measure, the lift coefficient is highly dependable on the blades following Newtons 3 Law of Motion: “To every wing, it is a streamlined shape that is capable of generating shape of the airfoil. Therefore it is usually calculated through the angle of action there is an equal and opposite reaction”. This significantly more lift than drag. Drag is the air resistance attack of a specific airfoil as portrayed in charts much like the following: reaction force is translated into the fuselage of the acting as a force opposing the motion of the aircraft. helicopter via torque, and can be measured for individual % & -/ 0 blades as follows: ! = #$ = '()*+ ∫ # 1# , where $ is the & -. Drag Force. As a result the fuselage tends to rotate in the Example of a Lift opposite direction of its main rotor spin. -

Paper Helicopters Preparation

Paper Helicopters Preparation CLASS LEVEL First – sixth class OBJECTIVES Content Strand and Strand Unit Energy & forces, Forces Through investigation the child should be enabled to come to appreciate that gravity is a force, SESE: Science Curriculum page 87. In this activity children explore how some things fall and how varying the size of the rotor blades, the shape of the rotor blades and the weight of a paper helicopter affect the way a helicopter spins. Skill development Through completing the strand units of the science curriculum the child should be enabled to design, plan and carry out simple experiments, having regard to one or two variables and the need to sequence tasks and tests, SESE: Science Curriculum page 79. This activity helps them understand fair testing by changing only one variable (i.e. shape only or length only) at a time. Investigating; experimenting; observing; analysing; measuring/timing; recording and communicating. CURRICULUM LINKS Mathematics Data / representing and interpreting data SESE: History Continuity and change over time/ technological and scientific developments over long periods BACKGROUND A previous activity on how things fall (i.e. the weight of the object is not a factor – Galileo and the Leaning Tower of Pisa) would help understanding of this activity, but not essential. MATERIALS/EQUIPMENT Paper, Ruler, Paper Clips, Scissors Templates of different sizes PREPARATION Test out a few thicknesses of paper/cardboard first to see that some of them spin. BACKGROUND The shape of the helicopter rotor blades make it spin INFORMATION when dropped from a height. Gravity pulls the helicopter down. The air resists the movement and pushes up each rotor separately, causing the helicopter to spin. -

Over Thirty Years After the Wright Brothers

ver thirty years after the Wright Brothers absolutely right in terms of a so-called “pure” helicop- attained powered, heavier-than-air, fixed-wing ter. However, the quest for speed in rotary-wing flight Oflight in the United States, Germany astounded drove designers to consider another option: the com- the world in 1936 with demonstrations of the vertical pound helicopter. flight capabilities of the side-by-side rotor Focke Fw 61, The definition of a “compound helicopter” is open to which eclipsed all previous attempts at controlled verti- debate (see sidebar). Although many contend that aug- cal flight. However, even its overall performance was mented forward propulsion is all that is necessary to modest, particularly with regards to forward speed. Even place a helicopter in the “compound” category, others after Igor Sikorsky perfected the now-classic configura- insist that it need only possess some form of augment- tion of a large single main rotor and a smaller anti- ed lift, or that it must have both. Focusing on what torque tail rotor a few years later, speed was still limited could be called “propulsive compounds,” the following in comparison to that of the helicopter’s fixed-wing pages provide a broad overview of the different helicop- brethren. Although Sikorsky’s basic design withstood ters that have been flown over the years with some sort the test of time and became the dominant helicopter of auxiliary propulsion unit: one or more propellers or configuration worldwide (approximately 95% today), jet engines. This survey also gives a brief look at the all helicopters currently in service suffer from one pri- ways in which different manufacturers have chosen to mary limitation: the inability to achieve forward speeds approach the problem of increased forward speed while much greater than 200 kt (230 mph). -

Helicopter and Tiltrotor Noise Modeling Procedures Document

ACRP Problem Statement: 89 Recommended Allocation: $250,000 Helicopter and Tiltrotor Noise Modeling Procedures Document Click here to see problem statement in IdeaHub: http://ideascale.com/t/UKsrZBVBS (Note: you must be a registered user in myACRP/IdeaHub.) TAGS: Airport Planning, Environment, Noise Impacts, Operations, Policy, Public Relations STAFF COMMENTS No comments. AVERAGE INDUSTRY RATING SUMMARY Committees1 Airport Community2 Achievable 3.00 3.50 Applicable 2.50 3.50 Implementable 2.00 3.50 Understandable 2.50 3.00 OVERALL 2.50 3.38 Notes: 1. Includes TRB aviation committees and committees from ACI-NA and AAAE. 2. Includes airport employees serving on active ACRP project panels. CLICK HERE TO SEE DETAILED INDUSTRY RATINGS CLICK HERE TO SEE DETAILED INDUSTRY COMMENTS ACRP OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE (AOC) DISPOSITION The average AOC rating among its voting members was 2.1 on a scale of 1 to 5. There was on discussion. The problem statement was not selected for ACRP funding and will be returned to the idea collection phase of ACRP’s IdeaHub. ACRP Problem Statement: 89 Helicopter and Tiltrotor Noise Modeling Procedures Document TAGS: Airport Planning, Environment, Noise Impacts, Operations, Policy, Public Relations OBJECTIVE The objective of this research effort is to develop written documentation on best available methods to model community noise generated from helicopter and tiltrotor operations. The document should address integrated and simulation modeling techniques, and methods for collecting and analyzing noise source data, and outline noise source development protocols. The language and format of the document shall be suitable for standards submission. BACKGROUND Existing noise modeling standards [SAE-AIR-1845; ICAO, Doc-29] for prediction of fixed wing community noise have been promulgated internationally and serve as the technical justification and defensible rationale upon which numerous noise models such as the Aviation Environmental Design Tool (AEDT) and the Integrated Noise Model (INM) rely. -

The Rotating Wing Aircraft Meetings of 1938 and 1939 Were the First

The Rotating Wing Aircraft Meetings of 1938 and 1939 This advertisement showing Pitcairn’s 1932 Tandem landing at an were the first national conferences on rotorcraft. They marked estate was typical of their strategy to market to the wealthy. “If yours a transition from a technological focus on the Autogiro to the is such an estate or if you will select a neighboring field, a Pitcairn representative will gladly demonstrate the complete practicality of helicopter. In addition, these important meetings helped to this modern American scene.” With the Great Depression wearing lay the groundwork for the founding of the American Heli- on, however, the Autogiro business was moribund by the late 1930s. copter Society. – Ed. he Rotating Wing Aircraft Meeting of October 28 This was a significant gathering for the future of – 29, 1938 at the Franklin Institute in Philadel- rotary wing flight in America, coming at a time when T phia, PA, sponsored by the Philadelphia Chapter the Autogiro movement was moribund and helicopter of the Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences (IAS, the development was just about to receive a boost with forerunner of the American Institute of Aeronautics and commencement of the just-passed Dorsey-Logan Bill. Astronautics, or AIAA), was an historic gathering of And, perhaps of greater importance, those attending – those involved, committed to and researching Autogiro, including many of the leading developers of rotary wing convertiplane and helicopter flight. It was, as described flight – were actively speculating as to the future that in the preface to the conference proceedings, “the first rotary wing flight might take. -

Historical Perspective September 2011 11

Helicopter heroes It was 50 years ago that a prototype helicopter first flew and a legend was born—the CH-47 By Mike Lombardi urrently serving on the front lines The advantage of this unique design Just as earlier Chinooks proved of the global fight against terror- allows for low load-per-rotor area, elimi- themselves in wartime, the D model Cism, the CH-47 Chinook is the nates the need for a tail rotor, increases has played a key role for U.S. and epitome of the innovative tandem-rotor lift and stability, and provides a large allied troops in the deserts of Iraq helicopter designs produced through range for center of gravity. and the mountains of Afghanistan. the genius of helicopter pioneer Frank The HRP was followed by the U.S. The highly modified MH-47 series is Piasecki, founder of the company that Navy HUP/UH-25, the first helicopter to operated by the U.S. Army Special would later develop into the Boeing incorporate overlapping tandem rotors, Operations Forces. operations near Philadelphia. and the U.S. Air Force CH-21, a long- When the Chinook first flew in 1961 The CH-47, having been continuously range helicopter transport designed for Boeing Magazine wrote: “There is a modernized, has provided unmatched use in the Arctic. saying in the aviation industry that you capability for U.S. and allied troops since Piasecki stepped down in 1955 as can tell a winner by its appearance. The hard work and dedication of the Boeing its introduction 50 years ago this month. -

CH-47 Chinook/Improved Cargo Helicopter (CH-47F)

CH-47 Chinook/Improved Cargo Helicopter (CH-47F) 204 United States Army Concept and Technology Development | System Development and Demonstration | Production and Deployment | Operations and Support C H-47 Chinook/Improved Cargo Helicopter (CH-47F) Cargo Chinook/Improved H-47 — Mission — Program Status Transport ground forces, supplies, ammunition and other battle-critical cargo in support • 3QFY98 Awarded the engineering and manufacturing development of worldwide combat and contingency operations. (EMD) contract, slated for completion FY03. T55-GA-714A Engine: — Description and Specifications • 1QFY98 Commenced low-rate initial production (LRIP). As the Army’s only Objective Force heavy-lift cargo helicopter capable of intra-theater cargo movement of payloads greater than 9000 lbs, the CH-47 Chinook/Improved Cargo • 1QFY00 First unit equipped. Helicopter (CH-47F) is an essential component of the Army Vision. The CH-47F program • 2QFY00 Currently fielding for the CH-47D/MH-47D/MH-47E. will remanufacture 300 of the current fleet of 431 CH-47D Chinook helicopters, install a Extended Range Fuel System (ERFS): new digital cockpit, and make modifications to the airframe to reduce vibration. • 4QFY98 Awarded the improved ERFS II production contract. Initial The upgraded cockpit will provide future growth potential and will include a digital data deliveries were deployed in support of operations in Kosovo. bus that permits installation of enhanced communications and navigation equipment for improved situational awareness, mission performance, and survivability. Airframe struc- • 2QFY00 ERFS received a full materiel release. tural modifications will reduce harmful vibrations, reducing operations and support • 3QFY01 First flight (EMD). (O&S) costs and improving crew endurance. Other airframe modifications reduce by approximately 60 percent the time required for aircraft tear down and build-up after — Projected Activities deployment on a C-5 or C-17. -

Current Health Trends in U.S. Military Helicopter and Tiltrotor Pilots: a Triservice Epidemiological Study

Current Health Trends in U.S. Military Helicopter and Tiltrotor Pilots: A Triservice Epidemiological Study John S. Crowley MD MPH US Army Aeromedical Research Laboratory Angelia Cost PhD William Dodson MD MPH Dustin Huber PhD Armed Forces USAF School of Aerospace Medicine Naval Medical Research Unit Health Surveillance Branch Dayton Disclaimers Disclaimer The opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the presenter and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army and/or the U.S. Department of Defense. Citation of trade names in this presentation does not constitute an official Department of the Army endorsement or approval of the use of such commercial items. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. 2 Helicopters are different… “Like all novices we began with the helicopter but soon saw it had no future and dropped it. The helicopter does, with great labor, only what the balloon does without labor…The helicopter is much easier to design than an airplane, but it is worthless when done.” -Wilbur Wright 3 …Helicopter pilots are different too… Helicopter pilots are complicated… The stress of being first… » Helicopter pilots were the first to » Hover » Fly with NVGs » Use the aircraft HMD as primary flight display …Along with all the unique & common stresses of helicopter flight: » Disorientation » Vibration » Head supported mass » Altitude » Hypoxia » G forces » Posture » Fatigue » Workload » Technology 2017 Congressional Tasking SEC. 750. STUDY ON HEALTH OF HELICOPTER AND TILTROTOR PILOTS. (a) STUDY REQUIRED.—The Secretary of Defense shall carry out a study of career helicopter and tiltrotor pilots to assess potential links between the operation of helicopter and tiltrotor aircraft and acute and chronic medical conditions experienced by such pilots. -

Sikorsky Uh-60M Helicopter

SIKORSKY UH-60M BLACK HAWK HELICOPTER This Page Does Not Contain Export Controlled Technical Data BEST-IN-CLASS MULTI-MISSION PERFORMER THE WORLD’S BEST COMBAT ASSAULT/UTILITY HELICOPTER GETS BETTER. Sikorsky has been responding to the needs of the United States Army for nearly a century. The Multi-mission UH-60M is the latest in the BLACK HAWK helicopter product family, more capable, more survivable, more maintainable, more powerful and more effective than its predecessors. The BLACK HAWK helicopter has proven itself both in combat and peace time missions. The UH-60M builds upon its robust predecessors and incorporates design improvements that extends this platform well into the future as the premier combat utility helicopter of choice for the United States as well as 27 other nations. Sikorsky sets the standard for rotorcraft safety and performance, continually developing improvements that make the entire industry safer. The UH-60M BLACK HAWK helicopter is no exception to this and is a safe, cost-effective, top performing helicopter ready to perform your missions. READY FOR BATTLE, TODAY AND TOMORROW. The Sikorsky BLACK HAWK is the primary medium lift helicopter for the U.S. Army performing a wide range of missions that encompass Air Assault, MEDEVAC, CSAR, Command and Control, and VIP transport. The newest version of the Army’s premier combat utility helicopter, the UH-60M, ensures compatibility with the U.S. Army’s Future Force. It will bring new life to the existing fleet, improve their effectiveness, reduce their vulnerability, and allow for future growth while lowering operating and support costs. -

FAA Guide to Low Flying Aircraft

FAA Guide to Low-Flying Aircraft The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the government agency responsible for aviation safety. We welcome information from citizens that will enable us to take corrective measures including legal enforcement action against individuals violating Federal Aviation Regulations (CFR). It is FAA policy to investigate citizen complaints of low-flying aircraft operated in violation of the CFR that might endanger persons or property. Remember that the FAA is a safety organization with legal enforcement responsibilities. We will need facts before we conduct an investigation. To save time, please have this information ready if you witness another low-flying aircraft. Please keep your notes: we may request a written statement. Here is the type of information we need: • Identification – Can you identify the aircraft? Was it military or civil? Was it a high or low wing aircraft? What was the color? Did you record the registration number which appears on the fuselage or tail? (On U.S. registered aircraft, that number will be preceded with a capital "N".) • Time and Place – Exactly when did the incident(s) occur? Where did this happen? What direction was the aircraft flying? • Altitude – How high or low was the aircraft flying? On what do you base your estimate? Was the aircraft level with or below the elevation of a prominent object such as a tower or building? Once we have the appropriate facts, personnel from the Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) will attempt to identify the offending aircraft operator. We can do this in several ways. For example, we can check aircraft flight records with our air traffic control information and/or sightings from other observers, such as local law enforcement officers. -

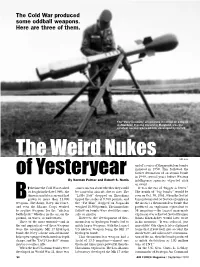

The Weird Nukes of Yesteryear

The Cold War produced some oddball weapons. Here are three of them. The “Davy Crockett,” shown here mounted on a tripod at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, was the smallest nuclear warhead ever developed by the US. The Weird Nukes DOD photo end of a series of thermonuclear bombs initiated in 1950. This followed the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb of Yesteryear in 1949, several years before Western By Norman Polmar and Robert S. Norris intelligence agencies expected such an event. y the time the Cold War reached some concern about whether they could It was the era of “bigger is better.” its height in the late 1960s, the be carried in aircraft, due to size. The The zenith of “big bombs” would be American nuclear arsenal had “Little Boy” dropped on Hiroshima seen on Oct. 30, 1961, when the Soviet grown to more than 31,000 tipped the scales at 9,700 pounds, and Union detonated (at Novaya Zemlya in Bweapons. The Army, Navy, Air Force, the “Fat Man” dropped on Nagasaki the Arctic) a thermonuclear bomb that and even the Marine Corps worked weighed 10,300 pounds. The immediate produced an explosion equivalent to to acquire weapons for the “nuclear follow-on bombs were about the same 58 megatons—the largest man-made battlefield,” whether in the air, on the size or smaller. explosion ever achieved. Soviet Premier ground, on water, or underwater. However, the development of ther- Nikita Khrushchev would later write Three of the more unusual—and in monuclear or hydrogen bombs led to in his memoirs: “It was colossal, just the end impractical—of these weapons much larger weapons, with the largest incredible! Our experts later explained were the enormous Mk 17 hydrogen US nuclear weapon being the Mk 17 to me that if you took into account the bomb, the Navy’s drone anti-submarine hydrogen bomb.