Submissions: Inquiry Into Plain Tobacco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 01 GSF Website Version and Format.Xlsx

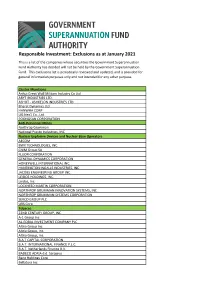

Responsible Investment: Exclusions as at January 2021 This is a list of the companies whose securities the Government Superannuation Fund Authority has decided will not be held by the Government Superannuation Fund. This exclusions list is periodically reviewed and updated, and is provided for general information purposes only and not intended for any other purpose. Cluster Munitions Anhui Great Wall Military Industry Co Ltd ARYT INDUSTRIES LTD. ASHOT ‐ ASHKELON INDUSTRIES LTD. Bharat Dynamics Ltd HANWHA CORP LIG Nex1 Co., Ltd. POONGSAN CORPORATION Anti‐Personnel Mines Northrop Grumman National Presto Industries, INC Nuclear Explosive Devices and Nuclear Base Operators AECOM BWX TECHNOLOGIES, INC. CNIM Group SA FLUOR CORPORATION GENERAL DYNAMICS CORPORATION HONEYWELL INTERNATIONAL INC. HUNTINGTON INGALLS INDUSTRIES, INC. JACOBS ENGINEERING GROUP INC. LEIDOS HOLDINGS, INC. Leidos, Inc. LOCKHEED MARTIN CORPORATION NORTHROP GRUMMAN INNOVATION SYSTEMS, INC. NORTHROP GRUMMAN SYSTEMS CORPORATION SERCO GROUP PLC URS Corp Tobacco 22ND CENTURY GROUP, INC. A‐1 Group Inc AL‐EQBAL INVESTMENT COMPANY PLC Altria Group Inc Altria Group, Inc. Altria Group, Inc. B.A.T CAPITAL CORPORATION B.A.T. INTERNATIONAL FINANCE P.L.C. B.A.T. Netherlands Finance B.V. BADECO ADRIA d.d. Sarajevo Bang Holdings Corp Bellatora Inc Tobacco continued Bots Inc BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO (MALAYSIA) BERHAD BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO BANGLADESH CO. LTD. British American Tobacco Holdings (The Netherlands) B.V. British American Tobacco Kenya plc BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO P.L.C. BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO P.L.C. British American Tobacco Uganda British American Tobacco Vranje a.d. Vranje British American Tobacco Zambia PLC British American Tobacco Zimbabwe (Holdings) Ltd Bulgartabac holding AD Carreras Ltd Cerealcom SA Alexandria CEYLON TOBACCO COMPANY PLC China Boton Group Company Limited Coka Duvanska Industrija ad Coka CONG TY CO PHAN NGAN SON CTO Public Company Ltd Duvanska industrija ad Bujanovac Eastern Company SAE ELECTRONIC CIGARETTES INTERNATIONAL GROUP, LTD. -

FY 2020 Announcement.Pdf

17 February 2021 –PRELIMINARY RESULTS BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO p.l.c. YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 ‘ACCELERATING TRANSFORMATION’ GROWTH IN NEW CATEGORIES AND GROUP EARNINGS DESPITE COVID-19 PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS REPORTED ADJUSTED Current Vs 2019 Current Vs 2019 rates Rates (constant) Cigarette and THP volume share +30 bps Cigarette and THP value share +20 bps Non-Combustibles consumers1 13.5m +3.0m Revenue (£m) £25,776m -0.4% £25,776m +3.3% Profit from operations (£m) £9,962m +10.5% £11,365m +4.8% Operating margin (%) +38.6% +380 bps +44.1% +100 bps2 Diluted EPS (pence) 278.9p +12.0% 331.7p +5.5% Net cash generated from operating activities (£m) £9,786m +8.8% Free cash flow after dividends (£m) £2,550m +32.7% Cash conversion (%)2 98.2% -160 bps 103.0% +650 bps Borrowings3 (£m) £43,968m -3.1% Adjusted Net Debt (£m) £39,451m -5.3% Dividend per share (pence) 215.6p +2.5% The use of non-GAAP measures, including adjusting items and constant currencies, are further discussed on pages 48 to 53, with reconciliations from the most comparable IFRS measure provided. Note – 1. Internal estimate. 2. Movement in adjusted operating margin and operating cash conversion are provided at current rates. 3. Borrowings includes lease liabilities. Delivering today Building A Better TomorrowTM • Revenue, profit from operations and earnings • 1 growth* absorbing estimated 2.5% COVID-19 revenue 13.5m consumers of our non-combustible products , headwind adding 3m in 2020. On track to 50m by 2030 • New Categories revenue up 15%*, accelerating • Combustible revenue -

Imperial-Ham-La:Layout 1

CMAJ Special report Destroyed documents: uncovering the science that Imperial Tobacco Canada sought to conceal David Hammond MSc PhD, Michael Chaiton MSc, Alex Lee BSc, Neil Collishaw MA Previously published at www.cmaj.ca Abstract provided a wealth of information about the conduct of the tobacco industry, the health effects of smoking and the role Background: In 1992, British American Tobacco had its of cigarette design in promoting addiction.2 Canadian affiliate, Imperial Tobacco Canada, destroy inter- A number of the most sensitive documents were concealed nal research documents that could expose the company to or destroyed before the trial as the threat of litigation grew.3,4 liability or embarrassment. Sixty of these destroyed docu- Based on advice from their lawyers, companies such as ments were subsequently uncovered in British American British American Tobacco instituted a policy of document Tobacco’s files. destruction.5 A.G. Thomas, the head of Group Security at Methods: Legal counsel for Imperial Tobacco Canada pro- British American Tobacco, explained the criteria for selecting vided a list of 60 destroyed documents to British American reports for destruction: “In determining whether a redundant Tobacco. Information in this list was used to search for document contains sensitive information, holders should copies of the documents in British American Tobacco files released through court disclosure. We reviewed and sum- apply the rule of thumb of whether the contents would harm marized this information. or embarrass the Company or an individual if they were to be made public.”6 Results: Imperial Tobacco destroyed documents that British American Tobacco’s destruction policy was most included evidence from scientific reviews prepared by rigorously pursued by its subsidiaries in the United States, British American Tobacco’s researchers, as well as 47 ori - gin al research studies, 35 of which examined the biological Canada and Australia, likely because of the imminent threat activity and carcinogenicity of tobacco smoke. -

On Appeal from the Court of Appeal for British Columbia

Court File No. 33563 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR BRITISH COLUMBIA) BETWEEN: THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA APPELLANT/RESPONDENT BY CROSS-APPEAL (THIRD PARTY) – and – IMPERIAL TOBACCO CANADA LIMITED, ROTHMANS, BENSON & HEDGES INC., ROTHMANS INC., JTI-MACDONALD CORP., B.A.T INDUSTRIES P.L.C., BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO (INVESTMENTS) LIMITED, CARRERAS ROTHMANS LIMITED, PHILIP MORRIS USA INC., PHILIP MORRIS INTERNATIONAL INC., R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY and R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO INTERNATIONAL, INC. RESPONDENTS/APPELLANTS BY CROSS-APPEAL (APPELLANTS) – and – HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA RESPONDENT (RESPONDENT) – and – ATTORNEY GENERAL OF BRITISH COLUMBIA and ATTORNEY GENERAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK INTERVENERS CONSOLIDATED FACTUM OF RESPONDENTS ON APPEAL AND CONSOLIDATED FACTUM OF APPELLANTS ON CROSS-APPEAL OF ROTHMANS, BENSON & HEDGES INC., ROTHMANS INC., PHILIP MORRIS USA INC. AND PHILIP MORRIS INTERNATIONAL INC. (pursuant to Rules 42 and 43 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada) COUNSEL FOR ROTHMANS, BENSON & OTTAWA AGENT FOR ROTHMANS, HEDGES INC. AND ROTHMANS INC. BENSON & HEDGES INC. AND MACAULAY McCOLL LLP ROTHMANS INC. 1575 – 650 West Georgia Street GOWLING LAFLEUR HENDERSON LLP Vancouver, British Columbia V6B 4N9 2600 – 160 Elgin Street Telephone: 604-687-9811 Ottawa, Ontario K1P 1C3 Facsimile: 604-687-8716 Telephone: 613-233-1781 KENNETH N. AFFLECK, Q.C. Facsimile: 613-563-9869 HENRY S. BROWN, Q.C. COUNSEL FOR PHILIP MORRIS USA OTTAWA AGENT FOR PHILIP MORRIS INC. USA INC. DAVIS & COMPANY LLP GOWLING LAFLEUR HENDERSON LLP 2800 – 666 Burrard Street 2600 – 160 Elgin Street Vancouver, British Columbia V7Y 1K2 Ottawa, Ontario K1P 1C3 Telephone: 604-687-9444 Telephone: 613-233-1781 Facsimile: 604-687-1612 Facsimile: 613-563-9869 D. -

Imperial Tobacco Canada Limited and Imperial Tobacco Company Limited

Court File No. CV-19-616077-00CL Imperial Tobacco Canada Limited and Imperial Tobacco Company Limited PRE-FILING REPORT OF THE PROPOSED MONITOR March 12, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL .....................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................1 BACKGROUND ..............................................................................................................................6 FORUM .........................................................................................................................................14 ACCOMMODATION AGREEMENT ................................................................................................15 THE TOBACCO CLAIMANT REPRESENTATIVE .............................................................................17 IMPERIAL’S CASH FLOW FORECAST ..........................................................................................18 COURT-ORDERED CHARGES .......................................................................................................20 CHAPTER 15 PROCEEDINGS ........................................................................................................23 RELIEF SOUGHT ...........................................................................................................................24 CONCLUSION ...............................................................................................................................25 -

Ceylon Tobacco Company Plc Annual Report 2020

The Next CEYLON TOBACCO COMPANY PLC Step ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Contents Overview Our ESG Performance Financial Statements 2 CTC at a Glance 54 Environment 100 Finance Director’s Review 3 The Year in Numbers 59 Social 102 Financial Reporting Calendar 4 About the Report 64 Governance 103 Independent Auditor's Report 6 Our New Corporate Logo 105 Statement of Profit or Loss and other Our Leadership 7 Our Response to COVID-19 Comprehensive Income 68 Board of Directors 8 Performance Highlights 106 Statement of Financial Position 72 Executive Committee 107 Statement of Changes in Equity Executive Review and 108 Statement of Cash Flows Strategic Positioning Governance and Risk 109 Notes to the Financial Statements 10 Chairman’s Review 76 Board Governance 143 Statement of Value Added 14 Managing Director & CEO’s Review 77 Driving Strategy and Performance 18 Value Creation Model 80 Compliance Overview Supplementary Information 82 Corporate Governance 20 Value Creation and Trade-offs 144 Share Information 85 Risk Management 22 Strategy for Accelerated Growth 148 Notes 88 Assessment of Going Concern 24 Industry Overview 151 Notice of Meeting 89 Statement of Internal Controls 25 Our Sustainability Agenda 152 AGM 2021 Instructions to Shareholders 90 Report of the Board of Directors 26 Stakeholder Value 153 Form of Proxy 93 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 28 Material Matters 155 Appendices for Financial Statements IBC Corporate Information Performance and Value Creation 94 Report of the Audit Committee 30 Delivering our Strategy 96 Report of the Related Party Transactions 30 Illicit Trade and Beedi Review Committee 32 Product Responsibility 97 Report of the Board Compensation and 34 Optimising the Manufacturing Footprint Remuneration Committee 36 Leveraging Our Brands 98 Report of the Nominations Committee 38 Our Product SKUs 40 Sustainable Supply Chain 43 Strength in Distribution 45 Managing People 50 Ensuring a Safe Working Environment Online references: http://www.ceylontobaccocompany.com Scan the QR Code with your smart device to view this report online. -

Ceylon Tobacco Company Plc Annual Report 2016 an Overview of Our Business

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 CEYLON TOBACCO COMPANY PLC ABOUT THIS REPORT Ceylon Tobacco Company PLC (CTC) and material issues that may potentially Sri Lanka and the Securities and Exchange first embraced the principles of Integrated have an impact on our ability to create Commission of Sri Lanka and the GRI Reporting in 2015, and this year we hope value. The material issues included herein G4 Guidelines. The financial information to build on the foundation put in place were selected through a structured and presented herein is in compliance with the last year to clearly and comprehensively comprehensive process as detailed on Sri Lanka Financial Reporting Standards, articulate our commitment to creating value pages 64 and 65 of this Report. For and external assurance on the same for all our stakeholders. As our primary sustainability reporting, we have adopted has been provided by Messers KPMG report to stakeholders, this Integrated the criteria prescribed by the Global (Chartered Accountants). Annual Report demonstrates the Company’s Reporting Initiative (GRI) G4 Framework, commitment to developing and directing building on the previous report for the year REPORTING ENHANCEMENTS strategy in a manner that balances the ending 31 December 2015. We understand that Integrated Reporting competing interests of our stakeholders and is a continuously evolving journey, and this provides details on emerging risks and REPORTING PRINCIPLES AND year we have sought to further improve opportunities, successes and challenges ASSURANCE the meaningfulness and readability of our in delivering value and our strategies and This report has been prepared based Report through, targets going forward. on the guidelines of the Integrated Reporting (IR) Framework published by • Enhanced connectivity of information SCOPE AND BOUNDARY the International Integrated Reporting through linking the narrative to our The Company’s Integrated Report is Council. -

Stop Smoking Systems BOOK

Stop Smoking Systems A Division of Bridge2Life Consultants BOOK ONE Written by Debi D. Hall |2006 IMPORTANT REMINDER – PLEASE READ FIRST Stop Smoking Systems is Not a Substitute for Medical Advice: STOP SMOKING SYSTEMS IS NOT DESIGNED TO, AND DOES NOT, PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE. All content, including text, graphics, images, and information, available on or through this Web site (“Content”) are for general informational purposes only. The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. NEVER DISREGARD PROFESSIONAL MEDICAL ADVICE, OR DELAY IN SEEKING IT, BECAUSE OF SOMETHING YOU HAVE READ IN THIS PROGRAMMATERIAL. NEVER RELY ON INFORMATION CONTAINED IN ANY OF THESE BOOKS OR ANY EXERCISES IN THE WORKBOOK IN PLACE OF SEEKING PROFESSIONAL MEDICAL ADVICE. Computer Support Services Not Liable: IS NOT RESPONSIBLE OR LIABLE FOR ANY ADVICE, COURSE OF TREATMENT, DIAGNOSIS OR ANY OTHER INFORMATION, SERVICES OR PRODUCTS THAT YOU OBTAIN THROUGH THIS SITE. Confirm Information with Other Sources and Your Doctor: You are encouraged to confer with your doctor with regard to information contained on or through this information system. After reading articles or other Content from these books, you are encouraged to review the information carefully with your professional healthcare provider. Call Your Doctor or 911 in Case of Emergency: If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor or 911 immediately. DO NOT USE THIS READING MATERIAL OR THE SYSTEM FOR SMOKING CESSATION CONTAINED HEREIN FOR MEDICAL EMERGENCIES. No Endorsements: Stop Smoking Systems does not recommend or endorse any specific tests, products, procedures, opinions, physicians, clinics, or other information that may be mentioned or referenced in this material. -

Mercer Survey Panel

MERCER SURVEY PANEL 2013 PAY FOR PERFORMANCE SURVEY NOV 2013 INTRODUCTION Organizations continue to struggle with their pay for performance approaches. New economic realities, reduced pay increase budgets and incentive pools, shareholder activism, and emerging government regulations make well- managed pay for performance increasingly critical, but ever-more difficult to achieve. For questions, additional Frequently, HR and Rewards leaders ask us for best practices in the design and information or feedback implementation of pay for performance. If we or anyone chose to answer that on the survey results, query by relying on prevalence alone, a person would be left to believe there is please contact: one basic model of pay for performance that constitutes best practice – namely an approach that relies on increasingly differentiated financial Customer Service: 800 333 3070 incentives where year-to-year base pay increases and annual incentive payouts Email: [email protected] are strictly aligned to individual performance. To learn more about Mercer products and services, please visit imercer.com Jeanie Adkins, Partner +1 502 561 8944 [email protected] The information and data contained in this report are for information purposes only and are not intended nor implied to be a substitute for professional advice. In no event will Mercer be liable to Brian Levine, Partner you or to any third party for any decision made or action taken in reliance of the results obtained through the use of the information and/or data contained or provided herein. +1 212 345 4194 [email protected] ©2013 Mercer LLC. All rights reserved. Survey materials and the data contained therein are copyrighted works owned exclusively by Mercer and may not be copied, modified, sold, transformed into any other media, or otherwise transferred in whole or in any part to any party other than the Haig Nalbantian, Sr. -

Packaging and Printed Paper Stewardship Plan

Packaging and Printed Paper Stewardship Plan November 19, 2012 Updated February 25, 2013 Updated April 8, 2013 Updated November 28, 2016 230-171 Esplanade West, North Vancouver, BC V7M 3J9 www.multimaterialbc.ca Packaging and Printed Paper Stewardship Plan Table of Contents................................................................................................................i 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 2. The Stewardship Agency .............................................................................................1 3. Packaging and Printed Paper ......................................................................................2 3.1 Packaging...............................................................................................................2 3.2 Printed Paper .........................................................................................................3 3.3 Sources of Packaging and Printed Paper ..............................................................3 4. Program Design ............................................................................................................4 4.1 BC Packaging and Printed Paper Reverse Supply Chain ......................................4 4.2 Packaging and Printed Paper Program Delivery Principles ...................................5 4.3 Packaging and Printed Paper Program Delivery Overview ....................................6 4.4 Collection of Packaging -

PTC Annual Report 2018

Celebrating Diversity And Inclusion Soaring through the decades, Pakistan Tobacco Company Limited has achieved uncountable successes. Throughout this journey, our focus has been to make the organisation more Diverse & Inclusive. By doing this, we have been able to create an environment that includes individuals of different ages, genders, backgrounds, cultures and beliefs making them a part of this big PTC family. 1 Table of Contents 04 12 26 42 68 80 Our Vision Our Partnerships Organisational Committees of the Operational Horizontal & Structure Board Excellence Vertical Analysis 04 16 28 44 70 82 Our Mission Our Guiding Position of Report of Audit Corporate Social Analysis of Principles Reporting Committee Responsibility Statement of Profit Organisation within or Loss & Statement Value Chain of Financial Position 05 18 30 46 72 84 Our Guiding Our Initiatives Strategic Objectives Standards of Calendar of Notable Summary of Principles Business Conduct & Events 2018 Statement of Profit Ethical Principles or Loss, Financial Position & Cash flows 06 20 32 53 73 85 British American Our Achievements Risk & Opportunity Chairman’s Review 2018 Performance Dupont Analysis Tobacco (BAT) Report 2018 07 22 36 55 74 86 BAT’s Geographical Our Exported Talent Illicit trade: Threat MD/CEO’s Message Critical Performance Liquidity, Cash Flows Spread to legitimate Indicators and Capital Structure industry’s sustainability 08 24 37 56 76 88 Pakistan Tobacco Our People Our Corporate Director’s Report Quarterly Analysis Performance Company Limited Pride Information -

Download Full Curriculum Vitae

Pollay CV (Feb 2013)...1 of 45 Sauder School of Business THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA 2053 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 CURRICULUM VITAE (as of February 2013) RICHARD W. POLLAY Home Address Professor Emeritus, Marketing Division 4506 West 8th Avenue Curator, History of Advertising Archives Vancouver, BC V6R 2A5 (604) 224-7322 Office Phone: (604) 822-8338 e-mail: [email protected] I. BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Place of Birth: New Britain, CT (USA) Sex: Male Date of Birth: June 28, 1940 Marital Status: Married Citizenship: Canadian & US Children: None II. EDUCATION a) Undergraduate 1958-1962: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, B. Management Engineering b) Graduate 1962-1963: University of Chicago, Masters of Business Administration 1964-1966: University of Chicago, Ph.D. (awarded, 1970) c) Graduate Theses Titles Ph.D.: "A Theoretical and Experimental Investigation into the Factors Affecting Decision Completion Time" d) Academic Awards Prior to Final Degree Ford Foundation Research Fellowship, Summer 1968 Sears and Roebuck Doctoral Fellowship, 1965 American Marketing Association, Certificate of Merit, 1962 Degree cum laude, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1962 Tau Beta Pi (Engineering Honorary) Epsilon Delta Sigma (Business Honorary) III. PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT RECORD a) Teaching or Research Positions Held Prior to UBC Appointment 1966-1970: Assistant Professor, University of Kansas b) Date of First UBC Appointment: July 1, 1970 Pollay CV (Feb 2013)...2 of 45 c) Rank of First Appointment: Associate Professor d) Subsequent Ranks